Highlighting Utterances in Chinese Spoken Discourse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SCRS/2020/056 Collect. Vol. Sci. Pap. ICCAT, 77(4): 240-251 (2020)

SCRS/2020/056 Collect. Vol. Sci. Pap. ICCAT, 77(4): 240-251 (2020) 1 REVIEW ON THE EFFECT OF HOOK TYPE ON THE CATCHABILITY, HOOKING LOCATION, AND POST-CAPTURE MORTALITY OF THE SHORTFIN MAKO, ISURUS OXYRINCHUS B. Keller1*, Y. Swimmer2, C. Brown3 SUMMARY Due to the assessed vulnerability for the North Atlantic shortfin mako, Isurus oxyrinchus, ICCAT has identified the need to better understand the use of circle hooks as a potential mitigation measure in longline fisheries. We conducted a literature review related to the effect of hook type on the catchability, anatomical hooking location, and post-capture mortality of this species. We found twenty eight papers related to these topics, yet many were limited in interpretation due to small sample sizes and lack of statistical analysis. In regards to catchability, our results were inconclusive, suggesting no clear trend in catch rates by hook type. The use of circle hooks was shown to either decrease or have no effect on at-haulback mortality. Three papers documented post-release mortality, ranging from 23-31%. The use of circle hooks significantly increased the likelihood of mouth hooking, which is associated with lower rates of post-release mortality. Overall, our review suggests minimal differences in catchability of shortfin mako between hook types, but suggests that use of circle hooks likely results in higher post-release survival that may assist population recovery efforts. RÉSUMÉ En raison de la vulnérabilité évaluée en ce qui concerne le requin-taupe bleu de l'Atlantique Nord (Isurus oxyrinchus), l’ICCAT a identifié le besoin de mieux comprendre l'utilisation des hameçons circulaires comme mesure d'atténuation potentielle dans les pêcheries palangrières. -

Arrowhead Union High School CHALLENGE ROPES COURSE

POLICY: 327. CHALLENGE ROPES COURSE POLICY AND PROCEDURES MANUAL Arrowhead Union High School CHALLENGE ROPES COURSE POLICY AND PROCEDURES MANUAL CREATED BY: Arrowhead Physical Education Department Updated: July, 2008 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Purpose of the Manual 3 Description of the Course 3 Rationale and Philosophy 3-4 Course Location & Physical Function 4 Safety Management 4-5 Requirements of Participants 5 Safety Standards 5- 7 Lead Climbing by instructor 7 - 8 Elements 8 Spotting Techniques 8 - 9 Belaying High Elements 9-10 Double Belay 10 Rescues 10-11 Injuries 11 Blood Born Pathogens Policy 11 PE Staff & Important Telephone Numbers 11 Registration/Release Forms 12 Statement of Health Form/Photo Release 13-14 Set-up Procedures for High Elements on Challenge Course 15-17 3 PURPOSE OF THE MANUAL Literature has been written about the clinical application of ropes and initiative programs. The purpose of this manual is to provide a reference for the technical, mechanical, and task aspects of Arrowhead Target Wellness Challenge Ropes Course & Indoor Climbing Wall Program. Our instructors must speak a common language with respect to setting up, taking down, spotting, belaying, safety practices and methodology, so that these processes remain consistent. Only through this common language will safe use of the course result and full attention be devoted to the educational experience. While variations of tasks are possible and language used to frame the tasks may change, success is always measured by individual and group experience. The technical and mechanical aspects described here represent our Policy, and may only be altered by the Arrowhead Target Wellness Team. -

Human Rights Charter

1 At Treasury Wine Estates Limited (TWE): • We believe that human rights recognise the inherent value of each person and encompass the basic freedoms and protections that belong to every single one of us. Our business and people can only thrive when human rights are safeguarded. • We understand that it’s the diversity of our people that makes us unique and so we want you to be you, because you belong here and you matter. You have a role to play in ensuring a professional and safe working environment where respect for human rights is the cornerstone of our culture and where everyone can make a contribution and feel included. • We are committed to protecting human rights and preventing modern slavery in all its forms, including forced labour and human trafficking, across our global supply chain. We endeavour to respect and uphold the human rights of our people and any other individuals we are in contact with, either directly or indirectly. This Charter represents TWE’s commitment to upholding human rights. HUMAN RIGHTS COMMITMENTS In doing business, we are committed to respecting human rights and support and uphold the principles within the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, the ILO 1998 Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work and Modern Slavery Acts. TWE’s commitment to the protection of human rights and the prevention of modern slavery is underpinned by its global policies and programs, including risk assessment processes that are designed to identify impacts and adopt preventative measures. -

D4 Descender News Feature

The new D4 is an evolutionary development in the world of descenders, a combination of all the best features from other descenders in one. Our market research discovered that many industry users have multiple demands that were not being met by current devices on the market, we listened and let them get involved in the design process of the D4. After hundreds of hours of trials, evaluation and feedback, eventually more than two years later we are proud to release what we, and many dozens of experienced industry users think is the best work/rescue descender in the world! varying speeds but always under control, they need to ascend, they need to create a Z-rig system for progress capture, they need to belay and they need to rescue ideally without having to add components to create friction. Z-rig system with the D4 Work/ Tyrolean Traverse rigging, North Wales. Rescue Descender with ATRAES, Australia. The device needed to work on industry standard ropes of 10.5mm-11.5mm RP880 D4 Descender whether they be dry or wet, new or old, needed to be easy to thread and easy to use, to be robust to the point of being indestructible, and last but Weight > 655g (23oz) not least the device needed to have a double-stop panic brake that engages Slip Load > Approx.5kN > 10.5-11.5mm when you need it to but isn’t so sensitive that it comes on and off too easily. Rope Range User Weight > Up to 240kg (500lbs) It was a tough call. Standards > EN12841; ANSI Z359; NFPA 1983 Page 1 of 4 Features & Applications The D4 has a 240kg/500lb Working Load Limit which means it is absolutely suitable for two-man rescue, without the need for the creation of extra friction. -

The Impact of Mold on Red Hook NYCHA Tenants

The Impact of Mold on Red Hook NYCHA Tenants A Health Crisis in Public Housing OCTOBER 2016 Acknowledgements Participatory Action Research Team Leticia Cancel Shaquana Cooke Bonita Felix Dale Freeman Ross Joy Juana Narvaez Anna Ortega-Williams Marissa Williams With Support From Turning the Tide New York Lawyers for the Public Interest Red Hook Community Justice Center Report Development and Design Pratt Center for Community Development With Funding Support From The Kresge Foundation North Star Fund 2 The Impact of Mold on Red Hook NYCHA Tenants: A Health Crisis in Public Housing Who We Are Red Hook Initiative (RHI) Turning the Tide: A Community-Based RHI is non-profit organization serving the Collaborative community of Red Hook in Brooklyn, New York. RHI is a member of Turning the Tide (T3), a RHI believes that social change to overcome community-based collaborative, led by Fifth systemic inequities begins with empowered Avenue Committee and including Families United youth. In partnership with community adults, we for Racial and Economic Equality, and Southwest nurture young people in Red Hook to be inspired, Brooklyn Industrial Development Corporation. resilient, and healthy, and to envision themselves T3 is focused on engaging and empowering as co-creators of their lives, community and South Brooklyn public housing residents in the society. climate change movement to ensure that the unprecedented public and private-investments We envision a Red Hook where all young for NYCHA capital improvements meet the real people can pursue their dreams and grow into and pressing needs of residents. independent adults who contribute to their families and community. -

Pre-K Attendance Zones 21-22 .Pdf

Katy ISD Prekindergarten Attendance Zones 2021 - 2022 The lists below indicate the prekindergarten attendance zones for the 2021 - 2022 school year. Enrollment at a particular campus is subject to the attendance zone guidelines and space availability. Students who qualify for the prekindergarten program will attend their zoned prekindergarten campus unless the campus no longer has space. Students who qualify for the bilingual program attend campuses on the Bilingual Students list. All other prekindergarten students attend campuses on the ESL/Income/Military/DFPS/Star of Texas Students list. The District will offer students the opportunity to attend a different campus if their zoned campus is full. ESL/INCOME/MILITARY/DFPS/Star of Texas Bilingual Students Students Campus of Students From Campus of Attendance Students From Attendance ACE ACE, JRE, SSE ACE ACE BCE BCE BCE BCE, WE (LUZ 17) BES BES BHE BHE FE FE CBE CBE FES FES and MCE CE CE and FE DWE DWE HE HE, KE, BES (LUZ 8, 20A, 20B, 30, 31B, 40) (N OF I-10) FES FES JWE JWE, CE and RAE FPSE FPSE GE GE MJE MJE, BES (LUZ 50A, 50B, 51A) (S of I-10), HE HE KDE, RJWE and WCE MPE MPE, SCE, JEE, JHE, NCE, PE and WME JEE JEE JHE JHE MRE MRE, DWE (LUZ 24 A-Colony, LUZ 24B- Williams Chase, LUZ 34-Settlement), CBE JRE JRE and OLE, PMCE KE KE Speaking Classes PME PME, GE and RES (LUZ 27C) KDE KDE MCE MCE RES RES (LUZ 14B, 15A, 15B) and WE (LUZ 18) PMCE PMCE RKE RKE and DWE (LUZ 23A, 23B) MGE MGE Spanish MJE MJE RRE RRE, MGE, BHE MRE MRE SE SE Speaking Classes NCE NCE and MPE OKE OKE SES SES and WE (LUZ 39, 48, 49) OLE OLE PE PE? TWE TWE, FPSE, OKE English PME PME USE USE RAE RAE RES RES RJWE RJWE RKE RKE RRE RRE SCE SCE and JWE SE SE SES SES SSE SSE TWE TWE USE USE WCE WCE WE WE WME WME . -

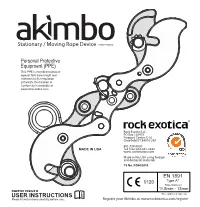

Stationary / Moving Rope Device USER INSTRUCTIONS

Stationary / Movingm Rope Device oPATENT PENDING Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) This PPE is intended to protect against falls from height and conforms to EU regulation 2016/425. Declaration of Conformity is available at www.rockexotica.com ® Rock Exotica LLC PO Box 160470 Freeport Center, E-16 Cleareld UT 84016 USA 801-728-0630 MADE IN USA Toll Free: 844-651-2422 www. rockexotica.com Made in the USA using foreign and domestic materials TS No. RG80/2019 EN 1891 0120 Type A* Rope Diameter: 11.5mm - 13mm RG80500 05/2020 B USER INSTRUCTIONS i *See approved rope list. Read all instructions carefully before use. Register your Akimbo at: www.rockexotica.com/register LEFT SIDE WARNINGS & PRECAUTIONS FOR USE C. Upper Cam D. SRS Chest A. Upper Friction B. Upper Bollard Attachment Adjustment Point (Not for life support) Q. Read user Instructions P. Max. Person i E. Working load Load Limit 1x 130kg O. Upper Control Arm (left) R. 0120 F. Main TS No. RG80/2019 Attatchment M. Rope Size Point N. Upper Lock EN 1891 Type A Arm L. Lower K. Lower Bollard Cam J. Lower Friction Adjustment S. Upper Control Arm (right) WARNING SYMBOLS T. Model Name G. Lower Control Important safety or Arm (left) 1. usage warning H. Manufacture Date: 2. Situation involving risk of injury or death I. Lower Lock Arm Year, Day of Year, Code, Serial Number U. Lower Control TS No. RG80/2019 Arm (right) Notied body controlling the manufacturing of this PPE: SGS United Kingdom Ltd. (CE 0120), 202B Worle Parkway, Weston-super-Mare, BS22 6WA UK. -

Pdf DCHE Brochure

Who We Are New to the Community The Dayton Council on Health Equity (DCHE) is Dayton and Montgomery County’s new local A Closer Look at the Problem office on minority health. As part of Public Health – Dayton & The health of many Americans has steadily declined. Montgomery County, DCHE is Unfortunately, studies show that the health status of four funded by a grant from the Ohio groups in particular – African Americans, Latinos, Asians and Native Americans – has declined much more than the Commission on Minority Health. general population. The goal of DCHE is to improve the health These four groups are experiencing significantly higher of minorities in Montgomery County, rates of certain diseases and conditions, poorer health, loss especially African Americans, of quality of life and a shorter lifespan. These differences Latinos/Hispanics, Asians and are known as “health disparities.” Native Americans. DCHE works with an Advisory Council that includes representatives from many areas: The Diseases and Conditions private citizens, clergy, community groups, DCHE is focusing on chronic, preventable diseases and education and health care organizations, conditions affecting these minority groups, such as: media, city planning and others. The Advisory Council is developing a u Cancer plan to inform, educate and empower u Cardiovascular (heart and blood vessel) disease 117 South Main Street individuals to understand and improve u Diabetes Dayton, Ohio 45422 their health status. u HIV/AIDS 937-225-4962 www.phdmc.org/DCHE u Infant mortality u Substance abuse u Violence Live Better. Live Longer. Good Health Begins with You!® The Good News Simple Steps to Healthier Living Many things are being done to improve the health of minorities. -

Land Is Body, Body Is Land Acknowledgment

Land is Body, Body is Land Acknowledgment Goal x Ǥ Senior 1-4 Education Curriculum Connections This activity contributes to the following Student Specific Learning Outcomes: Aboriginal Languages and Cultures (if offered concurrently with Language Teachings) x 4.1.2 E-10 Give reasons why it is important for contemporary Aboriginal peoples to maintain or re-establish traditional values in their lives. x 4.1.2 F-10 Discuss ways of preserving and transmitting Aboriginal cultural identity. Guidance Education GLOs under Personal/Social Component. Physical and Health Education x K.4.S1.A.1 Examine personal strengths, values, and strategies for achieving individual success. Social Studies (if done specifically with Indigenous youth) x 9.1.4 KI-017 Give examples of ways in which First Nations, Inuit, and Metis people are rediscovering their cultures. x VI-005A Be willing to support the vitality of their First Nations, Inuit, or Métis languages and cultures. (Cross listed under Guidance Education-Personal/Social.) Instructions x Ǥ Note to Facilitators x Ǥ Ǥ Dz ǡdzDzǡdzDz ǡdzDzǤdz 1 200-226 Osborne St. N, Winnipeg, MB R3C 1V4 | 204.784.4010 | www.teentalk.ca | [email protected] | 2019 x Ǧ ǡ ǤǤ Ǥ ǡ ǡ ǡ ǡ Ǥ Visualization Disclaimer “I’m going to ask you to go into your body, to think a little deeply about it for a few minutes so if you don’t want to for any reason, please don’t.” Visualization x “I want you to picture some Land you know. Could be anywhere, could be your backyard, a place you travelled to, your home or even a piece of cement or sidewalk. -

LAWYER Table Contents SUMMER 2011 of Interim Dean MESSAGE from the DEAN

GONZAGA LAWYER Table Contents SUMMER 2011 of Interim Dean MESSAGE FROM THE DEAN . 3 Message the Dean George Critchlow from GEORGE CRITCHLOW Managing Editor Interim Dean Nancy Fike Features LEAD FEATURE - CURRICULUM OVERHAULED . 4 Contributing Writers 100-YEAR STORIES by Gary Randall . 8 Stage Set Virginia deLeon Brooke Ellis Stephen Faust Departments Nancy Fike IN THE NEWS . 10 Jeff Geldien U.S. Attorney Mike Ormsby Sworn In ............................................................................. 10 After two years as interim dean, year. It goes without saying that alumni Washington State Supreme Court Visit .......................................................................... 10 ϐ Ǥ Ailey Kato William O. Douglas Lecture ......................................................................................... 11 Linda McLane Mentoring Program ................................................................................................... 12 ǡ Owen Mooney December Graduation ................................................................................................ 12 ǡ tuition and student debt. Gary Randall Indian Law Lecture ................................................................................................... 13 James E. Rogers College of Law at the ǯ Ǥ Luvera Lecture Series ................................................................................................ 14 University of Arizona. Dean designate Professor Upendra Acharya Addresses Beirut Conference .................................................. -

I'd L Has Passed the Minimum Breaking Strength and Holding Load Test a 1983 (2012 ED.)

® Traceability and markings / Traçabilité et marquage I’D L TRACEABILITY and MARKINGS D20 L 0082 TRACEABILITY : datamatrix = product NFPA 1983 - 2012 ED. 11,5 ≤ ≤ 13 mm reference + individual number e. Serial number EN 12841: 2006 ANSI / ASSE Z359.4 TP TC 019/2011 TRAÇABILITÉ : datamatrix = référence 0082 EN 341: 1997 produit + numéro individuel a. Body controlling the YY M 0000000 000 a. b. j. manufacture of this PPE f. Year of Individual number b. Notified body that carried manufacture k. out the CE type examination (EN) Self-braking descender / belay device Numéro individuel g. Month of Apave Sudeurope SAS manufacture l. Individuelle Nummer 8 rue Jean-Jacques Vernazza (FR) Descendeur assureur autofreinant Z.A.C. Saumaty-Séon - CS 60193 h. Lot number Numero individale 13322 MARSEILLE CEDEX CEDEX 16 Numero individual N°0082 c. e. i. Individual identifier d. c. Traceability: datamatrix = product reference 00 000 AA 0000 0082 + individual number j. Standards Year of Body controlling the manufacturing Notified body intervening for the CE k. Carefully read d. Rope diameter the instructions for use manufacture of this PPE type examination WARNING PETZL.COM Année de fabrication Organisme contrôlant la fabrication de Organisme notifié intervenant pour Herstellungsjahr k.l. Model identification Latest Other Technical PPE cet EPI l’examen CE de type Activities involving the use of this equipment are inherently dangerous. version languages tips checking Anno di fabbricazione Organisation, die die Herstellung Zertifizierungsorganisation für die You are responsibleEN for your 12841 own actions and decisions. Año de fabricación dieser PSA kontrolliert CE-Typenüberprüfung Before using this equipment, you must:2006 Production date Organismo che controlla la Ente riconosciuto che interviene per - Read and understandEN all Instructions12841 : for Use. -

Ihour Booklet

iHour My Starting Hour DzǤ ǡǡ ǡǤdzȂ Aristotle. Habit Routine Schedules How do you feel when you read those three words? Unfortunately, many of us think that habits, routines and schedules are boring, monotonous and they take away spontaneity and freedom from our lives. However, all the great mentors and leaders amongst us abide by these ǥ Stephen King starts the morning with a cup of tea then sits down to work between 8:00 and 8:30 in the same seat with his papers arranged on his desk in the same way. He likes the consistency. Winston Churchill would rise at 7:30 and stay in bed, have breakfast, read the papers and dictate to his assistant until 11:00 ǯ weak whisky and soda after a walk. (Hey, whatever works!) Tony Robbins has the Hour of Power Robin Sharma recommends his Holy Hour Brian Tracey coined the Golden Hour & Eben Pagan calls his the Power Hour Yes we are all different.. We want different things, our challenges are different and our circumstances are certainly different. But basic human needs are the same and our nervous system and bodies function basically the same way. Successful people have daily rituals, it takes choice out of the way and makes it easier to achieve excellence. My iHour What's the iHour and why "i" Hour? We all have a morning ritual which helps us to prepare for the day. My belief is that when you make a routine a habit, it becomes automatic. I call my first morning hour, my "i" hour, because this is the hour that is dedicated to me.