Imo Edward's Adaptation of the Great Ponds by Elechi Amadi in Performance: a Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Assessment of Radiofrequency Exposure from Base Stations in Some Tertiary Institutions in Rivers State, Nigeria

ISSN (Print): 2476-8316 ISSN (Online): 2635-3490 Dutse Journal of Pure and Applied Sciences (DUJOPAS), Vol. 4 No. 2 December 2018 Assessment of Radiofrequency Exposure from Base Stations in Some Tertiary Institutions in Rivers State, Nigeria *Briggs-Kamara1, M. A., Funsho2, B. I. & Tamunobereton-Ari, I.3 1,2,3Department of Physics, Rivers State University, P.M.B. 5080, Port Harcourt, Rivers State, Nigeria Email: [email protected] Abstract The objective of this research work was to assess the effect of radiofrequency (RF) radiation exposure from Mobile Base Stations, if any, on the Environment. Measurements were carried out using the RF Strength Meter (ALRF05 Model, Toms Gadgets). Six (6) locations with a total number of ten (10) Mobile Base Stations were considered. The minimum and maximum power densities measured ranged between 0.03 μW.cm-2 and 4.094 μW.cm-2 at the Rivers State University, 0.072 μW.cm-2 and 3.239 μW.cm-2 at University of Port Harcourt - Abuja campus, 0.110 μW.cm-2 and 4.204 μW.cm-2 at the Elechi Amadi Polytechnic and 0.112 μW.cm-2 and 2.090 μW.cm-2 at the Ignatius Ajuru University of Education Rumuolumeni Campus. Mobile Base Stations were not sited within the campuses of the Catholic Institution for West Africa (CIWA) and the Eastern Polytechnic Rumuokwurusi (EPR) however, measurements show minimum and maximum power densities which ranged between 0.112 μW.cm-2 and 0.487 μW.cm-2 at CIWA and 0.112 μW.cm-2 and 0.487 μW.cm-2 at EPR. -

As Ethnic Identity in Elechi Amadi's the Concubine

International Journal of English Language and Literature Studies, 2013, 2(1):39-53 International Journal of English Language and Literature Studies journal homepage: http://www.aessweb.com/journal-detail.php?id=5019 “IGBO LINGUISTIC EXPRESSIONS” AS ETHNIC IDENTITY IN ELECHI AMADI’S THE CONCUBINE Joseph A. Ushie Department of English, University of Uyo, Uyo, Nigeria Romanus A. Aboh Department of English, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria ABSTRACT The basic concern of this article is to interpret Elechi Amadi’s novel, The Concubine, as an Igbo novel (i.e., a novel that specifically reflects on the ways of life of the Igbo people of Southeast Nigeria). Relying on insights from sociolinguistics and ethnic studies, the paper analyses select expressions in Igbo, along with ethno-linguistic and cultural features of the people as manifested in the novel. It shows that Amadi’s use of language in The Concubine appears to be a peculiar speech form of the Igbo language. The paper further reveals that the novelist makes conscious use of certain linguistic items in order to express ethnic identity as a way of projecting “Igbo linguistics” and their cultural values as these were before the advent of colonialism. Keywords: Igbo, cultural ethos, colonialism, identity INTRODUCTION There is a significant amount of empirical and theoretical work on the relationship between language and identity (Akindele and Adegbite 1999; Fishman 2001; Harris 2006; Aboh 2012), as well as some important contributions from discourse-religious and socio-historical perspectives (Joseph 2004; Novikoya 2005; Aboh 2010; Jaspal and Coyle 2010; Aboh and Lamidi 2011; Ushie 2012). However, there has been little work on language and ethnic identity particularly on Igbo ethnic identity, one of the largest ethnic majority groups in Nigeria, although some attention has been paid to questions of ethnic identity in general (D e Fina 2007; Jaspal and Coyle 2009; Jaspal and Cinnirella 2012). -

Availability of Material Resources for Educational Delivery in Captain Elechi Amadi Polytechnics Port Harcourt, Rivers State

International Journal of Innovative Social & Science Education Research 7(3):107-114, July-Sept., 2019 © SEAHI PUBLICATIONS, 2019 www.seahipaj.org ISSN: 2360-8978 Availability of Material Resources for Educational Delivery in Captain Elechi Amadi Polytechnics Port Harcourt, Rivers State 1Osuji, Catherine U. (Ph.D) & 2Gbarador, Felix B. Departmental of Educational Foundations Rivers State University, Port Harcourt, Nigeria [email protected] & [email protected] 07036144892 & 08033401574 ABSTRACT This study investigated the availability of material resources for educational delivery in Elechi Amadi Polytechnics Port Harcourt. The study is a descriptive survey research design. The population consisted of 3,857 statistics of students in HND and OND session 2018/2019 and 609 academic/administrative staff total 4,466. A stratified random sampling technique (balloting) was adopted in selecting a sample size of 335 (7.5% of the population size) consisting of 200 students and 135. A 9-item self-structured questionnaire titled “Resources Availability Education Delivery Questionnaire (RAEDQ)” on a modified scale rating was used. The reliability of the instrument was determined via a test re-test method and a Pearson Product Moment Correlation Coefficient of 0.78 was obtained. The mean, standard deviation and rank order statistics were used to answer the research questions while the z-test were used to test the hypotheses at 0.05 level of significance. Findings showed that the availability of instructional facilities enhanced teaching and learning; inadequate instructional facilities affect the strategic planning and that instructional facility facilitates other forms of resources for effective educational delivery. Whereas, recreational facilities such as spaces, lawns, fields, pitches and equipment for sports, games are lacking to promote fitness, leisure time, etc, for students and lecturers. -

ELECHI AMADI's GREAT PONDS and PETROLEUM EXPLOITATION in NIGERIA: the CHALLENGE of RESOURCE CONTROL Abstract

ELECHI AMADI'S GREAT PONDS AND PETROLEUM EXPLOITATION IN NIGERIA: THE CHALLENGE OF RESOURCE CONTROL Prof. A. O. I. Gabriel Abstract The issue of resource pervades Elechi Amadi's Great Ponds and is a big challenge to the Niger Delta People who over the years since petroleum exploitation in the 1950s have struggled for its control. Much revenue is generated from petroleum and most recently gas exploitation just as the Great Ponds, Wagaba Pond in particular is rich with fish that sustains Chiolu village but is poached by others, the Aliakoro in particular. This paper examined the issue of resource control in the two settings and context, and noted that wars or violence is a futile strategy to gaining control but that dialogue, peace and proactive strategies are better. Introduction Every epoch in human history has witnessed some form of struggle for the control of one or a number of natural resources among many human groups or societies. The challenge of resources control and strategies adopted to effect control have varied over time, depending on the ideas of those involved in the controversy and the exigencies of the time. In the pre-colonial period, land, fishing rights over rivers, lands, creeks, control of markets for raw materials, mining rights over salt lakes, and so on provided challenges as to who should control both territories and quantities. In the colonial and post-colonial periods, similar challenges over the control of economic resources such as land, solid minerals, markets, raw materials and so on have been witnessed. Crises and conflicts are often generated in the process particularly as one group tries to dominate the other. -

Capacity Building for Knowledge Management in Selected Academic Libraries in Nigeria

Journal of Library and Information Sciences December 2018, Vol. 6, No. 2, pp. 26-38 ISSN 2374-2372 (Print) 2374-2364 (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development DOI: 10.15640/jlis.v6n2a2 URL: https://doi.org/10.15640/jlis.v6n2a2 Capacity Building for Knowledge Management in Selected Academic Libraries in Nigeria Blessing B. AHIAUZU1, FNLA, CLN & Mercy Ekenma ECHEM2 Abstract The study aimed at ascertaining Capacity Building for Knowledge Management. The main objective of the study was to investigate the level of infrastructure, equipment, source of power supply, personnel and other activities available for knowledge management in those academic institutions in the present ICT age. The eight (8) academic libraries comprising of State and Federal higher institutions in Rivers and Bayelsa States respectively were studied. The study adopted a descriptive survey with a population of 96 which was also the sample size. The data was collected using a simple structured questionnaire and analyzed using simple percentage. The findings revealed that there is need for building adequate and effective capacity for Knowledge Management in all the institutions with their varying needs. Some are challenged within adequate computers, staff access to internet, adequate source of power supply, staff and training needs etc. The study concludes that building adequate and proper capacity for Knowledge Management is vital and necessary because it helps to enhance the quality of service delivery by staff in an effective and efficient manner geared towards achieving the overall goal of the libraries. It recommends that broad band internet bandwidth be provided to address the issue of low internet connectivity; all staff should have free internet access and adequate computers should be made available and maintained, Management of the libraries should ensure adequate personnel and provision for continuous training and re-training of all existing staff for effective and efficient service delivery amongst others. -

Oral Aesthetics and Cultural Distillates in Elechi Amadi's the Concubine

James Tar Tsaaior University of Ibadan Oral aesthetics and cultural distillates in Elechi Amadi’s The Concubine Abstract. The inherent indebtedness of the African novel to the corpus of African oral forms and cultural resources as well as the Western literary tradition has sometimes been unacknowledged and unappreciated. Indeed, the Western metaphysical tradition and philosophical ferment has negated the hybridity of the novel and its African provenance citing its historical, cultural, and regional specificities in the Western hemisphere and literary tradition as contingencies for this seal of negation. Because the rise of the novel is assumed to be consistent with a bourgeois intellectual and scribal culture, Africa is essentially conceptualized as the oral Other and hence lacking in the literary sophistication required to lay claim to the written form. This is the proclamation of the dominant and hegemonic Western epistemological formation. This paper addresses the hybrid heritage of the African novel based on the reality of the fusion of its African oral antecedents and the Western novelistic tradition, using Elechi Amadi’s The Concubine as Exemplum. It argues that African novelists have domesticated the novel form through their exploitation of indigenous oral literary and cultural elements and submits that a thriving relationship exists between the African novel and African folkloric and cultural forms, which gives the African novel its oral flavour, cultural particularity, and authenticity. The paper concludes that rather than construct asymmetrical hierarchical relations between the oral and the written, the two modes of literary expression should be seen as co-eval and complementary to each other, locked in a mutually beneficial and productive interaction as hybrids without which the Western argument will merely be representative of its own cultural politics and essentialisms. -

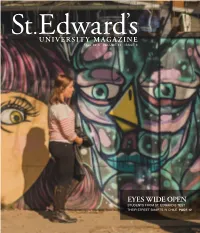

St. Edward's University Magazine Fall 2013 Issue

’ St.EUNIVERSITYdwar MAGAZINEds FALL 2013 VOLUME 13 ISSUE 3 Eyes WIDE OPen STUDENTS FRom ST. EDWARD’S TesT THeiR STReeT smARTS IN CHILE. PAGE 12 12 A StUDY 16 THAT’S BRILLIANT IN CONTRASTS These eight alumni all set their sights Sarah Cardona ’15 traveled to Chile this on something — a school, a backpack, summer with 12 other students from a way to test water and then some St. Edward’s. They explored graffiti-lined — and took action. Here’s how they streets and the beautiful contradictions turned their ideas and visions into of urban Chile. successful ventures. LeTTER FRom THE EDITOR In an attempt to pretend I’m 18 years old instead of in my mid-30s, As I reflected on both the book and the incoming freshmen who I read Half the Sky: Turning Oppression into Opportunity for Women were reading it, I started imaging the change that these students might Worldwide this summer. All of the university’s incoming freshmen read someday inspire. What nonprofits will they create? What diseases will the book, too. they cure? What companies will they start? What solutions will they Half the Sky (see page 3), a thoroughly researched and meticulously present to the world? reported work, chronicles the harrowing conditions women around the In this issue, we bring you a host of stories on alumni, students world face because they’re, well, women. Since I finished the book, I’ve and faculty members who are changing the world in their own ways. been telling everyone who will listen to read it. -

Challenges Faced by Leaders in Improving the Job Performance of Subordinates Dolly C.Kalu

Article https://dx.doi.org/10.4314/iijikm.v9i3.12 Information Impact: Journal of information and Challenges Faced by Leaders in Improving the Job knowledge management Performance of Subordinates 2018, Vol. 9 (3) Pg. 151-160 ISSN: 2141 – 4297 (print) Dolly C. Kalu; Nonyelum P. Okpokwasili & Monday B. Ndor ISSN: 2360 – 994X (e-version) Rivers State University, Nkpolu-Oroworukwo, Port Harcourt, Nigeria. Abstract The major purpose of this study was to determine challenges faced by leaders in improving the job performance of subordinates in academic libraries in Port Harcourt, Rivers State. The research design adopted for the study was a survey. The entire population which consisted of all the 74 professional and Para-professional staff working in the libraries studied also formed the sample size. Data collection was through questionnaire while analysis was done using frequency and means to answer the research question. It can be concluded that the major challenges leaders face in improving job performance of subordinates are that of subordinates not reporting to the leader who delegated authority, high expectations by subordinates from the leader and attitude of subordinates towards the leader. It is recommended among others that subordinates who are delegated to do something should be made to know from the beginning that they should report back to the leader. It is suggested that subsequent researchers can investigating other area such as; Perception of subordinates on the leadership styles adopted by management of various libraries. Keywords; leadership, job performance, subordinates, Port Harcourt, . Introduction A leader is a person who takes the central roles in interaction and who influences the behavior of other members of a group. -

From Rituals to Films: a Case Study of the Visual Rhetoric of Igbo Culture in Nollywood Films

FROM RITUALS TO FILMS: A CASE STUDY OF THE VISUAL RHETORIC OF IGBO CULTURE IN NOLLYWOOD FILMS By Innocent Ebere Uwah, B. Phil, B.Th, P.GD, M.A. A Thesis submitted to Dublin City University, Ireland, for the award of PhD in the Faculty of Humanities Supervisor: Dr Pat Brereton June, 2009 1 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this material, which I now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of the PhD is entirely my own work and has not been taken from the work of others save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. Signed: ID No: 56113161 I.E.Uwah Date: 30th Sept, 2009. 2 ABBREVIATIONS NFVCB – National Film and Video Censors Board FESPACO – Festival Pan Africaine Du Cinema (Festival of Pan African Cinemas) FESPACI – Federation Pan Africaine Des Cineaste (Federation of African Film Makers) CFU – Colonial Film Units FU – Film Unit NFC – Nigerian Film Corporation NFDC – National Film Distribution Company IMF – International Monetary Fund WB -- World Bank SAP -- Structural Adjustment Programme DNA – Deoxyribonucleic acid COMACCO – Compagine Africaine Cinematographique Industrielle et Commerciele SECMA – Societe D’Exploitation Cinematographique Africaine AMPEC – American Motion Picture Export Company AFRAM – Afro-American Film Inc NYSC – National Youth Service Orientation 3 NTA – Nigeria Television Authority VCR – Video Cassette Recorder VHS – Video Home System VCD – Video Compact Disc DVD – Digital Versatile Disc/Digital Video Disc AU – African Union NCC -- Nigeria -

Unbending Gender Narratives in African Literature Charles C

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 8 | Issue 1 Article 10 Nov-2006 Unbending Gender Narratives in African Literature Charles C. Fonchingong Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Fonchingong, Charles C. (2006). Unbending Gender Narratives in African Literature. Journal of International Women's Studies, 8(1), 135-147. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol8/iss1/10 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2006 Journal of International Women’s Studies. Unbending Gender Narratives in African Literature By Charles C. Fonchingong1 Abstract The last century has witnessed an upsurge in literature triggered by the feminist movement. This unprecedented event has transformed the various literary genres that are being deconstructed to suit the changing times. African literature has not been spared by the universalized world order. The paper attempts a re-analysis of gender inequality from the pre-colonial to post-colonial period from the lenses of literary narratives. Male writers like Chinua Achebe, Elechi Amadi, Wole Soyinka, Ngugi Wa Thiongo, and Cyprain Ekwensi in their literary mass are accused of condoning patriarchy, are deeply entrenched in a macho conviviality and a one dimensional and minimalised presentation of women who are demoted and assume peripheral roles. -

The Ignatius Ajuru University and Captain Elechi Amadi Polytechnic Examples

Global Journal of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences Vol.8, No. 1, pp.71-88, January 2020 Published by ECRTD-UK Print ISSN: 2052-6350(Print), Online ISSN: 2052-6369(Online) MITIGATING STAKEHOLDER CONFLICTS IN NIGERIAN TERTIARY INSTITUTIONS: THE IGNATIUS AJURU UNIVERSITY AND CAPTAIN ELECHI AMADI POLYTECHNIC EXAMPLES Daniel Nwanmereni Department of Mass Communication Wellspring University, Benin City, Nigeria Email: [email protected] Phone: +234 - 803 065 6486 ABSTRACT: Several crises in tertiary institutions in Nigeria have been traced to poor policy communication, stakeholders’ rejection of decisions or the management of conflicts. However, while some tertiary institutions in the country often encounter internal crises, the Ignatius Ajuru University of Education and Captain Elechi Amadi Polytechnic have remained relatively calm. This study investigated the communication flow patterns and decision-making approaches of these institutions, especially since conflicts and crises in many campuses in Nigeria have been linked to poor policy communication or disagreements arising from decisions. Among other objectives, the study investigated the structures that encourage participatory decision-making in Ignatius Ajuru University of Education and Captain Elechi Amadi Polytechnic. The study was anchored on the Stakeholder theory. The descriptive survey research design was used to study a population of 21, 089 from which a sample size of 375 was drawn. Findings of the study showed that the authorities of Ignatius Ajuru University of Education -

Culture's Oxygen

CULTURE’S OXYGEN THE PEN REPORT DEVELOPING THE MINORITY-LANGUAGE CREATIVE WRITING INDUSTRY IN KENYA, HAITI, SERBIA AND NIGERIA AN INTER-REGIONAL RESEARCH, ADVOCACY AND DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME TO THE MEMORY OF KEN SARO-WIWA, JNR. (1968–2016) Author and Project Director: Simona Škrabec Editors: Sarah Clarke & James Tennant Copyright © PEN International 2016 Design: Brett Evans Biedscheid Cover Photo: PEN’s Nigeria’s Olúwáfrópò Ewénlá at Port Harcourt Book Festival, 2014 With special thanks to: Moses Kilolo, Ngugi wa Thiong’o, André Brenner, Ronald Blunden, Romana Cacchioli, Ellah Wakatama Allfrey, Ken Saro-Wiwa Jnr, Bibi Bakare-Yusuf, Juno Fitzpatrick, Judy Nwanodi, Tony Enyia, Mark Cowling, Paul Finegan, Jose Borghino, Philip Omorogbe and Hay Festivals. Published by PEN International, with the support of UNESCO’s International Fund for Cultural Diversity PEN International Unit A - Koops Mill Mews 162-164 Abbey Street London SE1 2AN United Kingdom PEN International promotes literature and freedom of expression and is governedby the PEN Charter and the principles it embodies: unhampered transmission of thought within each nation and between all nations. Founded in 1921, PEN International connects an international community of writers from its Secretariat in London. It is a forum where writers meet freely to discuss their work; it is also a voice speaking out for writers silenced in their own countries. Through Centres in over 100 countries, PEN operates on fve continents. PEN International is a non-political organisation which holds Special Consultative Status at the UN and Associate Status at UNESCO. International PEN is a registered charity in England and Wales with registration number 1117088.