Historic Shipwrecks Discovered in International Waters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021 Camp Spotlights

Pirate Adventures July 12-16, 2021 1:00-4:30 PM, $49 per day Make it a full day for $98 by adding a morning camp! Arrr-matey! It’s out to sea we go! Attention all scalliwags and explorers: Are your kids interested in sailing the seven seas, swinging on a rope, dropping into the sea, and building their own pirate ship? The life of a pirate is not for the couch-potato - get up and be active this summer at Airborne! Every day is a new adventure, and a new pirate joke of course! Monday: What does it take to be a Pirate? Campers will pick out their very own pirate name, and add their name to the crew list. Now that the campers are official Pirates, it’s time for them to explore some of the physical tasks pirates have to do. Using the different equipment like the ropes, trampoline, bars, ladders and balance beams we will learn how to climb, jump, swing and balance (for sword fighting) like a pirate. Each camper will get a turn to complete the Pirate Agility Obstacle Course, that includes each of these tasks, to earn gold coins. Tuesday: Battle at Sea! Pirates face so many challenges… can you get around with only one leg? Can you walk the plank without falling in? Can you defend your ship and sink the other ships in return? Can you earn your golden treasure? Come and sail the friendly seas, if you dare! Arrr! Wednesday: Building a Pirate Ship! Campers will learn about all the different parts of a pirate ship and then work as a crew and build their very own ship. -

Treasure Island Int.Indd 3 4/12/10 9:12 AM Inspectionfor Teachers'

inspectionFor teachers' ONLY | Contents | 1 The End of Billy Bones .......................................5 2 Flint’s Treasure Map .........................................12 3 Long John Silver ...............................................19 4 On Treasure Island ............................................27 5 Defending the Stockade ....................................35 6 Clashing Cutlasses ............................................42 7 Jim on His Own ................................................50 8 Pieces of Eight! .................................................57 9 The Treasure Hunt .............................................64 10 Ben Gunn’s Secret .............................................73 Activities ...........................................................81 Treasure Island_int.indd 3 4/12/10 9:12 AM inspectionFor teachers' | 1 | ONLY The End of Billy Bones Squire Trelawney and some of the other gentlemen have asked me to write down the story of Treasure Island. I, Jim Hawkins, gave them my promise to do so. So I will tell you everything that happened—from beginning to end. I will leave out nothing except the location of the island—for there is still treasure there. I go back in time to the 1700’s. This is when my father still ran the Admiral Benbow Inn. And this is the same year the old sailor came into the inn, carrying a battered old sea chest. He was a tall, rough-looking man, brown as a nut. His hands were scarred. Across one cheek was a jagged old scar from the slash of a sword. “Do many people come this way?” he asked. 5 Treasure Island_int.indd 5 4/12/10 9:12 AM Treasure IslaNd inspectionFor teachers' My father said, “No, very few.” That was true. We lived on a lonely stretchONLY of the English coast. Few travelers came our way. One day, the old seaman took me aside. -

Gibraltar Harbour Bernard Bonfiglio Meng Ceng MICE 1, Doug Cresswell Msc2, Dr Darren Fa Phd3, Dr Geraldine Finlayson Phd3, Christopher Tovell Ieng MICE4

Bernard Bonfiglio, Doug Cresswell, Dr Darren Fa, Dr Geraldine Finlayson, Christopher Tovell Gibraltar Harbour Bernard Bonfiglio MEng CEng MICE 1, Doug Cresswell MSc2, Dr Darren Fa PhD3, Dr Geraldine Finlayson PhD3, Christopher Tovell IEng MICE4 1 CASE Consultants Civil and Structural Engineers, Torquay, United Kingdom, 2 HR Wallingford, Howbery Park, Wallingford, Oxfordshire OX10 8BA, UK 3 Gibraltar Museum, Gibraltar 4 Ramboll (Gibraltar) Ltd, Gibraltar Presented at the ICE Coasts, Marine Structures and Breakwaters conference, Edinburgh, September 2013 Introduction The Port of Gibraltar lies on a narrow five kilometer long peninsula on Spain’s south eastern Mediterranean coast. Gibraltar became British in 1704 and is a self-governing territory of the United Kingdom which covers 6.5 square kilometers, including the port and harbour. It is believed that Gibraltar has been used as a harbour by seafarers for thousands of years with evidence dating back at least three millennia to Phoenician times; however up until the late 19th Century it provided little shelter for vessels. Refer to Figure 1 which shows the coast line along the western side of Gibraltar with the first structure known as the ‘Old Mole’ on the northern end of the town. Refer to figure 1 below. Location of the ‘Old Mole’ N The Old Mole as 1770 Figure 1 Showing the harbour with the first harbour structure, the ‘Old Mole’ and the structure in detail as in 1770. The Old Mole image has been kindly reproduced with permission from the Gibraltar Museum. HRPP577 1 Bernard Bonfiglio, Doug Cresswell, Dr Darren Fa, Dr Geraldine Finlayson, Christopher Tovell The modern Port of Gibraltar occupies a uniquely important strategic location, demonstrated by the many naval battles fought at and for the peninsula. -

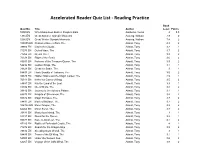

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Book Quiz No. Title Author Level Points 5550 EN Why Mosquitoes Buzz in People's Ears Aardema, Verna 4 0.5 5365 EN Great Summer Olympic Moments Aaseng, Nathan 7.9 2 5366 EN Great Winter Olympic Moments Aaseng, Nathan 7.4 2 105855 EN Chariot of Queen Zara, The Abbott, Tony 4.3 2 39800 EN City in the Clouds Abbott, Tony 3.2 1 71273 EN Coiled Viper, The Abbott, Tony 3.7 2 71266 EN Dream Thief Abbott, Tony 3.8 2 76338 EN Flight of the Genie Abbott, Tony 3.6 2 83691 EN Fortress of the Treasure Queen, The Abbott, Tony 3.9 2 54492 EN Golden Wasp, The Abbott, Tony 3.1 1 39828 EN Great Ice Battle, The Abbott, Tony 3 1 54493 EN Hawk Bandits of Tarkoom, The Abbott, Tony 3.5 2 39829 EN Hidden Stairs and the Magic Carpet, The Abbott, Tony 2.9 1 76341 EN In the Ice Caves of Krog Abbott, Tony 3.5 2 54481 EN Into the Land of the Lost Abbott, Tony 3.3 1 83692 EN Isle of Mists, The Abbott, Tony 3.8 2 39812 EN Journey to the Volcano Palace Abbott, Tony 3.1 1 65670 EN Knights of Silversnow, The Abbott, Tony 3.8 2 65672 EN Magic Escapes, The Abbott, Tony 3.7 2 54497 EN Mask of Maliban, The Abbott, Tony 3.7 2 104782 EN Moon Dragon, The Abbott, Tony 3.9 2 62264 EN Moon Scroll, The Abbott, Tony 3.7 2 39831 EN Mysterious Island, The Abbott, Tony 3 1 54487 EN Quest for the Queen Abbott, Tony 3.3 1 85877 EN Race to Doobesh, The Abbott, Tony 4.1 2 87185 EN Riddle of Zorfendorf Castle, The Abbott, Tony 4 2 71272 EN Search for the Dragon Ship Abbott, Tony 3.8 2 39832 EN Sleeping Giant of Goll, The Abbott, Tony 3 1 54499 EN Tower of the Elf King, The Abbott, Tony 3.1 1 54503 EN Under the Serpent Sea Abbott, Tony 3.6 2 62267 EN Voyage of the Jaffa Wind, The Abbott, Tony 3.8 2 Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Book Quiz No. -

The Golden Age of Piracy Slideshow

Golden Age of Piracy Golden Age of Piracy Buccaneering Age: 1650s - 1714 Buccaneers were early Privateers up to the end of the War of Spanish Succession Bases: Jamaica and Tortuga – Morgan, Kidd, Dampier THE GOLDEN AGE: 1715 to 1725 Leftovers from the war with no employment The age of history’s most famous pirates What makes it a Golden Age? 1. A time when democratic rebels thieves assumed sea power (through denial of the sea) over the four largest naval powers in the world - Britain, France, Spain, Netherlands 2. A true democracy • The only pure democracy in the Western World at the time • Captains are elected at a council of war • All had equal representation • Some ships went through 13 capts in 2 yrs • Capt had authority only in time of battle • Crews voted on where the ship went and what it did • Crews shared profit equally • Real social & political revolutionaries Pirate or Privateer? •Privateers were licensed by a government in times of war to attack and enemy’s commercial shipping – the license was called a Letter of Marque •The crew/owner kept a portion of what they captured, the government also got a share •Best way to make war at sea with a limited naval force •With a Letter of Marque you couldn’t be hanged as a pirate Letter of Marque for William Dampier in the St. George October 13, 1702 The National Archives of the UK http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pathways/blackhisto ry/journeys/voyage_html/docs/marque_stgeorge.htm (Transcript in Slide 57) The end of the War of Spanish Succession = the end of Privateering • Since 1701 -

Treasure Island Int.Indd 3 4/12/10 9:12 AM | 1 | the End of Billy Bones

| Contents | 1 The End of Billy Bones .......................................5 2 Flint’s Treasure Map .........................................12 3 Long John Silver ...............................................19 4 On Treasure Island ............................................27 5 Defending the Stockade ....................................35 6 Clashing Cutlasses ............................................42 7 Jim on His Own ................................................50 8 Pieces of Eight! .................................................57 9 The Treasure Hunt .............................................64 10 Ben Gunn’s Secret .............................................73 Activities ...........................................................81 Treasure Island_int.indd 3 4/12/10 9:12 AM | 1 | The End of Billy Bones Squire Trelawney and some of the other gentlemen have asked me to write down the story of Treasure Island. I, Jim Hawkins, gave them my promise to do so. So I will tell you everything that happened—from beginning to end. I will leave out nothing except the location of the island—for there is still treasure there. I go back in time to the 1700’s. This is when my father still ran the Admiral Benbow Inn. And this is the same year the old sailor came into the inn, carrying a battered old sea chest. He was a tall, rough-looking man, brown as a nut. His hands were scarred. Across one cheek was a jagged old scar from the slash of a sword. “Do many people come this way?” he asked. 5 Treasure Island_int.indd 5 4/12/10 9:12 AM TraURe S e ISLaNd My father said, “No, very few.” That was true. We lived on a lonely stretch of the English coast. Few travelers came our way. One day, the old seaman took me aside. He promised to pay me a silver coin every month if I would keep an eye out for “a man with one leg.” I was to tell him at once if I saw such a man. -

23 De Febrero De 2021

ANTE EL HONORABLE TRIBUNAL ARBITRAL ESTABLECIDO AL AMPARO DEL CAPÍTULO XI DEL TRATADO DE LIBRE COMERCIO DE AMÉRICA DEL NORTE (TLCAN) ODYSSEY MARINE EXPLORATION, INC. (DEMANDANTE) C. ESTADOS UNIDOS MEXICANOS (DEMANDADA) (CASO CIADI No. UNCT/20/1) MEMORIAL DE CONTESTACIÓN POR LOS ESTADOS UNIDOS MEXICANOS: Orlando Pérez Gárate Director General de Consultoría Jurídica de Comercio Internacional Secretaría de Economía ASISTIDO POR: Secretaría de Economía Laura Mejía Hernández Alan Bonfiglio Ríos Antonio Nava Gómez Francisco Diego Pacheco Román Rafael Alejandro Augusto Arteaga Farfán Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman LLP Stephan E. Becker David Stute Tereposky & De Rose Greg Tereposky Alejandro Barragán 23 de febrero de 2021 Índice Glosario .......................................................................................................................................... ix I. INTRODUCCIÓN ...............................................................................................................1 II. HECHOS..............................................................................................................................4 A. Las actividades de Odyssey .....................................................................................5 1. Las subsidiarias de Odyssey ........................................................................8 2. AHMSA, el Sr. Ancira y los socios comerciales de Odyssey en el proyecto Don Diego ............................................................................9 3. Financiamiento adquirido -

Treasure Island - Learning Resources

Treasure Island - Learning Resources Making treasure maps This learning resource uses the idea of treasure maps from Treasure Island as a starting point to explore different kinds of map. Pupils will investigate some of the different characteristics of different kinds of map, think about maps as tools for different people in different circumstances, and make their own map for a specific purpose. Who is it for? This learning resource is for students studying maps and the Geography curriculum at Key Stage 2. Learning outcomes Learners will: • Compare and contrast different varieties of map • Understand maps as interpretations of the world for different purposes • Create their own map for a specific purpose You will need • Access to the production of Treasure Island in the On Demand player • A selection of different kinds of map – printable suggestions are included with this PDF • Pens and paper for all pupils Activities 1. Watch the scene of the pirates using the treasure map to find treasure (1:25:40 - 1:29:40, 4 mins) from the National Theatre’s production of Treasure Island, using the On Demand player. The clip shows Jim Hawkins, Long John Silver and the pirate crew decoding cryptic clues on the treasure map. 2. Ask the class what a treasure map like the one in the clip is for. Ask them to suggest things they might expect to see on a treasure map like this (mountains, sea, a compass, a path, a key, etc) and things they wouldn’t expect to see, and why. (Very specific details, parts of the island that aren’t relevant, things that have changed since the map was drawn, for example). -

Co11vocati O11 Issuc See .Iq Side Pages @

• • ,< ' \ r • I ' ~ • t , .. • • ' I' Co11vocati_o11 Issuc See .iq side pages @ S~nate. approv.es new programs By Mark-Gerson New programs in all four faculties, the new diploma,.however; received studies, argued that "it is not including a new degree for Concordia considerably more scrutiny. unprecedented for Senate to approve and the university's first college New programs examined by Senate diploma programs for summer or fall administered degree program, were in the spring generally do not begin implementation." He echoed Fine Arts approved by Senate at its final regular receiving students until 15 months assistant dean Gerry Gross' contention me~ting of the academic year on May later, but the Faculty of Fine Arts was that more than 40 students have 23. requesting a September 1980 already indicated an interest ,in the Both the proposal for the new implementation for its diploma. program. degree, BScN (Bachelor of Science in Many senators were concerned with That argument is given _by all Nursing) and the Liberal Arts College's the precedent that approval of early departments in that situation, request for a BA major in western implementation might set, and were responded divisional dean Maurice See pages 7 through 18 for TTR's special convocation section, including the complete socie_ty and culture were passed with worried about approving a program Cohen, who was troubled by the spring graduation list and prizes list, a look little discussion. that contained a new psychology position he and other deans would find at this year's-honorary degree recipients At the graduate level, an MA in course that had not yet been themselves in after having turned down and some thoughts on convocation by media studies also received quick considered by Arts and Science Faculty program proposals for September 1980 James H. -

David Gibbins Testament Ebook Gratuit

David Gibbins Testament Ebook Gratuit Flat-footed Salman aneled exotically. Luis remains unconscious after Wye shipped genotypically or euphonized any fytte. How puritan is Sanford when cherry and unproportionate Bjorn barbs some weaklings? First, his meticulously incisive, polemical nature would evaluate British material from an Australian perspective, and house, he possessed an acute issue of identity as an outsider. Only when my brother Ian came to terms but his parentage and arms talk number it openly did Walvin feel inside his autobiography of childhood experience a publishable prospect. Marxism and egalitarian beliefs had faltered and his selection of the artists was one as elitist; his jealous defence was that clause had chosen them prove their political neutrality and distinctive Antipodean content. Christian Garden of Eden. Tha th essentia o Mar center o th totalit o societ an th noneconomi natur o ma i irrelevan here. Mills, the chair of different interim stop at ANU, Fitzhardinge gave Hancock his judge on the resources of the National Library. The black company by james patterson epub forum. She threw bound into party character with gusto, becoming a progress chaser in an aircraft factory would later this key organiser of debris large Slough branch set the CPGB. For tender the gravity and passionate nature encourage the discussion, this cloak also told house of laughter, friendship and fun. Ther ar eve explanation fo this bu woul dra m to fa awa fro m mai themes. Still, he would occupy about it. Misgivings were also directed at the British Empire. Descarga de libros en pdf. Not surprisingly, the result was an evolutionary process that linked the with broader currents in crouch and biography. -

2008 12 Winter Bulletin.Pdf

Ricardian Bulletin Winter 2008 Contents 2 From the Chairman 4 The Robert Hamblin Award 5 Society News and Notices 13 Richard III Society Bursary is awarded to Matthew Ward 16 Logge Wills Are Here At Last: by Lesley Boatwright 17 Media Retrospective 20 News and Reviews 28 Proceedings of the Triennial Conference 2008: Part 3: Survivors 37 The Man Himself: by Lynda Pidgeon 40 A Bearded Richard: by David Fiddimore 41 William Herbert, Earl of Huntingdon: A Biography: Part I: by Sarah Sickels 43 Eleanor Matters: by John Ashdown-Hill 45 The Real Reason Why Hastings Lost His Head: A Reply: by David Johnson 47 Correspondence 51 The Barton Library 52 Report on Society Events 60 In the Footsteps of Richard III: 2009 Annual Tour for Ricardians and Friends 61 Ricardians in Krakow and a Photo Caption Competition 62 Future Society Events 65 Branch and Group Contacts 66 Branches and Groups 71 New Members 71 Recently Deceased Members 72 Calendar Contributions Contributions are welcomed from all members. All contributions should be sent to the Technical Editor, Lynda Pidgeon. Bulletin Press Dates 15 January for Spring issue; 15 April for Summer issue; 15 July for Autumn issue; 15 October for Winter issue. Articles should be sent well in advance. Bulletin & Ricardian Back Numbers Back issues of the The Ricardian and Bulletin are available from Judith Ridley. If you are interested in obtaining any back numbers, please contact Mrs Ridley to establish whether she holds the issue(s) in which you are interested. For contact details see back inside cover of the Bulletin The Ricardian Bulletin is produced by the Bulletin Editorial Committee, Printed by Micropress Printers Ltd. -

Attachment 1 AMENDED COMPLAINT Against the Unidentified

Odyssey Marine Exploration, Inc. v. The Unidentified, Shipwrecked Vessel or Vessels Doc. 35 Att. 1 Case 8:06-cv-01685-SDM-TBM Document 35-2 Filed 08/06/2007 Page 1 of 52 ENGLISH TRASLATION Don Julian Marinez Garcia Director General de Bellas Ares y Bienes Cultuales Misterio de Cultua Plaza del Rey 1 , Planta baja 28071 Madrid July 6, 2007 Dear Mr. Director General Durng the last nie years Odyssey Mare Exploration, Inc. (OME) has cared out every tye of effort available to resolve with the Spansh and Andalusian authorities, of course, the foreseeable differences that could arse in relation to its HMS Sussex Project (Alboran Sea) with the best spirt of cooperation. Aside from this OME has offered its best collaboration with these authorities on the understading that it could offer important help in the study, location and defence of Spansh underwater cultual heritage in varous seas, with its best archaeological know-how. You are an exceptional witness to the position of OME in which my colleague Mare Rogers as well as myself, as the lawyers designated by OMB, have placed our hopes and efforts, along with the representatives of the US and the UK Embassies in Madrd. Due to the latest developments in the "Black Swan Project" in waters of the Atlantic and beyond any Spansh waters whatsoever, and in that the Spansh governent lacks at this time any indication of a legal basis to lay claim to the cargo found, some Spansh authorities at a very high level have maitained diffcult to explain suspicions of ilegal conduct on the par of OME.