Trento Training School: the Rhetorical Roots of Argumentation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Openagenda: Trento Bets on the Open Data

OPENAGENDA: TRENTO BETS ON THE OPEN DATA Chiara Di Meo, Linguistic and Cultural Mediation for Tourism Business University of Trento, Via Tomaso Gar 14, 38123 Trento, Italy [email protected] Abstract – The work intends to investigate the pattern that Trento Smart City is following in terms of Open Data and Open Government. Among the several projects dealing with such subject, we consider OpenAgenda an ambitious project aiming at the digitization and integration of all relevant information about the cultural and events agenda spread all over the provincial soil. This specific program is to ascribe to the macro-frame of Trento Smart City, as an example of the city’s ongoing technological commitment. OpenAgenda represents an example of how the Province of Trento is betting on technological improvement and advancement by developing and boosting synergies with local partners and surrounding municipalities. Keywords: Trento smart city, open data, open government, ICT, digital agenda, community innovation. I. INTRODUCTION described. Section IV investigates the consequent advantages and challenges deriving from such Nowadays the digital support for the integration and innovative digital turnover and points out the main share of data has reached the primary importance as far rising opportunities. Finally, some conclusions are drawn. as government and governance patterns are concerned. In fact, the implementation of new technologies can II. THE NATIONAL AND THE LOCAL CONTEXTS improve the way the local community access the information and data as well as the way the local The Smart City initiative, based on the use of technology government bodies run their own assignments. This for the improvement of the life-quality standards, is discourse happens to fit particularly well all those framed and included in the 2020 European innovation “minor” municipalities where a change in perspective strategies regarding the “smart” development of urban has already been made: Trento is an example of those contexts in for a sustainable economic and occupational realities. -

The Differences of Slovenian and Italian Daily Practices Experienced in the First Wave of Covid-19 Pandemic

The Differences of Slovenian and Italian Daily Practices Experienced in the First Wave of Covid-19 Pandemic Saša Pišot ( [email protected] ) Science and Research Centre Koper Boštjan Šimunič Science and Research Centre Koper Ambra Gentile Università degli Studi di Palermo Antonino Bianco Università degli Studi di Palermo Gianluca Lo Coco Università degli Studi di Palermo Rado Pišot Science and Research Centre Koper Patrik Dird Faculty of Sport and Physical Education, University of Novi Sad, Serbia Ivana Milovanović Faculty of Sport and Physical Education, University of Novi Sad, Serbia Research Article Keywords: Physical activity and inactivity behavior, dietary/eating habits, well-being, home connement, COVID-19 pandemic measures Posted Date: June 9th, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-537321/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/18 Abstract Background: The COVID-19 pandemic situation with the lockdown of public life caused serious changes in people's everyday practices. The study evaluates the differences between Slovenia and Italy in health- related everyday practices induced by the restrictive measures during rst wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Methods: The study examined changes through an online survey conducted in nine European countries from April 15-28, 2020. The survey included questions from a simple activity inventory questionnaire (SIMPAQ), the European Health Interview Survey, and some other questions. To compare changes between countries with low and high incidence of COVID-19 epidemic, we examine 956 valid responses from Italy (N=511; 50% males) and Slovenia (N=445; 26% males). -

Trento, Bilbao, Finnish Region and Novi Sad Environment V1

Ref. Ares(2016)7134000 - 22/12/2016 A neW concept of pubLic administration based on citizen co-created mobile urban services Grant Agreement: 645845 D3.5 – TRENTO, BILBAO, FINNISH REGION AND NOVI SAD ENVIRONMENT V1 DOC. REFERENCE: WeLive-WP3-D35-REP-211206-v10 RESPONSIBLE: FBK AUTHOR(S): ENG, TECNALIA, UDEUSTO, FBK, CNS, INF, DNET, TRENTO, LAUREA, EUROHELP DATE OF ISSUE: 21/12/16 STATUS: FINAL DISSEMINATION LEVEL: PUBLIC VERSION DATE DESCRIPTION v0.1 11/08/2016 Definition of the Table of Contents and distribution of tasks v0.2 08/11/2016 Contributions from all partners v0.3 29/11/2016 Final version ready to be externally reviewed by BILBAO and TRENTO v1.0 21/12/2016 Reviewers´ comments processed and accepted version submission. INDEX 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY............................................................................................................................................. 6 2. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................................... 7 3. COMMON ENVIRONMENT FOR ALL WELIVE PILOTS ................................................................................................ 9 4. TRENTO ENVIRONMENT ........................................................................................................................................ 10 4.1. PROCESS FOLLOWED IN TRENTO FOR PLATFORM POPULATION ......................................................................... 10 4.1.1. Phase 1 - Stakeholders Consultation Process -

5 Year Slurry Outlook As of 2021.Xlsx

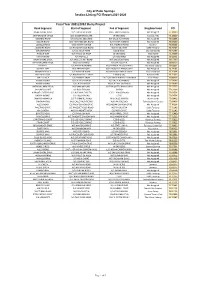

City of Palm Springs Section Listing PCI Report 2021-2026 Fiscal Year 2021/2022 Slurry Project Road Segment Start of Segment End of Segment Neighborhood PCI DINAH SHORE DRIVE W/S CROSSLEY ROAD WEST END OF BRIDGE Not Assigned 75.10000 SNAPDRAGON CIRCLE W/S GOLDENROD LANE W END (CDS) Andreas Hills 75.10000 ANDREAS ROAD E/S CALLE EL SEGUNDO E/S CALLE ALVARADO Not Assigned 75.52638 DILLON ROAD 321'' W/O MELISSA ROAD W/S KAREN AVENUE Not Assigned 75.63230 LOUELLA ROAD S/S LIVMOR AVENUE N/S ANDREAS ROAD Sunmor 75.66065 LEONARD ROAD S/S RACQUET CLUB ROAD N/S VIA OLIVERA Little Tuscany 75.70727 SONORA ROAD E/S EL CIELO ROAD E END (CDS) Los Compadres 75.71757 AMELIA WAY W/S PASEO DE ANZA W END (CDS) Vista Norte 75.78306 TIPTON ROAD N/S HWY 111 S/S RAILROAD Not Assigned 76.32931 DINAH SHORE DRIVE E/S SAN LUIS REY ROAD W/S CROSSLEY ROAD Not Assigned 76.57559 AVENIDA CABALLEROS N/S VISTA CHINO N/S VIA ESCUELA Not Assigned 76.60579 VIA EYTEL E/S AVENIDA PALMAS W/S AVENDA PALOS VERDES The Movie Colony 76.68892 SUNRISE WAY N/S ARENAS ROAD S/S TAHQUITZ CANYON WAY Not Assigned 76.74161 HERMOSA PLACE E/S MISSION ROAD W/S N PALM CANYON DRIVE Old Las Palmas 76.75654 HILLVIEW COVE E/S ANDREAS HILLS DRIVE E END (CSD) Andreas Hills 76.77835 VIA ESCUELA E/S FARRELL DRIVE 130'' E/O WHITEWATER CLUB DRIVE Gene Autry 76.80916 AMADO ROAD E/S CALLE SEGUNDO E/S CALLE ALVARADO Not Assigned 77.54599 AMADO ROAD E/S CALLE ENCILIA W/S CALLE EL SEGUNDO Not Assigned 77.54599 AVENIDA CABALLEROS N/S RAMON ROAD S/S TAHQUITZ CANYON WAY Not Assigned 77.57757 DOLORES COURT LOS -

The Crust (239) 244-8488

8004 TRAIL BLVD THECRUSTPIZZA.NET NAPLES, FL 34108 THE CRUST (239) 244-8488 At The Crust we are committed to providing our guests with delicious food in a clean and friendly environment. Our food is MADE FROM SCRATCH for every order from ingredients that we prepare FRESH in our kitchen EACH DAY. PIZZA Prepared Using Our SIGNATURE HOUSE-MADE Dough – Thin, Crispy, and LIGHTLY SAUCED BUILD YOUR OWN 10 INCH 13 INCH 16 INCH * 12 INCH GLUTEN FREE Cheese .................................. 12.95 Cheese .................................. 16.95 Cheese ................................. 21.75 Cheese .................................. 17.95 Add Topping ......................... 1.10 Add Topping ......................... 2.20 Add Topping ......................... 2.80 Add Topping ......................... 2.20 TOPPINGS SAUCE CHEESE MEAT VEGGIES Marinara Provolone Pepperoni Mushrooms Black Olives Artichokes BBQ Feta Sausage Red Onions Green Olives Garlic Olive Oil Smoked Gouda Meatballs Tomatoes Kalamata Olives Spinach Pesto Gorgonzola Ham Green Peppers Pineapple Cilantro Bacon Banana Peppers Pickled Jalapeños Basil Grilled Chicken Caramelized Onions Anchovies SPECIALTIES 10 INCH ......13 INCH ......16 INCH .........*GF PALERMO .................................................................................................................................................................... 14.95 .......... 19.95 ........ 27.25 ........ 22.95 Olive Oil, Fresh Garlic, Provolone, Parmesan, Gorgonzola, Caramelized Onions BBQ .............................................................................................................................................................................. -

Palermo Open City: from the Mediterranean Migrant Crisis to a Europe Without Borders?

EUROPE AT A CROSSROADS : MANAGED INHOSPITALITY Palermo Open City: From the Mediterranean Migrant Crisis to a Europe Without Borders? LEOLUCA ORLANDO + SIMON PARKER LEOLUCA ORLANDO is the Mayor of Palermo and interview + essay the President of the Association of the Municipali- ties of Sicily. He was elected mayor for the fourth time in 2012 with 73% of the vote. His extensive and remarkable political career dates back to the late 1970s, and includes membership and a break PALERMO OPEN CITY, PART 1 from the Christian Democratic Party; the establish- ment of the Movement for Democracy La Rete (“The Network”); and election to the Sicilian Regional Parliament, the Italian National Parliament, as well as the European Parliament. Struggling against organized crime, reintroducing moral issues into Italian politics, and the creation of a democratic society have been at the center of Oralando’s many initiatives. He is currently campaigning for approaching migration as a matter of human rights within the European Union. Leoluca Orlando is also a Professor of Regional Public Law at the University of Palermo. He has received many awards and rec- ognitions, and authored numerous books that are published in many languages and include: Fede e Politica (Genova: Marietti, 1992), Fighting the Mafia and Renewing Sicilian Culture (San Fran- Interview with Leolucca Orlando, Mayor of Palermo, Month XX, 2015 cisco: Encounter Books, 2001), Hacia una cultura de la legalidad–La experiencia siciliana (Mexico City: Universidad Autonoma Metropolitana, 2005), PALERMO OPEN CITY, PART 2 and Ich sollte der nächste sein (Freiburg: Herder Leoluca Orlando is one of the longest lasting and most successful political lead- Verlag, 2010). -

Martin Huber

Martin Huber Department of Economics, University of Fribourg, Bd. de Pérolles 90, CH-1700 Fribourg, Switzerland Telephone: +41 26 300 82 74 E-mail: [email protected] Fax: +41 26 300 96 78 Date and place of birth: May 06 1980 in Innsbruck, Austria; nationality: Austrian Research interests Policy/treatment effect evaluation in labor, health, and education economics, semi- and nonparametric microeconometric methods for causal inference, machine learning. Academic positions Since 09/2014 University of Fribourg Professor, Chair of Applied Econometrics - Evaluation of Public Policies 02/2010-08/2014 University of St. Gallen Assistant professor of quantitative methods in economics 09/2011-05/2012 Harvard University Visiting researcher (scientific sponsor: Prof. Guido Imbens) 04/2006 -01/2010 Swiss Institute for Empirical Economic Research, University of St. Gallen Research assistant to Prof. Michael Lechner Further work experience 04/2004-03/2006 Employed in private sector companies: Swarovski Crystal Components (strategic marketing) and Transped International (transport logistics) Education 04/2006-01/2010 Ph.D. in Economics and Finance; University of St. Gallen, Switzerland Summa cum laude/with distinction. Specialization: Econometrics; thesis: "Microeconometric Estima- tors and Tests based on Nonparametric Methods, Quantile Regression, and Resampling"; referees: Profs. Michael Lechner, Enno Mammen, and Francesco Audrino 10/1999-02/2004 M.A.s in Economics and in International Business Studies (Mag.rer.soc.oec.); University of Inns- bruck, Austria 09/2001 - 04/2002 Ecole Supérieure de Commerce, Grenoble, France : Erasmus study abroad program Awards and grants 04/2018 Economicus 2017 prize by the foundation “Nadácia VÚB” (Slovakia) for economists below 40 awarded for the joint paper with Lukáš Lafférs and Giovanni Mellace “Sharp IV Bounds on Average Treatment Effects on the Treated and other Populations under Endogeneity and Noncompliance”. -

Thank You All

Thank You All Bernard van Leer Foundation Bertelsmann Vodafone Greece Big Heart Foundation Bestseller Vorwerk We can only accomplish what we do for children, young Canada Feminist Fund British Telecom Western Union Foundation people and families thanks to the generosity, creativity and Dutch Postcode Lottery CEWE White & Case commitment of partners. Partners, both international and Edith & Gotfred Kirk Clarins local, support our ongoing running costs and many of our Fondation de France Deutsche Post DHL Group OTHER PARTNERSHIPS innovative projects. We say thank you to those listed here Fondation de Luxembourg Dr. August Oetker and to the many thousands of other partners who make Grieg Foundation Dufry Group Accountable Now our work possible. Hellenic American Leadership Council Ecoembes Better Care Network Hempel Foundation Fleckenstein Jeanswear Child Rights Connect Institute Circle Foundation 4Life Children’s Rights Action Group Intesa Bank Charity Fund Gekås Ullared Civil Society in Development (CISU) Maestro Cares Foundation GodEl / GoodCause CONCORD INTERGOVERNMENTAL & Government of Germany National Lottery Community Fund Hasbro European Council on Refugees and GOVERNMENTAL PARTNERS Ministry of Foreign Affairs (AA) Novo Nordisk Foundation Herbalife Nutrition Foundation Exiles (ECRE) Federal Ministry for Economic OAK Foundation Hilti EDUCO (International NGO Cooperation Government of Austria Cooperation and Development (BMZ) Obel Family Foundation HSBC for Children) Austrian Development Agency (ADA) Government of Iceland Stiftelsen -

Annual Report 2019

ANNUAL REPORT 2019 SAR Italy is a partnership between Italian higher education institutions and research centres and Scholars at Risk, an international network of higher education institutions aimed at fostering the promotion of academic freedom and protecting the fundamental rights of scholars across the world. In constituting SAR Italy, the governance structures of adhering institutions, as well as researchers, educators, students and administrative personnel send a strong message of solidarity to scholars and institutions that experience situations whereby their academic freedom is at stake, and their research, educational and ‘third mission’ activities are constrained. Coming together in SAR Italy, the adhering institutions commit to concretely contributing to the promotion and protection of academic freedom, alongside over 500 other higher education institutions in 40 countries in the world. Summary Launch of SAR Italy ...................................................................................................................... 3 Coordination and Networking ....................................................................................................... 4 SAR Italy Working Groups ........................................................................................................... 5 Sub-national Networks and Local Synergies ................................................................................ 6 Protection .................................................................................................................... -

Cds.Cern.Ch/Record/2272264?Ln=En

Available on CMS information server CMS CR -2020/039 The Compact Muon Solenoid Experiment Conference Report Mailing address: CMS CERN, CH-1211 GENEVA 23, Switzerland 05 February 2020 (v4, 26 February 2020) Radiation Resistant Innovative 3D Pixel Sensors for the CMS Upgrade at the High Luminosity LHC Marco Meschini for the CMS Collaboration Abstract An extensive R&D program aiming at radiation hard, small pitch, 3D pixel sensors has been put in place between Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare (INFN, Italy) and FBK Foundry (Trento, Italy). The CMS experiment is supporting the R&D in the scope of the Inner Tracker upgrade for the High Luminosity phase of the CERN Large Hadron Collider (HL-LHC). In the HL-LHC the Inner Tracker 16 2 will have to withstand an integrated fluence up to 2:3 × 10 neq=cm . A small number of 3D sensors were interconnected with the RD53A readout chip, which is the first prototype of 65 nm CMOS pixel readout chip designed for the HL-LHC pixel trackers. In this paper results obtained in beam tests before and after irradiation are reported. Irradiation of a single chip module was performed up 16 2 to a maximum equivalent fluence of about 1 × 10 neq=cm . Analysis of the collected data shows excellent performance: spatial resolution in not irradiated (fresh) sensors is about 3 to 5 µm depending on the pixel pitch. Hit detection efficiencies are close to 99% measured both before and after the above mentioned irradiation fluence. Presented at HSTD12 12th International Hiroshima Symposium on the Development and Application of Semiconductor Tracking Detectors (HSTD12) Radiation Resistant Innovative 3D Pixel Sensors for the CMS Upgrade at the High Luminosity LHC M. -

CONDIZIONI GENERALI GRIMALDI LINES Ed.Agosto-21 EN

General Conditions www.grimaldi-lines.com GENERAL CONDITIONS OF CARRIAGE ON GRIMALDI LINES FERRIES - Ed. August/2021 (*) For "Events on board", the General Terms and Conditions apply, as shown at www.grimaldi-touroperator.com . Individual travel programmes can be found at www.grimaldi-lines.com . (**) For "Groups", the General Conditions communicated upon confirmation of the reservation apply. Grimaldi Group S.p.A. acts as agent for the Carrier Grimaldi Euromed S.p.A. The Carrier for the sea leg travelled is indicated on the ticket. Passengers, their luggage and accompanying vehicles are carried according to the Carrier's Terms and Conditions. By purchasing a ticket, the passenger accepts the following Covenants and Conditions. Similarly, at the time of booking and/or purchasing the ticket, the passenger authorises the processing of personal data in the manner specified in the Privacy Policy at the end of this document and in accordance with Italian Legislative Decree 196/2003. 1. DEFINITIONS. Carrier : the operator that performs the maritime transport service; Accompanying vehicle : the motor vehicle (including any towed vehicle) embarked with a passenger, used for the carriage of persons and goods not intended for sale, owned by or legally at the disposal of the passenger named on the ticket; PRM : person whose mobility is reduced, in the use of transport, due to physical disability (sensory or locomotory, permanent or temporary), mental disability or impairment, or any other cause of disability, or due to age, whose condition requires appropriate attention and adaptation of the service to meet specific needs; Service Contract : Concession contract for the public service of maritime transport of passengers, vehicles and goods between Naples, Cagliari, Palermo and vice versa, signed with the Ministry of Infrastructure and Sustainable Mobility; Lines in convention : Naples-Cagliari, Cagliari-Naples, Cagliari-Palermo, Palermo-Cagliari. -

61 Chapter Vii. the Political Development As to The

61 CHAPTER VII. THE POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT AS TO THE STRAITS OF GIBRALTAR DURING AND AFTER THE WAR 1914-1918. A. The political development. " Section 35. The Straits of Gibraltar, the Lighthouse on Cape Spartel and Tangier during the War I9I4-I8. In spite of determined efforts, the Allies did not succeed during the war in effectively barring the Straits of Gibraltar ' z 9I ¢-I 8 since the considerable depth of the Straits rendered effective measures to close them against submarines impossible( I ) . The first German submarine Commander (U 21, Hersing) passed through ' the Straits on May 6th, 1915 to the great amazement of the Allies, who however considered it to be such an isolated case that they hardly strengthened the watch. After that German submarines frequently passed through the Straits which was passed by sub- marines in all up to Nov. I9I8, and these were stationed in the Adriatic. When at the close of October I 9 I 8 the Austrian fleet had to be handed over to the Jugoslav National Council these sub- marines had to make their way home. One had to be interned in Barcelona but of the remaining 1 ¢, 13 succeeded in slipping through the Straits on the night of 8-9th November 1918, and - - only one U 3¢ was sunk outside Ceuta. But the Allies suf- fered still a greater loss since one of the submarines passing through, U 50, sank the English 16.00o tons warship "Britannia" in the Straits on the morning of 9th November(2). Even if they did not succeed in closing the Straits to submarines, the Allies how- " ever completely controlled merchant shipping.