ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: RE-EXAMINING VIOLA TRANSCRIPTIONS THROUGH INFORMED HISTORICAL PERFORMANCE Eva Mondragon, Doctor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue 189.Pmd

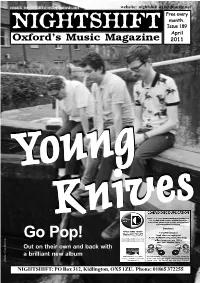

email: [email protected] NIGHTSHIFTwebsite: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every Oxford’s Music Magazine month. Issue 189 April 2011 YYYYYYoungoungoungoung KnivesKnivesKnivesKnives Go Pop! Out on their own and back with a brilliant new album photo: Cat Stevens NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net WILCO JOHNSON AND listings for the weekend, plus ticket DEACON BLUE are the latest details, are online at names added to this year’s www.oxfordjazzfestival.co.uk Cornbury Festival bill. The pair join already-announced headliners WITNEY MUSIC FESTIVAL returns James Blunt, The Faces and for its fifth annual run this month. Status Quo on a big-name bill that The festival runs from 24th April also includes Ray Davies, Cyndi through to 2nd May, featuring a Lauper, Bellowhead, Olly Murs, selection of mostly local acts across a GRUFF RHYS AND BELLOWHEAD have been announced as headliners The Like and Sophie Ellis-Bextor. dozen venues in the town. Amongst a at this year’s TRUCK FESTIVAL. Other new names on the bill are host of acts confirmed are Johnson For the first time Truck will run over three full days, over the weekend of prog-folksters Stackridge, Ben Smith and the Cadillac Blues Jam, 22nd-24th July at Hill Farm in Steventon. The festival will also enjoy an Montague & Pete Lawrie, Toy Phousa, Alice Messenger, Black Hats, increased capacity and the entire site has been redesigned to accommodate Hearts, Saint Jude and Jack Deer Chicago, Prohibition Smokers new stages. -

String Quartet in E Minor, Op 83

String Quartet in E minor, op 83 A quartet in three movements for two violins, viola and cello: 1 - Allegro moderato; 2 - Piacevole (poco andante); 3 - Allegro molto. Approximate Length: 30 minutes First Performance: Date: 21 May 1919 Venue: Wigmore Hall, London Performed by: Albert Sammons, W H Reed - violins; Raymond Jeremy - viola; Felix Salmond - cello Dedicated to: The Brodsky Quartet Elgar composed two part-quartets in 1878 and a complete one in 1887 but these were set aside and/or destroyed. Years later, the violinist Adolf Brodsky had been urging Elgar to compose a string quartet since 1900 when, as leader of the Hallé Orchestra, he performed several of Elgar's works. Consequently, Elgar first set about composing a String Quartet in 1907 after enjoying a concert in Malvern by the Brodsky Quartet. However, he put it aside when he embarked with determination on his long-delayed First Symphony. It appears that the composer subsequently used themes intended for this earlier quartet in other works, including the symphony. When he eventually returned to the genre, it was to compose an entirely fresh work. It was after enjoying an evening of chamber music in London with Billy Reed’s quartet, just before entering hospital for a tonsillitis operation, that Elgar decided on writing the quartet, and he began it whilst convalescing, completing the first movement by the end of March 1918. He composed that first movement at his home, Severn House, in Hampstead, depressed by the war news and debilitated from his operation. By May, he could move to the peaceful surroundings of Brinkwells, the country cottage that Lady Elgar had found for them in the depth of the Sussex countryside. -

Tertis's Viola Version of Elgar's Cello Concerto by Anthony Addison Special to Clevelandclassical

Preview Heights Chamber Orchestra conductor's notes: Tertis's viola version of Elgar's Cello Concerto by Anthony Addison Special to ClevelandClassical An old adage suggested that violists were merely vio- linists-in-decline. That was before Lionel Tertis! He was born in 1876 of musical parents who had come to England from Poland and Russia and, at three years old, he started playing the piano. At six he performed in public, but had to be locked in a room to make him practice, a procedure that has actually fostered many an international virtuoso. At thirteen, with the agree- ment of his parents, he left home to earn his living in music playing in pickup groups at summer resorts, accompanying a violinist, and acting as music attendant at a lunatic asylum. +41:J:-:/1?<1>95@@1041?@A0510-@(>5:5@E;88131;2!A?5/@-75:3B5;85:-?45? "second study," but concentrating on the piano and playing concertos with the school or- chestra. As sometime happens, his violin teacher showed little interest in a second study <A<58-:01B1:@;8045?2-@41>@4-@41C-?.1@@1>J@@102;>@413>;/1>E@>-01 +5@4?A/4 encouragement, Tertis decided he had to teach himself. Fate intervened when fellow stu- dents wanted to form a string quartet. Tertis volunteered to play viola, borrowed an in- strument, loved the rich quality of its lowest string and thereafter turned the old adage up- side down: a not very obviously gifted violinist becoming a world class violist. But, until the viola attained respectability in Tertis’s hands, composers were reluctant to write for the instrument. -

Jazz, Identity and Sound Design in a Melting Pot

ACADEMY OF MUSIC AND DRAMA Jazz, identity and sound design in a melting pot Lauri Kallio Independent Project (Degree Project), 15 HEC, Bachelor of Fine Arts in (Name of Program) Spring, 2019 Independent Project (Degree Project), 15 higher education credits Bachelor of Fine Arts in (Name of Program) Academy of Music and Drama, University of Gothenburg Spring, 2019 Author: Lauri Kallio Title: Jazz, identity and sound design in a melting pot Supervisor: Dr. Joel Eriksson Examiner: ABSTRACT In this piece of artistic research the author explores his musical toolbox and aesthetics for creating music. Finding compositional and music productional identity are also the main themes of this work. These aspects are being researched through the process creating new music. The author is also trying to build a bridge between his academic and informal studies over the years. The questions researched are about originality in composition and sound, and the challenges that occur during the working period. Key words: Jazz, Improvisation, Composition, Music Production, Ensemble, Free, Ambient 2 (34) Table of contents: 1. Introduction 1.1. Background 4 1.2. Goal and Questions 5 1.3. Method 6 2. Pre-recorded material 2.1.” 2147” 6 2.2. ”SAKIN” 7 2.3. ”BLE” 8 2.4. The selected elements 9 3. The compositions 3.1. “Mobile” 10 3.1.2. The rehearsing process 11 3.2. “ONEHE-274” 12 3.2.2. The rehearsing process 14 3.3. “TURBULENCE” 15 3.3.2. The rehearsing process 16 3.4. Rehearsing with electronics only 17 4. Conclusion 19 5. Afterword 20 6. -

The Seventh Season Being Mendelssohn CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL and INSTITUTE July 17–August 8, 2009 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors

The Seventh Season Being Mendelssohn CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL AND INSTITUTE July 17–August 8, 2009 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors Music@Menlo Being Mendelssohn the seventh season july 17–august 8, 2009 david finckel and wu han, artistic directors Contents 3 A Message from the Artistic Directors 5 Welcome from the Executive Director 7 Being Mendelssohn: Program Information 8 Essay: “Mendelssohn and Us” by R. Larry Todd 10 Encounters I–IV 12 Concert Programs I–V 29 Mendelssohn String Quartet Cycle I–III 35 Carte Blanche Concerts I–III 46 Chamber Music Institute 48 Prelude Performances 54 Koret Young Performers Concerts 57 Open House 58 Café Conversations 59 Master Classes 60 Visual Arts and the Festival 61 Artist and Faculty Biographies 74 Glossary 76 Join Music@Menlo 80 Acknowledgments 81 Ticket and Performance Information 83 Music@Menlo LIVE 84 Festival Calendar Cover artwork: untitled, 2009, oil on card stock, 40 x 40 cm by Theo Noll. Inside (p. 60): paintings by Theo Noll. Images on pp. 1, 7, 9 (Mendelssohn portrait), 10 (Mendelssohn portrait), 12, 16, 19, 23, and 26 courtesy of Bildarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz/Art Resource, NY. Images on pp. 10–11 (landscape) courtesy of Lebrecht Music and Arts; (insects, Mendelssohn on deathbed) courtesy of the Bridgeman Art Library. Photographs on pp. 30–31, Pacifica Quartet, courtesy of the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center. Theo Noll (p. 60): Simone Geissler. Bruce Adolphe (p. 61), Orli Shaham (p. 66), Da-Hong Seetoo (p. 83): Christian Steiner. William Bennett (p. 62): Ralph Granich. Hasse Borup (p. 62): Mary Noble Ours. -

Copyright and Use of This Thesis This Thesis Must Be Used in Accordance with the Provisions of the Copyright Act 1968

COPYRIGHT AND USE OF THIS THESIS This thesis must be used in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Reproduction of material protected by copyright may be an infringement of copyright and copyright owners may be entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. Section 51 (2) of the Copyright Act permits an authorized officer of a university library or archives to provide a copy (by communication or otherwise) of an unpublished thesis kept in the library or archives, to a person who satisfies the authorized officer that he or she requires the reproduction for the purposes of research or study. The Copyright Act grants the creator of a work a number of moral rights, specifically the right of attribution, the right against false attribution and the right of integrity. You may infringe the author’s moral rights if you: - fail to acknowledge the author of this thesis if you quote sections from the work - attribute this thesis to another author - subject this thesis to derogatory treatment which may prejudice the author’s reputation For further information contact the University’s Director of Copyright Services sydney.edu.au/copyright ALFRED HILL’S VIOLA CONCERTO: ANALYSIS, COMPOSITIONAL STYLE AND PERFORMANCE AESTHETIC Charlotte Fetherston A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Sydney Conservatorium of Music, University of Sydney, NSW 2014 STATEMENT OF ORIGINALITY ‘I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. -

The Search for Consistent Intonation: an Exploration and Guide for Violoncellists

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2017 THE SEARCH FOR CONSISTENT INTONATION: AN EXPLORATION AND GUIDE FOR VIOLONCELLISTS Daniel Hoppe University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2017.380 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Hoppe, Daniel, "THE SEARCH FOR CONSISTENT INTONATION: AN EXPLORATION AND GUIDE FOR VIOLONCELLISTS" (2017). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 98. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/98 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless an embargo applies. -

The Fourteenth Season: Russian Reflections July 15–August 6, 2016 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors Experience the Soothing Melody STAY with US

The Fourteenth Season: Russian Reflections July 15–August 6, 2016 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors Experience the soothing melody STAY WITH US Spacious modern comfortable rooms, complimentary Wi-Fi, 24-hour room service, fitness room and a large pool. Just two miles from Stanford. BOOK EVENT MEETING SPACE FOR 10 TO 700 GUESTS. CALL TO BOOK YOUR STAY TODAY: 650-857-0787 CABANAPALOALTO.COM DINE IN STYLE Chef Francis Ramirez’ cuisine centers around sourcing quality seasonal ingredients to create delectable dishes combining French techniques with a California flare! TRY OUR CHAMPAGNE SUNDAY BRUNCH RESERVATIONS: 650-628-0145 4290 EL CAMINO REAL PALO ALTO CALIFORNIA 94306 Music@Menlo Russian Reflections the fourteenth season July 15–August 6, 2016 D AVID FINCKEL AND WU HAN, ARTISTIC DIRECTORS Contents 2 Season Dedication 3 A Message from the Artistic Directors 4 Welcome from the Executive Director 4 Board, Administration, and Mission Statement 5 R ussian Reflections Program Overview 6 E ssay: “Natasha’s Dance: The Myth of Exotic Russia” by Orlando Figes 10 Encounters I–III 13 Concert Programs I–VII 43 Carte Blanche Concerts I–IV 58 Chamber Music Institute 60 Prelude Performances 67 Koret Young Performers Concerts 70 Master Classes 71 Café Conversations 72 2016 Visual Artist: Andrei Petrov 73 Music@Menlo LIVE 74 2016–2017 Winter Series 76 Artist and Faculty Biographies A dance lesson in the main hall of the Smolny Institute, St. Petersburg. Russian photographer, twentieth century. Private collection/Calmann and King Ltd./Bridgeman Images 88 Internship Program 90 Glossary 94 Join Music@Menlo 96 Acknowledgments 101 Ticket and Performance Information 103 Map and Directions 104 Calendar www.musicatmenlo.org 1 2016 Season Dedication Music@Menlo’s fourteenth season is dedicated to the following individuals and organizations that share the festival’s vision and whose tremendous support continues to make the realization of Music@Menlo’s mission possible. -

Great Violinists • Kreisler 8.111406

ADD Great Violinists • Kreisler 8.111406 THE COMPLETE recordinGs • 7 BACH BEETHOVEN KoŽeLUcH WAGNER dVořáK KreisLer Fritz Kreisler Recorded 1921-1925 Fritz Kreisler (1875-1962): Anton Rubinstein (1829-1894): Leopold Antonín Koželuch (1747-1818) Deux Mélodies, Op. 3 (att. Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)): The complete recordings • 7 ^ No. 1: Moderato assai in F major 2:50 La ritrovata figlia di ottone ii rec. 1st November 1923; ™ Gavotte in F, (arr. A. Walter Kramer) 2:54 mat. Bb-3779; Victor 1039 rec. 29th August 1925; Acoustic Recordings Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827): mat. BVE-31975-4; Victor 1136 HMV Acoustic Recordings 8 Andante favori in F, Woo 57 (arr. Kreisler) 3:08 Jean Gabriel Prosper Marie (1852-1928): & (Hayes, Middlesex, 1921-24) rec. 23rd September 1924; La Cinquantaine (The Golden Wedding) 2:50 Johann sebastian Bach (1685-1750) mat. Bb-3778-7; Victor 3037 rec. 1st November 1923; Wilhelm Jeral (1861-1935): Anna Magdalena notebook 1 Sérénade viennoise, Op. 18 3:19 Robert Schumann (1810-1856): mat. Bb-3781; Victor 1039 £ Minuet in G, BWV Anh. 116 rec. 16th December 1921; Klavierstücke, op. 85 (doubtful attribution, arr. Winternitz) 2:53 mat. Bb-779-3; Victor 87579 9 No. 12 Abendlied (arr. Svendsen) 2:18 Electrical Recordings rec. 29th August 1925; rec. 23rd September 1924; Victor Talking Machine company mat. BVE-31940-12; Victor 1136 Traditional: mat. Bb-5102-6; Victor 3036 (new York, 1925-26) 2 Londonderry Air (arr. Kreisler) 3:20 sigmund romberg (1887-1951) rec. 17th December 1921; Fritz Kreisler: Fritz Kreisler: The Student Prince – Operetta ¢ mat. Bb-780-5; Victor 87577 Apple Blossoms – Operetta * Paraphrase on two russian folk songs 3:09 Deep in my heart, dear (arr. -

An Obscure History of the Guitar Or, a History of Obscure Guitars Franklin Lei, Vihuela, Early Viennese Guitar, Archtop Guitar

A 2016 Berkeley Festival Fringe event sponsored by Trinity Chamber Concerts An Obscure History of the Guitar or, A History of Obscure Guitars Trinity Chapel, 2320 Dana Street Saturday June 11th, 2016, 10:30 a.m. Franklin Lei, vihuela, early Viennese guitar, archtop guitar I. Ricercar 84 – Fantasia 40 – Fantasia 30 – Ricercar 16 - Francesco Canova da Milano (1497-1543) Tochata – Ricercar 34, ‘La compagna’ II. Diferencias sobre ‘Guárdame las vcas’ (both sets) Luys de Narváez (c.1505-1549) Fantasia V Luis Milán (c.1500-1561) Fantasia que contrahaze la harpa en la manera de Luduvico Alonso Mudarra (c.1510-1580) III. Grande Ouverture, Opus 61 : Mauro Giuliani, 1781-1829 Andante Sostenuto – Allegro Maestoso Source: Facsimile of the First Edition by Giovanni Ricordi, Milan, late 1814 IV. Blues in the Night Harold Arlen (1905-1986) Autumn in New York Vernon Duke (1903-1969) Night and Day Cole Porter (1891-1964) Here’s That Rainy Day Jimmy Van Heusen (1913-1990) Letter to Evan* - Laurie* Bill Evans (1929-1980) Arrangements by Franklin Lei (except * by Sid Jacobs) 6-course Vihuela: Daniel Larson, Duluth MN, 1997 (after iconographic sources especially Juan Bermudo’s woodcut) Viennese guitar: Johann Michael Rudert, Vienna, dated 1811 Acoustic archtop: Tom Bills, St. Louis, 2013 An obscure history of the guitar or, A history of obscure guitars I am playing three guitars from very different periods in the instrument’s history: The vihuela de mano dates from most of the 16th century. Strung in courses (pairs of strings) and tuned as the Renaissance lute, the vihuela is the true ancestor of the modern guitar. -

Nycemf 2021 Program Book

NEW YORK CITY ELECTROACOUSTIC MUSIC FESTIVAL __ VIRTUAL ONLINE FESTIVAL __ www.nycemf.org CONTENTS DIRECTOR’S WELCOME 3 STEERING COMMITTEE 3 REVIEWING 6 PAPERS 7 WORKSHOPS 9 CONCERTS 10 INSTALLATIONS 51 BIOGRAPHIES 53 DIRECTOR’S NYCEMF 2021 WELCOME STEERING COMMITTEE Welcome to NYCEMF 2021. After a year of having Ioannis Andriotis, composer and audio engineer. virtually all live music in New York City and elsewhere https://www.andriotismusic.com/ completely shut down due to the coronavirus pandemic, we decided that we still wanted to provide an outlet to all Angelo Bello, composer. https://angelobello.net the composers who have continued to write music during this time. That is why we decided to plan another virtual Nathan Bowen, composer, Professor at Moorpark electroacoustic music festival for this year. Last year, College (http://nb23.com/blog/) after having planned a live festival, we had to cancel it and put on everything virtually; this year, we planned to George Brunner, composer, Director of Music go virtual from the start. We hope to be able to resume Technology, Brooklyn College C.U.N.Y. our live concerts in 2022. Daniel Fine, composer, New York City The limitations of a virtual festival meant that we could plan only to do events that could be done through the Travis Garrison, composer, Music Technology faculty at internet. Only stereo music could be played, and only the University of Central Missouri online installations could work. Paper sessions and (http://www.travisgarrison.com) workshops could be done through applications like zoom. We hope to be able to do all of these things in Doug Geers, composer, Professor of Music at Brooklyn person next year, and to resume concerts in full surround College sound. -

Virus Infects 200 Notre Dame Students

.------------- ---- Tuesdav, December 3, 2002 Trojans ,I THE spoil ND's holiday Insider The Independent Newspaper Serving Notre Dame and Saint Mary's VOL XXXV.II NO. 66 HTTP://OBSERVER.ND.EDU Virus infects 200 Notre Dame students is highly contagious," said Matt "The overnight census is up," order to prevent a campus out After vomiting begins. Brubaker By COLLEEN GANEY Starin, vice president of according to Pat Brubaker, assis break. Lodging several infected said, "The best thing is to give the N~sWritcr Communications at Notre Dame. tant director of University Health patients could have spread it to guts a vacation for two to four The virus thrives in closed com Services. students visiting Health Services hours." An unnamed gastrointestinal munities like a The infir for other reasons. During this time, people virus infected over 200 Notre college campus. "If mary usually "If students share air or share shouldn't ingest any food or liq Dame students in the past 10 It has also students share air or has three to spit, the virus is going to get uids, including water. days. according to Notre Dame affected South spit. the virus is going to four overnight passed," Brubaker said, specifYing They should then consume clear llealth Services. Bend schools get passed. " patients suffer that drinking glasses, doorknobs liquids. Powerade and Popsicles Symptoms include nausea, vom and Channel16 ing from the and keyboards are convenient are good options. he said, but not iting. a low-grade fever and diar employees, disease during modes of transfer. milk or orange juice. rhea, but should not be confused which may Pat Brubaker the week She emphasizes that hand Brubaker said that people with influenza, which is an upper explain their assistant director of before washing is the best way to ward should seek assistance if they respiratory virus marked by coverage of it University Health Services Thanksgiving, off the disease.