Shua B. Freeman Working-Class New York Also by Joshua B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dooley Dispatch

The Dooley Dispatch November 2019 Celebrating 40 years of Friendship, Unity, and Christian Charity Editor – Pat Shea 804.516.9598 ([email protected]) Photographer – Patrick Shea ([email protected]) Webmaster – Patrick Shea ([email protected]) Webpage http://aohrichmond.org Check out the web page for better pictures, events, green pages, various reports Chaplain Next Meeting – Tuesday November 12, 2019 7:00 p.m. St. Michael Church Fr. George Zahn President’s Message: President Steve McGann 651-3960 Brothers, [email protected] Vice President First off and on the behalf of the Division, Thank You to all Mike Canning 690-0338 those who served in our nation’s Armed Forces. May God [email protected] bless you and forever hold you in the palm of His hands. Recording Secretary John Condon 980-5649 Once again we head into our favorite season of the year – our [email protected] raffle sales season! We started with a grand Division turnout Financial Secretary for our “Trip to Ireland” raffle sales at the Central Virginia Celtic Festival and John Costello 920-1796 Highland Games on October 26 – 27. Thanks again to our chairman Jim Woods [email protected] and all the brothers who participated. We had good weather both days, though Treasurer Sunday morning rains delayed us a bit. We were joined again by the lovely ladies Patrick Knightly 687-3868 of the LAOH, who no doubt improved the overall looks of the tent and those [email protected] gathered therein. Special thanks to the lads from St Patrick’s tent who made sure Chairman of Standing we had a steady supply of medicinal spirits. -

Connolly in America: the Political Development of an Irish Marxist As Seen from His Writings and His Involvement with the American Socialist Movement 1902-1910

THESIS UNIVERSITY OF NEW HAMPSHIRE JAMES CONNOLLY IN AMERICA: THE POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT OF AN IRISH MARXIST AS SEEN FROM HIS WRITINGS AND HIS INVOLVEMENT WITH THE AMERICAN SOCIALIST MOVEMENT 1902-1910 by MICHEÁL MANUS O’RIORDAN MASTER OF ARTS 1971 A 2009 INTRODUCTION I have been most fortunate in life as regards both educational opportunities and career choice. I say this as a preface to explaining how I came to be a student in the USA 1969-1971, and a student not only of the history of James Connolly’s life in the New World a century ago, but also a witness of, and participant in, some of the most momentous developments in the living history of the US anti-war and social and labour movements of 40 years ago. I was born on Dublin’s South Circular Road in May 1949, to Kay Keohane [1910-1991] and her husband Micheál O’Riordan [1917- 2006], an ITGWU bus worker. This was an era that preceded not only free third-level education, but free second-level education as well. My primary education was received in St. Kevin’s National School, Grantham Street, and Christian Brothers’ School, Synge Street. Driven to study - and not always willingly! - by a mother who passionately believed in the principle expounded by Young Irelander Thomas Davis – “Educate, that you may be free!” - I was fortunate enough to achieve exam success in 1961 in winning a Dublin Corporation secondary school scholarship. By covering my fees, this enabled me to continue with second-level education at Synge Street. In my 1966 Leaving Certificate exams I was also fortunate to win a Dublin Corporation university scholarship. -

How Labor Won and Lost the Public in Postwar America, 1947-1959

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2014 The Fight Over John Q: How Labor Won and Lost the Public in Postwar America, 1947-1959 Rachel Burstein Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/179 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] The Fight Over John Q: How Labor Won and Lost the Public in Postwar America, 1947-1959 by Rachel Burstein A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2014 © 2014 Rachel Burstein All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. __________________ _______________________________________ Date Joshua Freeman, Chair of Examining Committee __________________ _______________________________________ Date Helena Rosenblatt, Executive Officer Joshua Brown Thomas Kessner David Nasaw Clarence Taylor Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract The Fight Over John Q: How Labor Won and Lost the Public in Postwar America, 1947-1959 by Rachel Burstein Adviser: Joshua Freeman This study examines the infancy of large-scale, coordinated public relations by organized labor in the postwar period. Labor leaders’ outreach to diverse publics became a key feature of unions’ growing political involvement and marked a departure from the past when unions used organized workers – not the larger public – to pressure legislators. -

Syndicalism's Legacy and Left Labor Strategy Today

Syndicalism’s Legacy and Left Labor Strategy Today In Western Europe, revolutionary syndicalism … was the direct and inevitable result of opportunism, reformism, and parliamentary cretinism (in the socialist movement). —Lenin Between the 1848 publication of the Communist Manifesto and the beginning of the twentieth century, socialists achieved mass working-class influence in the rich countries by building allied unions and political parties. But in the first two decades of the twentieth century, dissident revolutionaries built a rival tradition—the syndicalist movement. “Syndicalism,” an alternative term for “unionism,” reacted against the growing bureaucratic conservatism (and sometimes betrayals) of the socialist organizations. It stood for class struggle, direct action, workers’ control, rank and file democracy, internationalism, and revolution. Believing that working-class gains up to and including revolution required unionization as their weapon and striking (up to the general strike) as their tactic, syndicalists rejected political parties as worse than useless. This fit nicely for anarchists, whose influence resurged as “anarcho-syndicalism.” For others, syndicalism aligned with a return to the core Marxist concepts of working-class self-activity and self-emancipation. Syndicalist union federations prospered in Mexico, Ireland, Italy, Spain, and France. Though the movement was devastated by repression, fascism, and co-optation after World War I, much of its cadre joined the Communist International after grassroots workers’ democracy rose to insurrectionary success in Russia. As Communists, these ex-syndicalists accepted a reformulated role for working-class politics. But from their syndicalist experience they also forged for the International a theory of revolutionary union strategy—prioritizing independent rank and file organization—that was more sophisticated than anything previously developed by Marxists. -

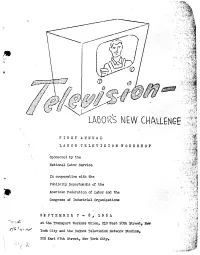

Labor'smew Challenge

LABOR'S MEW CHALLENGE FIRST ANNUAL LABOR TEIEVISIOH WORKSHOP Sponsored by the National Labor Service In cooperation with the Publicity Departments of the American Federation of Labor and the Congress of Industrial Organizations SEPTEMBER 7 - 8, 1 9 5 lj ־at the Transport Workers Union, 210 West 50th Street, New Yoik City and the DuMont Television Network Studios, 205 East 67th Street, New York City# INDEX m TOPICS PAGE Welcoming Address - Harry Fleischman * Labor and Politics on TV - Morris Novik. ........ 1 TV Interview Shows - Jesse Zousmer 7 Labor And Educational TV - Frederick Bate . 9 How To Get Free Time - Lynne Rhodes ........... 11 Free Time for Visiting Labor Leaders - Nat Rudich .... 14 YJhen And How To Use Advertising Agencies - Henry C. Fleisher 16 How To Get The Most For Your TV Money - Paul Miner ... 19 Telecasting For Labor - Guy Nunn. ...... 25 How To Handle Controversy On TV - Tex McCrary ...... 34 TV Film Spots - Harry Fleischman 45 TV CLINIC AT DUMONT STUDIOS 1A Production Problems - Jack Anderson . 2A TV Production Costs - A. L. Hollander 6A K How TV Stations Operate - Norman-Knight 9A m, Gordon Cole 12A ־ w WORKSHOP SUMMARY FIRST ANNUAL LABOR TV WORKSHOP September 7,8, 19Sh WELCOMING ADDRESS: Harry Fleischman, Director, National Labor Service Yfelccme to the first Labor Television Workshop 1 The idea for this get-together began taking shape when it became apparent that TV was the "coming" field of communications. Today, with nearly 33 million sets in American homes, it has certainly arrived. Some of you have asked why the National Labor Service is sponsoring this Workshop. -

1974 Newsletter

Congress of Industrial Organizations CIO Collections "AN INCALCULABLE FORCE was unleashed by the C.I.O." So wrote labor reporter Mary Heaton Vorse in Labor's New Millions. The force and effectiveness of the CIO in bringing vital industrial unionism and political and social consciousness to the American labor movement becomes more discernible and calculable each year. Union records and personal papers of the men and women who supported and led the CIO are being increasingly made available to students and historians. The principal focus of this Newsletter will be on CIO-related collections available to researchers in the Archives. THE CIO SECRETARY-TREASURER COLLECTION The Archives of Labor History and Urban Affairs obtained the files of the CIO Secretary-Treasurer's office in 1966. The collection consists of 120 linear feet of material covering the period 1935-1960 and has been divided into two major sections: the files of James B. Carey, Secretary-Treasurer, 1938-56, and George L. P. Weaver, Assistant Secretary-Treasurer, 1945-50 and 1953-55. James B. Carey succeeded Charles B. Howard as Secretary- Treasurer of the CIO in 1938 and served in that office until 1956, the year after the merger of the American Federation of Labor ( AFL) and Congress of Industrial Organizations ( CIO). In April 197 4, Cesar Chavez, President of the United Farm Mr. Carey served as chairman of the CIO Civil Rights Com- Workers of America, AFL-CIO, visited the Archives during his mittee, CIO delegate to the Second Labor Conference of the speaking engagement in Detroit. Examining one of the several American States in 1939, secretary of the CIO delegation at the hundred United Farm Worker photographs in the Archives with founding of the World Federation of Trade Unions, a partici- Cesar Chavez are left to right, Reverend Monsignor George G. -

TWU 100 Bulletin Sprg2012.Indd

As I Was Saying JOHN SAMUELSEN, PRESIDENT Tier VI, Contract, Milestone THE PAST FEW WEEKS I’VE BEEN FEELING A BIT LIKE 40 IS THE NEW 50. SURGERY DUE TO A JOB RELATED HIP INJURY sidelined me for a couple of weeks, at least physically. But thanks to texting, email and cell phones, I was only out of touch for a day or so. Despite my situation, the work of the union continued thanks to my strong leadership team and a knowledgeable, professional staff. The experience, however, underscored a couple of similar cries of poverty, would declare that finding the things for me – transit workers incur a lot of IOD’s and ad- money “is not my problem. That’s management’s prob- equate health care coverage is essential to our jobs and lives. lem.” We must never waver in our quest for a safer job, and we We’ve gone one better than Quill. We have found the must never flag in our determination to protect our health money for them. They have a lot of it socked away in an benefits for ourselves and our families. obscure fund which currently is flush with nearly $500 million. The City of New York maintains a similar fund, Tier VI Pension and is already drawing down on it for current budgetary Governor Coumo was successful in his quest to imple- needs. ment a Tier VI pension, but TWU Local 100 worked hard to We are also in the process of identifying areas of gross minimize the hit that new transit workers will take. -

At Our 1961 Convention, International President Quill Introduces Dr

In 1965, the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. saluted the TWU and our History. When your union was born in strife during the turbulent times, it grew and developed in the pioneering demo- cratic tradition of a CIO union, with respect to racial equality. Your crusading spirit – which broke through the open shop stronghold also broke through the double walled citadels of race prejudice. – Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. At our 1961 Convention, International President Quill Introduces Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. We are very happy that Dr. King was able to attend this convention of the Transport Workers Union because I think we are reaching the turning point in America. I don’t think any leader since Abraham Lincoln has done as much to unite the American people, black and white, as Dr. King has done in the last 15 years. It is heartening to hear that the barrier against Negroes attending integrated schools is going down in the state of Tennessee. It is heartening to know that an attempt is being made to wipe out segregation in the city of New Rochelle—only 20 miles from the United Nations, here in New York—and it is being done in our time. I don’t think any leader since Abraham Lincoln has done as much to unite the American people, black and white, as Dr. King has done in the last 15 years. Dr. King has tried a new approach to uniting the people of America. He does not advocate a separate Negro Republic. He does not favor arming the Negroes of the South against the white people. -

Dissertation Final Draft

UNITVERISTY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara The Price of Prosperity: Inflation and the Limits of the New Deal Order A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History by Samir Sonti Committee in charge: Professor Nelson Lichtenstein, Chair Professor Mary O. Furner Professor Alice O’Connor Professor Salim Yaqub Professor Kate McDonald March 2017 The dissertation of Samir Sonti is approved. __________________________________________ Kate McDonald __________________________________________ Salim Yaqub __________________________________________ Alice O’Connor __________________________________________ Mary Furner __________________________________________ Nelson Lichtenstein, Committee Chair September 2016 The Price of Prosperity: Inflation and the Limits of the New Deal Order Copyright © 2017 by Samir Sonti iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Dedicated to Jayashree Sonti and Nagesh Sonti Writing a dissertation is at once a solitary and a collective process. Although only my name appears on the title page, and in spite of the countless hours I spent alone while producing draft after draft, I could not have accomplished this on my own. For one, this project would not have been possible without the generous support I received from a number of institutions: The Washington Center for Equitable Growth; the Dirksen Center; the UC Group in Economic History Research; UCSB History Associates; and the UCSB Center for the Study of Work, Labor, and Democracy all provided grants and fellowships that enabled me to travel to archives and complete the research on which this project is based. And the staff at those archives – too many to name all – deserve special recognition. Historians depend upon archives, and archives depend upon archivists. They are the unsung heroes without whom there would be no hope of recovering the past. -

The Transport Workers Union and Labor Anti-Communism in Miami During the 1940S

Labor Histoy, Vol. 39, No. I, 1998 7 Putting Labor’s House in Order: the Transport Workers Union and labor anti-Communism in Miami during the 1940s ALEX LICHTENSTEIN “Miami Chosen Center of Latin Red Network,” screamed the headlines of the Miami Daily News on May 9 1949. Over the next 10 days, the paper ran a series written by former Communist Party (CP) and Transport Workers Union (TWU)member, Paul Crouch, exposing Communist infiltration of the Manhattan Project, Soviet plans to use the domestic CP apparatus to help overthrow the US government and capture the Panama Canal, and the Party’s plans to foment a “negro revolt” in the South. For his Miami audience, Crouch emphasized that the city’s powerful Transport Workers Union, with over 2000 Pan American Airlines workers in its ranks the largest CIO affiliate in Florida, was controlled by the Communists. Even though the TWU’s international president, Michael Quill, had broken with the Party the year before, he had so far been unable to purge Communists from the ranks of Miami’s Local 500, the union’s largest air transport unit. As a consequence, Crouch proclaimed, “the Commu- nist Party could ground every plane operated by Pan American in the western hemi- sphere.” And in his most explosive charge, Crouch claimed that a Latin American red courier network operated under cover of the union.’ After Whittaker Chambers and Elizabeth Bentley, Crouch was probably the most important ex-Communist red exposer the Cold War produced. Of course, there is good reason to doubt his reliability; indeed, even the FBI dismissed his allegation that Pan Am flight stewards served as CP couriers. -

Public Workers William A

Hunter College From the SelectedWorks of William A. Herbert 2019 Public Workers William A. Herbert This work is licensed under a Creative Commons CC_BY-NC International License. Available at: https://works.bepress.com/william_herbert/45/ CHAPTER 11 by William A. Herbert Public Workers ublic workers began self-organ- izing in New York City in the late 19th and early 20th cen- Pturies, coinciding with an increase in governmental services and the ad- vent of civil service reform. Various associations of federal, state, immunity from hard work. The ste- and local government workers reotype is more than a century old. formed along occupational (post- It was used in a May 1911 speech by al, sanitation, and clerical workers; President William Howard Taft to teachers, police, and firefighters) justify placing conditions on public and departmental lines, or accord- workers “that should not be and ing to civil service status. An early, ought not be imposed upon those important goal of many employee who serve private employers.” associations was enforcement of It remains a rhetorical tool used to civil service rules, a goal shared by create divisions between public- government-reform groups to end and private-sector workers, and political patronage-based deci- to attack collective bargaining, job sion-making. security protections, and pensions. Organizational strength varied. Some early New York public Interunion rivalries and factional dis- employee organizations affiliated putes, as well as political and strate- with the labor movement, which had gic differences, permeate much long sought to make government a of the city’s public-sector labor his- “model employer” as a means of per- tory. -

Police Fraternity and the Politics of Race and Class in New York City, 1941-1960 by Andrew Darien

LABOR HISTORY Regional Labor Review Spring 2000 Police Fraternity and the Politics of Race and Class in New York City, 1941-1960 by Andrew Darien The Police Department of the City of New York is an organization composed of real Americans. So far as the individual member is concerned, whether he be Catholic, Protestant or Jew, Republican or Democrat, Negro or white, matters not at all. We are working together in harmony . --NY City Police Commissioner Lewis J. Valentine, 1945 1 Police executives in the second half of the twentieth century have embraced police fraternity and an ideology of neutrality, objectivity, and "color-blindness” as a response to the pressure brought to bear upon them by the modern civil rights movement and the Policemen’s Benevolent Association (PBA). Commissioner Valentine’s appeal to patriotism reflected his anxiety over, and effort to, combat the troubling divisions among his ranks, rather than an accurate portrayal of police solidarity. As the United States consummated a war against Nazi racism and planned for a showdown with Soviet communism, black civil rights activists would compel the nation to come to terms with racial segregation and the oppressive practices of municipal police departments. At the same time, the mostly white rank-and-file officers in the PBA would challenge police management’s prerogative to dictate their pay and hours as well as their political and social affiliations. Nevertheless, as would be the case well into the late twentieth century, the PBA would fail to make the connection between the struggles of black citizens and officers of color and its own victimization at the hands of management.