Arxiv:2104.04742V2 [Quant-Ph] 13 Apr 2021 Keywords: Quantum Cryptography, Remote State Preparation, Zero-Knowledge, Learning with Errors Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Randomness Complexity of Interactive Proofs and Statistical Zero-Knowledge Proofs*

On the Randomness Complexity of Interactive Proofs and Statistical Zero-Knowledge Proofs* Benny Applebaum† Eyal Golombek* Abstract We study the randomness complexity of interactive proofs and zero-knowledge proofs. In particular, we ask whether it is possible to reduce the randomness complexity, R, of the verifier to be comparable with the number of bits, CV , that the verifier sends during the interaction. We show that such randomness sparsification is possible in several settings. Specifically, unconditional sparsification can be obtained in the non-uniform setting (where the verifier is modelled as a circuit), and in the uniform setting where the parties have access to a (reusable) common-random-string (CRS). We further show that constant-round uniform protocols can be sparsified without a CRS under a plausible worst-case complexity-theoretic assumption that was used previously in the context of derandomization. All the above sparsification results preserve statistical-zero knowledge provided that this property holds against a cheating verifier. We further show that randomness sparsification can be applied to honest-verifier statistical zero-knowledge (HVSZK) proofs at the expense of increasing the communica- tion from the prover by R−F bits, or, in the case of honest-verifier perfect zero-knowledge (HVPZK) by slowing down the simulation by a factor of 2R−F . Here F is a new measure of accessible bit complexity of an HVZK proof system that ranges from 0 to R, where a maximal grade of R is achieved when zero- knowledge holds against a “semi-malicious” verifier that maliciously selects its random tape and then plays honestly. -

Interactive Proofs

Interactive proofs April 12, 2014 [72] L´aszl´oBabai. Trading group theory for randomness. In Proc. 17th STOC, pages 421{429. ACM Press, 1985. doi:10.1145/22145.22192. [89] L´aszl´oBabai and Shlomo Moran. Arthur-Merlin games: A randomized proof system and a hierarchy of complexity classes. J. Comput. System Sci., 36(2):254{276, 1988. doi:10.1016/0022-0000(88)90028-1. [99] L´aszl´oBabai, Lance Fortnow, and Carsten Lund. Nondeterministic ex- ponential time has two-prover interactive protocols. In Proc. 31st FOCS, pages 16{25. IEEE Comp. Soc. Press, 1990. doi:10.1109/FSCS.1990.89520. See item 1991.108. [108] L´aszl´oBabai, Lance Fortnow, and Carsten Lund. Nondeterministic expo- nential time has two-prover interactive protocols. Comput. Complexity, 1 (1):3{40, 1991. doi:10.1007/BF01200056. Full version of 1990.99. [136] Sanjeev Arora, L´aszl´oBabai, Jacques Stern, and Z. (Elizabeth) Sweedyk. The hardness of approximate optima in lattices, codes, and systems of linear equations. In Proc. 34th FOCS, pages 724{733, Palo Alto CA, 1993. IEEE Comp. Soc. Press. doi:10.1109/SFCS.1993.366815. Conference version of item 1997:160. [160] Sanjeev Arora, L´aszl´oBabai, Jacques Stern, and Z. (Elizabeth) Sweedyk. The hardness of approximate optima in lattices, codes, and systems of linear equations. J. Comput. System Sci., 54(2):317{331, 1997. doi:10.1006/jcss.1997.1472. Full version of 1993.136. [111] L´aszl´oBabai, Lance Fortnow, Noam Nisan, and Avi Wigderson. BPP has subexponential time simulations unless EXPTIME has publishable proofs. In Proc. -

Is It Easier to Prove Theorems That Are Guaranteed to Be True?

Is it Easier to Prove Theorems that are Guaranteed to be True? Rafael Pass∗ Muthuramakrishnan Venkitasubramaniamy Cornell Tech University of Rochester [email protected] [email protected] April 15, 2020 Abstract Consider the following two fundamental open problems in complexity theory: • Does a hard-on-average language in NP imply the existence of one-way functions? • Does a hard-on-average language in NP imply a hard-on-average problem in TFNP (i.e., the class of total NP search problem)? Our main result is that the answer to (at least) one of these questions is yes. Both one-way functions and problems in TFNP can be interpreted as promise-true distri- butional NP search problems|namely, distributional search problems where the sampler only samples true statements. As a direct corollary of the above result, we thus get that the existence of a hard-on-average distributional NP search problem implies a hard-on-average promise-true distributional NP search problem. In other words, It is no easier to find witnesses (a.k.a. proofs) for efficiently-sampled statements (theorems) that are guaranteed to be true. This result follows from a more general study of interactive puzzles|a generalization of average-case hardness in NP|and in particular, a novel round-collapse theorem for computationally- sound protocols, analogous to Babai-Moran's celebrated round-collapse theorem for information- theoretically sound protocols. As another consequence of this treatment, we show that the existence of O(1)-round public-coin non-trivial arguments (i.e., argument systems that are not proofs) imply the existence of a hard-on-average problem in NP=poly. -

DRAFT -- DRAFT -- Appendix

Appendix A Appendix A.1 Probability theory A random variable is a mapping from a probability space to R.Togivean example, the probability space could be that of all 2n possible outcomes of n tosses of a fair coin, and Xi is the random variable that is 1 if the ith toss is a head, and is 0 otherwise. An event is a subset of the probability space. The following simple bound —called the union bound—is often used in the book. For every set of events B1,B2,...,Bk, k ∪k ≤ Pr[ i=1Bi] Pr[Bi]. (A.1) i=1 A.1.1 The averaging argument We list various versions of the “averaging argument.” Sometimes we give two versions of the same result, one as a fact about numbers and one as a fact about probability spaces. Lemma A.1 If a1,a2,...,an are some numbers whose average is c then some ai ≥ c. Lemma A.2 (“The Probabilistic Method”) If X is a random variable which takes values from a finite set and E[X]=μ then the event “X ≥ μ” has nonzero probability. Corollary A.3 If Y is a real-valued function of two random variables x, y then there is a choice c for y such that E[Y (x, c)] ≥ E[Y (x, y)]. 403 DRAFT -- DRAFT -- DRAFT -- DRAFT -- DRAFT -- 404 APPENDIX A. APPENDIX Lemma A.4 If a1,a2,...,an ≥ 0 are numbers whose average is c then the fraction of ai’s that are greater than (resp., at least) kc is less than (resp, at most) 1/k. -

Combinatorial Topology and Distributed Computing Copyright 2010 Herlihy, Kozlov, and Rajsbaum All Rights Reserved

Combinatorial Topology and Distributed Computing Copyright 2010 Herlihy, Kozlov, and Rajsbaum All rights reserved Maurice Herlihy Dmitry Kozlov Sergio Rajsbaum February 22, 2011 DRAFT 2 DRAFT Contents 1 Introduction 9 1.1 DecisionTasks .......................... 10 1.2 Communication.......................... 11 1.3 Failures .............................. 11 1.4 Timing............................... 12 1.4.1 ProcessesandProtocols . 12 1.5 ChapterNotes .......................... 14 2 Elements of Combinatorial Topology 15 2.1 Theobjectsandthemaps . 15 2.1.1 The Combinatorial View . 15 2.1.2 The Geometric View . 17 2.1.3 The Topological View . 18 2.2 Standardconstructions. 18 2.3 Chromaticcomplexes. 21 2.4 Simplicial models in Distributed Computing . 22 2.5 ChapterNotes .......................... 23 2.6 Exercises ............................. 23 3 Manifolds, Impossibility,DRAFT and Separation 25 3.1 ManifoldComplexes ....................... 25 3.2 ImmediateSnapshots. 28 3.3 ManifoldProtocols .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 34 3.4 SetAgreement .......................... 34 3.5 AnonymousProtocols . .. .. .. .. .. .. 38 3.6 WeakSymmetry-Breaking . 39 3.7 Anonymous Set Agreement versus Weak Symmetry Breaking 40 3.8 ChapterNotes .......................... 44 3.9 Exercises ............................. 44 3 4 CONTENTS 4 Connectivity 47 4.1 Consensus and Path-Connectivity . 47 4.2 Consensus in Asynchronous Read-Write Memory . 49 4.3 Set Agreement and Connectivity in Higher Dimensions . 53 4.4 Set Agreement and Read-Write memory . 59 4.4.1 Critical States . 63 4.5 ChapterNotes .......................... 64 4.6 Exercises ............................. 64 5 Colorless Tasks 67 5.1 Pseudospheres .......................... 68 5.2 ColorlessTasks .......................... 72 5.3 Wait-Free Read-Write Memory . 73 5.3.1 Read-Write Protocols and Pseudospheres . 73 5.3.2 Necessary and Sufficient Conditions . 75 5.4 Read-Write Memory with k-Set Agreement . -

List of My Favorite Publications

List of my favorite publications in order of my personal preference with clickable links L´aszl´oBabai April 11, 2014 [35] L´aszl´o Babai. Monte Carlo algorithms in graph isomorphism testing. Tech. Rep. 79{10, Universit´ede Montr´eal,1979. URL http://people.cs.uchicago.edu/~laci/ lasvegas79.pdf. 42 pages. [53] L´aszl´oBabai. On the order of uniprimitive permutation groups. Ann. of Math., 113(3): 553{568, 1981. URL http://www.jstor.org/stable/2006997. [59] L´aszl´oBabai. On the order of doubly transitive permutation groups. Inventiones Math., 65(3):473{484, 1982. doi:10.1007/BF01396631. [114] L´aszl´oBabai. Vertex-transitive graphs and vertex-transitive maps. J. Graph Theory, 15 (6):587{627, 1991. doi:10.1002/jgt.3190150605. [72] L´aszl´oBabai. Trading group theory for randomness. In Proc. 17th STOC, pages 421{429. ACM Press, 1985. doi:10.1145/22145.22192. [89] L´aszl´oBabai and Shlomo Moran. Arthur-Merlin games: A randomized proof system and a hierarchy of complexity classes. J. Comput. System Sci., 36(2):254{276, 1988. doi:10.1016/0022-0000(88)90028-1. [99] L´aszl´oBabai, Lance Fortnow, and Carsten Lund. Nondeterministic exponential time has two-prover interactive protocols. In Proc. 31st FOCS, pages 16{25. IEEE Comp. Soc. Press, 1990. doi:10.1109/FSCS.1990.89520. See item 1991.108. [108] L´aszl´o Babai, Lance Fortnow, and Carsten Lund. Nondeterministic exponential time has two-prover interactive protocols. Comput. Complexity, 1(1):3{40, 1991. doi:10.1007/BF01200056. Full version of 1990.99. [65] L´aszl´o Babai, Peter J. -

Lecture 14 1 Admin 2 Theorems Vs. Proofs 3 Interactive Proof

6.841 Advanced Complexity Theory Mar 30, 2009 Lecture 14 Lecturer: Madhu Sudan Scribe: Huy Nguyen 1 Admin The topics for today are: • Interactive proofs • The complexity classes IP and AM Please see Madhu if you have not been assigned a project. 2 Theorems vs. Proofs There is a long history of the notions theorems and proofs and the relation between them. The question about the meaning of these notions is implicit in Hilbert's program, where he asked if you could prove theorems in various general contexts. Then in Godel's work, he proved that no logic system can be both complete and consistent. The notion of P and NP came along also from the investigation of this relation, as evident in the title of Cook's paper \The complexity of theorem-proving procedures" [2]. In the early works, a system of logic consists of a set of axioms and the derivation rules. A theorem is just a string of characters. The axioms are the initial true statements and the derivation rules show how to get new true statements from existing ones. A proof is a sequence of strings where each string is a either an axiom or derived from previous ones by derivation rules. The final string of the proof should be the derived theorem. In computational complexity, we abstract this procedure away. Theorems are statements that have proofs such that the pair (theorem, proof) is easy to verify. With this abstraction, we have separated the theorem from the proof. Intuitively, the complexity class P is roughly equivalent to the complexity of verifying proofs, while the complexity class NP is roughly equivalent to the complexity of finding proofs. -

Proofs of Proximity for Distribution Testing

Electronic Colloquium on Computational Complexity, Report No. 155 (2017) Proofs of Proximity for Distribution Testing Alessandro Chiesa Tom Gur [email protected] [email protected] UC Berkeley UC Berkeley October 12, 2017 Abstract Distribution testing is an area of property testing that studies algorithms that receive few samples from a probability distribution D and decide whether D has a certain property or is far (in total variation distance) from all distributions with that property. Most natural properties of distributions, however, require a large number of samples to test, which motivates the question of whether there are natural settings wherein fewer samples suffice. We initiate a study of proofs of proximity for properties of distributions. In their basic form, these proof systems consist of a tester (or verifier) that not only has sample access to a distribution but also explicit access to a proof string that depends arbitrarily on the distribution. We refer to these as NP distribution testers, or MA distribution testers if the tester is a probabilistic algorithm. We also study IP distribution testers, a more general notion where the tester interacts with an all-powerful untrusted prover. We investigate the power and limitations of proofs of proximity for distributions and chart a landscape that, surprisingly, is significantly different from that of proofs of proximity for functions. Our main results include showing that MA distribution testers can be quadratically stronger than standard distribution testers, but no stronger than that; in contrast, IP distribution testers can be exponentially stronger than standard distribution testers, but when restricted to public coins they can be quadratically stronger at best. -

Bfm:978-3-540-31691-6/1.Pdf

Lecture Notes in Computer Science 3580 Commenced Publication in 1973 Founding and Former Series Editors: Gerhard Goos, Juris Hartmanis, and Jan van Leeuwen Editorial Board David Hutchison Lancaster University, UK Takeo Kanade Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA, USA Josef Kittler University of Surrey, Guildford, UK Jon M. Kleinberg Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA Friedemann Mattern ETH Zurich, Switzerland John C. Mitchell Stanford University, CA, USA Moni Naor Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel Oscar Nierstrasz University of Bern, Switzerland C. Pandu Rangan Indian Institute of Technology, Madras, India Bernhard Steffen University of Dortmund, Germany Madhu Sudan Massachusetts Institute of Technology, MA, USA Demetri Terzopoulos New York University, NY, USA Doug Tygar University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA Moshe Y. Vardi Rice University, Houston, TX, USA Gerhard Weikum Max-Planck Institute of Computer Science, Saarbruecken, Germany Luís Caires Giuseppe F. Italiano Luís Monteiro Catuscia Palamidessi Moti Yung (Eds.) Automata, Languages and Programming 32nd International Colloquium, ICALP 2005 Lisbon, Portugal, July 11-15, 2005 Proceedings 13 Volume Editors Luís Caires Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Departamento de Informatica 2829-516 Caparica, Portugal E-mail: [email protected] Giuseppe F. Italiano Universitá di Roma “Tor Vergata” Dipartimento di Informatica, Sistemi e Produzione Via del Politecnico 1, 00133 Roma, Italy E-mail: [email protected] Luís Monteiro Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Departamento -

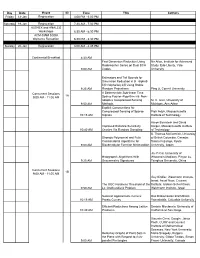

SODA08 Schedule

Day Date Event ID Time Title Authors Friday 18-Jan Registration 4:00 PM - 6:00 PM Saturday 19-Jan Registration 7:30 AM - 7:00 PM ALENEX and ANALCO Workshops 8:30 AM - 6:30 PM ACM-SIAM SODA Welcome Reception 6:30 PM - 8:30 PM Sunday 20-Jan Registration 8:00 AM - 4:45 PM Continental Breakfast 8:30 AM Fast Dimension Reduction Using Nir Ailon, Institute for Advanced Rademacher Series on Dual BCH Study; Edo Liberty, Yale 9:00 AM Codes University Estimators and Tail Bounds for Dimension Reduction in $l_\alpha$ $(0<\alpha\leq 2)$ Using Stable 9:25 AM Random Projections Ping Li, Cornell University Concurrent Sessions A Deterministic Sub-linear Time 1A 9:00 AM - 11:05 AM Sparse Fourier Algorithm via Non- adaptive Compressed Sensing M. A. Iwen, University of 9:50 AM Methods Michigan, Ann Arbor Explicit Constructions for Compressed Sensing of Sparse Piotr Indyk, Massachusetts 10:15 AM Signals Institute of Technology Aaron Bernstein and David Improved Distance Sensitivity Karger, Massachusetts Institute 10:40 AM Oracles Via Random Sampling of Technology S. Thomas McCormick, University Strongly Polynomial and Fully of British Columbia, Canada; Combinatorial Algorithms for Satoru Fujishige, Kyoto 9:00 AM Bisubmodular Function Minimization University, Japan Jin-Yi Cai, University of Holographic Algorithms With Wisconsin-Madison; Pinyan Lu, 9:25 AM Unsymmetric Signatures Tsinghua University, China Concurrent Sessions 1B 9:00 AM - 11:05 AM Guy Kindler, Weizmann Institute, Israel; Assaf Naor, Courant The UGC Hardness Threshold of the Institute; Gideon -

On Round-Efficient Argument Systems

On Round-Efficient Argument Systems Hoeteck Wee? Computer Science Division UC Berkeley Abstract. We consider the problem of constructing round-efficient public-coin argument systems, that is, interactive proof systems that are only computationally sound with a constant number of rounds. We focus on argument systems for NTime(T (n)) where either the communication complexity or the verifier’s running time is subpolynomial in T (n), such as Kilian’s argument system for NP [Kil92] and universal arguments [BG02,Mic00]. We begin with the observation that under standard complexity assumptions, such argument systems require at least 2 rounds. Next, we relate the existence of non-trivial 2-round argument systems to that of hard-on-average search problems in NP and that of efficient public-coin zero-knowledge arguments for NP. Finally, we show that the Fiat-Shamir paradigm [FS86] and Babai-Moran round reduction [BM88] fails to preserve computational soundness for some 3-round and 4-round argument systems. 1 Introduction 1.1 Background and Motivation Argument systems are like interactive proof systems, except we only require computational soundness, namely that it is computationally infeasible (and not impossible) for a prover to convince the verifier to accept inputs not in the language. The relaxation in the soundness requirement was used to obtain protocols for NP that are perfect zero-knowledge [BCC88], or constant-round with low communication complexity [Kil92], and in both cases, seems to also be necessary [For89,GH98]. In this paper, we focus on the study of round-efficient argument systems for NTime(T (n)) that do not necessarily satisfy any notion of secrecy, such as witness indistinguishability (WI), or zero-knowledge (although we do indulge in the occasional digression). -

Interactive Proofs of Proximity: Delegating Computation in Sublinear Time

Interactive proofs of proximity: Delegating computation in sublinear time The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Rothblum, Guy N., Salil Vadhan, and Avi Wigderson. 2013. “Interactive Proofs of Proximity: Delegating Computation in Sublinear Time.” Proceedings of the 45th Annual ACM Symposium on Symposium on Theory of Computing (STOC'13), Palo Alto, CA, June 01-04, 2013, ed. Dan Boneh, Tim Roughgarden, Joan Feigenbaum, 793-802. New York, NY: ACM Press. Published Version doi:10.1145/2488608.2488709 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:12561354 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Open Access Policy Articles, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#OAP Interactive Proofs of Proximity: Delegating Computation in Sublinear Time ∗ y Guy N. Rothblum Salil Vadhan Avi Wigderson Microsoft Research Harvard University Institute for Advanced Study [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT • Finally, we construct much better IPPs for specific We study interactive proofs with sublinear-time verifiers. functions, such as bipartiteness on random or well- These proof systems can be used to ensure approximate cor- mixing graphs, and the majority function. The query rectness for the results of computations delegated to an un- complexities of these protocols are provably better (by trusted server. Following the literature on property testing, exponential or polynomial factors) than what is possi- we seek proof systems where with high probability the ver- ble in the standard property testing model, i.e.