The Way of Light Durham to Heavenfield

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Subject Guide 1 – Records Relating to Inclosure

Durham County Record Office County Hall Durham DH1 5UL Telephone: 03000 267619 Email: [email protected] Website: www.durhamrecordoffice.org.uk Subject Guide 1 – Records Relating to Inclosure Issue no. 19 July 2020 Contents Introduction 1 Organisation of List 2 Alphabetical List of Townships 2 A 2 B 2 C 3 D 4 E 4 F 4 G 4 H 5 I 5 K 5 L 5 M 6 N 6 O 6 R 6 S 7 T 7 U 8 W 8 Introduction Inclosure (occasionally spelled “enclosure”) refers to a reorganisation of scattered land holdings by mutual agreement of the owners. Much inclosure of Common Land, Open Fields and Moor Land (or Waste), formerly farmed collectively by the residents on behalf of the Lord of the Manor, had taken place by the 18th century, but the uplands of County Durham remained largely unenclosed. Inclosures, to consolidate land-holdings, divide the land (into Allotments) and fence it off from other usage, could be made under a Private Act of Parliament or by general agreement of the landowners concerned. In the latter case the Agreement would be Enrolled as a Decree at the Court of Chancery in Durham and/or lodged with the Clerk of the Peace, the senior government officer in the County, so may be preserved in Quarter Sessions records. In the case of Parliamentary Enclosure a Local Bill would be put before Parliament which would pass it into law as an Inclosure Act. The Acts appointed Commissioners to survey the area concerned and determine its distribution as a published Inclosure Award. -

Christina Rossetti

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com ChristinaRossetti MackenzieBell,HellenaTeresaMurray,JohnParkerAnderson,AgnesMilne the g1ft of Fred Newton Scott l'hl'lll'l'l'llllftlill MMM1IIIH1I Il'l'l lulling TVr-K^vr^ lit 34-3 y s ( CHRISTINA ROSSETTI J" by thtie s-ajmis atjthoe. SPRING'S IMMORTALITY: AND OTHER POEMS. Th1rd Ed1t1on, completing 1,500 copies. Cloth gilt, 3J. W. The Athen-cum.— ' Has an unquestionable charm of its own.' The Da1ly News.— 'Throughout a model of finished workmanship.' The Bookman.—' His verse leaves on us the impression that we have been in company with a poet.' CHARLES WHITEHEAD : A FORGOTTEN GENIUS. A MONOGRAPH, WITH EXTRACTS FROM WHITEHEAD'S WORKS. New Ed1t1on. With an Appreciation of Whitehead by Mr, Hall Ca1ne. Cloth, 3*. f»d. The T1mes. — * It is grange how men with a true touch of genius in them can sink out of recognition ; and this occurs very rapidly sometimes, as in the case of Charles Whitehead. Several works by this wr1ter ought not to be allowed to drop out of English literature. Mr. Mackenzie Bell's sketch may consequently be welcomed for reviving the interest in Whitehead.' The Globe.—' His monograph is carefully, neatly, and sympathetically built up.' The Pall Mall Magaz1ne.—' Mr. Mackenzie Bell's fascinating monograph.' — Mr. /. ZangwiU. PICTURES OF TRAVEL: AND OTHER POEMS. Second Thousand. Cloth, gilt top, 3*. 6d. The Queen has been graciously pleased to accept a copy of this work, and has, through her Secretary, Sir Arthur Bigge, conveyed her thanks to the Author. -

Our Economy 2020 with Insights Into How Our Economy Varies Across Geographies OUR ECONOMY 2020 OUR ECONOMY 2020

Our Economy 2020 With insights into how our economy varies across geographies OUR ECONOMY 2020 OUR ECONOMY 2020 2 3 Contents Welcome and overview Welcome from Andrew Hodgson, Chair, North East LEP 04 Overview from Victoria Sutherland, Senior Economist, North East LEP 05 Section 1 Introduction and overall performance of the North East economy 06 Introduction 08 Overall performance of the North East economy 10 Section 2 Update on the Strategic Economic Plan targets 12 Section 3 Strategic Economic Plan programmes of delivery: data and next steps 16 Business growth 18 Innovation 26 Skills, employment, inclusion and progression 32 Transport connectivity 42 Our Economy 2020 Investment and infrastructure 46 Section 4 How our economy varies across geographies 50 Introduction 52 Statistical geographies 52 Where do people in the North East live? 52 Population structure within the North East 54 Characteristics of the North East population 56 Participation in the labour market within the North East 57 Employment within the North East 58 Travel to work patterns within the North East 65 Income within the North East 66 Businesses within the North East 67 International trade by North East-based businesses 68 Economic output within the North East 69 Productivity within the North East 69 OUR ECONOMY 2020 OUR ECONOMY 2020 4 5 Welcome from An overview from Andrew Hodgson, Chair, Victoria Sutherland, Senior Economist, North East Local Enterprise Partnership North East Local Enterprise Partnership I am proud that the North East LEP has a sustained when there is significant debate about levelling I am pleased to be able to share the third annual Our Economy report. -

The North Pennines

LANDSCAPE CHARACTER THE NORTH PENNINES The North Pennines The North Pennines The North Pennines Countryside Character Area County Boundary Key characteristics • An upland landscape of high moorland ridges and plateaux divided by broad pastoral dales. • Alternating strata of Carboniferous limestones, sandstones and shales give the topography a stepped, horizontal grain. • Millstone Grits cap the higher fells and form distinctive flat-topped summits. Hard igneous dolerites of the Great Whin Sill form dramatic outcrops and waterfalls. • Broad ridges of heather moorland and acidic grassland and higher summits and plateaux of blanket bog are grazed by hardy upland sheep. • Pastures and hay meadows in the dales are bounded by dry stone walls, which give way to hedgerows in the lower dale. • Tree cover is sparse in the upper and middle dale. Hedgerow and field trees and tree-lined watercourses are common in the lower dale. • Woodland cover is low. Upland ash and oak-birch woods are found in river gorges and dale side gills, and larger conifer plantations in the moorland fringes. • The settled dales contain small villages and scattered farms. Buildings have a strong vernacular character and are built of local stone with roofs of stone flag or slate. • The landscape is scarred in places by mineral workings with many active and abandoned limestone and whinstone quarries and the relics of widespread lead workings. • An open landscape, broad in scale, with panoramic views from higher ground to distant ridges and summits. • The landscape of the moors is remote, natural and elemental with few man made features and a near wilderness quality in places. -

Contents Hawthorn Dene, 1, 5-Jul-1924

Northern Naturalists’ Union Field Meeting Reports- 1924-2005 Contents Hawthorn Dene, 1, 5-jul-1924 .............................. 10 Billingham Marsh, 2, 13-jun-1925 ......................... 13 Sweethope Lough, 3, 11-jul-1925 ........................ 18 The Sneap, 4, 12-jun-1926 ................................... 24 Great Ayton, 5, 18-jun-1927 ................................. 28 Gibside, 6, 23-jul-1927 ......................................... 28 Langdon Beck, 7, 9-jun-1928 ............................... 29 Hawthorn Dene, 8, 5-jul-1928 .............................. 33 Frosterley, 9 ......................................................... 38 The Sneap, 10, 1-jun-1929 ................................... 38 Allenheads, 11, 6-july-1929 .................................. 43 Dryderdale, 12, 14-jun-1930 ................................. 46 Blanchland, 13, 12-jul-1930 .................................. 49 Devil's Water, 14, 15-jun-1931 ............................. 52 Egglestone, 15, 11-jul-1931 ................................. 53 Windlestone Park, 16, June? ............................... 55 Edmondbyers, 17, 16-jul-1932 ............................. 57 Stanhope and Frosterley, 18, 5-jun-1932 ............. 58 The Sneap, 19, 15-jul-1933 .................................. 61 Pigdon Banks, 20, 1-jun-1934 .............................. 62 Greatham Marsh, 21, 21-jul-1934 ........................ 64 Blanchland, 22, 15-jun-1935 ................................ 66 Dryderdale, 23, ..................................................... 68 Raby Park, -

Coast to Coast

Coast to Coast “You xxxx” I shouted – more than once if remember correctly. My ire was directed at Raz. We were zipping along a disused railway line between Keswick and Penrith when he suddenly screamed to a halt right in front of me leaving me almost no time to avoid him and get my feet out of the pedal stops and avoid a nasty case of gravel rash. He’d seen a pound coin and had to stop to claim it. I’d have given him a pound if I’d known he was that hard up! This was the first of three days on the Coast to Coast (C2C) bike ride. Dan, Raz and I were the riders with Zoe in the vital support role. Ade was supposed to be with us but Sarah’s broken ankle (one of their dogs knocked her over) just days before meant he had to pull out. It simplified the logistics but Ade missed an entertaining trip. Accommodation in the usual starting place (Whitehaven) was limited so we started at St Bees. Our drive there with our three bikes on the back of the Focus was in the dry much to our surprise. Not that Raz and I noticed much of the journey! We kept our fingers crossed for the weather! Quickly dumping our bags in the Fairladies Barn Guest house, we rode off to the beach to dip our wheels ceremonially in the Irish Sea. The pub meal we had was frankly pretty awful and when we emerged, it was raining. In the night there was apparently a major storm with power cuts but all we noticed was that our telly came on in the middle of the night as power was restored. -

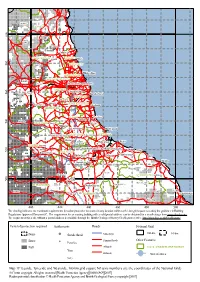

Map 19 Teeside, Tyneside and Wearside, 100-Km Grid Square NZ (Axis Numbers Are the Coordinates of the National Grid) © Crown Copyright

Alwinton ALNWICK 0 0 6 Elsdon Stanton Morpeth CASTLE MORPETH Whalton WANSBECK Blyth 0 8 5 Kirkheaton BLYTH VALLEY Whitley Bay NORTH TYNESIDE NEWCASTLE UPON TYNE Acomb Newton Newcastle upon Tyne 0 GATESHEAD 6 Dye House Gateshead 5 Slaley Sunderland SUNDERLAND Stanley Consett Edmundbyers CHESTER-LE-STREET Seaham DERWENTSIDE DURHAM Peterlee 0 Thornley 4 Westgate 5 WEAR VALLEY Thornley Wingate Willington Spennymoor Trimdon Hartlepool Bishop Auckland SEDGEFIELD Sedgefield HARTLEPOOL Holwick Shildon Billingham Redcar Newton Aycliffe TEESDALE Kinninvie 0 Stockton-on-Tees Middlesbrough 2 Skelton 5 Loftus DARLINGTON Barnard Castle Guisborough Darlington Eston Ellerby Gilmonby Yarm Whitby Hurworth-on-Tees Stokesley Gayles Hornby Westerdale Faceby Langthwaite Richmond SCARBOROUGH Goathland 0 0 5 Catterick Rosedale Abbey Fangdale Beck RICHMONDSHIRE Hornby Northallerton Leyburn Hawes Lockton Scalby Bedale HAMBLETON Scarborough Pickering Thirsk 400 420 440 460 480 500 The shading indicates the maximum requirements for radon protective measures in any location within each 1-km grid square to satisfy the guidance in Building Regulations Approved Document C. The requirement for an existing building with a valid postal address can be obtained for a small charge from www.ukradon.org. The requirement for a site without a postal address is available through the British Geological Survey GeoReports service, http://shop.bgs.ac.uk/GeoReports/. Level of protection required Settlements Roads National Grid None Sunderland Motorways 100-km 10-km Basic Primary Roads Other Features Peterlee Full A Roads LOCAL ADMINISTRATIVE DISTRICT Yarm B Roads Water features Slaley Map 19 Teeside, Tyneside and Wearside, 100-km grid square NZ (axis numbers are the coordinates of the National Grid) © Crown copyright. -

Landscape and Visual Impact Appriasal Proposed Western Relief Road

LANDSCAPE AND VISUAL IMPACT APPRIASAL PROPOSED WESTERN RELIEF ROAD Contents 1 Introduction 1.1 Scope and purpose of the appraisal 1.2 Methodology 2. Landscape and visual baseline 2.1 Landscape character 2.1.1 National Character Areas / County Character Areas 2.1.2 Broad Landscape Types and Character Areas 2.1.3 Local Character Areas 2.1.4 Local Landscape Types and subtypes 2.2 Landscape features 2.2.1 Landform 2.2.2 Woodlands and scrub 2.2.3 Field boundaries and field trees 2.2.4 Wetlands and watercourses 2.2.5 Other features 2.3 Landscape value 2.3.1 National Designations 2.3.2 Local designations 2.3.3 Other designations 2.3.4 Local landscape strategies 2.3.5 Tree Preservation Orders 2.3.6 Values and attributes 3. Visual baseline • Visibility • Visual receptors • Viewpoints and views 4 Potential landscape effects 4.1 Landscape features 4.1.1 Landform 4.1.2 Woodlands and scrub 4.1.3 Field boundaries and field trees 4.1.4 Wetlands and watercourses 4.1.5 Other features 4.2 Landscape character 4.2.1 National Character Areas / County Character Areas 4.2.2 Broad Landscape Types and Character Areas 4.2.3 Local Character Areas 4.3 Designated Landscapes 4.3.1 Area of High Landscape Value 4.3.2 Parks and Gardens of Local Interest 4.3.3 Green Belt 5 Potential visual effects 5.1 Residents 5.2 Walkers, cyclists and horse riders 5.4 Motorists 6. Mitigation 7. Conclusions Appendices Appendix 1: Methodology Appendix 2: Figures Figure 1: National Character Areas and County Character Areas Figure 2: Broad Landscape Types and Character Areas Figure 3: Local -

Directory Derwentside

DERWENTSIDE Business 06 07 & / Community DIRECTORY Background Information con t en t s Premise, by Right Honorable Hilary Armstrong 3 Derwentside the District 5 “If we do what Introduction, by LSP Chair, Alex Watson 7 we’ve always Business & Economy done then we’ll A great place for business 9 only get what Derwentside economic profile 11 we’ve always Business support and partnerships 3 got” Flagship projects (Emerge, Beacon, Agility, Enterprise Place) 15 Tom Baker Your business matters 17 Education Lifelong Learning and education 19 Community Safety Safety in the community 19 E d it or Miles Crofton In the Best of Health 0191 586 6010 [email protected] Healthy living for a healthy lifestyle 19 Exxecu t ivve Eddit oor Housing & Environment Sarah J Lee An environment for success 19 [email protected] Childcare counts 19 Ed it oria l Paul Seales You and your Council 19 [email protected] Transport and communication 19 A dv ertisin g & Sponsorship Time out with tourism, leisure and shopping 19 Andrew White 0191 5866 040 Miscellaneous Case Studies 19 Bank Holidays 19 Derwentside Business & Community Directory is published by informnorth creative services, Calendar 2006 19 a County Durham based community interest company. We have taken all reasonable care to Conversions 19 ensure that material is accurate at the time of going to press, but accept no responsibility for Dialling Codes 19 errors or omissions and no liability is accepted for omission or failure from any cause. Travelling distances to UK centres 19 The publisher has welcomed contributions in production of this directory, all opinions UK& Ireland airports list 19 expressed are those of individual contributors and not necessarily our own. -

County Durham Settlement Study September 2017 Planning the Future of County Durham 1 Context

County Durham Plan Settlement Study June 2018 Contents 1. CONTEXT 2 2. METHODOLOGY 3 3. SCORING MATRIX 4 4. SETTLEMENTS 8 County Durham Settlement Study September 2017 Planning the future of County Durham 1 Context 1 Context County Durham has a population of 224,000 households (Census 2011) and covers an area of 222,600 hectares. The County stretches from the North Pennines Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) in the west to the North Sea Heritage Coast in the east and borders Gateshead and Sunderland, Northumberland, Cumbria and Hartlepool, Stockton, Darlington and North Yorkshire. Although commonly regarded as a predominantly rural area, the County varies in character from remote and sparsely populated areas in the west, to the former coalfield communities in the centre and east, where 90% of the population lives east of the A68 road in around half of the County by area. The Settlement Study 2017 seeks to provide an understanding of the number and range of services available within each of the 230 settlements within County Durham. (a) Identifying the number and range of services and facilities available within a settlement is useful context to inform decision making both for planning applications and policy formulation. The range and number of services within a settlement is usually, but not always, proportionate to the size of its population. The services within a settlement will generally determine a settlement's role and sphere of influence. This baseline position provides one aspect for considering sustainability and should be used alongside other relevant, local circumstances. County Durham a 307 Settlements if you exclude clustering 2 Planning the future of County Durham County Durham Settlement Study September 2017 Methodology 2 2 Methodology This Settlement Study updates the versions published in 2009 and 2012 and an updated methodology has been produced following consultation in 2016. -

Hamsterley Forest 1 Weardalefc Picture Visitor Library Network / John Mcfarlane Welcome to Weardale

Welcome to Weardale Things to do and places to go in Weardale and the surrounding area. Please leave this browser complete for other visitors. Image : Hamsterley Forest www.discoverweardale.com 1 WeardaleFC Picture Visitor Library Network / John McFarlane Welcome to Weardale This bedroom browser has been compiled by the Weardale Visitor Network. We hope that you will enjoy your stay in Weardale and return very soon. The information contained within this browser is intended as a guide only and while every care has been taken to ensure its accuracy readers will understand that details are subject to change. Telephone numbers, for checking details, are provided where appropriate. Acknowledgements: Design: David Heatherington Image: Stanhope Common courtesy of Visit England/Visit County Durham www.discoverweardale.com 2 Weardale Visitor Network To Hexham Derwent Reservoir To Newcastle and Allendale Carlisle A69 B6295 Abbey Consett River Blanchland West Muggleswick A 692 Allen Edmundbyers Hunstanworth A 691 River Castleside East Allen North Pennines Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty Lanchester A 68 B6278 C2C C2C Allenheads B6296 Heritage C2C Centre Hall Hill B6301 Nenthead Farm C2C Rookhope A 689 Lanehead To Alston Tunstall Penrith Cowshill Reservoir M6 Killhope Lead Mining The Durham Dales Centre Museum Wearhead Stanhope Eastgate 3 Ireshopeburn Westgate Tow Law Burnhope B6297 Reservoir Wolsingham B6299 Weardale C2C Frosterley N Museum & St John’s Chapel Farm High House Trail Chapel Weardale Railway Crook A 689 Weardale A 690 Ski Club Weardale -

Popular Political Oratory and Itinerant Lecturing in Yorkshire and the North East in the Age of Chartism, 1837-60 Janette Lisa M

Popular political oratory and itinerant lecturing in Yorkshire and the North East in the age of Chartism, 1837-60 Janette Lisa Martin This thesis is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of York Department of History January 2010 ABSTRACT Itinerant lecturers declaiming upon free trade, Chartism, temperance, or anti- slavery could be heard in market places and halls across the country during the years 1837- 60. The power of the spoken word was such that all major pressure groups employed lecturers and sent them on extensive tours. Print historians tend to overplay the importance of newspapers and tracts in disseminating political ideas and forming public opinion. This thesis demonstrates the importance of older, traditional forms of communication. Inert printed pages were no match for charismatic oratory. Combining personal magnetism, drama and immediacy, the itinerant lecturer was the most effective medium through which to reach those with limited access to books, newspapers or national political culture. Orators crucially united their dispersed audiences in national struggles for reform, fomenting discussion and coalescing political opinion, while railways, the telegraph and expanding press reportage allowed speakers and their arguments to circulate rapidly. Understanding of political oratory and public meetings has been skewed by over- emphasis upon the hustings and high-profile politicians. This has generated two misconceptions: that political meetings were generally rowdy and that a golden age of political oratory was secured only through Gladstone’s legendary stumping tours. However, this thesis argues that, far from being disorderly, public meetings were carefully regulated and controlled offering disenfranchised males a genuine democratic space for political discussion.