Whisker Touch Guides Canopy Exploration in a Nocturnal, Arboreal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MC1911 Dormousetranslocation-1

MAMMAL COMMUNICATIONS Volume 6 ISSN 2056-872X (online) Patrick James © Nick C. Downs, Mike Dean, David Wells, and Alisha Wouters Displacing and translocating hazel dormice Mammal Communications Displacing and translocating hazel dormice (Muscardinus avellanarius) as road development mitigation measures. Nick C. Downs1,2*, Mike Dean3, David Wells4, and Alisha Wouters5 ABSTRACT Road development can remove valuable wildlife habitat and reduce habitat connectivity. Where such works impact on European Protected Species in the UK, such as hazel dormice (Muscardinus avellanarius), mitigation is required to satisfy the relevant Statutory Nature Conservation Organisation licensing process. The study described here concerns the removal of dense road verge landscape planting occupied by hazel dormice prior to the construction of a new road junction and slip roads on a dual carriageway in Wales. Pre-construction monitoring started in May 2007, followed by vegetation clearance between August and September. Dormice were displaced into retained habitat through maximum daily vegetation clearance of 30 m lengths (varying widths), in parallel with translocation. This process resulted in the discovery of 48 natural (i.e. not within a nest box) dormouse nests, and the capture of 29 dormice for translocation; 90% were successfully released. Whilst within soft-release cages prior to release, dormice preferred a diet of blackberries (Rubus fruticosus agg.) and freshly picked hazel (Corylus avellana) nuts, prompting a recommendation for early Autumn (mid-August -

Decayed Trees As Resting Places for Japanese Dormouse, Glirulus Japanicus During the Active Period

Decayed trees as resting places for Japanese dormouse, Glirulus japanicus during the active period HARUKA AIBA, MANAMI IWABUCHI, CHISE MINATO, ATUSHI KASHIMURA, TETSUO MORITA AND SHUSAKU MINATO Keep Dormouse Museum, 3545 Kiyosato, Takane-cho, Hokuto-city, Yamanashi, 407-0301, Japan Decayed trees were surveyed for their role as a resting place for non-hibernating dormice at two sites, at southwest of Mt. Akadake in Yamanashi Prefecture (35°56’N, 138°25’E). A telemeter located three dormice, which frequently used decayed trees in the daytime, with two at more than 50% of the times. The survey also showed decayed trees made up only about one fourth of all trees present in various conditions in habitat forests. These two data indicated that decayed trees are an important resting place for non-hibernating dormice in the daytime and provide favorable environmental conditions for inhabitation. Using national nut hunt surveys to find protect and raise the profile of hazel dormice throughout their historic range NIDA AL FULAIJ People’s Trust for Endangered Species (list of authors to come) The first Great Nut Hunt (GNH), launched in 1993 had 6500 participants, identifying 334 new sites and thus confirming the presence of dormice in 29 counties in England and Wales. In 2001, 1200 people found 136 sites with positive signs of hazel dormice. The third GNH started in 2009. Over 4000 people registered and to date almost 460 woodland or hedgerow surveys have been carried out, in conjunction with a systematic survey of 286 woodlands on the Isle of Wight. Of the 460 surveys carried out by the general public, 74 found evidence of dormice. -

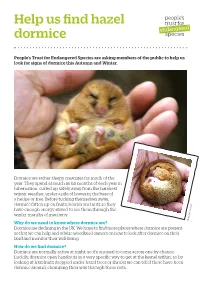

Help Us Find Hazel Dormice

Help us find hazel dormice People’s Trust for Endangered Species are asking members of the public to help us look for signs of dormice this Autumn and Winter. Dormice are rather sleepy creatures for much of the year. They spend as much as six months of each year in hibernation, curled up safely away from the harshest winter weather, under a pile of leaves in the base of a hedge or tree. Before tucking themselves away, dormice fatten up on fruits, berries and nuts so they have enough energy stored to see them through the winter months of inactivity. Why do we need to know where dormice are? Rhys Owen-Roberts Dormice are declining in the UK. We hope to find more places where dormice are present so that we can help and advise woodland owners on how to look after dormice on their land and monitor their well-being. How do we find dormice? Dormice are normally active at night, so it’s unusual to come across one by chance. Luckily, dormice open hazelnuts in a very specific way to get at the kernel within; so by looking at hazelnuts dropped under hazel trees or shrubs we can tell if there have been dormice around, chomping their way through these nuts. How to get involved We need people to look for dormouse-nibbled hazel nuts and let us know what they find. A nut hunt is very simple and a great way to spend some time outside on an autumnal or wintery day. It can be a fun family activity too. -

Forest Ecology and Management

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE Habitat preferences of hazel dormice Muscardinus avellanarius and the effects of tree-felling on their movement AUTHORS Goodwin, CED; Hodgson, DJ; Bailey, S; et al. JOURNAL Forest Ecology and Management DEPOSITED IN ORE 09 July 2018 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10871/33405 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication Forest Ecology and Management 427 (2018) 190–199 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Forest Ecology and Management journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/foreco Habitat preferences of hazel dormice Muscardinus avellanarius and the effects T of tree-felling on their movement Cecily E.D. Goodwina, David J. Hodgsonb, Sallie Baileyc, Jonathan Benniea,d, ⁎ Robbie A. McDonalda, a Environment and Sustainability Institute, University of Exeter, Penryn Campus, Penryn TR10 9FE, United Kingdom b Centre for Ecology and Conservation, University of Exeter, Penryn Campus, Penryn TR10 9FE, United Kingdom c Forest Enterprise Scotland, Dumfries and Borders Forest District, Ae Village, Parkgate, Dumfries DG1 1QB, United Kingdom d Department of Geography, University of Exeter, Penryn TR10 9FE, United Kingdom ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Modern management of multifunctional woodlands must address many and various demands, including for BACI design recreation, timber production and the conservation of biodiversity. The responses of individuals and populations Habitat preference of protected species to woodland management and habitat change are often not well understood. -

Somerset's Ecological Network

Somerset’s Ecological Network Mapping the components of the ecological network in Somerset 2015 Report This report was produced by Michele Bowe, Eleanor Higginson, Jake Chant and Michelle Osbourn of Somerset Wildlife Trust, and Larry Burrows of Somerset County Council, with the support of Dr Kevin Watts of Forest Research. The BEETLE least-cost network model used to produce Somerset’s Ecological Network was developed by Forest Research (Watts et al, 2010). GIS data and mapping was produced with the support of Somerset Environmental Records Centre and First Ecology Somerset Wildlife Trust 34 Wellington Road Taunton TA1 5AW 01823 652 400 Email: [email protected] somersetwildlife.org Front Cover: Broadleaved woodland ecological network in East Mendip Contents 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................... 1 2. Policy and Legislative Background to Ecological Networks ............................................ 3 Introduction ............................................................................................................... 3 Government White Paper on the Natural Environment .............................................. 3 National Planning Policy Framework ......................................................................... 3 The Habitats and Birds Directives ............................................................................. 4 The Conservation of Habitats and Species Regulations 2010 .................................. -

Hazel Dormouse Dormice Might Roll Outoftheirwinter Nestsand Woodsmen Cutcoppice Inautumn,Hibernating Hazel Coppice Inengland

fact FILE Extremely elusivehazel and increasingly rare, the hazeldormouse dormouse is unlike other rodents, being long-lived and highly specialised in its ability to hibernate. COMMON NAMES Common dormouse, hazel dormouse, French names muscardin, croquenoix and rat-d’or; sleep-meece (Suffolk). ScIENTIFIC NAME Muscardinus avellanarius DESCRIPTION Bright golden colour with thick furry tail and big black eyes. Head-body length: 6–9cm, tail length: 5.5–8cm. Weight: 15–30g, lifespan: Up to 5 years. Adults weigh about 20g in the summer, but can fatten up to 35g just before hibernation. HABITAT Deciduous woodland and thick, overgrown hedgerows. Thought to prefer mixed hazel coppice woodland which provides a varied diet throughout the year. However dormice are also found in other scrub and hedgerow habitats, and even conifer plantations. DIET Flowers, particularly the pollen, are important. Bramble provides both pollen in the spring and berries in the autumn. Fruits, hazelnuts, beechmast and sweet chestnuts, as well as aphids and other small insects. Hazel, honeysuckle, bramble and oak are probably the most important food sources. HABITS Dormice are nocturnal, alternating bursts of activity with periods of rest. Breeding males live alone, whilst females and non-breeding males are often found nesting together outside the breeding season. Sometimes the same male and female will live together in successive years. Dormice are mainly arboreal in the summer, rarely crossing open ground. BREEDING 3–7 blind and naked young are born usually in July or August. The babies remain with their mother in her nest for up to about 6 weeks, longer than most small rodents. -

Dormouse Wildlife Profile

Monitoring & Research Ecology Groups Wildlife Profiles: Hazel Dormouse By Henry Stanier What? Naturally rare, the Hazel or Common dormouse Photo by Henry Stanier (Muscardinus avellanarius), is unlike other rodents, being long-lived and highly specialised in its ability to hibernate. It has a variety of names; French names include muscardin, croquenoix and rat-d’or; sleep-meece in Suffolk but whatever it is called it is a popular species of small mammal with the public. Its bright golden colour, thick furry tail, big black eyes make it very attractive. The dormouse has a head-body of 6–9cm. It is the only small mammal in the UK with a furry tail, 5.5–8cm in length. It weighs between 15–30g and is unusually long-lived, with a lifespan of up to 5 years. The diet of dormice is an interesting one, with flowers, particularly the pollen, being important. Bramble is a significant species, or group of species in wildlife conservation, providing pollen in the spring and berries in the autumn, and dormice feed on both. Fruits, hazelnuts, beech mast and sweet chestnuts, as well as aphids and other small insects are also eaten. Hazel, honeysuckle, bramble and oak are probably the most important food sources. Their predators include cats, owls and weasels but food availability is one of the most important factors in their survival, especially when trying to survive the winter, a time when they can be easily disturbed as they hibernate on the woodland floor, at the surface. Where? The Hazel Dormouse is a species of scrub and woodland understorey (the lower growing trees and shrubs found in such places). -

Thedormouse Monitor

spring 2011 thedormouse monitor the newsletter of the national dormouse monitoring programme people’s trust for endangered species | INSIDE Releasing captive-bred dormice the fi rst ever reintroduction Underpasses for dormice? Edible dormice studies from the continent spring 2011 Welcome Contents Yorkshire dormouse release update 3 Tribute to Jonathan Woods 3 Edge Wood study of dormice 4 A long-term study of edible dormice, Bucks 5 Haslemere hedgerow project 6 Welcome to the spring edition of The Dormouse Warwickshire Dormouse Conservation Group 7 Monitor. We’ve lots of interesting articles for you First dormouse release Hailey Wood, Hertfordshire 1992 8 on recent and long-term research projects - both Shooters are leading on a new hazel dormouse project in Cheshire 10 here and on the continent. Karin Lebl has collected Underpasses for dormice? 12 data from fi ve long-term studies of edible dormice Dormouse activity on the A30 in Cornwall 13 in fi ve diff erent countries and looked at their diff erent Survival rates of hibernating Glis glis 14 rates of mortality and how that was aff ected by An easy way to reduce PIT-tag loss in rodents 15 whether they were breeding or not. We also have Alessio The eff ects of habitat loss and fragmentation on dormice in central Italy 16 Mortelliti’s report on his work assessing what impact The behaviour of dormice in hedgerows with gaps 18 hedgerow connectivity has on dormouse populations in Training courses and news 20 the Italian landscape. Encouragingly we also have news of several projects that are relying on the goodwill and eff orts of numerous People's Trust for Endangered Species 15 Cloisters House volunteers - all keen to help, 8 Battersea Park Road especially where dormice are London concerned. -

Planning with Dormice in Mind Taking a Closer Look at What Happens When Developers Build on Or Near to Dormouse Sites

people’s trust for endangered The Dormouse species Monitor WINTER 2014 Planning with dormice in mind Taking a closer look at what happens when developers build on or near to dormouse sites Dormice in tree crevices Dormice in literature Taking at look at genes Henry Andrews shares his Detlev Seibert began A few years ago a hazel photos and experiences of collecting books about dormouse turned up in finding dormice nesting in dormice before the internet Ireland. Where was it from? tree crevices during his bat made searching easier - now Debbie Glass investigates surveys in Somerset. he has a vast collection. and reports. 03 Ian White reports on the 2014 dormouse release James Chubb hosted a woodland 04 management training day at The Donkey Sanctuary in Devon Detlev Seibert, from Germany, has 05 spent years collecting books that feature tales of hazel dormice 07 19 06 Henry Andrews shares his experiences of finding dormice in tree crevices Feeding dormice in her garden is a 06 nightly occurance for Caroline Dilke Rachel Bates lends a hand, training In this issue 07 up new monitors on the PTES nature reserve 12 08 A review of the Danish dormouse 06 conference Debbie Glass takes a closer look at 10 the genetics of our hazel dormice Rimvydas Juškaitis and Laima 12 Baltrūnaitė look at what dormice in Lithuania eat Alice Mouton asks how many 14 species of hazel dormice there are? Li Li Williams explains how dormice 16 are taken into account during building developments in Devon Stephen Carroll looks at how 18 planning impacts on our dormice Spiders have been hitching a ride 20 with Alison Looser Where do dormice hibernate, asks 20 John Prince? Welcome This year has been an exciting one at PTES. -

Hazel Dormouse Ecology and Conservation in Woodlands

Hazel dormouse ecology and conservation in woodlands Submitted by Cecily E D Goodwin to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Biological Sciences, Jan 2018. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. (Signature)……………………………………………………………………………… 1 2 Abstract The extent and quality of forested habitats have changed across Europe and as a result many forest species have suffered declines and range contractions. European legislation has been introduced to conserve those species that have been negatively impacted by widespread land-use changes. In order to assess the needs of declining species and the efficacy of these protective measures, the effects of habitat type, configuration and management on individuals and populations needs to be understood. In this thesis, I have investigated patterns and drivers of variation in the status of populations of hazel dormouse Muscardinus avellanarius in the United Kingdom. I have assessed the effects of variation in habitat on hazel dormice at multiple spatial scales, and relate this to woodland management. I first introduce the status of and threats to wooded ecosystems, globally, across Europe and the UK. I look at how conservation approaches have evolved to address the negative effects on woodland biodiversity from changes in landscape and habitat configuration. -

Mammals List EN Alphabetical Aktuell

ETC® Species List Mammals © ETC® Organization Category Scientific Name English Name alphabetical M3 Addax nasomaculatus Addax M1 Ochotona rufescens Afghan Pika M1 Arvicanthis niloticus African Arvicanthis M1 Crocidura olivieri African Giant Shrew M3 Equus africanus African Wild Ass M1 Chiroptera (Order) all Bats and Flying Foxes M3 Rupicapra rupicapra (also R. pyrenaica) Alpine Chamois (also Pyrenean Chamois) M3 Capra ibex Alpine Ibex M2 Marmota marmota Alpine Marmot M1 Sorex alpinus Alpine Shrew M3 Ursus americanus American Black Bear M1 Neovison vison American Mink M3 Castor canadensis American/Canadian Beaver M2 Alopex lagopus Arctic Fox M3 Ovis ammon Argali M1 Sicista armenica Armenian Birch Mouse M1 Spermophilus xanthoprymnus Asia Minor Ground Squirrel M2 Meles leucurus Asian Badger M1 Suncus murinus Asian House Shrew M3 Equus hemionus Asiatic Wild Ass/Onager M3 Bos primigenius Aurochs M3 Axis axis Axis Deer M1 Spalax graecus Balkan Blind Mole Rat M1 Dinaromys bogdanovi Balkan Snow Vole M1 Myodes glareolus Bank Vole M1 Atlantoxerus getulus Barbary Ground Squirrel M1 Lemniscomys barbarus Barbary Lemniscomys M2 Macaca sylvanus Barbary Macaque, female M3 Macaca sylvanus Barbary Macaque, male M3 Ammotragus lervia Barbary Sheep M1 Barbastella barbastellus Barbastelle M1 Microtus bavaricus Bavarian Pine Vole M3 Erignathus barbatus Bearded Seal M1 Martes foina Beech Marten M1 Crocidura leucodon Bicolored White-toothed Shrew M1 Vulpes cana Blanford's Fox M2 Marmota bobak Bobak Marmot M2 Lynx rufus Bobcat M1 Mesocricetus brandtii Brandt's -

Factors Affecting Seed-Selection in the Hazel Dormouse

1 Acorns were good until tannins were found: factors affecting seed-selection 2 in the hazel dormouse (Muscardinus avellanarius) 3 Leonardo Ancillottoa,b, Giulia Sozioa, Alessio Mortellitiac* 4 5 aDepartment of Biology and Biotechnology “Charles Darwin”, University of Rome “La 6 Sapienza”, Viale dell’Università 32, 00185, Rome Italy. 7 b Wildlife Research Unit, Laboratorio di Ecologia Applicata, Dipartimento di Agraria, 8 Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II, Portici (Napoli), Italy 9 c Fenner School of Environment and Society, Australian Research Council Centre for 10 Environmental Decisions, National Environmental Research Program, The Australian 11 National University, Canberra, ACT 0200. Phone: T: +610261252737 12 13 *corresponding author: [email protected] 14 15 16 1 17 Abstract 18 Seed selection by forest rodents is based on several factors such as seed palatability, 19 manipulation time and caloric content. The final result of this decision-making process has 20 critical consequences on seed predation and dispersal, and thus on tree demography. 21 Previous studies on seed selection have mainly focused on non-hibernating terrestrial rodents. 22 Arboreal rodents may be less adapted to cope with seed defences, usually being more 23 frugivorous. Furthermore, hibernating species need to accumulate fat reserves in autumn, 24 which is when acorns are available and may be the only available resource. We selected the 25 hazel dormouse (Muscardinus avellanarius, an arboreal hibernating rodent) as model species 26 for our study and focused on three seeds which are an important constituent of the hazel 27 dormouse diet and which are characterized by different defensive strategies. 28 We here report the results of a series of experiments targeted towards understanding the 29 effects of manipulation time, energy intake and tannin content on seed selection by the hazel 30 dormouse and the effects of such selection on individuals' body condition.