Interview Transcript ( .Pdf )

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume 44 Number 4 Oct Nov Dec 2018

THE INDEPENDENT JOURNAL OF CREATIVE IMPROVISED MUSIC ODEAN POPE PHIL MINTON SKETY SCOTT ROBINSON STEVE COHN KEIKO JONES MONTREAL JAZZ FESTIVAL 2018 INTERNATIONAL JAZZ NEWS CD REVIEWS BOOK REVIEWS DVD REVIEWS OBITUARIES Volume 44 Number 4 Oct Nov Dec 2018 New Releases on CNM Records POCKET ACES, CULL THE HEARD (CNM032) - OUT NOW. - Pocket Aces emerged from the jazz trio tradition; where each voice balances the others through contrast, and surprise. Although freely improvised, the music of Pocket Aces is consciously compositional, given to bouts of form, groove, and crafty melodies. Distillation of ideas with a premium on space and tone provides a strong coherence as the trio navigates the familiar and unfamiliar. HOFBAUER/ROSENTHANL QUARTET, HUMAN RESOURCES (CNM033) - RELEASE DATE NOV. 9 THE HOFBAUER/ROSENTHAL QUARTET, unites four imaginative improvisors from Boston’s eclectic jazz scene. There’s a non-hierarchal notion of the ensemble in this project, an ideal of equality and a selfless determination built into every musical inclination, as they unabashedly swing at the intersection between the clarity and control of bop and the brash freedom of the avant-garde. ERIC HOFBAUER QUARTET, PREHISTORIC JAZZ VOL. 4: REMINISCING IN TEMPO - OUT NOW. Reimagining of the rarely heard 1935 long form Duke Ellington composition. "It's a musical jungle gym for the guitar fan, a close listening to Hofbauer's note choices and abstract connections to the song's structure is absolutely required listening." - Paul Acquaro, Free Jazz Blog. All Albums on Bandcamp.com, Amazon.com or Erichofbauer.com - Visit erichofbauer.com for album details, audio samples, press and more. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE in the Land of Perfect

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE In the Land of Perfect Bliss A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing and Writing for the Performing Arts by Simona Suresh Supekar August 2013 Thesis Committee: Professor Andrew Winer, Co-Chairperson Professor Tod Goldberg, Co-Chairperson Professor Mark Haskell Smith Copyright by Simona Suresh Supekar 2013 The Thesis of Simona Suresh Supekar is approved: Committee Co-Chairperson Committee Co-Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements I am indebted to the guidance of Mark Haskell Smith, whose relentless support and spot- on feedback throughout the writing process was crucial to getting this far. I also want to thank Tod Goldberg for accepting me into the program and for his very insightful comments on my work. The smart, thoughtful feedback from Mary Yukari Waters was also instrumental in getting my story where it needed to be. Thanks also to my many colleagues at UCR who provided very valuable comments on my work and whose work I too admire. I am so lucky to have had you as friends in this program, so much so that I copied verbatim the first half of this sentence from the sample acknowledgments page in the thesis review packet. Last, I want to thank my parents Suresh and Shaila Supekar who gave me the stories to tell and the desire to tell them by virtue of just being here, in America, as immigrants who left so much behind in India. And of course, none of my work would be possible without the love—upon which everything is built, really—from my partner Arturo Aguilar, who pushed me to follow my dream and has supported me in every way throughout this journey. -

By Aaron Jay Kernis

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2016 “A Voice, A Messenger” by Aaron Jay Kernis: A Performer's Guide and Historical Analysis Pagean Marie DiSalvio Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation DiSalvio, Pagean Marie, "“A Voice, A Messenger” by Aaron Jay Kernis: A Performer's Guide and Historical Analysis" (2016). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3434. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3434 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. “A VOICE, A MESSENGER” BY AARON JAY KERNIS: A PERFORMER’S GUIDE AND HISTORICAL ANALYSIS A Written Document Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Pagean Marie DiSalvio B.M., Rowan University, 2011 M.M., Illinois State University, 2013 May 2016 For my husband, Nicholas DiSalvio ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my committee, Dr. Joseph Skillen, Prof. Kristin Sosnowsky, and Dr. Brij Mohan, for their patience and guidance in completing this document. I would especially like to thank Dr. Brian Shaw for keeping me focused in the “present time” for the past three years. Thank you to those who gave me their time and allowed me to interview them for this project: Dr. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS I. The Issue of Extremism in the Czech Republic in 2010 1 1. Introduction 1 1.1 Definition of Terms 2 2. Extremism in the Czech Republic in 5"#$% 10 3 2.1 Brief Characteristics of the Extremist Scene 3 2.1.1 Right-wing Extremism 3 2.1.1.1 The Neo-Nazi Scene 3 2.1.1.2 Ultra Right-Wing Groups 14 2.1.1.3 2010: Trends at the Right-Wing Extremist Scene 15 2.1.1.4 Application of State Power with Regard to the Right of Assembly in Relation to Right-Wing Extremist Entities 15 2.1.2 Left-Wing Extremism 17 2.1.2.1 Anarcho-autonomous Movement 17 2.1.2.2 Marxist-Leninist Groups 18 2.1.2.3 2010: Trends at the Left-Wing Extremist Scene 19 2.2. The Issue of Right-Wing Extremist bands and Right-Wing Extremist Demonstrations; Right-Wing Extremist Web Pages Accessible on the Internet 20 2.2.1 White Power Music Concerts 20 2.2.2 Demonstrations and Assemblies of Right-Wing Extremists 21 2.2.3 Other Events Held by Right-Wing Extremists 23 2.3 Activities of Left-Wing Extremists 23 2.3.1 Assemblies and Public Actions 23 2.3.2 Ticket Nights and Concerts 24 2.3.3 Other Events 24 2.4 The Issue of the Internet 24 2.4.1 Internet and Virtual Environment 24 2.4.2 Right-Wing Extremist Web Pages 25 2.5 Crimes Having an Extremist Context in 2010 33 2.5.1 The Situation in the Czech Republic and in Individual Regions 34 2.5.1.1 Overall Situation 34 2.5.1.2 Composition of Criminal Offences 36 2.5.1.3 Offenders 38 2.5.1.4 Crimes with an Extremist Context Committed by Police Officers 40 2.5.1.5 Crimes with an Extremist Context Committed by Members of the -

Living Without Regret

FORERUNNER SCHOOL OF MINISTRY – MIKE BICKLE STUDIES IN THE MILLENNIAL KINGDOM Transcript: 1/28/06 Living Without Regret Tonight, we are going to talk about the saints ruling in the millennial kingdom: one of the most practical subjects in the Word of God. Believe it or not, the subject of the millennial kingdom, Jesus’ earthly reign for a thousand years is one of the most prominent themes in Scriptures. Yet it is often neglected, and most believers are pretty vague about it. THE MILLENNIAL KINGDOM IS ONE OF THE MAJOR REVELATIONS There is so much detail about it particularly in the Old Testament. It is not just prominent; it is practical. Our lives do not make sense even as believers except that we understand the relationship of our struggle in this age to what we are going to do in the age to come. Without that piece of information in our understanding, we are significantly lacking in terms of perspective. We are constantly trying to rise up, press in, and hang in there; but we do not quite know why. We know it is for God in a big sort of way, but we cannot relate the struggle, and sacrifices of our lives in this age to the age to come in a practical earthly way. Our life is going to have a practical, earthly expression in the age to come. We will talk about that more in a moment. Roman numeral I. Introduction to the millennial kingdom. John the apostle said in Revelation 20:4-6: “I saw thrones, and they sat on them, and judgment was given unto them: and I saw the souls of them that were beheaded for the witness of Jesus, and for the word of God, and which had not worshiped the beast, neither his image, neither had received his mark upon their foreheads, or in their hands; and they lived and reigned with Christ a thousand years. -

Acdsee Proprint

BULK RATE U.S. POSTAGE PAID Permit No. 2419 lPE lPITClHl K.C., Mo. FREE FREE VOL. II NO. 1 YOU'LL NEVER GET RICH READING THE PITCH FEBRUARY 1981 FBIIRUARY II The 8-52'5 Meet BUDGBT The Rev. in N.Y. Third World Bit List .ONTHI l ·TRIVIA QUIZ· WHAT? SQt·1E RECORD PRICES ARE ACTUALLY ~~nll .815 m wi. i .••lIIi .... lllallle,~<M0,~ CGt4J~G ·DOWN·?····· S€f ·PAGE: 3. FOR DH AI LS , prizes PAGE 2 THE PENNY PITCH LETTERS Dec. 29,1980 Dear Warren, Over the years, Kansas Attorney General's have done many strange things. Now the Kansas Attorney General wants to stamp out "Mumbo Jumbo." 4128 BROADWAY KANSAS CITY, MISSOURI 64111 Does this mean the "Immoral Minority" (816) 561·1580 will be banned from Kansas? Is being banned from Kansas a hardship? Edi tor ....••..•••.• vifarren Stylus Morris Martin Contributing vlriters this issue: Raytown, Mo. P.S. He probably doesn't like dreadlocks Rev. Dwight Frizzell, Lane & Dave from either. GENCO labs, Blind Teddy Dibble, I-Sheryl, Ie-Roths, Lonesum Chuck, Mr.D-Conn, Le Roi, Rage n i-Rick, P. Minkin, Lindsay Shannon, Mr. P. Keenan, G. Trimble, Jan. 26, 1981 debranderson, M. Olson Dear Editor, Inspiration this issue: How come K. C. radio stations never Fred de Cordova play, The Inmates "I thought I heard a Heartbeat", Roy Buchanan "Dr. Rock & Roll" Peter Green, "Loser Two Times", Marianne r,------:=~--~-__l "I don' t care what they say about Faithfull, "Broken English", etc, etc,? being avant garde or anything else. How come? Frankly, call me square if you want Is this a plot against the "Immoral to. -

Events That Led to the Czechoslovakian Prague Spring and Its Immediate Aftermath

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Senior Theses and Projects Student Scholarship Spring 2015 Events that led to the Czechoslovakian Prague Spring and its immediate aftermath Natalie Babjukova Trinity College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses Recommended Citation Babjukova, Natalie, "Events that led to the Czechoslovakian Prague Spring and its immediate aftermath". Senior Theses, Trinity College, Hartford, CT 2015. Trinity College Digital Repository, https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses/469 Events that led to the Czechoslovakian Prague Spring and its immediate aftermath Senior thesis towards Russian major Natalie Babjukova Spring 2015 ` The invasion of Czechoslovakia by the Soviet Union on August 21 st 1968 dramatically changed not only Czech domestic, as well as international politics, but also the lives of every single person in the country. It was an intrusion of the Soviet Union into Czechoslovakia that no one had expected. There were many events that led to the aggressive action of the Soviets that could be dated way back, events that preceded the Prague Spring. Even though it is a very recent topic, the Cold War made it hard for people outside the Soviet Union to understand what the regime was about and what exactly was wrong about it. Things that leaked out of the country were mostly positive and that is why the rest of the world did not feel the need to interfere. Even within the country, many incidents were explained using excuses and lies just so citizens would not want to revolt. Throughout the years of the communist regime people started realizing the lies they were being told, but even then they could not oppose it. -

Recorded Jazz in the 20Th Century

Recorded Jazz in the 20th Century: A (Haphazard and Woefully Incomplete) Consumer Guide by Tom Hull Copyright © 2016 Tom Hull - 2 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................................1 Individuals..................................................................................................................................................2 Groups....................................................................................................................................................121 Introduction - 1 Introduction write something here Work and Release Notes write some more here Acknowledgments Some of this is already written above: Robert Christgau, Chuck Eddy, Rob Harvilla, Michael Tatum. Add a blanket thanks to all of the many publicists and musicians who sent me CDs. End with Laura Tillem, of course. Individuals - 2 Individuals Ahmed Abdul-Malik Ahmed Abdul-Malik: Jazz Sahara (1958, OJC) Originally Sam Gill, an American but with roots in Sudan, he played bass with Monk but mostly plays oud on this date. Middle-eastern rhythm and tone, topped with the irrepressible Johnny Griffin on tenor sax. An interesting piece of hybrid music. [+] John Abercrombie John Abercrombie: Animato (1989, ECM -90) Mild mannered guitar record, with Vince Mendoza writing most of the pieces and playing synthesizer, while Jon Christensen adds some percussion. [+] John Abercrombie/Jarek Smietana: Speak Easy (1999, PAO) Smietana -

June 2010 Issue

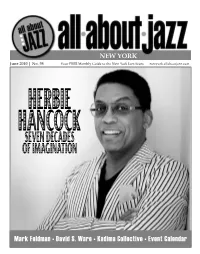

NEW YORK June 2010 | No. 98 Your FREE Monthly Guide to the New York Jazz Scene newyork.allaboutjazz.com HERBIE HANCOCKSEVEN DECADES OF IMAGINATION Mark Feldman • David S. Ware • Kadima Collective • Event Calendar NEW YORK Despite the burgeoning reputations of other cities, New York still remains the jazz capital of the world, if only for sheer volume. A night in NYC is a month, if not more, anywhere else - an astonishing amount of music packed in its 305 square miles (Manhattan only 34 of those!). This is normal for the city but this month, there’s even more, seams bursting with amazing concerts. New York@Night Summer is traditionally festival season but never in recent memory have 4 there been so many happening all at once. We welcome back impresario George Interview: Mark Feldman Wein (Megaphone) and his annual celebration after a year’s absence, now (and by Sean Fitzell hopefully for a long time to come) sponsored by CareFusion and featuring the 6 70th Birthday Celebration of Herbie Hancock (On The Cover). Then there’s the Artist Feature: David S. Ware always-compelling Vision Festival, its 15th edition expanded this year to 11 days 7 by Martin Longley at 7 venues, including the groups of saxophonist David S. Ware (Artist Profile), drummer Muhammad Ali (Encore) and roster members of Kadima Collective On The Cover: Herbie Hancock (Label Spotlight). And based on the success of the WinterJazz Fest, a warmer 9 by Andrey Henkin edition, eerily titled the Undead Jazz Festival, invades the West Village for two days with dozens of bands June. -

Reflections on Rock Music Culture in East Europe and the Soviet Union

Etnomüzikoloji Dergisi Ethnomusicology Journal Yıl/Year: 1 • Sayı/Issue: 2 (2018) Leninism Versus Lennonism; Reflections on Rock Music Culture in East Europe and the Soviet Union Timothy W. Ryback From December 16 to 18, 1965, the Central Committee of the East Ger- man communist party devoted a special session to the ideological welfare of the country’s youth. The committee intended to set the ideological agenda, and to underscore the importance of protecting young people from the per- nicious influences of western youth culture, in particular, the increasingly pervasive phenonemon of rock and pop music. The East German leaders identified gowing rowdiness in schools, drunkenness on the streets, rising in- cidents of criminal activity, including physical asaults and rape, and equally disturbing a noticeble rise in ideological disaffection among the youth. Horst Sindermann, responsible for press and radio, emphasized this latter point with a concrete example. “A 15-year-old, who had not learned a single word of English and who had to leave school in the fifth grade because he could not even speak German properly, sang popular songs in English evening after evening”, Sindermann reported. “How could he do this? He listened to tapes forty times and learned by his own phonetic method to give off sounds that he perceived as being English. There is no doubt that with these methods, you could teach beat music to a parakeet”. The party chairman,Walter Ulbricht, underscored the ideological threat by invoking the lyrics of a song from the Beatles: “The endless monotony of this ‘yeah, yeah, yeah’ is not just ridiculous, it is spirit- ually deadening”. -

Billy Drummond U

Ravi Coltrane I EXCLUSIVE Marian McPartland Book Excerpt DOWNBEAT JACK DEJOHNETTE JACK // RAVI RAVI C OLT R ANE // Jack MA R IAN MCPA IAN DeJohnette’s R TLAN D BIG SOUND // JOEL JOEL Joel Harrison H A rr Endless Guitar ISON // BILLY D BILLY Drum School » Billy Drummond R U mm BLINDFOLD TEST ON D » Bill Stewart TRANSCRIPTION » Tommy Igoe MASTER CLASS » Dan Weiss PRO SESSION NOVEMBER 2012 U.K. £3.50 NOVE M B E R 2012 DOWNBEAT.COM NOVEMBER 2012 VOLUME 79 – NuMBER 11 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Managing Editor Bobby Reed News Editor Hilary Brown Reviews Editor Aaron Cohen Contributing Editors Ed Enright Zach Phillips Art Director Ara Tirado Production Associate Andy Williams Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Michael Point, Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Or- leans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. -

The Demise of Democracy in Czechoslovakia by Boiids

- . ' . THE DEMISE OF DEMOCRACY IN CZECHOSLOVAKIA BY BOIIDS PETRZELKA " Doctor of Law Charles University Prague, Czechoslovakia 1932 Submitted to the faculty of the Graduate School of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS July, 1958 OKLAHOMA STATE UNIVERSITY UBRARY NOV 18 l959 THE DEMISE OF DEMOCRACY IN CZECHOSLOVAKIA Thes i s Approved: r:},,, Thesis Advi ser ~~6/t. Qy~ oWd!-1 Dean of the Graduate School 430804 ii PREFACE During the twenty year period between the Versailles settlement and the collapse of the European security system Czechos lovakia alone among the new states of Europe developed a viable democratic order. Yet with in less than three years after the conclusion of the second World War this "model democracy" wa s overthrown in a coup d'etat by the Communist party with the support of the parliamentary majority and the organized working class. Czechos lovakia is the only democratic republic that has been subverted successfully by Communist s , and the only country that the Communi st s have captured without either recourse to civil warfare--as in Russia, China, Yugoslavia and Vietnam--or to the intervention of the Soviet armed forces--as in the numerous satellite states of Europe and Asia which came under Russian occupation in the wake of the war against the Axis . This thesis i s an attempt to analyse the events which led to the demise of democracy in Czechoslovakia in February, 1948, and to discern the causes for the weakening of the democratic ideology, the spread of Communist influence, and the failure of the legal and political safe guards to preserve the constitutional order of the state.