Bintie: the Wootz Steel in Ancient China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Iron-Making Process

Hopewell Furnace National Historic Site www.nps.gov/hofu Teacher’s Guide The Iron-Making Process The Ingredients The four main ingredients for making iron were present in the area of Hopewell and were a reason for the furnace’s location. I. Wood A. Used as a primary energy source in village operations 1. As charcoal to power the furnace and blacksmith shop 2. As fuel for heating and cooking B. Used as building material for: 1. Homes 2. Wagons and equipment II. Water A. Used to turn the water wheel connected to the bellows which forced blasts of air into the furnace to increase the heat B. Used for: 1. Drinking 2. Bathing 3. Cooking 4. Washing 5. Cleaning III. Iron Ore Iron ore was dug from open-pit mines near Hopewell, then hauled to Hopewell Furnace in carts and wagons IV. Limestone Used as a “flux,” which removed impurities from the ore as the iron ore was smelted; it was quarried near Morgantown and from Hopewell Plantation lands The Process This process was also called smelting. I. In the furnace, the charcoal burns with a great amount of heat. II. The water wheel was attached to a huge bellows and later to blowing tubs — like can be seen at Hopewell today — which blasted the charcoal with air to increase the heat. III. The furnace was filled, or “charged,” from the top in this order: A. Fire B. Charcoal Iron-Making Process Page 1 C. Iron Ore D. Limestone E. Charcoal F. Iron Ore G. The process continued and repeated as the ore melted IV. -

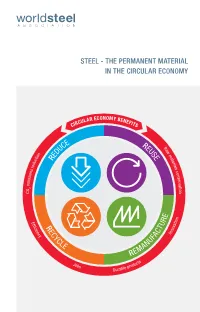

Reduce Reuse Recycle Remanufacture

STEEL - THE PERMANENT MATERIAL IN THE CIRCULAR ECONOMY AR ECONOMY BEN CUL EFI CIR TS E R R C E a U U w n D S m io E E a t t c R e u r i d a e l r s s c n o o n i s s s e i r v m a e t i 2 o O n C E n o E R i f t f U a ic R v o ie T n E n c C In y C Y FA C U LE N MA RE ts Jo duc bs pro Durable 1 CONTENTS Steel in the circular economy 3 Steel is essential to our modern world 5 Reduce 7 Decreasing the amount of material, energy and other resources used to create steel and reducing the weight of steel used in products. Use and reuse 11 Reuse is using an object or material again, either for its original purpose or for a similar purpose, without significantly altering the physical form of the object or material. Remanufacture 15 The process of restoring durable used steel products to as-new condition. Recycle 19 Melting steel products at the end of their useful life to create new steels. Recycling alters the physical form of the steel object so that a new application can be created from the recycled material. End notes 22 2 STEEL IN THE CIRCULAR ECONOMY A sustainable circular economy is one in which steel is fundamental to the circular economy. society reduces the burden on nature by ensuring The industry is continuing to expand its offer resources remain in use for as long as possible. -

Pattern Formation in Wootz Damascus Steel Swords and Blades

Indian Journal ofHistory ofScience, 42.4 (2007) 559-574 PATTERN FORMATION IN WOOTZ DAMASCUS STEEL SWORDS AND BLADES JOHN V ERHOEVEN* (Received 14 February 2007) Museum quality wootz Damascus Steel blades are famous for their beautiful surface patterns that are produced in the blades during the forging process of the wootz ingot. At an International meeting on wootz Damascus steel held in New York' in 1985 it was agreed by the experts attending that the art of making these blades had been lost sometime in nineteenth century or before. Shortly after this time the author began a collaborative study with bladesmith Alfred Pendray to tty to discover how to make ingots that could be forged into blades that would match both the surface patterns and the internal carbide banded microstructure of wootz Damascus steels. After carrying out extensive experiments over a period ofaround 10 years this work succeeded to the point where Pendray is now able to consistently make replicas of museum quality wootz Damascus blades that match both surface and internal structures. It was not until near the end of the study that the key factor in the formation of the surface pattern was discovered. It turned out to be the inclusion of vanadium impurities in the steel at amazingly low levels, as low as 0.004% by weight. This paper reviews the development of the collaborative research effort along with our analysis ofhow the low level of vanadium produces the surface patterns. Key words: Damascus steel, Steel, Wootz Damascus steel. INTRODUCTION Indian wootz steel was generally produced by melting a charge of bloomery iron along with various reducing materials in small closed crucibles. -

Using the Past to Serve the Present’: Comparative Perspectives on Chinese and Western Theories of the Origins of the State*

‘Using the Past to Serve the Present’: Comparative Perspectives on Chinese and * Western Theories of the Origins of the State Yuri Pines and Gideon Shelach One of the interesting peculiarities of the formative age of Chinese intellectual tradition, the Zhanguo period (戰國, ‘Warring States,’ 453–221 BCE), is its thinkers’ preoccupation with the origin of the state. Several recent studies by Chinese and Western scholars have analyzed Zhanguo theories of the formation of political and social institutions, either in the context of the evolution of contemporaneous political and philosophical discourse or as part of ancient Chinese mythology.1 Our discussion proposes a different perspective. By comparing Zhanguo theories of the origin of the state with parallel views developed in Europe and North America in the age of Enlightenment and beyond, we hope to disclose common factors that influenced theoretical thinking in both cases, and thereby to contribute to a general discussion about the evolution of human political thought. We believe that an analysis of ancient Chinese discourse may offer insights into the ways in which the social and political agendas of thinkers shape their theoretical approaches – in ancient China no less than elsewhere. Critics may argue that juxtaposing thinkers from such different cultural and chronological backgrounds is like comparing apples and oranges. Yet this is what cross-cultural comparison always does: It * We are grateful to Prof. Vera Schwarcz and Israel Sorek for their comments on earlier versions of this article, and to Dr Neve Gordon for his useful suggestions. 1 See, e.g., Liu Zehua 劉澤華, Zhongguo chuantong zhengzhi siwei 中國傳統政治思維, Liaoning 1991, pp. -

Higher-Quality Electric-Arc Furnace Steel

ACADEMIC PULSE Higher-Quality Electric-Arc Furnace Steel teelmakers have traditionally viewed Research Continues to Improve the electric arc furnaces (EAFs) as unsuitable Quality of Steel for producing steel with the highest- Even with continued improvements to the Squality surface finish because the process design of steelmaking processes, the steelmaking uses recycled steel instead of fresh iron. With over research community has focused their attention 100 years of processing improvements, however, on the fundamental materials used in steelmaking EAFs have become an efficient and reliable in order to improve the quality of steel. In my lab steelmaking alternative to integrated steelmaking. In at Carnegie Mellon University, we have several fact, steel produced in a modern-day EAF is often research projects that deal with controlling the DR. P. BILLCHRIS MAYER PISTORIUS indistinguishable from what is produced with the impurity concentration and chemical quality of POSCOManaging Professor Editorof Materials integrated blast-furnace/oxygen-steelmaking route. steel produced in EAFs. Science412-306-4350 and Engineering [email protected] Mellon University Improvements in design, coupled with research For example, we recently used mathematical developments in metallurgy, mean high-quality steel modeling to explore ways to control produced quickly and energy-efficiently. phosphorus. Careful regulation of temperature, slag and stirring are needed to produce low- Not Your (Great-) Grandparent’s EAF phosphorus steel. We analyzed data from Especially since the mid-1990s, there have been operating furnaces and found that, in many significant improvements in the design of EAFs, cases, the phosphorus removal reaction could which allow for better-functioning burners and a proceed further. -

The End of the Queue: Hair As Symbol in Chinese History Michael Godley

East Asian History NUMBER 8 . DECEMBER 1994 THE CONTINUATION OF Paperson Far EasternHistory Institute of Advanced Studies Australian National University Editor Geremie R. Barme Assistant Editor Helen Lo Editorial Board John Clark Mark Elvin (Convenor) Helen Hardacre John Fincher Andrew Fraser Colin Jeffcott W. J. F. Jenner Lo Hui-min Gavan McCormack David Marr Tessa Morris-Suzuki Michael Underdown Business Manager Marion Weeks Production Helen Lo Design Maureen MacKenzie (Em Squared Typographic Design), Helen Lo Printed by Goanna Print, Fyshwick, ACT This is the eighth issue of East Asian History in the series previously entitled Papers on Far Eastern History. The journal is published twice a year. Contributions to The Editor, East Asian History Division of Pacific & Asian History, Research School of Pacific & Asian Studies Australian National University, Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Phone +61 62493140 Fax +61 62495525 Subscription Enquiries Subscription Manager, East Asian History, at the above address Annual Subscription Australia A$45 Overseas US$45 (for two issues) iii CONTENTS 1 Mid-Ch'ing New Text (Chin-wen) Classical Learning and its Han Provenance: the Dynamics of a Tradition of Ideas On-cho Ng 33 From Myth to Reality: Chinese Courtesans in Late-Qing Shanghai Christian Henriot 53 The End of the Queue: Hair as Symbol in Chinese History Michael Godley 73 Broken Journey: Nhfti Linh's "Going to France" Greg and Monique Lockhart 135 Chinese Masculinity: Theorising' Wen' and' Wu ' Kam Louie and Louise Edwards iv Cover calligraphy Yan Zhenqing �JU!iUruJ, Tang calligrapher and statesman Cover picture The walled city of Shanghai (Shanghai xianzhi, 1872) THE END OF THE QUEUE: HAIR AS SYMBOL IN CHINESE HISTORY ..J1! Michael R. -

The White Book of STEEL

The white book of STEEL The white book of steel worldsteel represents approximately 170 steel producers (including 17 of the world’s 20 largest steel companies), national and regional steel industry associations and steel research institutes. worldsteel members represent around 85% of world steel production. worldsteel acts as the focal point for the steel industry, providing global leadership on all major strategic issues affecting the industry, particularly focusing on economic, environmental and social sustainability. worldsteel has taken all possible steps to check and confirm the facts contained in this book – however, some elements will inevitably be open to interpretation. worldsteel does not accept any liability for the accuracy of data, information, opinions or for any printing errors. The white book of steel © World Steel Association 2012 ISBN 978-2-930069-67-8 Design by double-id.com Copywriting by Pyramidion.be This publication is printed on MultiDesign paper. MultiDesign is certified by the Forestry Stewardship Council as environmentally-responsible paper. contEntS Steel before the 18th century 6 Amazing steel 18th to 19th centuries 12 Revolution! 20th century global expansion, 1900-1970s 20 Steel age End of 20th century, start of 21st 32 Going for growth: Innovation of scale Steel industry today & future developments 44 Sustainable steel Glossary 48 Website 50 Please refer to the glossary section on page 48 to find the definition of the words highlighted in blue throughout the book. Detail of India from Ptolemy’s world map. Iron was first found in meteorites (‘gift of the gods’) then thousands of years later was developed into steel, the discovery of which helped shape the ancient (and modern) world 6 Steel bEforE thE 18th cEntury Amazing steel Ever since our ancestors started to mine and smelt iron, they began producing steel. -

Damascus Steel

Damascus steel For Damascus Twist barrels, see Skelp. For the album of blades, and research now shows that carbon nanotubes the same name, see Damascus Steel (album). can be derived from plant fibers,[8] suggesting how the Damascus steel was a type of steel used in Middle East- nanotubes were formed in the steel. Some experts expect to discover such nanotubes in more relics as they are an- alyzed more closely.[6] The origin of the term Damascus steel is somewhat un- certain; it may either refer to swords made or sold in Damascus directly, or it may just refer to the aspect of the typical patterns, by comparison with Damask fabrics (which are in turn named after Damascus).[9][10] 1 History Close-up of an 18th-century Iranian forged Damascus steel sword ern swordmaking. These swords are characterized by dis- tinctive patterns of banding and mottling reminiscent of flowing water. Such blades were reputed to be tough, re- sistant to shattering and capable of being honed to a sharp, resilient edge.[1] Damascus steel was originally made from wootz steel, a steel developed in South India before the Common Era. The original method of producing Damascus steel is not known. Because of differences in raw materials and man- ufacturing techniques, modern attempts to duplicate the metal have not been entirely successful. Despite this, several individuals in modern times have claimed that they have rediscovered the methods by which the original Damascus steel was produced.[2][3] The reputation and history of Damascus steel has given rise to many legends, such as the ability to cut through a rifle barrel or to cut a hair falling across the blade,.[4] A research team in Germany published a report in 2006 re- vealing nanowires and carbon nanotubes in a blade forged A bladesmith from Damascus, ca. -

Iron, Steel and Swords Script - Page 1 Powder Is Difficult

10.4. Crucible Steel 10.4.1 The Making of Crucible Steel in Antiquity Debunking the Myth of "Wootz" Before I start on "wootz" I want to be very clear on how I see this rather confused topic: There never has been a secret about the making of crucible (or "wootz") steel, and there isn't one now. Recipes for making crucible steel were well-known throughout the ages, and they were just as sensible or strange as recipes for making bloomery iron or other things. There are many ways for making crucible steel. If the crucible process worked properly, the steel produced was fully liquid, and it didn't matter much exactly how you made it. If the process did not work well and the steel was only partially molten, i.e. a mixture of liquid cast iron and solid austenite, the product was not good steel. Besides differences in the (always large) carbon concentration, the concentration of impurities might also be different - just like for bloomery steel. This might lead to differences in properties for comparable carbon concentrations, for example the susceptibility to cold shortness or the ability to form a good "watered silk" or "water" pattern. Crucible steel that has been liquid once is relatively homogeneous and slag-free - in contrast to bloomery steel. That is where crucible steel is "better" than bloomery steel. Crucible steel is always high carbon if not ultra-high carbon steel (UHCS). This is generally not so good. However, mixtures that would, for example, have produced 0.8 % carbon steel, a steel optimal for many applications, would not melt at the temperatures available. -

The Significance of Wootz Steel to the History of Materials Science Sharada Srinivasan and S Ranganathan

THE ORIGINS OF IRON AND STEEL MAKING IN THE SOUTHERN INDIAN SUBCONTINENT 1 The significance of wootz steel to the history of materials science Sharada Srinivasan and S Ranganathan Introduction The melting of steel proved to be a challenge in antiquity on account of the high melting point of iron. In the 1740s Benjamin Huntsman successfully developed a technique of producing steel that allowed it to be made on a much larger commercial scale and was credited with the discovery of crucible steel. However, Cyril Stanley Smith brought to wider attention an older tradition of crucible steel from India, i.e. wootz or Damascus steel, which he hailed as one of the four metallurgical achievements of antiquity. Known by its anglicized name, wootz from India has attracted world attention. Not so well known is the fact that the modern edifice of metallurgy and materials science was built on European efforts to unravel the mystery of this steel over the past three centuries. Wootz steel was highly prized across several regions of the world over nearly two millennia and one typical product made of this Indian steel came to be known as the Damascus swords. Figure 1 shows a splendid example of the sword of Tipu Sultan. Wootz steel as an advanced material dominated several landscapes: the geographic, spanning Asia, Europe and the Americas; the historic, stretching over two millennia as maps of nations were redrawn and kingdoms rose and fell; and the literary landscape, as celebrated in myths, legends, poetry, drama, movies and plays in western and eastern languages including Sanskrit, Arabic, Urdu, Japanese, Tamil, Telugu and Kannada. -

STEEL in the CIRCULAR ECONOMY a Life Cycle Perspective CONTENTS

STEEL IN THE CIRCULAR ECONOMY A life cycle perspective CONTENTS Foreword 3 The circular economy 4 Life cycle thinking 6 The life cycle assessment (LCA) approach 8 worldsteel’s LCA methodology and life cycle inventory (LCI) database 10 Sustainability and life cycle assessment 12 LCA in the steel industry 14 LCA by life cycle phase 15 Raw materials and steel production 15 Markets for by-products 16 Manufacturing and use 16 Reuse and remanufacturing 18 Recycling 19 LCA initiatives 20 Regional and global initiatives 21 Market sector initiatives 22 Construction 22 Automotive 24 Packaging 25 End notes 28 Glossary 29 Cover image: Steel staircase, office building, Prague, Czech Republic Design: double-id.com FOREWORD We live in a rapidly changing world with finite resources. Too many legislative bodies around the world At the same time, improvements in standards of living still enact regulations which only affect the “use and eradication of poverty, combined with global phase” of a product’s life, for example water and population growth, exert pressure on our ecosystems. energy consumption for washing machines, energy consumption for a fridge or CO2 emissions whilst As steel is everywhere in our lives and is at the heart driving a vehicle. This focus on the “use phase” can of our sustainable future, our industry is an integral part lead to more expensive alternative lower density of the global circular economy. The circular economy materials being employed but which typically have a promotes zero waste, reduces the amount of materials higher environmental burden when the whole life cycle used, and encourages the reuse and recycling of is considered. -

Yuan Ming Yuan Nei Gong Ze Li

1 Workshop “Chinese Handicraft Regulations: Theory and Application” ρറᠲઔಘᄎشঞࠏ: ᓵፖኔ܂πխഏٰ 3rd International Symposium on Ancient Chinese Books and Records of Science and Technology ϝሞЁ⾥ᡔ㈡䰙Ӯ䆂ⷨ䅼Ӯ March 31 – April 3, 2003 Eberhard-Karls-Universität Tübingen These abstracts are for your personal use. ᴀӮ䆂䆎᭛ᨬ㽕ҙկখӮ㗙ϾҎՓ⫼DŽ Please do not circulate or quote without permission by the authors. 㒣㗙ܕ䆌ˈϡᕫ݀ᓔᓩ⫼DŽ 2 Managing Mobility: Popular Technology, Social Visibility and the Regulation of Riverine Transportation in Eighteenth Century China Grant Alger Abstract This paper provides a case study of how local officials during the Qing sought to regulate the usage of privately constructed handicrafts by focusing on the administration of river boats in Fujian province during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Government officials, I argue, possessed a dual view of river boat operators as both marginal and potentially dangerous social figures and as important economic actors. As a result, officials sought to design regulations that decreased criminality on the rivers and also promoted the convenient flow of goods through the region. This study describe first how during the eighteenth century officials sought to police river boat operators by applying the baojia population registration system to the mobile world of the rivers. This policy included ordering that boats be painted, carved or branded with identifying information to lessen the anonymity of boat operators. Due to the state’s inability to execute fully this policy, however, in the early nineteenth century Fujian’s officials ordered instead the implementation of a boat broker system. This system was designed to enmesh all of the participants in the river transport trade, (boatmen, merchants, and brokers) into a relationship of mutual dependency and control as a way to maximize the regulatory impact over the transport trade while minimizing the need for day-to- day government involvement.