The War Wolf Had Turned Into a Mangy Hound

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Battle of Hastings

The Battle of Hastings The Battle of Hastings is one of the most famous battles in English history. What Caused the Battle? In 1066, three men were fighting to be King of England: William of Normandy, Harold Godwinson and Harald Hardrada. Harold Godwinson was crowned king on 6th January 1066. William and Harald were not happy. They both prepared to invade England in order to kill King Harold and become king themselves. Harald Hardrada attacked from the north of England on 25th September. However, he was killed in battle and his army was defeated by King Harold’s army. King Harold was then told that William of Normandy had landed in the south and was attacking the surrounding countryside. King Harold was furious and marched his tired troops 300 kilometres to meet them. Eight days later, Harold and his men reached London. William sent a messenger to London. The message tried to get Harold to accept William as the true King of England. Harold refused and was angered by William’s request. Harold was advised to wait before attacking William and his army. His troops were very tired and they needed time to prepare for the battle. However, Harold ignored this advice and on 13th October, his troops arrived in Hastings ready to fight. They captured a hill (now known as Battle Hill) and set up a fortress surrounded with sharp stakes stuck in a deep ditch. Harold ordered his forces to stay in their positions no matter what happened. The Battle of Hastings On 14th October, the battle began. -

Saxon Shield Wall Home Learners Pack

Suitable for ages 7-11 KS2 History KS2 English KS2 Art & Design Saxon Shield Wall The Saxons lived in Britain from around 450AD to 1066 when they were over taken by the Normans. The Saxons were fierce warriors and fought in many ferocious battles, against both Vikings and Normans. Their warriors had lots of weapons, such as axes, swords, spears and knives. But they also had protection in the form of helmets, armour and shields. They were in fact famous for using their shields very well, by creating a shield wall. Read on to learn more about Saxon battle tactics. Additional resources Watch a video all about Saxon shield walls on our YouTube channel. Saxon Shield Wall / © Royal Armouries / April 2020 / 1/4 Fascinating Facts How do you make a shield wall? A shield wall is a military tactic. Soldiers line up, shoulder to shoulder and hold their shields in front of them. They stand so close together that their shields overlap. This means that they are protected by their own shield, and by the shields held by the soldiers on either side of them. Image courtesy of Bayeux Museum Types of shield Can you see? The Saxons used 2 different If you look closely at the image you can styles of shield. see that part of the shield wall is The most common type was round. together but there are also a few gaps. They were called ‘trelborg’ shields. What do you think the enemy might do The other type was kite-shaped like the if they saw a gap in the shield wall? ones in the image. -

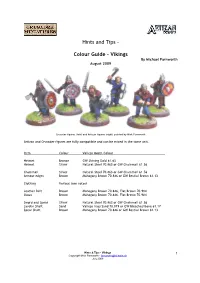

Hints and Tips

Hints and Tips - Colour Guide – Vikings By Michael Farnworth August 2009 Crusader figures (left) and Artizan figures (right) painted by Mick Farnworth Artizan and Crusader figures are fully compatible and can be mixed in the same unit. Item Colour Vallejo Model Colour Helmet Bronze GW Shining Gold 61.63 Helmet Silver Natural Steel 70.863 or GW Chainmail 61.56 Chainmail Silver Natural Steel 70.863 or GW Chainmail 61.56 Armour edges Brown Mahogany Brown 70.846 or GW Bestial Brown 61.13 Clothing Various (see notes) Leather Belt Brown Mahogany Brown 70.846, Flat Brown 70.984 Shoes Brown Mahogany Brown 70.846, Flat Brown 70.984 Sword and Spear Silver Natural Steel 70.863 or GW Chainmail 61.56 Javelin Shaft Sand Vallejo Iraqi Sand 70.819 or GW Bleached Bone 61.17 Spear Shaft Brown Mahogany Brown 70.846 or GW Bestial Brown 61.13 Hints & Tips - Vikings 1 Copyright Mick Farnworth - [email protected] July 2009 Introduction This guide will help you to quickly paint units of Vikings to look good on a war games table. Historical notes, paint references and painting tips are included. Historical Notes Vikings were warriors originating from Scandinavia. The word Viking has many interpretations ranging from voyager to explorer to pirate. Vikings travelled far and wide reaching Greenland and America in the West and Russia and Byzantium in the East. The Viking Age is regarded as starting with raids on Lindisfarne in 789 and ending with the Battle of Stamford Bridge in 1066. Throughout the 9 th and 10 th Centuries Vikings raided England, Ireland, France and Spain. -

The Arms and Armour of 1066

Suitable for ages 11-16 KS3 & KS4 History KS3 & KS4 English The Arms and Armour of 1066 The year 1066 is famous for changing the course of English history. The death of Edward I, also known as Edward the Confessor, caused a succession crisis. Three contenders would fight for the English crown and the right to rule the country. ° Harold Godwinson of Saxon England ° Harald Hardrada of Norway ° William the Duke of Normandy All three believed they had a right to the English throne. In order to fight for the crown they needed armies with weapons, armour and battle tactics. The ensuing epic battles of Fulford, Stamford Bridge and Hastings have earned their place in the history books, and led to William Duke of Normandy becoming King of England. Let’s focus on the Battle of Hastings and have a look at the weapons and armour the warriors used nearly 1,000 years ago. Additional resources Watch a video all about the arms and armour of 1066 on our YouTube channel. Arms & Armour of 1066 / © Royal Armouries / April 2020 / 1/5 The Saxons Axes Types of Saxon warriors Axes were a very common weapon in Europe at that time. Saxon Housecarls are often depicted armed with axes on the Bayeux Tapestry, and the Viking warriors of Hardrada’s army would certainly have wielded them too. This axe head, from our collection, is possibly of Viking origin. These weapons caused a huge amount of damage and injury. The axe head would be mounted on a long handle, between 1.5 and 2 metres in length. -

The Calontir Army Songbook

Under the Shield Wall Words: Chidiock the Younger and Andrixos Seljukroctonis Music: Under the Boardwalk Oh when the sun is hot and your head's burning in your helm, The And though you fight and fight, neither side can overwhelm. Under the shield wall, it's the place to be, With my lady beside me, willingly. (Completely Unofficial) Under the shield wall, where it's quiet and dark, Under the shield wall, like our own private park, Under the shield wall, polearms crashing above, Under the shield wall, we'll be making love, Under the slieldwan, shield wall. Calontir Army Oh it's the sales! place !hal fighter can ever be. No weapon reaches there to break our sweet tranquility, Under the shield wall, out of the sun, Fighters" Authorization With my lady beside me, we'll be havin' fun. • Chorus So when the sides are joined, and you find yourself in the press, Why don't you join me there and take a break from battle strass. Under the shield wall, it's the place to be, With my lady beside me, carnally. Chorus CHOIR A Grazing Mace, I Men of Hartech, I2 Bocephus Song, I7 Navy of Calontir, I2 Calontir Stands Alone, I Non Nobis, 13 Songbook Cheer, 2 None but Calontir-0, 13 Cruiskeen Lawn, 3 Pavel's Song, I4 Drums in my Heart, 4 Ques~ I4 For Crown and For Kingdom, S Raven Banner, IS Fyrdmen on Campaign, 6 Requiem for A Huscart, I6 \ Hal's Song (The man o'war), 4 Song of the Caton Huscart, IS Hamster Song, 7 Song of the Shield Wall, I7 Hit 'em Again, 8 Steel-Shod Dance, I8 Hotspur, 9 Under the Shield Wall, 19 Knighfs Leap, 10 We Be Soldiers Three, 7 Leaving Song, II P ennsic XXX edition 19 A Grazing Mace Cheer Words: Fernando Rodriguez de Falcon and Lyriel de Ia Foret A grazing mace, how sweet the blow That mace has slain ten thousand foes Tune: Bird of Prey March Leslie Rsh That killed a wretch like me. -

Historical Evolution of Roman Infantry Arms And

HISTORICAL EVOLUTION OF ROMAN INFANTRY ARMS AND ARMOR 753 BC - 476 AD An Interactive Qualifying Project Report Submitted to the Faculty of the WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE In partial fulfillment to the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science By Evan Bossio Robert Chase Justin Dyer Stephanie Huang Marmik Patel Nathan Siegel Date: March 2, 2018 Submitted to: Professor Diana A. Lados Professor Luca Capogna Abstract During its time, the Roman Empire gained a formidable reputation as a result of its discipline and organization. The Roman Empire has made a lasting impact on the world due to its culture, political structure, and military might. The purpose of this project was to examine how the materials and processes used to create the weapons and armour helped to contribute to the rise and fall of the Roman Empire. This was done by analyzing how the Empire was able to successfully integrate new technologies and strategies from the regions the Empire conquered. The focus of this project is on the Empire's military, including the organization of the army, and the tactics and weapons used. To better understand the technology and innovations during this time the Roman long sword, spatha, was replicated and analyzed. 1 Acknowledgments The team would like to thank Professor Diana A. Lados and Professor Luca Capogna for this unique experience. The team would also like to thank Anthony Spangenberger for his guidance and time throughout the microstructure analysis. Lastly, this project could not have been done without Joshua Swalec, who offered his workshop, tools, and expertise throughout the manufacturing process 2 Table of Contents Abstract 1 Acknowledgments 2 Table of Contents 3 List of Figures 6 List of Tables 11 Authorship 12 1. -

The Battle of Hastings One of the Most Legendary Battles in English History Was Fought Between the Anglo-Saxons and the Normans and Is Called the Battle of Hastings

The Battle of Hastings One of the most legendary battles in English history was fought between the Anglo-Saxons and the Normans and is called the Battle of Hastings. It took place in Hastings on the south-east of England over 950 years ago and changed the course of English history and culture forever. In January 1066, Edward the Confessor (the English king) was dying. Three men now laid claim to the throne of England: William of Normandy from France; Harold Godwinson from England and Harald Hardrada from Norway. On 6th January, one day after Edward’s death, Harold Godwinson was crowned King of England. As news spread of Harold’s coronation, William and prepared to invade England. They both planned to kill King Harold and claim the throne for themselves. Harald Hardrada invaded first from the north of England on 25th September. However, his army were easily defeated by the Saxons and he himself was killed in battle. King Harold was then informed that William of Normandy had landed in the south of England and was attacking the surrounding countryside. King Harold was furious and marched his exhausted troops 300 kilometres back towards the south to meet him. Eight days later, Harold and his men reached London where they were finally allowed to rest. William sent an envoy to King Harold with a message asking him to hand over the throne and accept William as the true King of England. Harold refused and was angered by William’s treacherous demand. Harold was advised to wait before attacking the Normans. -

The Geographic Origins of the Norman Conquerors of England

The Geographic Origins of the Norman Conquerors of England Christopher Macdonald Hewitt escended from Vikings, the Norman armies of the eleventh and twelfth centuries spread out from their home in Northern France on a quest to conquer and explore new lands beyond their duchy.1 The Dmost famous of these quests was the Norman Conquest of England in 1066. After many months of planning and preparation, this quest climaxed on Saturday, October 14, 1066 at the Battle of Hastings. Here, the Normans crushed the Anglo-Saxon rulers of England with the power and might of their knights. While much has been written about this epic battle, few studies have focused squarely on the importance of some of the more fundamental char- acteristics of the primary combatants themselves—the Norman knights. In an attempt to partially address this deficiency, this study focuses on one particular aspect of this armed cohort: its geographic origins. Following a discussion of Duke William’s leadership role and the Norman Army’s or- ganization at Hastings, the study moves to focus squarely on the as yet un- examined geographical allegiances of the Norman knights and how this might shed light on both the motivation of the combatants and their ulti- mate success in mobilizing the resources required to win at Hastings. Literature review There is no shortage of scholarly work chronicling key aspects of the Battle of Hastings. Temporally, these accounts range from the time of the battle itself until the modern era. One of the oldest and best-known sources is the Bayeux Tapestry. This account depicts the Conquest graphically from the Norman perspective,2 in the form of pictures or diagrams.3 It is be- lieved to have been funded by Bishop Odo of Bayeux, Duke William’s half brother. -

Unconventional Weapons, Siege Warfare, and the Hoplite Ideal

Unconventional Weapons, Siege Warfare, and the Hoplite Ideal Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Masters of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Amanda S. Morton, B.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2011 Thesis Committee: Gregory Anderson, Advisor Timothy Gregory Nathan Rosenstein Copyright by Amanda S. Morton 2011 Abstract This paper examines the introduction of unconventional siege tactics, namely the use of chemical and biological weapons, during the Peloponnesian War in an effort to add to an existing body of work on conventional and unconventional tactics in Greek hoplite warfare. This paper argues that the characteristics of siege warfare in the mid-fifth century exist in opposition to traditional definitions of Greek hoplite warfare and should be integrated into the ongoing discussion on warfare in the fifth century. The use of siege warfare in Greece expanded dramatically during the Peloponnesian War, but these sieges differed from earlier Greek uses of blockade tactics, utilizing fire, poisonous gasses and new types of siege machinery that would eventually lead to a Hellenistic period characterized by inventive and expedient developments in siege warfare. ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank Dr. Gregory Anderson, Dr. Nathan Rosenstein and Dr. Timothy Gregory for their guidance and assistance in the production of this paper. In particular, Dr. Anderson’s patience and guidance in the initial stages of this project were essential to its conception and completion. I would also like to thank Dr. David Staley for his research suggestions and for his encouragements to engage in projects that helped shape my research. -

Brothers in Arms- Final Copy.Docx

Brothers in Arms "Siward, are you alright?" screamed Theobald above all the noise of pain and clashing of swords and shields. “I am trying, Theobald, but what about Eadgar and Alfwold?” I shouted back at him. As we tried to close our shield wall again on Caldbec Hill, we were freezing and frightened. The Normans were closing in on us. Charging with their cavalry, taunting with their spearmen and archers raining their arrows on us, they tried to break our wall. We should never have left our first position. But there were rumours that Duke William had died and those Normans started retreating. In the end, it was all a trick. Luckily I had Theobald close by. “A minute ago, the two of them were fighting in front of us,” Theobald said and gave me his frightened look. “Should we check on them?" "Yes," I said in my most relaxed voice even though I was as deeply troubled as he was. It worked. Theobald relaxed a bit, but when we made our way through the crowds there was panic, fear, screaming and fighting surrounding us. We saw our people falling, badly injured with blood everywhere screaming for our help. Some even trying to grab us. Then all of a sudden, we saw a crowd. I tried to make my way through it. "What happened?" I asked. "The king is down! We are doomed!" a soldier roared. Theobald and I looked at each other in fear. “If we stay, we die” I hissed, grabbed him by his arm and started running. -

Florida State University Libraries

Florida State University Libraries 2016 The Historicity of Homeric Warfare: Battle in the 'Iliad' and the Hoplite Phalanx, c. 750 to 480 BCE Carlos Devin Fernandez Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS & SCIENCES The Historicity of Homeric Warfare: Battle in the Iliad and the Hoplite Phalanx, c. 750 – 480 BCE By CARLOS DEVIN FERNANDEZ A Thesis submitted to the Department of Classics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with Honors in the Major Spring, 2016 2 The members of the Defense Committee approve the thesis of Carlos Devin Fernandez defended on April 19, 2016. 3 Chapter One: Introduction The purpose of this thesis is to examine the nature of battle in Homer’s Iliad, and its relationship to the actual practices of the Archaic period. In particular, it aims to focus on the roles of foot soldiers in Homeric battle, and how their features compare to those of hoplites, who first emerged during the poet’s own era. The renowned epos of war relates the story of Achilles’ wrath against his fellow Greeks during the final year of the Trojan War, and as such, contains innumerable scenes of combat. Though the epic tends to underscore the aristeia (‘excellence’) of its heroes, who are often engaged in single-combat with one another, the same episodes also illustrate the participation of the masses on the battlefield. I shall argue that these scenes of battle, and their representations of infantry combat, when examined with supplementary literary and archaeological evidence, are essential tools in interpreting eighth- to sixth-century BCE warfare, particularly the roles of the average citizen and the development of the hoplite phalanx.1 Background: The Dating of a ‘Homeric Society’ The Iliad has been rigorously analyzed in the resurgence of ancient warfare scholarship over the last few decades. -

Phantasmagoria

Phantasmagoria Spring 2021 To our readers: We as a staff recognize that this year has been new and difficult for everyone. There have been many changes in our lives with online schooling and new classroom requirements. The traditional Tome School Phantasmagoria magazine is no exception to change. We have hit many setbacks in creating this magazine, but we have also grown and adapted just like the Tome School community. This year, our entire magazine is online and in full color! We are also proud to introduce to you our theme which reflects the year that we have experienced together: Darkness to Light Despair to Happiness Bleakness to Hope Similar to how our year began with worries of health and ended with hope because of vaccines, Phantasmagoria shows through not only the content but also the colors how everything may start out bleak, but in the end, everything will be all right. We hope that you enjoy our magazine and thank you for all your support! Phantasmagoria Staff 2021 Phantasmagoria Co-editors: Taylor Fisher Sadie Lewin Staff: Zoe Ebersold J Lucatamo Cavender McCoy Natalie Millham Kaitlyn Mulcahy Logan Price Christina Rasa Jade Tusha Advisors: Mrs. Bohn Mr. Wirdel Front Cover Art: Emily Hubbs Back Cover Art: Katy Bullerman Contributors Melia Abbott (Grade 8) Christina Mulcahy (Grade 8) Katy Bullerman (Grade 9) Kaitlyn Mulcahy (Grade 10) Sam Busseau (Grade 9) Anthony Polizzi (Grade 7) Zoe Ebersold (Grade 11) Logan Price (Grade 9) Madison Hess (Grade 8) Beth Rasa (Grade 8) Emily Hubbs (Grade 10) Christina Rasa (Grade 10) Nellie Hudson (Grade 11) Morgan Reynolds (Grade 8) Cameron Lewandowski (Grade 11) Olivia Russell (Grade 8) Sadie Lewin (Grade 10) Alexis Senn (Grade 10) Andrew Li (Grade 10) Elle Turner (Grade 8) J Lucatamo (Grade 9) Jade Tusha (Grade 10) Ms.