Pcaaa857.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POPCEN Report No. 3.Pdf

CITATION: Philippine Statistics Authority, 2015 Census of Population, Report No. 3 – Population, Land Area, and Population Density ISSN 0117-1453 ISSN 0117-1453 REPORT NO. 3 22001155 CCeennssuuss ooff PPooppuullaattiioonn PPooppuullaattiioonn,, LLaanndd AArreeaa,, aanndd PPooppuullaattiioonn DDeennssiittyy Republic of the Philippines Philippine Statistics Authority Quezon City REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES HIS EXCELLENCY PRESIDENT RODRIGO R. DUTERTE PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY BOARD Honorable Ernesto M. Pernia Chairperson PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY Lisa Grace S. Bersales, Ph.D. National Statistician Josie B. Perez Deputy National Statistician Censuses and Technical Coordination Office Minerva Eloisa P. Esquivias Assistant National Statistician National Censuses Service ISSN 0117-1453 FOREWORD The Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) conducted the 2015 Census of Population (POPCEN 2015) in August 2015 primarily to update the country’s population and its demographic characteristics, such as the size, composition, and geographic distribution. Report No. 3 – Population, Land Area, and Population Density is among the series of publications that present the results of the POPCEN 2015. This publication provides information on the population size, land area, and population density by region, province, highly urbanized city, and city/municipality based on the data from population census conducted by the PSA in the years 2000, 2010, and 2015; and data on land area by city/municipality as of December 2013 that was provided by the Land Management Bureau (LMB) of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR). Also presented in this report is the percent change in the population density over the three census years. The population density shows the relationship of the population to the size of land where the population resides. -

PALMA+PB Alliance of Municipalities

PALMA+PB Alliance of Municipalities Province of Cotabato Region X11 PALMA+PB is an acronym DERIVED FROM the first letter of the names of the municipalities that comprise the Alliance, namely: Pigcawayan Alamada Libungan Midsayap Aleosan Pikit Banisilan Pikit became a member of the alliance only last April 25, 2008 and Banisilan in August 18,2011 after one (1) year of probation as observer . PALMA+PB Alliance Luzon Alamada Banisilan Pigcawayan Visayas Libungan Aleosan Midsayap Mindanao Pikit Located in the first congressional district of Cotabato Province, Region XII in the island of Mindanao, Philippines. PALMA+PB Alliance THE CREATION OF PALMA+PB Alliance The establishment of this Alliance gets its legal basis from REPUBLIC ACT 7160 “THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT CODE OF 1991, Section 33, Art. 3, Chapter 3, which states that; “LGUs may, through appropriate ordinances, group themselves, consolidate, or ordinate their efforts, services, and resources for purposes commonly beneficial to them. In support to such undertakings, the LGUs involved may, upon approval by the Sanggunian concerned after a public hearing conducted for the purpose, contribute funds, real estate, equipment and other kinds of property and appoint or assign, personnel under such terms and conditions as may be agreed upon by the participating local units through Memoranda of Agreement (MOA).” PALMA+PB Alliance Profile Land Area :280,015.88 has. Population :393,831 Population Density :1.41 person/ha. Population by Tribe: Cebuano :30.18% Maguindanaon :25.45% Ilonggo :19.82% Ilocano :11.15% IP’s :10.55% Other Tribes :2.85% Number of Barangays :215 Number of Households :81,767 Basic Products Agricultural and Fresh Water fish PALMA+PB Alliance B. -

NORTH COTABATO (In P0.00 )

Annex 1 LBM No. 61 CY 2009 FINAL INTERNAL REVENUE ALLOTMENT FOR BARANGAYS REGION XII PROVINCE OF NORTH COTABATO (In P0.00 ) BARANGAY TOTAL 01 MUNICIPALITY OF ALAMADA 1 Bao 2,400,680.00 2 Barangiran 1,668,634.00 3 Camansi 965,004.00 4 Dado 2,925,158.00 5 Guiling 1,756,356.00 6 Kitacubong (Pob.) 2,026,317.00 7 Macabasa 945,545.00 8 Malitubog 1,265,854.00 9 Mapurok 1,192,031.00 10 Mirasol 915,583.00 11 Pacao 1,071,568.00 12 Paruayan 1,272,958.00 13 Pigcawaran 1,870,950.00 14 Polayagan 1,234,966.00 15 Rangayen 1,259,367.00 16 Raradangan 1,038,827.00 ----------------------- Total 23,809,798.00 ============== 02 MUNICIPALITY OF ALEOSAN 1 Bagolibas 836,819.00 2 Cawilihan 874,502.00 3 Dualing 1,319,599.00 4 Dunguan 1,125,622.00 5 Katalicanan 820,139.00 6 Lawili 942,456.00 7 Lower Mingading 825,699.00 8 Luanan 807,166.00 9 Malapang 888,093.00 10 New Leon 1,130,255.00 11 New Panay 1,248,247.00 12 Pagangan 1,379,830.00 13 Palacat 721,607.00 14 Pentil 918,672.00 15 San Mateo 1,782,610.00 CY 2009 FINAL INTERNAL REVENUE ALLOTMENT FOR BARANGAYS REGION XII PROVINCE OF NORTH COTABATO (In P0.00 ) BARANGAY TOTAL 16 Santa Cruz 800,062.00 17 Tapodoc 982,919.00 18 Tomado 1,296,742.00 19 Upper Mingading 1,202,224.00 ----------------------- Total 19,903,263.00 ============== 03 MUNICIPALITY OF ANTIPAS 1 Camutan 1,112,958.00 2 Canaan 745,081.00 3 Dolores 795,120.00 4 Kiyaab 1,130,255.00 5 Luhong 859,367.00 6 Magsaysay 954,811.00 7 Malangag 817,977.00 8 Malatad 1,451,800.00 9 Malire 979,522.00 10 New Pontevedra 926,085.00 11 Poblacion 2,374,425.00 12 B. -

One Big File

MISSING TARGETS An alternative MDG midterm report NOVEMBER 2007 Missing Targets: An Alternative MDG Midterm Report Social Watch Philippines 2007 Report Copyright 2007 ISSN: 1656-9490 2007 Report Team Isagani R. Serrano, Editor Rene R. Raya, Co-editor Janet R. Carandang, Coordinator Maria Luz R. Anigan, Research Associate Nadja B. Ginete, Research Assistant Rebecca S. Gaddi, Gender Specialist Paul Escober, Data Analyst Joann M. Divinagracia, Data Analyst Lourdes Fernandez, Copy Editor Nanie Gonzales, Lay-out Artist Benjo Laygo, Cover Design Contributors Isagani R. Serrano Ma. Victoria R. Raquiza Rene R. Raya Merci L. Fabros Jonathan D. Ronquillo Rachel O. Morala Jessica Dator-Bercilla Victoria Tauli Corpuz Eduardo Gonzalez Shubert L. Ciencia Magdalena C. Monge Dante O. Bismonte Emilio Paz Roy Layoza Gay D. Defiesta Joseph Gloria This book was made possible with full support of Oxfam Novib. Printed in the Philippines CO N T EN T S Key to Acronyms .............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. iv Foreword.................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... vii The MDGs and Social Watch -

REPUBLICOF the PHILIPPINES Joint Memorandum Circular No. 01, Series of 2010 06 August 2010 TO

dti OE~A"rM("T OF TRAot: AND IJCOUSTlfY "HIll"PI,.rS REPUBLICOF THE PHILIPPINES Joint Memorandum Circular No. 01, Series of 2010 06 August 2010 TO: THE REGIONAL AND PROVINCIAL DIRECTORS OF THE DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT (DILG) AND THE DEPARTMENT OF TRADE AND INDUSTRY (DTI), THE BUREAU OF FIRE PROTECTION (BFP) AND MEMBERS OF THE SANGGUNIANG PANGLUNGSOD AND SANGGUNIANG BAYAN SUBJECT: GUIDELINES IN IMPLEMENTING THE STANDARDS IN PROCESSING BUSINESS PERMITS AND LICENSESIN ALL CITIESAND MUNICIPALITIES 1.0 Purpose 1.1 To disseminate the service standards in processing business permits and licenses which cities and municipalities are enjoined to follow; 1.2 To provide the guidelines for streamlining the business permits and licensing systems (BPLS) in cities and municipalities in accordance with the service standards which the national government is setting consistent with Republic Act No. 9485, otherwise known as the Anti-Red Tape Act of 2007 (ARTA); 1.3 To clarify the roles and responsibilities of the Department of the Interior and Local Government (DILG), the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI), and the various cities and municipalities in the country in ensuring the implementation of the BPLSstandards. 2.0 Statement of Policies 2.1 The government recognizes the importance of improving the country's growth potential through enhancing its competitiveness at the national and local levels. This can only be achieved through reforms that reduce the cost of doing business in the country and address the other policy issues that discourage international and local investors. 2.2 Pursuant to Republic Act No. 9485, all government instrumentalities and local government units are mandated to provide efficient delivery of services to the public by reducing bureaucratic red tape and preventing graft and corruption, and providing penalties thereof. -

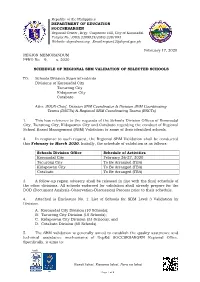

DEPARTMENT of EDUCATION SOCCSKSARGEN February 17, 2020 REGION MEMORANDUM PPRD No. 9, S. 2020 SCHEDULE of REGION

Republic of the Philippines DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION SOCCSKSARGEN Regional Center, Brgy. Carpenter Hill, City of Koronadal Telefax No.: (083) 2288825/(083) 2281893 Website: depedroxii.org Email:[email protected] February 17, 2020 REGION MEMORANDUM PPRD No. 9, s. 2020 SCHEDULE OF REGIONAL SBM VALIDATION OF SELECTED SCHOOLS TO: Schools Division Superintendents Divisions of Koronadal City Tacurong City Kidapawan City Cotabato Attn: SGOD Chief, Division SBM Coordinator & Division SBM Coordinating Teams (DSCTs) & Regional SBM Coordinating Teams (RSCTs) 1. This has reference to the requests of the Schools Division Offices of Koronadal City, Tacurong City, Kidapawan City and Cotabato regarding the conduct of Regional School-Based Management (SBM) Validation to some of their identified schools. 2. In response to such request, the Regional SBM Validation shall be conducted this February to March 2020. Initially, the schedule of validation is as follows: Schools Division Office Schedule of Activities Koronadal City February 26-27, 2020 Tacurong City To Be Arranged (TBA) Kidapawan City To Be Arranged (TBA) Cotabato To Be Arranged (TBA) 3. A follow-up region advisory shall be released in line with the final schedule of the other divisions. All schools endorsed for validation shall already prepare for the DOD (Document Analysis-Observation-Discussion) Process prior to their schedule. 4. Attached is Enclosure No. 1: List of Schools for SBM Level 3 Validation by Division. A. Koronadal City Division (10 Schools); B. Tacurong City Division (10 Schools); C. Kidapawan City Division (33 Schools); and D. Cotabato Division (60 Schools). 5. The SBM validation is generally aimed to establish the quality assurance and technical assistance mechanisms of DepEd SOCCSKSARGEN Regional Office. -

Republic of the Philippines Department of Public Works and Highways Cotabato Second District Engineering Office Villarica, Midsayap, Cotabato

Republic of the Philippines Department of Public Works and Highways Cotabato Second District Engineering Office Villarica, Midsayap, Cotabato INDICATIVE ANNUAL PROCUREMENT PLAN FY 2020 CIVIL WORKS AND GOODS AND SERVICES Procurement PMO/ Is This an Early Mode of Schedule for Each Procurement Activity Estimated Budget (PhP) Remarks Procurement Activity Procurement Advertisement/ Submission/ Notice of Contract Source of Total Brief Description of Program/Project EndSection -User (Yes/No) Bidding Posting01/04/2018 of IB/REI Opening of Bids Award Signing Funds ('000) MOOE CO Program/Project Midsayap-Makar Rd - K1696 + 820 - 10/01-07/2019 10/21/2019 01/13/2020 01/20/2020 1.0 K1698 + 066.30 Const. Section Yes Public Bidding NEP 2020 40.434 Asphalt Overlay Banisilan-Guiling-Alamada-Libungan Rd - K1640 + 500 - K1640 + 1000, K1642 + 10/01-07/2019 10/21/2019 01/13/2020 01/20/2020 036 - K1642 + 114, K1643 + 000 - K1645 2.0 + 062 Const. Section Yes Public Bidding NEP 2020 41.542 Asphalt Overlay Dualing-Baliki-Silik Road - K1695+000 - 3.0 K1699+002 (Baliki-Dungguan-Langayen Public Bidding 10/01-07/2019 10/21/2019 01/13/2020 01/20/2020 43.249 Section) Const. Section Yes NEP 2020 Asphalt Overlay Dualing-New Panay-Midsayap Road - K1707+000 - K1709+000, K1710+000 - Public Bidding 10/01-07/2019 10/21/2019 01/13/2020 01/20/2020 4.0 K1712+075 (New Panay - Lawili Section) Const. Section Yes NEP 2020 42.754 Asphalt Overlay Midsayap-Makar Road - K1694+(- Public Bidding 10/01-07/2019 10/21/2019 01/13/2020 01/20/2020 Widening 5.0 269.50) - K1694+980 (Midsayap Section) Const. -

Municipal Profile

MUNICIPAL PROFILE HOW THE MUNICIPALITY OF WAO GOT ITS NAME FROM THE LEGEND It was told that many years ago a Bai Sa Raya, a beautiful Muslim princess from a kingdom in Cotawato (now Cotabato),in the island of Mindanao, visited the place now called “Wao”. It was a coincidence that during her visit there was severe drought in the area; “Kawaw” or “Uhaw” meaning, “I am thirsty” in English. From then on, the inhabitants in this area called the place “Wao”, a word phonetically derived from the word “Kawaw” or “Uhaw”, in commemoration of the sad experience of the Muslim princess. FROM THE NAME OF A CREEK Before the arrival of the Christian farmer-settlers in Wao in 1954, there used to be a creek called “Wao” within the Barangay Eastern Wao. The informant is Pastor Misuari Saripada, a church minister of the Seventh Day Adventist Church of Wao. The creek runs from the present Wao Central Market down to the farm lot of Felipe Daguino. Sultan Solaiman Amad, the present Municipal Assessor of Wao and Barangay Councilman Benito Masid, a respectable sultan in Muslim Village, corroborated the name of the creek. The writer verified the existence of this creek on March 2, 1991. FROM THE WORD “LIAWAO” The third version may be hypothetical but there is a strong reason to believe that the name “Wao” may have been also derived from the Maranaw word “Liawao”, meaning, “a place located above” in English. The present poblacion that bears the same name of the municipality used to be a Muslim community during the pre-settlement days. -

Philippine Rubber Industry Roadmap 2017-2022

PHILIPPINE RUBBER INDUSTRY ROADMAP 2017-2022 i FOREWORD he Department of Trade and Industry and the Department of Agriculture have been since 2012 spearheading the formulation of Philippine Rubber Industry Roadmap. In 2012, both agencies did parallel initiatives by outsourcing the T preparation of the rubber industry development plans to the University of the Asia and the Pacific (UA&P) for the upstream sector and the University of the Philippines – Institute for Small Scale Industries (UP-ISSI) for the downstream sector. In the same year, the Department of Science and Technology came out with its Rubber Research and Development Agenda manifesting the agency’s strong support in the development of the rubber industry. The DOST’s Rubber R&D Agenda was integrated in the annual Rubber Industry Cluster Action Plan since 2012. The two (2) development plans were used by the Philippine Rubber Technical Working Group (PHLRUBBER TWG) as basis in the preparation and implementation of an annual Rubber Industry Cluster Action Plan (Rubber InCup) starting 2013 until 2015. It was in 2013 that the PHLRUBBER decided to integrate the two (2) industry development plans. After series of consultations and workshops, the integration was finalized in 2015 resulting to the crafting of the Philippine Rubber Industry Roadmap 2016-2022. By consolidating the roadmaps, all agencies allied to the development of the rubber industry are expected to work on the same vision, goals and objectives and harmonize all programs and projects designed to improve the growth of the industry as well as its contribution in poverty reduction most particularly among smallholders. -

Sultan Kudarat Hon

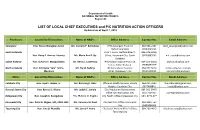

=lDepartment of Health NATIONAL NUTRITION COUNCIL Region XII LIST OF LOCAL CHIEF EXECUTIVES and P/C NUTRITION ACTION OFFICERS Updated as of January 7, 2019 Provinces Local Chief Executives Name of NAO’s Office Address Contact No. Email Address Sarangani Hon. Steve Chiongbian-Solon Dr. Arvin C. Alejandro IPHO-Sarangani Province 083-508-2167 [email protected] Alabel, Sarangani 09393045621 South Cotabato Prov’ l. Social Welfare &Dev’t. 083-228-2184/ Hon. Daisy P. Avance- Fuentes Ms. Maria Ana D. Uy Office, Koronadal City, South 09266885635 [email protected] Cotabato Sultan Kudarat Hon. Datu Pax Mangudadatu Dr. Consolacion Lagamayo IPHO-Sultan Kudarat Province, 064-201-3032 [email protected] Isulan, Sultan Kudarat North Cotabato Hon. Emmylou ”Lala” Taliño- Mr. Ely M. Nebrija IPHO-Cotabato Province 064-572-5014 [email protected] Mendoza Amas, Kidapawan City 09090001911 [email protected] Cities Local Chief Executives Name of NAO’s Office Address Contact No. Email Address Cotabato City Hon. Frances Cynthia Guiani- Ms. Bai linang C. Abas Office on Health Services, 064-421-3140 [email protected] Sayadi Rosary Heights, Cotabato City 09161068896 [email protected] General Santos City Hon. Ronnel C. Rivera Dr. Rochelle G. Oco, MD, City Health Office, General 09427529747 MCHA Santos City Kidapawan City Hon. Joseph A. Evangelista Ms. Melanie S. Espina City Nutrition Office, 064- 5771-377/ Kidapawan City 09482370612 [email protected] Koronadal City Hon. Peter B. Miguel, MD, FPSO- Ms. Veronica M. Daut City Nutrition Office, Koronadal 083-228-1763 HNS City 09498494864 Tacurong City Hon. Lina O. Montilla N/A City Social Welfare & Dev’t 064-200-4915 [email protected] Office, Tacurong City 09296096884 List of Local Chief Executives & Municipal Nutrition Action Officers (SOUTH COTABATO) Municipality Mayor Name of NAO’s Office Address Contact No. -

LIST of LOCAL CHIEF EXECUTIVES and P/C NUTRITION ACTION OFFICERS Updated As of April 7, 2016

Department of Health NATIONAL NUTRITION COUNCIL Region XII LIST OF LOCAL CHIEF EXECUTIVES and P/C NUTRITION ACTION OFFICERS Updated as of April 7, 2016 Provinces Local Chief Executives Name of NAO’s Office Address Contact No. Email Address Sarangani Hon. Steve Chiongbian-Solon Ms. Cornelia P. Baldelovar IPHO-Sarangani Province 083-508-2167 [email protected] Alabel, Sarangani 09393045621 South Cotabato Prov’ l. Social Welfare &Dev’t. 083-228-2184/ Hon. Daisy P. Avance- Fuentes Ms. Maria Ana D. Uy Office, Koronadal City, South 09266885635 [email protected] Cotabato Sultan Kudarat Hon. Suharto T. Mangudadatu Dr. Henry L. Lastimoso IPHO-Sultan Kudarat Province, 064-201-3032/ [email protected] Isulan, Sultan Kudarat 09088490729 North Cotabato Hon. Emmylou ”Lala” Taliño- Mr. Ely M. Nebrija IPHO-Cotabato Province 064-572-5014 [email protected] Mendoza Amas, Kidapawan City 09155119911 [email protected] Cities Local Chief Executives Name of NAO’s Office Address Contact No. Email Address Cotabato City Hon. Japal J. Guiani, Jr. Ms. BailinangC. Abas Office on Health Services, Rosary 064-421-3140 [email protected] Heights, Cotabato City 0917448816 [email protected] General Santos City Hon. Ronnel C. Rivera Ms. Judith C. Janiola City Population Management 083-302-3947/ Office, General Santos City 09177314457 [email protected] Kidapawan City Hon. Joseph A. Evangelista Ms. Melanie S. Espina City Health Office, Kidapawan City 064- 5771-377 Koronadal City Hon. Peter B. Miguel, MD, FPSO-HNS Ms. Veronica M. Daut City Nutrition Office, Koronadal 083-228-1763 City 09498494864 Tacurong City Hon. Lina O. Montilla Ms. Lorna P. Pama City Social Welfare &Dev’t Office, 064-200-4915 [email protected] Tacurong City List of Local Chief Executives & Municipal Nutrition Action Officers (SOUTH COTABATO) Municipality Mayor Name of NAO’s Office Address Contact No. -

North-Cotabato-Ph-Corn.Pdf

124°20' 124°30' 124°40' 124°50' 125° 125°10' 125°20' 7°40' 7°40' R E P U B L I C O F T H E P H I L I P P I N E S DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE Province of Lanao del Sur BUREAU OF SOILS AND WATER MANAGEMENT Elliptical Road Cor. Visayas Ave., Diliman, Quezon City SOIL pH MAP ( Key Corn Areas ) PROVINCE OF NORTH COTABATO ° SCALE 1:130,000 0 2 4 6 8 10 Kilometers Projection : Transverse Mercator Banisilan ! Datum : PRS 1992 7°30' DISCLAIMER : All political boundaries are not authoritative 7°30' Province of Bukidnon Province of Maguindanao Alamada ! Arakan ! 7°20' Province of Davao del Sur 7°20' Libungan ! Pigcawayan ! Antipas ! !Carmen !Midsayap 7°10' 7°10' !Aleosan !President Roxas Kabacan ! Province of Maguindanao Magpet Matalam ! ! Pikit ! LOCATION MAP Kidapawan \ 7° 7° Lanao Del Sur 20°0' Bukidnon LUZON 15°0' Province of Maguindanao !Makilala NORTH COTABATO !M'lang 7°0' VISAYAS 10°0' Maguindanao Davao Del Sur Sultan MINDANAO Kudarat 5°0' LEGEND South Cotabato 125°0' 120°0' 125°0' pH Value GENERAL AREA MAPPING UNIT DESCRIPTION (1:1 Ratio) RATING ha % Nearly Neutral to CONVENTIONAL SIGNS 6.9 and above; !Bagontapay Low Extremely Alkaline, 1,914 11.84 4.5 and below Province of Davao del Sur ROADS BOUNDARY HYDROLOGY Extremely Acid Expressway Regional Rivers / Lake 4.6 - 5.0 Moderately Low Very Strongly Acid 57 0.35 Trunk line Provincial Shoreline Primary City PLACES 5.1 - 5.5 Moderately High Strongly Acid 2,079 12.86 Secondary Municipal \ ^ Capital City / City Tulunan 6°50' Tertiary Moderately Acid ! 6°50' P ! Capital Town / Town 5.6 - 6.8 High 12,122 74.95 Residential to Slightly Acid TOTAL 16,172 100.00 Area estimated based on actual field survey, other information from DA-RFO's, MA's, NAMRIA Land Cover (2010) and BSWM Land Use MISCELLANEOUS INFORMATION System Map.