Intercultural Dialogue in the Museum Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jelena Bulajic

JELENA BULAJIC Born in 1990, Vrbas, Serbia Lives and works in Serbia and London, UK SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2017 Jelena Bulajic, carlier | gebauer, Berlin, Germany 2016 Collision, Unit 1 Gallery | Workshop, London, UK 2014 Museum Collection of Cultural Centre of Vrbas, Vrbas, Serbia 2013 Old Age Cultural Centre of Belgrade, Belgrade Old Age Likovni Susret Gallery, Subotica 2012 Old Age Nadežda Petrovic Gallery,Cacak Portraits Gallery of the Association of Visual Artists of Vojvodina, Novi Sad 2011 Mladi dolaze Platoneum Gallery, Branch of Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Novi Sad GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2016 Wasted Time, Ferenczy Museum Centre Art Mill, Szentendre, Hungary I Prefer Life, The Weserburg, Bremen, Germany Champagne Life, The Saatchi Gallery, London, UK 2015 New London Figurative, Charlie Smith london, London, UK Summer Exhibition 2015, Royal Academy of Arts, London, UK 2014 Premonition, Blood, Hope: Art in Vojvodina and Serbia 1914 – 2014, Künstlerhaus, Vienna, Austria Saatchi’s New Sensations and The Future Can Wait, Victoria House, London, UK BP Portrait Award 2014, National Portrait Gallery, London, UK. Travelled to Sunderland Museum & Winter Gardens, WWW.SAATCHIGALLERY.COM JELENA BULAJIC Sunderland and Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh, UK The open west 2014, The Wilson Cheltenham Art Gallery & Museum, Cheltenham, UK Culture Escape: Toward a Better World, Galerie Nest, Geneva, Switzerland Young Gods, Charlie Smith london and The Griffin Gallery, London, UK. Curated by Zavier Ellis 2013 Young, Niš Art Foundation Art -

The Differences of Slovenian and Italian Daily Practices Experienced in the First Wave of Covid-19 Pandemic

The Differences of Slovenian and Italian Daily Practices Experienced in the First Wave of Covid-19 Pandemic Saša Pišot ( [email protected] ) Science and Research Centre Koper Boštjan Šimunič Science and Research Centre Koper Ambra Gentile Università degli Studi di Palermo Antonino Bianco Università degli Studi di Palermo Gianluca Lo Coco Università degli Studi di Palermo Rado Pišot Science and Research Centre Koper Patrik Dird Faculty of Sport and Physical Education, University of Novi Sad, Serbia Ivana Milovanović Faculty of Sport and Physical Education, University of Novi Sad, Serbia Research Article Keywords: Physical activity and inactivity behavior, dietary/eating habits, well-being, home connement, COVID-19 pandemic measures Posted Date: June 9th, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-537321/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/18 Abstract Background: The COVID-19 pandemic situation with the lockdown of public life caused serious changes in people's everyday practices. The study evaluates the differences between Slovenia and Italy in health- related everyday practices induced by the restrictive measures during rst wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Methods: The study examined changes through an online survey conducted in nine European countries from April 15-28, 2020. The survey included questions from a simple activity inventory questionnaire (SIMPAQ), the European Health Interview Survey, and some other questions. To compare changes between countries with low and high incidence of COVID-19 epidemic, we examine 956 valid responses from Italy (N=511; 50% males) and Slovenia (N=445; 26% males). -

Novisadoverviewocr.Pdf

Preface The publication Novi Sad, An Overview of The Jevvish Cul- tural Heritage is the first опе of its kind. Ву writing it we vvanted to highlight the impact the Jewry from Novi Sad made while shap- ing the city’s urban and cultural соге. The buildings, streets, monu- ments and sights, hovvever, are just as important as the people who built them and who kept the Jevvish Community together. Over the centuries, Novi Sad along with its Jews had more troublesome than peaceful times, but just like their city, the Jews survived and managed to prosper. TONS, the City’s Tourist Information Centre has supported us in representing the Jevvish Community as a дгоир of individuals made of flesh and blood who, in spite of саггуing the heavy burden of the Holocaust, still have a clear vision while living in harmony with all the other ethnic and cultural groups in Novi Sad. Goran Levi, B.Sc. President of the Jevvish Community HISTORY THE HISTORY OF пате we соте across in the THE JEVVISH archives is the name of Markus Philip and three other families. PEOPLE IN THE Back in 1690 the Jews were VOJVODINA forbidden to live in the bigger REGION AND cities, and over the years that THE CITY OF follovved, they were also forbid- NOVI SAD den to practice certain crafts like making jewelry, stamps, seals According to certain assump- or to get engaged in soap-boil- tions, Jews lived in Vojvodina ing, scrap-iron dealing and to in the centuries even before cultivate the land. These sanc- Christ. -

5 Year Slurry Outlook As of 2021.Xlsx

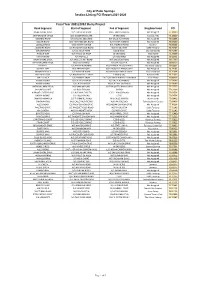

City of Palm Springs Section Listing PCI Report 2021-2026 Fiscal Year 2021/2022 Slurry Project Road Segment Start of Segment End of Segment Neighborhood PCI DINAH SHORE DRIVE W/S CROSSLEY ROAD WEST END OF BRIDGE Not Assigned 75.10000 SNAPDRAGON CIRCLE W/S GOLDENROD LANE W END (CDS) Andreas Hills 75.10000 ANDREAS ROAD E/S CALLE EL SEGUNDO E/S CALLE ALVARADO Not Assigned 75.52638 DILLON ROAD 321'' W/O MELISSA ROAD W/S KAREN AVENUE Not Assigned 75.63230 LOUELLA ROAD S/S LIVMOR AVENUE N/S ANDREAS ROAD Sunmor 75.66065 LEONARD ROAD S/S RACQUET CLUB ROAD N/S VIA OLIVERA Little Tuscany 75.70727 SONORA ROAD E/S EL CIELO ROAD E END (CDS) Los Compadres 75.71757 AMELIA WAY W/S PASEO DE ANZA W END (CDS) Vista Norte 75.78306 TIPTON ROAD N/S HWY 111 S/S RAILROAD Not Assigned 76.32931 DINAH SHORE DRIVE E/S SAN LUIS REY ROAD W/S CROSSLEY ROAD Not Assigned 76.57559 AVENIDA CABALLEROS N/S VISTA CHINO N/S VIA ESCUELA Not Assigned 76.60579 VIA EYTEL E/S AVENIDA PALMAS W/S AVENDA PALOS VERDES The Movie Colony 76.68892 SUNRISE WAY N/S ARENAS ROAD S/S TAHQUITZ CANYON WAY Not Assigned 76.74161 HERMOSA PLACE E/S MISSION ROAD W/S N PALM CANYON DRIVE Old Las Palmas 76.75654 HILLVIEW COVE E/S ANDREAS HILLS DRIVE E END (CSD) Andreas Hills 76.77835 VIA ESCUELA E/S FARRELL DRIVE 130'' E/O WHITEWATER CLUB DRIVE Gene Autry 76.80916 AMADO ROAD E/S CALLE SEGUNDO E/S CALLE ALVARADO Not Assigned 77.54599 AMADO ROAD E/S CALLE ENCILIA W/S CALLE EL SEGUNDO Not Assigned 77.54599 AVENIDA CABALLEROS N/S RAMON ROAD S/S TAHQUITZ CANYON WAY Not Assigned 77.57757 DOLORES COURT LOS -

Programme Case Petrovaradin Small

INTERNATIONAL SUMMER ACADEMY PROGRAMME GUIDE Credits Contents Project organizers Europa Nostra Faculty of sport and Institute for the Welcome note 3 Serbia tourism TIMS protection of cultural monuments Programme overview 4 Partners Detailed programme 5 Public events 9 Practical info 11 Edinburgh World Global observatory on the Europa Nostra Lecturers 12 Heritage historic urban landscape Participants 15 Support Researchers 23 Host team 25 Radio 021 Project funders Foundation NS2021 European Capital of Culture 2 Welcome note Dear Participants, of Petrovaradin Fortress, learn from it and reimagine its future development. We are excited to present you the programme guide and welcome you to the Summer Academy on In this programme guide, we wanted to offer you plenty Managing Historic Urban Landscapes! The Academy is of useful information to get you ready for the upcoming happening at the very important time for the fortress week of the Summer Academy. In the following pages, and the city as a whole. Being awarded both a Youth you can find detailled programme of the week, some and Cultural capital of Europe, Novi Sad is going practical information for your arrival to Petrovaradin through many transformations. Some of these fortress with a map of key locations, and short transformations, including the ones related to the biographies of all the people that will share the same Petrovaradin Fortress, are more structured and place, as well as their knowledge and perspectives thoroughly planned then others. Still, we believe that in during this joint adventure: lecturers, facilitators, Višnja Kisić all of these processes knowledge, experience and participants, researchers and volunteers. -

WG Museums & Creative Industries Study Visit to Serbia from 13 to 15

WG Museums & Creative Industries study visit to Serbia From 13th to 15th of May, 2020 Wednesday, 13th of May – Belgrade Visit of several national museums: National Museum in Belgrade http://www.narodnimuzej.rs/) – presentation of the WG Museums & Creative Industries Museum of Contemporary Art (https://www.msub.org.rs/) Museum of Yugoslavia (https://www.muzej-jugoslavije.org/) – presentation of the Council for Creative Industries – Serbia Creates (under the auspices of the Prime Minister's Cabinet https://www.serbiacreates.rs/) Thursday, 14th of May – Novi Sad Visit to: The Gallery of Matica Srpska (http://www.galerijamaticesrpske.rs/) Museum of Vojvodina (https://www.muzejvojvodine.org.rs/) Foundation ”Novi Sad 2021 – European Capital of Culture” (https://novisad2021.rs/) In the late afternoon departure for Mokrin (accommodation in Mokrin House https://www.mokrinhouse.com/) – we will book the accommodation when we get the exact number of WG members - participants; also, we will check with Mokrin House if there is any possibility to make a discount for the WG members) Friday, 15th of May – Mokrin House 10.00 – 12.00: WG Museum & Creative Industries meeting If there is enough time (it depends on your departure time) visit to the Kikinda National Museum (http://www.muzejkikinda.org.rs/) The end of the study visit – organized transfer from Mokrin/Kikinda to Belgrade or to the airport. Organization: Netork of Euorpean Museum Organisations - NEMO WG Museums & Creative Industries and The Gallery of Matica Srpska with the support of the Council for Creative Industries – Serbia Creates and Foundation ”Novi Sad 2021 – European Capital of Culture”. Accommodation Recommended accommodation (in the city center) you may find on booking.com: Five Points Square – City Center Hotel Savoy Hotel Majestic Or any other accommodation on your choice Accommodation will be in Belgrade (1 or 2 nights) and in Mokrin House (1 night). -

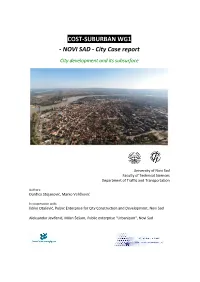

NOVI SAD - City Case Report City Development and Its Subsurface

COST-SUBURBAN WG1 - NOVI SAD - City Case report City development and its subsurface University of Novi Sad Faculty of Technical Sciences Department of Traffic and Transportation Authors: Đurđica Stojanović, Marko Veličković In cooperation with: Ildiko Otašević, Public Enterprise for City Construction and Development, Novi Sad Aleksandar Jevđenić, Milan Šešum, Public enterprise "Urbanizam", Novi Sad Contents 1. Historical development of the city ................................................................. 3 2. City description ............................................................................................. 6 2.1 City location and key data.................................................................................. 6 2.2 Petrovaradin Fortress ........................................................................................ 7 3. Area characteristics ....................................................................................... 9 3.1 Geology .............................................................................................................. 9 3.2 Pedology .......................................................................................................... 11 3.3 Geomorphology ............................................................................................... 13 3.4 Groundwater .................................................................................................... 15 4. Urban infrastructure ................................................................................... -

Journal.Pone.0237608

This is a repository copy of Living off the land : Terrestrial-based diet and dairying in the farming communities of the Neolithic Balkans. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/164722/ Version: Published Version Article: Stojanovski, Darko, Živaljević, Ivana, Dimitrijević, Vesna et al. (16 more authors) (2020) Living off the land : Terrestrial-based diet and dairying in the farming communities of the Neolithic Balkans. PLoS ONE. e0237608. e0237608. ISSN 1932-6203 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0237608 Reuse This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence. This licence allows you to distribute, remix, tweak, and build upon the work, even commercially, as long as you credit the authors for the original work. More information and the full terms of the licence here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ PLOS ONE RESEARCH ARTICLE Living off the land: Terrestrial-based diet and dairying in the farming communities of the Neolithic Balkans 1 1 1,2 3 Darko StojanovskiID *, Ivana Zˇ ivaljevićID , Vesna Dimitrijević , Julie Dunne , Richard P. Evershed3, Marie Balasse4, Adam Dowle5, Jessica Hendy6, Krista McGrath6, 7 6,8 1,2 3 Roman Fischer , Camilla Speller , Jelena JovanovićID , Emmanuelle -

Novi-Sad 2021 Bid Book

CREDITS Published by City of Novi Sad Mayor: Miloš Vučević City Minister of Culutre: Vanja Vučenović Project Team Chairman: Momčilo Bajac, PhD Project Team Members: Uroš Ristić, M.Sc Dragan Marković, M.Sc Marko Paunović, MA Design: Nada Božić Logo Design: Studio Trkulja Photo Credits: Martin Candir KCNS photo team EXIT photo team Candidacy Support: Jelena Stevanović Vuk Radulović Aleksandra Stajić Milica Vukadinović Vladimir Radmanović TABLE OF CONTENT 7 BASIC PRINCIPLES 7 Introducing Novi Sad 9 Why does your city wish to take part in the I competition for the title of European Capital of CONTRIBUTION TO THE Culture? LONG-TERM STRATEGY 14 Does your city plan to involve its surrounding 20 area? Explain this choice. Describe the cultural strategy that is in place in your city at the Explain the concept of the programme which 20 18 time of the application, as well as the city’s plans to strengthen would be launched if the city designated as the capacity of the cultural and creative sectors, including European Capital of Culture through the development of long term links between these sectors and the economic and social sectors in your city. What are the plans for sustaining the cultural activities beyond the year of the title? How is the European Capital of Culture action included in this strategy? 24 If your city is awarded the title of Europian Capital of Culture, II what do you think would be the long-term cultural, social and economic impact on the city (including in terms of urban EUROPEAN development)? DIMENSION 28 25 Describe your plans for monitoring and evaluating the impact of the title on your city and for disseminating the results of the evaluation. -

The Crust (239) 244-8488

8004 TRAIL BLVD THECRUSTPIZZA.NET NAPLES, FL 34108 THE CRUST (239) 244-8488 At The Crust we are committed to providing our guests with delicious food in a clean and friendly environment. Our food is MADE FROM SCRATCH for every order from ingredients that we prepare FRESH in our kitchen EACH DAY. PIZZA Prepared Using Our SIGNATURE HOUSE-MADE Dough – Thin, Crispy, and LIGHTLY SAUCED BUILD YOUR OWN 10 INCH 13 INCH 16 INCH * 12 INCH GLUTEN FREE Cheese .................................. 12.95 Cheese .................................. 16.95 Cheese ................................. 21.75 Cheese .................................. 17.95 Add Topping ......................... 1.10 Add Topping ......................... 2.20 Add Topping ......................... 2.80 Add Topping ......................... 2.20 TOPPINGS SAUCE CHEESE MEAT VEGGIES Marinara Provolone Pepperoni Mushrooms Black Olives Artichokes BBQ Feta Sausage Red Onions Green Olives Garlic Olive Oil Smoked Gouda Meatballs Tomatoes Kalamata Olives Spinach Pesto Gorgonzola Ham Green Peppers Pineapple Cilantro Bacon Banana Peppers Pickled Jalapeños Basil Grilled Chicken Caramelized Onions Anchovies SPECIALTIES 10 INCH ......13 INCH ......16 INCH .........*GF PALERMO .................................................................................................................................................................... 14.95 .......... 19.95 ........ 27.25 ........ 22.95 Olive Oil, Fresh Garlic, Provolone, Parmesan, Gorgonzola, Caramelized Onions BBQ .............................................................................................................................................................................. -

Palermo Open City: from the Mediterranean Migrant Crisis to a Europe Without Borders?

EUROPE AT A CROSSROADS : MANAGED INHOSPITALITY Palermo Open City: From the Mediterranean Migrant Crisis to a Europe Without Borders? LEOLUCA ORLANDO + SIMON PARKER LEOLUCA ORLANDO is the Mayor of Palermo and interview + essay the President of the Association of the Municipali- ties of Sicily. He was elected mayor for the fourth time in 2012 with 73% of the vote. His extensive and remarkable political career dates back to the late 1970s, and includes membership and a break PALERMO OPEN CITY, PART 1 from the Christian Democratic Party; the establish- ment of the Movement for Democracy La Rete (“The Network”); and election to the Sicilian Regional Parliament, the Italian National Parliament, as well as the European Parliament. Struggling against organized crime, reintroducing moral issues into Italian politics, and the creation of a democratic society have been at the center of Oralando’s many initiatives. He is currently campaigning for approaching migration as a matter of human rights within the European Union. Leoluca Orlando is also a Professor of Regional Public Law at the University of Palermo. He has received many awards and rec- ognitions, and authored numerous books that are published in many languages and include: Fede e Politica (Genova: Marietti, 1992), Fighting the Mafia and Renewing Sicilian Culture (San Fran- Interview with Leolucca Orlando, Mayor of Palermo, Month XX, 2015 cisco: Encounter Books, 2001), Hacia una cultura de la legalidad–La experiencia siciliana (Mexico City: Universidad Autonoma Metropolitana, 2005), PALERMO OPEN CITY, PART 2 and Ich sollte der nächste sein (Freiburg: Herder Leoluca Orlando is one of the longest lasting and most successful political lead- Verlag, 2010). -

Wet Meadow Plant Communities of the Alliance Trifolion Pallidi on the Southeastern Margin of the Pannonian Plain

water Article Wet Meadow Plant Communities of the Alliance Trifolion pallidi on the Southeastern Margin of the Pannonian Plain Andraž Carniˇ 1,2 , Mirjana Cuk´ 3 , Igor Zelnik 4 , Jozo Franji´c 5, Ružica Igi´c 3 , Miloš Ili´c 3 , Daniel Krstonoši´c 5 , Dragana Vukov 3 and Željko Škvorc 5,* 1 Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Institute of Biology, 1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia; [email protected] 2 School for Viticulture and Enology, University of Nova Gorica, 5000 Nova Gorica, Slovenia 3 Department of Biology and Ecology, Faculty of Science, University of Novi Sad, 21000 Novi Sad, Serbia; [email protected] (M.C.);´ [email protected] (R.I.); [email protected] (M.I.); [email protected] (D.V.) 4 Department of Biology, Biotechnical Faculty, University of Ljubljana, 1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia; [email protected] 5 Faculty of Forestry, University of Zagreb, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia; [email protected] (J.F.); [email protected] (D.K.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The article deals with wet meadow plant communities of the alliance Trifolion pallidi that appear on the periodically inundated or waterlogged sites on the riverside terraces or gentle slopes along watercourses. These plant communities are often endangered by inappropriate hydrological interventions or management practices. All available vegetation plots representing this vegetation type were collected, organized in a database, and numerically elaborated. This vegetation type appears in the southeastern part of the Pannonian Plain, which is still under the influence of the Citation: Carni,ˇ A.; Cuk,´ M.; Zelnik, Mediterranean climate; its southern border is formed by southern outcrops of the Pannonian Plain I.; Franji´c,J.; Igi´c,R.; Ili´c,M.; and its northern border coincides with the influence of the Mediterranean climate (line Slavonsko Krstonoši´c,D.; Vukov, D.; Škvorc, Ž.