Language Revitalization, Land and Identity in an Enclaved Arab Community in Cyprus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Different Dialects of Arabic Language

e-ISSN : 2347 - 9671, p- ISSN : 2349 - 0187 EPRA International Journal of Economic and Business Review Vol - 3, Issue- 9, September 2015 Inno Space (SJIF) Impact Factor : 4.618(Morocco) ISI Impact Factor : 1.259 (Dubai, UAE) DIFFERENT DIALECTS OF ARABIC LANGUAGE ABSTRACT ifferent dialects of Arabic language have been an Dattraction of students of linguistics. Many studies have 1 Ali Akbar.P been done in this regard. Arabic language is one of the fastest growing languages in the world. It is the mother tongue of 420 million in people 1 Research scholar, across the world. And it is the official language of 23 countries spread Department of Arabic, over Asia and Africa. Arabic has gained the status of world languages Farook College, recognized by the UN. The economic significance of the region where Calicut, Kerala, Arabic is being spoken makes the language more acceptable in the India world political and economical arena. The geopolitical significance of the region and its language cannot be ignored by the economic super powers and political stakeholders. KEY WORDS: Arabic, Dialect, Moroccan, Egyptian, Gulf, Kabael, world economy, super powers INTRODUCTION DISCUSSION The importance of Arabic language has been Within the non-Gulf Arabic varieties, the largest multiplied with the emergence of globalization process in difference is between the non-Egyptian North African the nineties of the last century thank to the oil reservoirs dialects and the others. Moroccan Arabic in particular is in the region, because petrol plays an important role in nearly incomprehensible to Arabic speakers east of Algeria. propelling world economy and politics. -

Memorandum Exploitation of Maronite Properties in Occupied Cyprus 1

Memorandum Exploitation of Maronite Properties in Occupied Cyprus 1. The Maronite Community in Cyprus has a history that goes back many centuries (over 1000 years). The Maronites of Cyprus practice their own Catholic Maronite religion, they have their own Arabic language, although they all are fluent in Greek, they use the Aramaic language in their liturgy and they have their own customs and culture. As an integral part of the people of Cyprus, when Cyprus declared its independence and the 1960 constitutional arrangements were imposed, the Maronite Community chose to belong, for constitutional purposes, to the Greek Cypriot Community. With the first census carried out by the newly established Republic of Cyprus in 1960, there were approximately 2572 Maronites living in Cyprus. 2. The Turkish military invasion of 1974 resulted in the occupation of all the Maronite villages, namely Kormakitis, Asomatos, Ayia Marina and Karpashia. Subsequently, the vast majority of the Maronite Community was displaced from its historical and cultural localities. Today, about 98% of the Community which now number about 6000 are refugees and are located in the areas controlled by the Cyprus Government. Specifically their occupied villages are as follows: • Asomatos: The village lies in the Kyrenia district. It is the second largest Maronite village. Prior to 1974, the inhabitants of Asomatos were nearly seven hundred. Today, only five Maronites live in the village. The Turkish army has established two centers in the village, one of them in the elementary school and the other in several houses. Several storage houses for petrol, food and artilleries have been serving the army in close proximity to the military camps. -

Old Saint George Church in Kormakitis/Koruçam

Old Saint George Church in Kormakitis/Koruçam PROJECT OVERVIEW Start Date: July 2014 End Date: September 2015 Type of intervention: Conservation works Total cost: 195,265 Euro The Maronite Old Saint George Church is located in the village of Kormakitis/Kormacit/Koruçam. The Church was built in the XVI century. The church is in the monastery within the nun’s court. It was the main church of the Maronite community until the early 20th century when it ceded with the building of the new Saint George cathedral. Designs carried out in 2014 by the Maronite Church Committee through a tri-communal team of architects, engineers and quantity surveyor identified the following needs: Structural conservation of the main body of the church (including foundation, walls, floor and vaulted roof); Reconstruction of the belfry; Landscaping. The restoration of the church included the following interventions: Removal of all concrete and cement that had been applied on the original stone structure of the church); Structural conservation on the main body (foundations, walls, floor and vaulted roof) of the church; Upgrade of the courtyard; Provision of proper drainage and protection of the foundations; Removal of terrazzo tiles and installation of Cyprus marble; Restoration of wooden doors which are of exceptional historical and archaeological value; Waterproof roof and foundations; Reconstruction of the bell tower and installation of a new bell; Electrical cabling and wiring; Fittings for electricity; Upgrade of the courtyard and provision of accessibility to persons with disabilities. The project was fully funded by the European Union. Total cost (including works and supervision) 195,265 Euro. -

Considerations for Non-Dominant Language Education in the Global South

FIRE: Forum for International Research in Education Vol. 5, Iss. 3, 2019, pp. 12-28 LANGUAGE-IN-EDUCATION POLICIES AND INDIGENOUS LANGUAGE REVITALIZATION EFFORTS IN CANADA: CONSIDERATIONS FOR NON-DOMINANT LANGUAGE EDUCATION IN THE GLOBAL SOUTH Onowa McIvor1 University of Victoria, Canada Jessica Ball University of Victoria, Canada Abstract Indigenous languages are struggling for breath in the Global North. In Canada, Indigenous language medium schools and early childhood programs remain independent and marginalized. Despite government commitments, there is little support for Indigenous language-in-education policy and initiatives. This article describes an inaugural, country- wide, federally-funded, Indigenous-led language revitalization research project, entitled NE OL EW̱ (one mind-one people). The project brings together nine Indigenous partners to build a country-wide network and momentum to pressure multi-levels of government to honourȾ agreementsṈ enshrining the right of children to learn their Indigenous language. The project is documenting approaches to create new Indigenous language speakers, focusing on adult language learners able to keep the language vibrant and teach their language to children. The article reflects upon how this Northern emphasis on Indigenous language revitalization and country-wide networking initiative is relevant to mother tongue-based education and policy examples in the Global South. The article underscores the need for both community level initiatives (top-down) and government level policy and funding (bottom up) to support child and adult Indigenous language learning. Keywords: Indigenous language practices, language-in-education policies, policy reform, First Nations, Indigenous, Canada, Global North, Global South 1 Correspondence: Dr. Onowa McIvor, C/O Dept. of Indigenous Education, University of Victoria, PO Box 1700 STN CSC, Victoria BC V8W 2Y2; Email: [email protected] O. -

Youth, Technology and Indigenous Language Revitalization in Indonesia

Youth, Technology and Indigenous Language Revitalization in Indonesia Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Putra, Kristian Adi Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction, presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 24/09/2021 19:51:25 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/630210 YOUTH, TECHNOLOGY AND INDIGENOUS LANGUAGE REVITALIZATION IN INDONESIA by Kristian Adi Putra ______________________________ Copyright © Kristian Adi Putra 2018 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the GRADUATE INTERDISCIPLINARY PROGRAM IN SECOND LANGUAGE ACQUISITION AND TEACHING In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2018 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Kristian Adi Putra, titled Youth, Technology and Indigenous Language Revitalization in Indonesia and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. -~- ------+-----,T,___~-- ~__ _________ Date: (4 / 30/2018) Leisy T Wyman - -~---~· ~S:;;;,#--,'-L-~~--~- -------Date: (4/30/2018) 7 Jonath:2:inhardt ---12Mij-~-'-+--~4---IF-'~~~~~"____________ Date: (4 / 30 I 2018) Perry Gilmore Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate' s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement. -

Arabic and Contact-Induced Change Christopher Lucas, Stefano Manfredi

Arabic and Contact-Induced Change Christopher Lucas, Stefano Manfredi To cite this version: Christopher Lucas, Stefano Manfredi. Arabic and Contact-Induced Change. 2020. halshs-03094950 HAL Id: halshs-03094950 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-03094950 Submitted on 15 Jan 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Arabic and contact-induced change Edited by Christopher Lucas Stefano Manfredi language Contact and Multilingualism 1 science press Contact and Multilingualism Editors: Isabelle Léglise (CNRS SeDyL), Stefano Manfredi (CNRS SeDyL) In this series: 1. Lucas, Christopher & Stefano Manfredi (eds.). Arabic and contact-induced change. Arabic and contact-induced change Edited by Christopher Lucas Stefano Manfredi language science press Lucas, Christopher & Stefano Manfredi (eds.). 2020. Arabic and contact-induced change (Contact and Multilingualism 1). Berlin: Language Science Press. This title can be downloaded at: http://langsci-press.org/catalog/book/235 © 2020, the authors Published under the Creative Commons Attribution -

Bishop Porfyrios of Neapolis of the Church of Cyprus

Speech of His Grace Bishop Porfyrios of Neapolis “Religious Freedom in the Republic of Cyprus” at the event: “Human Rights within the European Union” (05-12-2018). In July 1974, as many of you will know, Turkey invaded Cyprus with a large military force, taking advantage of the coup d’état carried out by the military junta in Greece against Archbishop Makarios III, the elected President of the Republic of Cyprus. On August 16, the fighting stopped but 43 years on, the wounds to body of the island have still not healed. Some 37% of its territory remains occupied by the Turkish army, which maintains a force of 40,000 soldiers there. In so doing, it has made Cyprus one of the most heavily militarised places in the world. Some 180,000 Greek Cypriots were expelled from their homes and properties. Today, around 500 remain enclaved in the Karpas peninsula and the Maronite villages. In November 1983, the occupation regime declared the independence of the so-called “Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus”, in a move that was condemned by the United Nations Security Council. No other country, apart from Turkey, has recognised the illegal entity. As a result of the invasion, Christian monuments and those of other faiths, sacred and archaeological sites were desecrated, looted and destroyed. Everything that adorned the 575 Orthodox churches in the occupied areas was stolen. Some 20,000 holy icons, wall paintings, mosaics, gospels, sacred vessels, manuscripts, old books, iconostases and, generally speaking, anything that could be stolen for material gain was looted and sold abroad. -

ENIA) from West to East Along the Besparmak Mountain Range

WALKING FUN – 8 DAYS NORTH CYPRUS (KORMACIT+KYRENIA) From West to East along the Besparmak mountain range SIDE TOURISM & TRAVEL AGENCY LTD. Canbulat Street 7/A ▪ Kyrenia ▪ NORTHERN CYPRUS ▪ Tel: +90 (0) 392 815 3008 ▪ Fax: +90 (0) 392 8151109 ▪ [email protected] ▪ www.side-tour.com DAY 1: Arrival, transfer and light dinner in Kormacit Arrival in Ercan or Larnaca or Paphos. Transfer to the Maronite village of Kormacit. Light dinner and overnight in Kormacit. DAY 2: Walking tour Cap Kormakitis – Kormacit 16km; 6h) Transfer to Sadrazamköy. Linear walking tour Kap Kormakitis – Kormacit (16km; 6h). Overnight in Kormacit http://www.outdooractive.com/en/hiking-trail/walking-cape-kormakitis-kormacit/105427903/ DAY 3: Circular walking tour Kormacit (16 km; 4h30) Circular walking tour Kormacit (16 km; 4h30). Access to a virgin beach. Discover the Maronite village with its mini farm, its two St George churches and its ethnographical museum. Overnight in Kormacit. http://www.outdooractive.com/en/hiking-trail/cyprus/walking-kormacit-round-trail/105427926/ SIDE TOURISM & TRAVEL AGENCY LTD. Canbulat Street 7/A ▪ Kyrenia ▪ NORTHERN CYPRUS ▪ Tel: +90 (0) 392 815 3008 ▪ Fax: +90 (0) 392 8151109 ▪ [email protected] ▪ www.side-tour.com DAY 4: Walking tour Kormacit – Karşıyaka (16km; 6h) Linear walking tour from Kormacit to Karşıyaka (16km; 6h). Passing the monumental dam of Geçitköy, the first valleys of the Besparmak Mountains and the famous tank of 1974. Transfer Karşıyaka – Kyrenia. Overnight in Kyrenia : http://www.outdooractive.com/en/hiking-trail/cyprus/walking-kormacit-kariyaka/105428209/ DAY 5: Walking tour Bellapais – Buffavento Castle (13km; 5h30) Linear walking tour Bellapais – Buffavento Castle (13km ; 5h30). -

Language Revitalization Grade 4

Language Revitalization Grade 4 HEALTH Language Revitalization Overview ESSENTIAL UNDERSTANDINGS • Language This lesson explores the preservation and revital- ization of Indigenous languages—why it’s import- LEARNING OUTCOMES ant and what tribes in Oregon are doing to keep • Students can describe language their ancestral languages alive. This is important for revitalization and identify one or many Native American tribes, who are attempting more revitalization tools or practices. to save their languages from “linguicide” caused • Students can describe why tribes by decades of colonialism and forced assimila- in Oregon want to revitalize and or tion. Language revitalization can help restore and maintain their ancestral languages. strengthen cultural connections and pride, which • Students can connect language revital- in turn can promote well-being for both tribes and ization to restoring cultural pride and the benefits of that pride for group and their members. individual well-being. Background for teachers ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS • What is language revitalization, Language is an essential part of human identity and what are some ways people and shapes how we view the world. For many revitalize languages? Native American tribes, however, language is a • Why do the nine federally recognized complicated and even painful subject. Euro-Amer- tribes in Oregon feel it is important ican government officials, teachers, and other to revitalize and/or maintain their ancestral languages? authorities discouraged Native American and Alaska Native people -

Indigenous Language Revitalization on Social Media During the Early COVID-19 Pandemic

Vol. 15 (2021), pp. 239–266 http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc http://hdl.handle.net/10125/24976 Revised Version Received: 10 Mar 2021 #KeepOurLanguagesStrong: Indigenous Language Revitalization on Social Media during the Early COVID-19 Pandemic Kari A. B. Chew University of Oklahoma Indigenous communities, organizations, and individuals work tirelessly to #Keep- OurLanguagesStrong. The COVID-19 pandemic was potentially detrimental to Indigenous language revitalization (ILR) as this mostly in-person work shifted online. This article shares findings from an analysis of public social media posts, dated March through July 2020 and primarily from Canada and the US, about ILR and the COVID-19 pandemic. The research team, affiliated with the NEȾOL- ṈEW̱ “one mind, one people” Indigenous language research partnership at the University of Victoria, identified six key themes of social media posts concerning ILR and the pandemic, including: 1. language promotion, 2. using Indigenous languages to talk about COVID-19, 3. trainings to support ILR, 4. language ed- ucation, 5. creating and sharing language resources, and 6. information about ILR and COVID-19. Enacting the principle of reciprocity in Indigenous research, part of the research process was to create a short video to share research findings back to social media. This article presents a selection of slides from the video accompanied by an in-depth analysis of the themes. Written about the pandemic, during the pandemic, this article seeks to offer some insights and understandings of a time during which much is uncertain. Therefore, this article does not have a formal conclusion; rather, it closes with ideas about long-term implications and future research directions that can benefit ILR. -

The Damascus Psalm Fragment Oi.Uchicago.Edu

oi.uchicago.edu The Damascus Psalm Fragment oi.uchicago.edu ********** Late Antique and Medieval Islamic Near East (LAMINE) The new Oriental Institute series LAMINE aims to publish a variety of scholarly works, including monographs, edited volumes, critical text editions, translations, studies of corpora of documents—in short, any work that offers a significant contribution to understanding the Near East between roughly 200 and 1000 CE ********** oi.uchicago.edu The Damascus Psalm Fragment Middle Arabic and the Legacy of Old Ḥigāzī by Ahmad Al-Jallad with a contribution by Ronny Vollandt 2020 LAMINE 2 LATE ANTIQUE AND MEDIEVAL ISLAMIC NEAR EAST • NUMBER 2 THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO CHICAGO, ILLINOIS oi.uchicago.edu Library of Congress Control Number: 2020937108 ISBN: 978-1-61491-052-7 © 2020 by the University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 2020. Printed in the United States of America. The Oriental Institute, Chicago THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO LATE ANTIQUE AND MEDIEVAL ISLAMIC NEAR EAST • NUMBER 2 Series Editors Charissa Johnson and Steven Townshend with the assistance of Rebecca Cain Printed by M & G Graphics, Chicago, IL Cover design by Steven Townshend The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Services — Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. ∞ oi.uchicago.edu For Victor “Suggs” Jallad my happy thought oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu Table of Contents Preface............................................................................... ix Abbreviations......................................................................... xi List of Tables and Figures ............................................................... xiii Bibliography.......................................................................... xv Contributions 1. The History of Arabic through Its Texts .......................................... 1 Ahmad Al-Jallad 2. -

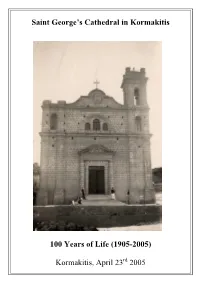

Saint George's Cathedral in Kormakitis 100 Years of Life

Saint George’s Cathedral in Kormakitis 100 Years of Life (1905-2005) Kormakitis, April 23rd 2005 Saint George’s Cathedral in Kormakitis 100 Years of Life (1905-2005) Edition: Saint George’ s Church Committee Of Kormakitis (- 1 -) Writing: Father Antonios Fragkiskou Ioannis Karis Elias Zonias George Foradaris Pictures: - Foradaris’ Foundation - Elias Zonias (- 2 -) CONTENTS Prologue ....................................................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. Salutation from His Beatitude the Archbishop of the Maronites in Cyprus Mr. Petros Gemayiel ...................................................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. Historical Retrospection of the Maronite Community of Cyprus ..... Error! Bookmark not defined. Kormakitis .................................................................................................................... 11 Saint George’s Cathedral ............................................. Error! Bookmark not defined. Chapels and monasteries .............................................................................................. 45 (- 3 -) Prologue This book is published on the occasion of completing 100 years of life of the Saint George’s Cathedral in Kormakitis. It must be noted that this is the only book concerning the said church. The book is explaining the way of which Saint George’s church was built, analyses its role in the history of our community and describes its contents. By entering Kormakitis, every visitor can see the Saint George’s Cathedral.