Prostate-Specific Antigen Testing in Ontario: Reasons for Testing Patients Without Diagnosed Prostate Cancer Education Éducation Peter S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

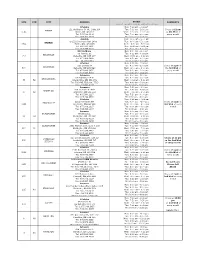

P.H.P. (Physician Health Program) Collection Site List.Xlsx

SITE STN CITY ADDRESS HOURS COMMENTS (hours of operation may be subject to change) LifeLabs Mon: 7:00 am - 2:00 pm 121 Wellington St. W., Suite 106 Tue: 7:00 am - 2:00 pm Closes at 12 pm BARRIE 1013 Barrie, ON L4N 1L2 Wed: 7:00 am - 11:00 am on 4th Wed of Tel: 705.728.1109 Thu: 7:00 am - 2:00 pm every month Fax: 705.728.4609 Fri: 7:00 am - 2:00 pm Acculab Mon: 9:00 am - 5:00 pm D-122 Commerce Park Drive Tue: 9:00 am - 5:00 pm BARRIE 3854 Barrie, ON, L4N 8W8 Wed: 9:00 am - 5:00 pm Tel: 866.991.1461 Thu: 9:00 am - 5:00 pm Fax: 705.999.8228 Fri: 9:00 am - 5:00 pm KAT Holdings Mon: 8:30 am - 4:00 pm 80 Harriett St. Tue: 8:30 am - 4:00 pm BELLEVILLE 757 Belleville, ON K8P 1V7 Wed: 8:30 am - 4:00 pm Tel: 613.966.9456 Thu: 8:30 am - 4:00 pm Fax: 613.967.9873 Fri: 8:30 am - 4:00 pm LifeLabs Mon: 9:00 am - 2:00 pm 210 Dundas St Tue: 9:00 am - 2:00 pm Closes at 2 pm on BELLEVILLE 690 Belleville, ON K8N 5G8 Wed: 9:00 am - 2:00 pm the 3rd Wed of Tel: 877.849.3637 Thu: 9:00 am - 2:00 pm every month Fax: 613.966.6068 Fri: 9:00 am - 2:00 pm Dynacare Mon: 8:00 am - 5:00 pm 55 Highway 118 W Tue: 8:00 am - 5:00 pm BRACEBRIDGE 36 52 Bracebridge, ON P1L 1T2 Wed: 8:00 am - 5:00 pm Tel: 705.645.7502 ext. -

Quantitative Analysis of Adalimumab (Humira®) and Anti-Adalimumab Antibodies (LS-163)

Quantitative Analysis of Adalimumab (Humira®) and Anti-Adalimumab Antibodies (LS-163) PRESCRIBER INFORMATION PATIENT INFORMATION Last Name: Last Name: First Name: First Name: Clinic: Sex: F M Address: Date of Birth: yyyy / mm / dd No Street Office Reference Number: City Prov. Postal code Tel: Health Insurance No.: (RAMQ, OHIP, etc.) Fax: Licence No. yyyy/mm/dd Signature: X Date SAMPLE COLLECTION TYPE OF SPECIMEN Serum: 1 mL DATE: ________/________/________ For optimal results, sample collection should be within 24-48 hours prior to the next Humira injection. Year Month Day RESULTS TRANSMISSION Results will be provided within 10 to 15 working days. Please note that the prescriber can elect to access patient results online. To request web access, please contact our customer service department. GD Specialized Diagnostics 3885 Industriel Blvd., Laval, Quebec, H7L 4S3 Tel: (450) 901-3071 / 1-888-988-1888 • Fax: (450) 663-4428 E-mail: [email protected] • Website: www.gamma-dynacare.com FOR INTERNAL USE ONLY Comments: __________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________ This analysis is supported by an unrestricted grant provided by Abbvie. Rev. 2014SE30 PATIENT INSTRUCTIONS ONTARIO / QUEBEC For sample collecon, please go to the nearest Gamma‐Dynacare Paent Services Centre (no appointment required). For a list of locaons and hours, go to www.gamma‐dynacare.com or call 1‐888‐988‐1888. MANITOBA For sample collecon, please call (204) 944‐0757 ext. 7253 to make an appointment at the following Gamma‐Dynacare Paent Services Centre: 830 King Edward St., #100, Winnipeg, MB, R3H 0P4. SASKATCHEWAN For sample collecon, please go to one of the following Gamma‐Dynacare Paent Services Centres, from Monday to Friday (no appointment required): Saskatoon – 39‐23rd St East, #5, Saskatoon, SK S7K 0H6, tel: (306) 655‐4030 Regina – 2723 Avonhurst Dr, Regina, SK S4R 3J3, tel: (306) 766‐6977 ALBERTA Sample collecon centres are located throughout the province. -

Gamma-Dynacare Medical Laboratories Is Aware of The

GAMMA-DYNACARE MEDICAL LABORATORIES PRIVACY POLICY Gamma-Dynacare Medical Laboratories is aware of the importance of protecting your privacy and we are sensitive to handling your personal information, in particular, your personal health information, appropriately. We are committed to collecting, using and disclosing your personal information responsibly and only as required to provide our services. We remain responsible and accountable to you for the personal information we collect and hold. To this end, we have developed this Privacy Policy, trained our professional, technical and support staff about our policies and practices and we have also appointed a Chief Privacy Officer and Regional Privacy Officers to ensure our Privacy Policy is complied with throughout our entire company. Should you have any questions or require additional information about our Privacy Policy, please email us at [email protected]. 1. Personal Information Personal information is any information that identifies you, or by which your identity could be deduced and includes any health related information. Business information however (for example, your business title or business address and business telephone number) is not considered to be personal information according to privacy legislation. Generally speaking, if we do not collect and use your personal information, we cannot provide you with our services. 2. Purposes for the Collection, Use and Disclosure of Personal Information We will only collect that information necessary for the purposes -

Health & Life Sciences

SECTOR PROFILE HEALTH & LIFE SCIENCES BIOTECHNOLOGY FIRMS 100 WITHIN A 30 MINUTE DRIVE HIGHLY SKILLED TALENT: ACCESS TO 4.3 MILLION LABOUR POOL ACROSS THE GREATER TORONTO AREA LOCATED IN THE MIDDLE OF CANADA’S INNOVATION ND We are very excited to CORRIDOR, ACCESS TO occupy this leading-edge OVER 20K TECH COMPANIES campus in Brampton. It’s an AND 30% OF CANADA’S 2FASTEST UNIVERSITY GRADUATES GROWING CITY investment for our IN CANADA WITH Canadian employees, 14,000 our customers and TRANSCONTINENTAL HIGHWAYS NEW RESIDENTS the infrastructure ACCESSING 158M CONSUMERS PER YEAR equired for our rapid growth in Canada. We are very happy to have found such LEADING EDGE OF CYBERSECURITY, a great location. HOME TO THE ROGERS CYBERSECURE CATALYST Neil Fraser President Medtronic of Canada Ltd. YOUNG, DIVERSE 9TH LARGEST CITY ADJACENT TO WORKFORCE WITH IN CANADA WITH A CANADA’S LARGEST 234 CULTURES SPEAKING POPULATION CLOSE INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT 115 LANGUAGES TO 700,000 TORONTO PEARSON MARTIN BOHL Sector Manager, Health & Life Sciences 905.874.5936 | [email protected] BRAMPTON, Part of the Greater Toronto Area SECTOR PROFILE HEALTH & LIFE SCIENCES Brampton is Located in North America’s 3rd Largest Biotechnology Cluster TOP LOCATION 40% OF CANADA’S LIFE FOR PHARMA SCIENCES COMPANIES PRODUCTION AND ARE LOCATED IN THE BIOTECHNOLOGY GREATER TORONTO AREA AND R&D • 22,500 people working in the Life Sciences sector in Ontario at more than 1,300 companies that collectively earn $12.2 billion in revenues annually, with exports totalling $1.45 billion. Talent • Brampton is part of this Ontario ecosystem and offers access to a community research • Education in life science-related hospital, clinical trials with a diverse population, a supportive local government, and programs has tripled since 2006 within access to youth and talent. -

Volume 25, Issue 31, Aug 02, 2002

The Ontario Securities Commission OSC Bulletin August 2, 2002 Volume 25, Issue 31 (2002), 25 OSCB The Ontario Securities Commission Administers the Securities Act of Ontario (R.S.O. 1990, c.S.5) and the Commodity Futures Act of Ontario (R.S.O. 1990, c.C.20) The Ontario Securities Commission Published under the authority of the Commission by: Cadillac Fairview Tower Carswell Suite 1903, Box 55 One Corporate Plaza 20 Queen Street West 2075 Kennedy Road Toronto, Ontario Toronto, Ontario M5H 3S8 M1T 3V4 416-593-8314 or Toll Free 1-877-785-1555 416-609-3800 or 1-800-387-5164 Contact Centre - Inquiries, Complaints: Fax: 416-593-8122 Capital Markets Branch: Fax: 416-593-3651 - Registration: Fax: 416-593-8283 - Filings Team 1: Fax: 416-593-8244 - Filings Team 2: Fax: 416-593-3683 - Continuous Disclosure: Fax: 416-593-8252 - Insider Reporting Fax: 416-593-3666 - Take-Over Bids / Advisory Services: Fax: 416-593-8177 Enforcement Branch: Fax: 416-593-8321 Executive Offices: Fax: 416-593-8241 General Counsel=s Office: Fax: 416-593-3681 Office of the Secretary: Fax: 416-593-2318 The OSC Bulletin is published weekly by Carswell, under the authority of the Ontario Securities Commission. Subscriptions are available from Carswell at the price of $549 per year. Subscription prices include first class postage to Canadian addresses. Outside Canada, these airmail postage charges apply on a current subscription: U.S. $175 Outside North America $400 Single issues of the printed Bulletin are available at $20.00 per copy as long as supplies are available. -

Neighborhood Walkability and Pre-Diabetes Incidence in a Multiethnic Population

Epidemiology/Health Services Research BMJ Open Diab Res Care: first published as 10.1136/bmjdrc-2019-000908 on 29 June 2020. Downloaded from Open access Original research Neighborhood walkability and pre- diabetes incidence in a multiethnic population Ghazal S Fazli ,1,2 Rahim Moineddin,3 Anna Chu,4 Arlene S Bierman,2 Gillian L Booth1,2,4,5 To cite: Fazli GS, ABSTRACT Moineddin R, Chu A, et al. Introduction We examined whether adults living in highly Significance of this study Neighborhood walkability walkable areas are less likely to develop pre-diabetes and and pre- diabetes incidence if so, whether this association is consistent according to What is already known about this subject? in a multiethnic population. immigration status and ethnicity. ► Growing evidence has shown that adults living in BMJ Open Diab Res Care Research design and methods Population- level health, neighborhoods that are highly walkable achieve 2020;8:e000908. doi:10.1136/ higher mean step counts per day and are more like- bmjdrc-2019-000908 immigration, and administrative databases were used to identify adults aged 20–64 (n=1 128 181) who had ly to meet recommended levels of physical activity normoglycemia between January 2011 and December than residents in less walkable areas. ► Additional material is 2011 and lived in one of 15 cities in Southern Ontario, ► However, because of residential self- selection, it is published online only. To view Canada. Individuals were assigned to one of ten deciles unclear if individuals living in more walkable neigh- please visit the journal online (D) of neighborhood walkability (from lowest (D1) to borhoods are healthier to begin with, resulting in (http:// dx. -

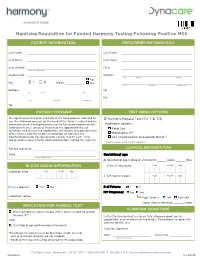

Manitoba Requisition for Funded Harmony Testing Following Positive MSS

Manitoba Requisition for Funded Harmony Testing Following Positive MSS PATIENT INFORMATION PRESCRIBER INFORMATION Last Name Last Name First Name First Name Date of Birth Clinic Year / Month / Day Health Ins. No. Address No Street Office ☐ kg Sex ☒ F ☐ M Weigh ☐ lbs City Province Postal code Address Tel No Street Apt. Fax City Province Postal code Tel PATIENT CONSENT TEST MENU OPTIONS My signature on this form indicates that I have read, or had read to ☒ Harmony Prenatal Test (T21, T18, T13) me, the informed consent on the back of this form. I understand the informed consent and give permission to Dynacare to provide the Additional options: laboratory test(s) selected. I have had the opportunity to ask ☐ Fetal Sex questions and discuss the capabilities, limitations, and possible risks 1,2 of the test(s) with my healthcare provider or someone my ☐ Monosomy X healthcare provider has designated. I know that if I wish, I may ☐ Sex Chromosome Aneuploidy Panel1,2 obtain professional genetic counselling before signing this consent. 1Singletons only. 2Fetal sex not reported. Patient Signature CLINICAL INFORMATION Date Gestational age Year / Month / Day A Gestational age at date of ultrasound: ______ weeks ______ days BLOOD DRAW INFORMATION Date of ultrasound: Year Month Day Collection Date Year Month Day B IVF Transfer Date Year Month Day Is this a redraw? ☐ Yes ☐ No # of Fetuses ☐ 1 ☐ 2 IVF Pregnancy ☐ No ☐ Yes Collection Centre Egg Donor is: ☐ Self ☐ Non-self Donor Age at Retrieval: _______ years INDICATION FOR FUNDED TEST* CLINICIAN SIGNATURE ☐ Positive Maternal Serum Screen (MSS) Down syndrome and/or trisomy 18** I attest that my patient has been fully informed about details, AND capabilities, and limitations of the test(s). -

Corporate Presentation January 2020

Corporate Presentation January 2020 Investor Relations Contact [email protected] 1-833-680-4948 Disclaimer This presentation, and any supplements and amendments to this presentation, has been prepared by Fire & Flower Holdings Corp. (“Fire & Flower” or the “Company”). This presentation is for informational purposes only and not, and shall under no circumstances be construed as, an offer to buy, sell issue or subscribe for, the solicitation of an offer to buy, sell or subscribe for, or an advertisement or a public offering in any jurisdiction of, the securities referred to in this presentation. When used herein, references to ”Fire & Flower” or the “Company” refer to Fire & Flower Holdings Corp. and each of its subsidiaries as the context requires. No securities commission or similar authority in Canada has reviewed or in any way passed upon this presentation or the merits of the securities described herein and any representation to the contrary is an offence. The information contained in this presentation is subject to change without notice and is based on publicly available information, internally developed data and other sources. Where any opinion or belief is expressed in this presentation, it is based on the assumptions and limitations mentioned herein and is an expression of present opinion or belief only. No warranties or representations can be made as to the origin, validity, accuracy, completeness, currency or reliability of the information. Fire & Flower expressly disclaims and excludes all liability (to the maximum extent permitted by law), for losses, claims, damages, demands, costs and expenses of whatever nature arising in any way out of or in connection with the information in this presentation, its accuracy, completeness or by reason of reliance by any person on any of it. -

Gamma-Dynacare Medical Laboratories

We are proud to be one of Greater Toronto’s Top Employers for sixth year in a row! We are currently recruiting for Clinical Laboratory Assistants and Medical Laboratory Technologists to join our Chemistry, Hematology, Histology and Microbiology teams in Brampton. These highly skilled individuals should have one (1) year Chemistry, Hematology, Histology or Microbiology experience, be in good standing with the CMLTO and registered with the CSMLS. A number of positions are also available for Laboratory Assistant positions within our Patient Service Centers. Gamma-Dynacare is one of Canada's largest and most respected providers of laboratory services and health care solutions, with more than 50 years of experience serving Canadians. Headquartered in Brampton, Ontario, Gamma-Dynacare operates laboratories in Ontario (Brampton, Bowmanville, London, Ottawa and Thunder Bay), Quebec (Saint-Laurent and Laval), Manitoba (Winnipeg) and Alberta (Edmonton). Its operations also include more than 200 Patient Services Centres in Ontario, Manitoba and Saskatchewan. Gamma-Dynacare also provides medical information collection services for the insurance industry under the name MedAxio, and medical courier and logistics services under the name Accuro Health Services. Gamma-Dynacare's 2,400 skilled and dedicated employees perform 50 million tests each year, supporting patients, healthcare professionals and public and private sector clients with the laboratory services and critical information necessary for good health care and health-related decisions We are a great place to work! We offer competitive pay and great benefits along with a challenging and fun atmosphere. This is your opportunity to have a meaningful career that impacts lives, every day. “Caring for People” is what we do. -

Gamma-Dynacare Medical Laboratories Ontario Patient Services Centres

GAMMA-DYNACARE MEDICAL LABORATORIES ONTARIO PATIENT SERVICES CENTRES As one of the largest providers of licensed medical diagnostic services in Canada, Gamma-Dynacare has built a wide network of specimen collection Patient Services Centres across Ontario and beyond. Their convenient locations have made them attractive to the pharmaceutical industry for sample collection for clinical trials. Our knowledgeable staff will draw, prepare, package and ship specimens to our laboratories as well as to others across North America. Most visits to our Patient Services Centres, do not require appointments; however, Glucose, Lactose and Xylose Tolerance Tests, Holter Monitoring, Helicobacter Pylori, Breath Alcohol Testing and DOT urines procedures will require appointments. For Semen Analysis please refer to the Collection Instruction Section of this manual for further information. To inquire about our hours of operation, please call the Customer Service Department nearest to you. SERVICES AVAILABLE Breath Alcohol Testing UREA Breath Test for Helicobacter Pylori Department of Transportation (DOT) Urines, Pre-employment drug testing and observed collections E.C.G. Holter Monitor Methadone Programs and Drugs of Abuse Monitoring Pulmonary Function STAT Laboratory Patient Education Programs Paternity Testing Clinical Trial Collections Viral Load Testing Collections for Occupational Health Testing Finger printing A Breath Alcohol Testing H Holter Monitor O Saliva B Urea Breath Test For H. Pylori I Semen Analysis – Post Vasectomy P Pulmonary Function C -

HSN Presentation to NEACC

Presentation to NEACC June 11 2015 WhatWhat is isNew New & &Exciting Exciting at at HSN HSN NEON • OLIS & OLIS Viewer cNEO • Background • HSN and the Region’s Roles • Next Steps What is OLIS OLIS -> Ontario Laboratories Information System Facilitates the secure, electronic exchange of laboratory tests orders and results (current and historical). Is a province-wide repository of lab data that is comprised of hospitals, community laboratories, public health laboratories and practitioners and enables the sharing of lab data across the province. OLIS OVERVIEW Laboratory Future (Haematology, • Manage Referrals to Chemistry, Microbiology, performing laboratories Solution to view results Blood Bank and • Support Physician Office from the OLIS repository Pathology) data into the Integration for laboratory provincial OLIS test ordering and results repository Data OLIS DC to Date(DC) Area Associated hospitals Test Volume LHIN 13 – North Anson General, Bingham Memorial, Blind River, 2.07% East Ontario Chapleau, Engelhart & District, Espanola General, Haem Network (NEON) & Hornpayne, Kickland & District, Lady Dunn, Lady Chem West Parry Sound Minto, Manitoulin, Mattawa General, Notre-Dame, Micro Sensenbrenner, Smooth Rock Falls, St. Joseph’s BBK General, HSN, Temiskaming, Timmins & District, West Path Nipissing General , West Parry Sound Health LHIN 13 – Non- North Bay Health Center, Sault Area Hospital, 0.84% NEON sites LHIN 14 – North Dryden Regional Health Centre, Geraldton District 1.10% West Health Hospital, Manitouwadge Hospital, Nipigon District -

Geosoft Inc Automates Talent Management with Emperform

Gamma-Dynacare Medical Laboratories Modernizes Its Talent Management Processes by Going Online with emPerform Overview Gamma-Dynacare's more than 2,000 skilled and dedicated employees perform millions of tests each year, supporting patients, healthcare Gamma-Dynacare Medical Laboratories professionals and public and private sector clients with the laboratory needed to modernize its talent manage- services and critical information necessary for good health care and ment processes in order to consolidate health-related decisions. reviews and better track the performance of managers and employees. Their new Challenges online solution has allowed this top Canadian organization to: Gamma-Dynacare had no formal process in place for assessing and • Gain consistency with their review monitoring the performance of its workforce of over 2,000 highly skilled process so employees are evaluated professionals. They began to design a formal talent management accurately and fairly program from the ground up that would help them to address their • Centralize all performance data and metrics for senior management unique challenges. and HR • Better track the progress of Shortage of Available Talent: Like many other specialized organiza- employee goals to ensure everyone knows exactly what is expected of tions, Gamma-Dynacare has difficulties finding the highly-skilled and them specialized talent needed. There is a shortage in the labor market and as • Greatly improve how performance a result, recruiting people with the required skill set is very challenging data is collected and used in and can be very expensive. Gamma-Dynacare knew it had to make an reviews investment to develop high-performing individuals so that they would • Identify and develop highly-skilled employees to fill vacancies be able to fill the current and impending vacancies.