Sterrett-Krause Current Curriculum Vitae CV

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reflecting Antiquity Explores the Rediscovery of Roman Glass and Its Influence on Modern Glass Production

Reflecting Antiquity explores the rediscovery of Roman glass and its influence on modern glass production. It brings together 112 objects from more than 24 lenders, featuring ancient Roman originals as well as the modern replicas they inspired. Following are some of the highlights on view in the exhibition. Portland Vase Base Disk The Portland Vase is the most important and famous work of cameo glass to have survived from ancient Rome. Modern analysis of the vase, with special attention to the elongation of the bubbles preserved in the lower body, suggest that it was originally shaped as an amphora (storage vessel) with a pointed base. At some point in antiquity, the vessel suffered some damage and acquired this replacement disk. The male figure and the foliage on the disk were not carved by the same Unknown artist that created the mythological frieze on the vase. Wearing a Phrygian cap Portland Vase Base Disk Roman, 25 B.C.–A.D. 25 and pointing to his mouth in a gesture of uncertainty, the young man is Paris, a Glass Object: Diam.: 12.2 cm (4 13/16 in.) prince of Troy who chose Aphrodite over Hera and Athena as the most beautiful British Museum. London, England GR1945.9-27.2 goddess on Mount Olympus. It is clear from the way the image is truncated that VEX.2007.3.1 it was cut from a larger composition, presumably depicting the Judgment of Paris. The Great Tazza A masterpiece of cameo-glass carving, this footed bowl (tazza) consists of five layers of glass: semiopaque green encased in opaque white, green, a second white, and pink. -

Eclectic Antiquity Catalog

Eclectic Antiquity the Classical Collection of the Snite Museum of Art Compiled and edited by Robin F. Rhodes Eclectic Antiquity the Classical Collection of the Snite Museum of Art Compiled and edited by Robin F. Rhodes © University of Notre Dame, 2010. All Rights Reserved ISBN 978-0-9753984-2-5 Table of Contents Introduction..................................................................................................................................... 1 Geometric Horse Figurine ............................................................................................................. 5 Horse Bit with Sphinx Cheek Plates.............................................................................................. 11 Cup-skyphos with Women Harvesting Fruit.................................................................................. 17 Terracotta Lekythos....................................................................................................................... 23 Marble Lekythos Gravemarker Depicting “Leave Taking” ......................................................... 29 South Daunian Funnel Krater....................................................................................................... 35 Female Figurines.......................................................................................................................... 41 Hooded Male Portrait................................................................................................................... 47 Small Female Head...................................................................................................................... -

History of Horticulture: Lecture 18 1

History of Horticulture: Lecture 18 Lecture 18 Roman Agricultural History Pompeii and Mount Vesuvius View from the Tower of Mercury on the Pompeii city wall looking down the Via di Mercurio toward the forum 1 History of Horticulture: Lecture 18 Rome 406–88 BCE Source: Harper Atlas of World History, 1992. Rome 241–27 BCE Source: Harper Atlas of World History, 1992. Rome 193–211 Source: Harper Atlas of World History, 1992. 2 History of Horticulture: Lecture 18 Carthage Founded 814 BCE in North Africa Result of Phoenician expansion North African city-state opposite Sicily Mago, 350 BCE, Father of Agriculture Agricultural author wrote a 28 volume work in Punic, A language close to Hebrew. Roman Senate ordered the translation of Mago upon the fall of Carthage despite violent enmity between states. One who has bought land should sell his town house so that he will have no desire to worship the households of the city rather than those of the country; the man who takes great delight in his city residence will have no need of a country estate. Quotation from Columella after Mago Hannibal Capitoline Museums Hall of Hannibal Jacopo Ripanda (attr.) Hannibal in Italy Fresco Beginning of 16th century Roman History 700 BCE Origin from Greek Expansion 640–520 Etruscan civilization 509 Roman Republic 264–261 Punic wars between Carthage and Rome 3 History of Horticulture: Lecture 18 Roman Culture Debt to Greek, Egyptian, and Babylonian Science and Esthetics Roman expansion due to technology and organization Agricultural Technology Irrigation Grafting Viticulture and Enology Wide knowledge of fruit culture, pulses, wheat Legume rotation Fertility appraisals Cold storage of fruit Specularia—prototype greenhouse using mica Olive oil for cooking and light Ornamental Horticulture Hortus (gardens) Villa urbana Villa rustica, little place in the country Formal gardens of wealthy Garden elements Frescoed walls, statuary, fountains trellises, pergolas, flower boxes, shaded walks, terraces, topiary Getty Museum reconstruction of the Villa of the Papyri. -

Romans Had So Many Gods

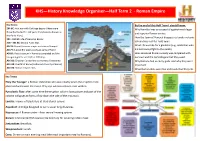

KHS—History Knowledge Organiser—Half Term 2 - Roman Empire Key Dates: By the end of this Half Term I should know: 264 BC: First war with Carthage begins (There were Why Hannibal was so successful against much lager three that lasted for 118 years; they become known as and superior Roman armies. the Punic Wars). How the town of Pompeii disappeared under volcanic 254 - 191 BC: Life of Hannibal Barker. ash and was lost for 1500 years. 218—201 BC: Second Punic War. AD 79: Mount Vesuvius erupts and covers Pompeii. What life was like for a gladiator (e.g. celebrities who AD 79: A great fire wipes out huge parts of Rome. did not always fight to the death). AD 80: The colosseum in Rome is completed and the How advanced Roman society was compared with inaugural games are held for 100 days. our own and the technologies that they used. AD 312: Emperor Constantine converts to Christianity. Why Romans had so many gods. And why they were AD 410: The fall of Rome (Goths sack the city of Rome). important. AD 476: Roman empire ends. What Roman diets were like and foods that they ate. Key Terms Pliny the Younger: a Roman statesman who was nearby when the eruption took place and witnessed the event. Only eye witness account ever written. Pyroclastic flow: after some time the eruption column loses power and part of the column collapses to form a flow down the side of the mountain. Lanista: Trainer of Gladiators at Gladiatorial school. Aqueduct: A bridge designed to carry water long distances. -

Archaeometric Studies on a Pompeian Blue Glass Fragment from Regio I, Insula 14 for the Characterization of Glassmaking Technology

Archaeometric studies on a Pompeian blue glass fragment from Regio I, Insula 14 for the characterization of glassmaking technology Monica Gelzo University of Naples Federico II: Universita degli Studi di Napoli Federico II Gaetano Corso Università di Foggia: Universita degli Studi di Foggia Alessandro Vergara Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II: Universita degli Studi di Napoli Federico II Manuela Rossi Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II: Universita degli Studi di Napoli Federico II Oto Miedico Istituto Zooprolattico Sperimentale della Puglia e della Basilicata Ottavia Arcari Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II: Universita degli Studi di Napoli Federico II Antonio Eugenio Chiaravalle Istituto Zooprolattico Sperimentale della Puglia e della Basilicata Ciro Piccioli AISES Paolo Arcari ( [email protected] ) University of Naples Federico II https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9582-0850 Research Article Keywords: Pompeii, Primary production, Raw materials, Natron-lime glass, Sand, Western Mediterranean, glass compositions Posted Date: August 3rd, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-754282/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/19 Abstract A Pompeian glass sample found in Reg. I, Insula 14, during the 1950’s Pompeii excavation was examined by Raman and Fourier transformed infrared spectroscopy, scanning electron microscopy, and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. The analyzed specimen was selected based on its intense blue color and its well- preserved aspect. The purpose of the work was the chemical characterization of Pompeii’s glass in correlation to the actual knowledge of Roman glassmaking technology from the Mediterranean area. -

Women in Pompeii Author(S): Elizabeth Lyding Will Source: Archaeology, Vol

Women in Pompeii Author(s): Elizabeth Lyding Will Source: Archaeology, Vol. 32, No. 5 (September/October 1979), pp. 34-43 Published by: Archaeological Institute of America Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41726375 . Accessed: 19/03/2014 08:08 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Archaeological Institute of America is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Archaeology. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 170.24.130.117 on Wed, 19 Mar 2014 08:08:22 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Wfomen in Pompeii by Elizabeth Lyding Will year 1979 marks the 1900th anniversary of the fatefulburial of Pompeii, Her- The culaneum and the other sitesengulfed by the explosion of Mount Vesuvius in a.d. 79. It was the most devastatingdisaster in the Mediterranean area since the volcano on Thera erupted one and a half millenniaearlier. The suddenness of the A well-bornPompeian woman drawn from the original wall in theHouse Ariadne PierreGusman volcanic almost froze the bus- painting of by onslaught instantly ( 1862-1941), a Frenchartist and arthistorian. Many tling Roman cityof Pompeii, creating a veritable Pompeianwomen were successful in business, including time capsule. -

Rome Conquers the Western Mediterranean (264-146 B.C.) the Punic Wars

Rome Conquers the Western Mediterranean (264-146 B.C.) The Punic Wars After subjugating the Greek colonies in southern Italy, Rome sought to control western Mediterranean trade. Its chief rival, located across the Mediterranean in northern Africa, was the city-state of Carthage. Originally a Phoenician colony, Carthage had become a powerful commercial empire. Rome defeated Carthage in three Punic (Phoenician) Wars and gained mastery of the western Mediterranean. The First Punic War (264-241 B.C.) Fighting chiefly on the island of Sicily and in the Mediterranean Sea, Rome’s citizen-soldiers eventually defeated Carthage’s mercenaries(hired foreign soldiers). Rome annexed Sicily and then Sardinia and Corsica. Both sides prepared to renew the struggle. Carthage acquired a part of Spain and recruited Spanish troops. Rome consolidated its position in Italy by conquering the Gauls, thereby extending its rule northward from the Po River to the Alps. The Second Punic War (218-201 B.C.) Hannibal, Carthage’s great general, led an army from Spain across the Alps and into Italy. At first he won numerous victories, climaxed by the battle of Cannae. However, he was unable to seize the city of Rome. Gradually the tide of battle turned in favor of Rome. The Romans destroyed a Carthaginian army sent to reinforce Hannibal, then conquered Spain, and finally invaded North Africa. Hannibal withdrew his army from Italy to defend Carthage but, in the Battle of Zama, was at last defeated. Rome annexed Carthage’s Spanish provinces and reduced Carthage to a second-rate power. Hannibal of Carthage Reasons for Rome’s Victory • superior wealth and military power, • the loyalty of most of its allies, and • the rise of capable generals, notably Fabius and Scipio. -

Contextualizing the Archaeometric Analysis of Roman Glass

Contextualizing the Archaeometric Analysis of Roman Glass A thesis submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati Department of Classics McMicken College of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts August 2015 by Christopher J. Hayward BA, BSc University of Auckland 2012 Committee: Dr. Barbara Burrell (Chair) Dr. Kathleen Lynch 1 Abstract This thesis is a review of recent archaeometric studies on glass of the Roman Empire, intended for an audience of classical archaeologists. It discusses the physical and chemical properties of glass, and the way these define both its use in ancient times and the analytical options available to us today. It also discusses Roman glass as a class of artifacts, the product of technological developments in glassmaking with their ultimate roots in the Bronze Age, and of the particular socioeconomic conditions created by Roman political dominance in the classical Mediterranean. The principal aim of this thesis is to contextualize archaeometric analyses of Roman glass in a way that will make plain, to an archaeologically trained audience that does not necessarily have a history of close involvement with archaeometric work, the importance of recent results for our understanding of the Roman world, and the potential of future studies to add to this. 2 3 Acknowledgements This thesis, like any, has been something of an ordeal. For my continued life and sanity throughout the writing process, I am eternally grateful to my family, and to friends both near and far. Particular thanks are owed to my supervisors, Barbara Burrell and Kathleen Lynch, for their unending patience, insightful comments, and keen-eyed proofreading; to my parents, Julie and Greg Hayward, for their absolute faith in my abilities; to my colleagues, Kyle Helms and Carol Hershenson, for their constant support and encouragement; and to my best friend, James Crooks, for his willingness to endure the brunt of my every breakdown, great or small. -

The Road to Nicea a Survey of the Regional Differences Influencing the Development of the Doctrine of the Trinity

JBTM The Bible and Theology 120 THE ROAD TO NICEA A SURVEY OF THE REGIONAL DIFFERENCES INFLUENCING THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE DOCTRINE OF THE TRINITY Christopher J. Black, Ph.D. Dr. Black is Assistant Researcher to the Provost and Adjunct Instructor in Theology at New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary New Orleans, Louisiana Introduction uring the opening centuries of Christianity, the early church quickly came to realize that Dcertain ideas had to be settled if it was going to survive. The first of these foundational doctrines addressed how Christ related to the Father, and the Holy Spirit. Early Christian theologians understood that the development of a deeper concept of God was required. The establishment of Christianity as monotheistic, while maintaining the divinity of the Father, Son, and Spirit, was at issue. But how could God be one and three? The answer found a voice in the doctrine of the Trinity. In AD 325 bishops gathered to draft a document intended to explain definitively Christ’s role in the Godhead. The doctrine of the Trinity, however, did not begin in Nicea. The issue had been burning for centuries. The question before the church essentially was a Christological one: Who is Jesus in relationship to God? This question leads to the obvious dilemma. If Jesus is God, how can Christianity claim to be monotheistic? And if Jesus is not God, how can Christianity claim to be theistic?1 Furthermore, while the Nicene Creed emphasized the Christological question, and included the Spirit—thus maintaining a trinitarian over a binitarian doctrine—most debate centered on the relationship between the Father and the Son. -

Carthage Was Indeed Destroyed

1 Carthage was indeed destroyed Introduction to Carthage According to classical texts (Polybe 27) Carthage’s history started with the Phoenician queen Elissa who was ousted from power in Tyre and in 814 BC settled with her supporters in what is now known as Carthage. There might have been conflicts with the local population and the local Berber kings, but the power of the Phoenician settlement Carthage kept growing. The Phoenicians based in the coastal cities of Lebanon constituted in the Mediterranean Sea a large maritime trade power but Carthage gradually became the hub for all East Mediterranean trade by the end of the 6th century BC. Thus Carthage evolved from being a Phoenician settlement to becoming the capital of an empire (Fantar, M.H., 1998, chapter 3). The local and the Phoenician religions mixed (e.g. Tanit and Baal) and in brief Carthage developed from its establishment in roughly 800 BC and already from 6th century BC had become the centre for a large empire of colonies across Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Spain, and the islands of Mallorca, Sardinia, and Sicily (Heimburger, 2008 p.36). Illustration: The empire of Carthage prior to the 1st Punic war in 264 BC, encyclo.voila.fr/wiki/Ports_puniques_de_Carthage 2010 Following two lost wars with the rising Rome (264-241 BC and 218-201 BC) Carthage was deprived of its right to engage in wars but experienced a very prosperous period as a commercial power until Rome besieged the city in 149 BC and in 146 BC destroyed it completely 25 years later Rome decided to rebuild the city but not until 43 BC was Carthage reconstructed as the centre for Rome’s African Province. -

Early History of Stained Glass

chapter 2 Early History of Stained Glass Francesca Dell’Acqua The destruction of a large number of medieval glazed light, and the interaction between natural and artificial windows in the 18th century can be attributed both to light. An emphasis on materiality, combined with the the desire for more light in buildings, reflecting the in- study of past building practices, as well as specific aesthet- tellectual and political desire to overcome the obscu- ic and cultural ambitions, currently informs the research rantism of past ages, and to the turmoil of the French on the origins and later developments of stained glass.4 Revolution. This destruction generated reflections, mu- seum displays, and scholarship on the history of stained glass. According to the early histories of western stained 1 Roman Glass glass, written between the late 18th and 19th centuries, the origins of the technique remained unknown, thus it In his famous treatise written between 30– 15 b.c. under was hard to explain how the medium developed before the first Roman emperor Augustus, Vitruvius suggests culminating in the masterpieces of the Gothic period.1 methods to increase the quantity and quality of natural French, English, and German scholars collected written light when planning a room, especially in densely pop- and material evidence to demonstrate that medieval ulated cities.5 Windows had the combined functions stained glass had been invented in their own countries. of letting in natural light (lumen), allowing ventilation Despite having divergent opinions, they actually provid- (aer), and possibly opening up to a view (prospectus), ed converging evidence, which demonstrated that the especially in the triclinia, i.e. -

Economic Role of the Roman Army in the Province of Lower Moesia (Moesia Inferior) INSTITUTE of EUROPEAN CULTURE ADAM MICKIEWICZ UNIVERSITY in POZNAŃ

Economic role of the Roman army in the province of Lower Moesia (Moesia Inferior) INSTITUTE OF EUROPEAN CULTURE ADAM MICKIEWICZ UNIVERSITY IN POZNAŃ ACTA HUMANISTICA GNESNENSIA VOL. XVI ECONOMIC ROLE OF THE ROMAN ARMY IN THE PROVINCE OF LOWER MOESIA (MOESIA INFERIOR) Michał Duch This books takes a comprehensive look at the Roman army as a factor which prompted substantial changes and economic transformations in the province of Lower Moesia, discussing its impact on the development of particular branches of the economy. The volume comprises five chapters. Chapter One, entitled “Before Lower Moesia: A Political and Economic Outline” consti- tutes an introduction which presents the economic circumstances in the region prior to Roman conquest. In Chapter Two, entitled “Garrison of the Lower Moesia and the Scale of Militarization”, the author estimates the size of the garrison in the province and analyzes the influence that the military presence had on the demography of Lower Moesia. The following chapter – “Monetization” – is concerned with the financial standing of the Roman soldiery and their contri- bution to the monetization of the province. Chapter Four, “Construction”, addresses construction undertakings on which the army embarked and the outcomes it produced, such as urbanization of the province, sustained security and order (as envisaged by the Romans), expansion of the economic market and exploitation of the province’s natural resources. In the final chapter, entitled “Military Logistics and the Local Market”, the narrative focuses on selected aspects of agriculture, crafts and, to a slightly lesser extent, on trade and services. The book demonstrates how the Roman army, seeking to meet its provisioning needs, participated in and contributed to the functioning of these industries.