February 2010 Volume 1, Issue 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021-WATER-AND-SANITATION-SECTOR-Mtss MWRE

WATER AND SANITATION SECTOR 2021 – 2023 MEDIUM-TERM SECTOR STRATEGY (MTSS) STATE OF OSUN NOVEMBER, 2020 1 Foreword The State of Osun overall development objectives and planning tools are driven by the Vision 2020, Goal 6 of Sustainable Development Goals, Federal Republic of Nigeria Water Resources Master Plan, National Action Plan of Revitalization of the Nigerian’s WASH Sector 2018 with targets for water supply and Sanitation Sector aiming to reach 100% coverage rate by 2030. The Sector has prioritized water supply and sanitation services in the thematic themes as a critical service that will contribute significantly to attainment of the growth needed for the State during the next three years. It is from this perspective that WATSAN would like to ensure effective delivery of adequate, reliable, and sustainable services for water supply and sanitation for social and economic development. The present strategic plan for the water supply and sanitation sector is a revision of the previous one (approved in 2010) that had not been implemented for years. The revision of the WATSAN strategic plan was necessary to ensure that the sector strategy is aligned to the new objectives, targets, guidelines and State Development Plan for year 2019 to 2028. The existing resources provided by the State and development partners, including that for the previous years, only cater for the core basis of implementation of some strategic plan and budget for the programmes. But the financing gaps that still exist are expected to be bridged through the State budget allocation, mobilization from existing and future development partners working in the Water and Sanitation sector, long term loans acquired by the State for the big sector projects that will be implemented by Ministry of Water Resources and Energy. -

Pawnship Labour and Mediation in Colonial Osun Division of Southwestern Nigeria

Vol. 12(1), pp. 7-13, January-June 2020 DOI: 10.5897/AJHC2019.0458 Article Number: B7C98F963125 ISSN 2141-6672 Copyright ©2020 African Journal of History and Culture Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http://www.academicjournals.org/AJHC Review Pawnship labour and mediation in colonial Osun division of southwestern Nigeria Ajayi Abiodun Adeyemi College of Education, Ondo State, Nigeria. Received 9 November, 2019; Accepted 7 February, 2020 Pawnship was both a credit system and an important source of labour in Yoruba land. It was highly utilised in the first half of the twentieth century Osun Division, sequel to its easy adaptation to the colonial monetised economy. This study examined pawnship as a labour system that was deeply rooted in the Yoruba culture, and accounts for the reasons for its easy adaptability to the changes epitomized by the colonial economy itself with particular reference to Osun Division in Southwestern Nigeria. The restriction here is to focus on areas that were not adequately covered by the various existing literature on pawnship system in Yoruba land with a view to examining their peculiarities that distinguished them from the general norms that existed in the urban centres that were covered by earlier studies. The study adopted the historical approach which depends on oral data gathered through interviews, archival materials and relevant literature. It is hoped that the local peculiarities that the study intends to examine on pawnship here, will make a reasonable addition to the stock of the existing knowledge on Yoruba economic and social histories. Keywords: Pawnship, adaptability, Osun division, colonial economy, monetisation. -

Federal Republic of Nigeria - Official Gazette

Federal Republic of Nigeria - Official Gazette No. 47 Lagos ~ 29th September, 1977 Vol. 64 CONTENTS Page Page Movements of Officers ” ; 1444-55 “Asaba Inland Postal Agency—Opening of .. 1471 Loss of Local Purchase Orders oe .« 1471 Ministry of Defence—Nigerian Army— Commissions . 1455-61 Loss of Treasury Receipt Book ‘6 1471 Ministry of Defence—Nigerian Army— Loss of Cheque . 1471 Compulsory Retirement... 1462 Ministry of Education—Examination in Trade Dispute between Marine’ Drilling , Law, Civil Service Rules, Financial Regu- and Constructions Workers’ Union of lations, Police Orders and Instructions Nigeria and Zapata Marine Service and. Ppractical Palice Work-——December (Nigeria) Limited .e .. 1462. 1977 Series +. 1471-72 -Trade Dispute between Marine Drilling Oyo State of Nigeria Public Service and Construction Workers? Unions of Competition for Entry into the Admini- Nigeria and Transworld Drilling Com-- strative and Special Departmental Cadres pay (Nigeria) Limited . 1462-63 in 1978 , . 1472-73 Constituent Assembly—Elected Candi. Vacancies .- 1473-74 ; dates ~ -» ° 1463-69 Customs and Excise—Dieposal of Un- . Land required for the Service of the _ Claimed Goods at Koko Port o. 1474 Federal Military Government 1469-70 Termination of Oil Prospecting Licences 1470 InpEx To LecaL Notice in SupPLEMENT Royalty on Thorium and Zircon Ores . (1470 Provisional Royalty on Tantalite .. -- 1470 L.N. No. Short Title Page Provisional Royalty on Columbite 1470 53 Currency Offences Tribunal (Proce- Nkpat Enin Postal Agency--Opening of 1471 dure) (Amendment) Rules 1977... B241 1444 - OFFICIAL GAZETTE No. 47, Vol. 64 Government Notice No. 1235 NEW APPOINTMENTS AND OTHER STAFF CHANGES - The following are notified for general information _ NEW APPOINTMENTS Department ”Name ” Appointment- Date of Appointment Customs and Excise A j ~Clerical Assistant 1-2~73 ‘ ‘Adewoyin,f OfficerofCustoms and Excise 25-8-75 Akan: Cleri . -

Socio-Economic Impacts of Settlers in Ado-Ekiti

International Journal of History and Cultural Studies (IJHCS) Volume 3, Issue 2, 2017, PP 19-26 ISSN 2454-7646 (Print) & ISSN 2454-7654 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.20431/2454-7654.0302002 www.arcjournals.org Socio-Economic Impacts of Settlers in Ado-Ekiti Adeyinka Theresa Ajayi (PhD)1, Oyewale, Peter Oluwaseun2 Department of History and International Studies, Ekiti State University, Ado-Ekiti, Ekiti State Nigeria Abstract: Migration and trade are two important factors that led to the commercial growth and development of Ado-Ekiti during pre-colonial, colonial and post colonial period. These twin processes were facilitated by efforts of other ethnic groups, most notably the Ebira among others, and other Yoruba groups. Sadly there is a paucity of detailed historical studies on the settlement pattern of settlers in Ado-Ekiti. It is in a bid to fill this gap that this paper analyses the settlement pattern of settlers in Ado-Ekiti. The paper also highlights the socio- economic and political activities of settlers, especially their contributions to the development of Ado-Ekiti. Data for this study were collected via oral interviews and written sources. The study highlights the contributions of settlers in Ado-Ekiti to the overall development of the host community 1. INTRODUCTION Ado-Ekiti, the capital of Ekiti state is one of the state in southwest Nigeria. the state was carved out from Ondo state in 1996, since then, the state has witness a tremendous changes in her economic advancement. The state has witness the infix of people from different places. Settlement patterns in intergroup relations are assuming an important area of study in Nigeria historiography. -

Foreign Influence on Igbomina, C

FOREIGN INFLUENCE ON IGBOMINA, C. 1750-1900 By ABOYEJI, ADENIYI JUSTUS 97/15CA020 (B.A. (2001), M.A. (2006) HISTORY, UNILORIN) BEING A Ph.D THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF ILORIN, ILORIN, NIGERIA i FOREIGN INFLUENCE ON IGBOMINA, C. 1750-1900 By ABOYEJI, ADENIYI JUSTUS 97/15CA020 (B.A. (2001), M.A. (2006) HISTORY, UNILORIN) BEING A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL, UNIVERSITY OF ILORIN, ILORIN, IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF ILORIN, ILORIN, NIGERIA © March, 2015 ii iii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to the custodian of all Wisdom, Knowledge, Understanding, Might, Counsel, Reverential Fear (Isaiah 11:2) and the Donor of the ‘pen of the ready-writer’ (Psalms 45:1), through our Lord and Saviour, JESUS CHRIST. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My indebtedness for accomplishing this study is undoubtedly, enormous. Contributions within the academic circles, family link and notable individuals/personages deserve due acknowledgement. This is because a man who beats up his doctor after he has been cured is incapable of being grateful. Nature‘s cruelty, to candour, is more bearable than man‘s ingratitude to man. Words are undoubtedly inadequate to quantify the roles of my supervisors, Dr. Kolawole David Aiyedun and Professor Samuel Ovuete Aghalino, to whom special accolades are exclusively reserved. In spite of their busy schedules as Head of Department, Senior Professor and in many other capacities, they never denied me the benefits of their supervisory acumen. -

Violence in Nigeria : a Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis

Marc-Antoine Pérouse de Montclos (ed.) West African Politics and Society series 3 Violence in Nigeria Violence in Nigeria Violence in Nigeria Most of the academic literature on violence in Nigeria is qualitative. It rarely relies on quantitative data because police crime statistics are not reliable, or not available, or not even published. Moreover, the training of A qualitative and Nigerian social scientists often focuses on qualitative, cultural, and political issues. There is thus quantitative analysis a need to bridge the qualitative and quantitative approaches of conflict studies. This book represents an innovation and fills a gap in this regard. It is the first to introduce a discussion on such issues in a coherent manner, relying on a database that fills the lacunae in A qualitative and quantitative data from the security forces. The authors underline the necessity of a trend analysis to decipher the patterns and the complexity of violence in very different fields: from oil production to cattle breeding, radical Islam to motor accidents, land conflicts to witchcraft, and so on. In addition, analysis they argue for empirical investigation and a complementary approach using both qualitative and quantitative data. The book is therefore organized into two parts, with a focus first on statistical Marc-Antoine studies, then on fieldwork. Pérouse de Montclos (ed.) Marc-Antoine Pérouse de Montclos (ed.) 3 www.ascleiden.nl 3 African Studies Centre Violence in Nigeria: “A qualitative and quantitative analysis” 501890-L-bw-ASC 501890-L-bw-ASC African Studies Centre (ASC) Institut Français de Recherche en Afrique (IFRA) West African Politics and Society Series, Vol. -

Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC)

FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) OSUN STATE DIRECTORY OF POLLING UNITS Revised January 2015 DISCLAIMER The contents of this Directory should not be referred to as a legal or administrative document for the purpose of administrative boundary or political claims. Any error of omission or inclusion found should be brought to the attention of the Independent National Electoral Commission. INEC Nigeria Directory of Polling Units Revised January 2015 Page i Table of Contents Pages Disclaimer.............................................................................. i Table of Contents ………………………………………………. ii Foreword................................................................................ iv Acknowledgement.................................................................. v Summary of Polling Units....................................................... 1 LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREAS Atakumosa East…………………………………………… 2-6 Atakumosa West………………………………………….. 7-11 Ayedaade………………………………………………….. 12-17 Ayedire…………………………………………………….. 18-21 Boluwaduro………………………………………………… 22-26 Boripe………………………………………………………. 27-31 Ede North…………………………………………………... 32-37 Ede South………………………………………………….. 38-42 Egbedore…………………………………………………… 43-46 Ejigbo……………………………………………………….. 47-51 Ife Central………………………………........................... 52-58 Ifedayo……………………………………………………… 59-62 Ife East…………………………………………………….. 63-67 Ifelodun…………………………………………………….. 68-72 Ife North……………………………………………………. 73-77 Ife South……………………………………………………. 78-84 Ila……………………………………………………………. -

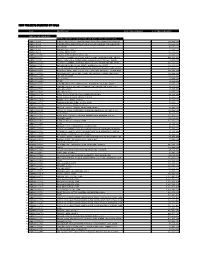

New Projects Inserted by Nass

NEW PROJECTS INSERTED BY NASS CODE MDA/PROJECT 2018 Proposed Budget 2018 Approved Budget FEDERAL MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE AND RURAL SUPPLYFEDERAL AND MINISTRY INSTALLATION OF AGRICULTURE OF LIGHT AND UP COMMUNITYRURAL DEVELOPMENT (ALL-IN- ONE) HQTRS SOLAR 1 ERGP4145301 STREET LIGHTS WITH LITHIUM BATTERY 3000/5000 LUMENS WITH PIR FOR 0 100,000,000 2 ERGP4145302 PROVISIONCONSTRUCTION OF SOLAR AND INSTALLATION POWERED BOREHOLES OF SOLAR IN BORHEOLEOYO EAST HOSPITALFOR KOGI STATEROAD, 0 100,000,000 3 ERGP4145303 OYOCONSTRUCTION STATE OF 1.3KM ROAD, TOYIN SURVEYO B/SHOP, GBONGUDU, AKOBO 0 50,000,000 4 ERGP4145304 IBADAN,CONSTRUCTION OYO STATE OF BAGUDU WAZIRI ROAD (1.5KM) AND EFU MADAMI ROAD 0 50,000,000 5 ERGP4145305 CONSTRUCTION(1.7KM), NIGER STATEAND PROVISION OF BOREHOLES IN IDEATO NORTH/SOUTH 0 100,000,000 6 ERGP445000690 SUPPLYFEDERAL AND CONSTITUENCY, INSTALLATION IMO OF STATE SOLAR STREET LIGHTS IN NNEWI SOUTH LGA 0 30,000,000 7 ERGP445000691 TOPROVISION THE FOLLOWING OF SOLAR LOCATIONS: STREET LIGHTS ODIKPI IN GARKUWARI,(100M), AMAKOM SABON (100M), GARIN OKOFIAKANURI 0 400,000,000 8 ERGP21500101 SUPPLYNGURU, YOBEAND INSTALLATION STATE (UNDER OF RURAL SOLAR ACCESS STREET MOBILITY LIGHTS INPROJECT NNEWI (RAMP)SOUTH LGA 0 30,000,000 9 ERGP445000692 TOSUPPLY THE FOLLOWINGAND INSTALLATION LOCATIONS: OF SOLAR AKABO STREET (100M), LIGHTS UHUEBE IN AKOWAVILLAGE, (100M) UTUH 0 500,000,000 10 ERGP445000693 ANDEROSION ARONDIZUOGU CONTROL IN(100M), AMOSO IDEATO - NCHARA NORTH ROAD, LGA, ETITI IMO EDDA, STATE AKIPO SOUTH LGA 0 200,000,000 11 ERGP445000694 -

Structure Plan for Ila-Orangun and Environs (2014 – 2033)

STRUCTURE PLAN FOR ILA-ORANGUN AND ENVIRONS (2014 – 2033) State of Osun Structure Plans Project NIGERIA SOKOTO i KATSINA BORNO JIGAWA Y OBE ZAMFARA Kano Maiduguri KANO KEBBI KADUNA BA UCHI Kaduna GOMBE NIGER ADAMAWA PLATEAU KWARA Abuja ABUJA CAPITAL TERRITORYNASSARAWA OYO T ARABA EKITI Oshogbo K OGI OSUN BENUE ONDO OGUN A ENUGU EDO N L LAGOS A a M g o B s R EBONY A ha nits CROSS O IMO DELTA ABIA RIVERS Aba RIVERS AKWA BAYELSA IBOM ii Orangun and Environs (2014 – 2033) - Structure Plan for Ila State of Osun Structure Plans Project STRUCTURE PLAN FOR ILA-ORANGUN AND ENVIRONS (2014 – 2033) State of Osun Structure Plans Project MINISTRY OF LANDS, PHYSICAL PLANNING AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT Copyright © United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT), 2014 All rights reserved United Nations Human Settlements Programme publications can be obtained from UN-HABITAT Regional and Information Offices or directly from: P.O. Box 30030, GPO 00100 Nairobi, Kenya. Fax: + (254 20) 762 4266/7 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.unhabitat.org HS Number: HS/092/11E ISBN Number (Volume): ………… Disclaimer The designation employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries, or regarding its economic system or degree of development. The analysis, conclusions and recommendations of the report do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN- HABITAT), the Governing Council of UN-HABITAT or its Member States. -

4. Kazeem Olojo: a Professional Painter and an Art Instructor Universal Studios of Art, Lagos, Nigeria

DOI: 10.1515/rae-2017-0032 Review of Artistic Education no. 14 2017 262-270 4. KAZEEM OLOJO: A PROFESSIONAL PAINTER AND AN ART INSTRUCTOR UNIVERSAL STUDIOS OF ART, LAGOS, NIGERIA Augustine Okola Bardi 107 Abstract: The works of art are priceless going by the quality of works exhibited by an artist. The artist tends to describe a particular scene near to the natural object in question. In the 15th and 16th centuries , France relayed on the impressionists who graduated from workshops and schools of apprentice in the likes of Gauguin, Monet, Manet, Degas, Renoir Cezanne, Delacroix and others to capture scenes of the Parisian country side that existed long age. The artist and his works remain indispensible to the existing societies. This form of art venture is not new to Nigeria where schools and workshops of apprenticeship exist. In Nigeria, the existing heritage and traditions if not for the artists will not be translated into art by the artists particularly painters like Dale, Oshinowo, Oguntokun, Emokpae, El-Dragg and others. The existence of workshops and schools of learning art have trained more artists to keep the aesthetical values of art. The society would be no doubt an unpleasant community without a touch of the arts. The artists who on daily bases create by painting, sculpting to make the environment a pleasurable place remain an important factor in the society, Key words: Workshops and Schools, Apprenticeship, Heritage and Traditions, Aesthetical values, Society 1. Introduction The importance of schools and workshops in Nigeria has helped to the development of art in the society for many years now. -

Les Chefferies Traditionnelles Au Nigeria NIGERIA

NIGERIA Etude 6 février 2015 Les chefferies traditionnelles au Nigeria Avertissement Ce document a été élaboré par la Division de l’Information, de la Documentation et des Recherches de l’Ofpra en vue de fournir des informations utiles à l’examen des demandes de protection internationale. Il ne prétend pas faire le traitement exhaustif de la problématique, ni apporter de preuves concluantes quant au fondement d’une demande de protection internationale particulière. Il ne doit pas être considéré comme une position officielle de l’Ofpra ou des autorités françaises. Ce document, rédigé conformément aux lignes directrices communes à l’Union européenne pour le traitement de l’information sur le pays d’origine (avril 2008) [cf. https://www.ofpra.gouv.fr/sites/default/files/atoms/files/lignes_directrices_europeennes.pdf], se veut impartial et se fonde principalement sur des renseignements puisés dans des sources qui sont à la disposition du public. Toutes les sources utilisées sont référencées. Elles ont été sélectionnées avec un souci constant de recouper les informations. Le fait qu’un événement, une personne ou une organisation déterminée ne soit pas mentionné(e) dans la présente production ne préjuge pas de son inexistence. La reproduction ou diffusion du document n’est pas autorisée, à l’exception d’un usage personnel, sauf accord de l’Ofpra en vertu de l’article L. 335-3 du code de la propriété intellectuelle. Les chefferies traditionnelles au Nigeria Table des matières Introduction 4 1. Bref rappel historique 5 2. Types et catégories de chefs traditionnels 5 2.1. Classifications 2.2. Titres traditionnels et titres honorifiques 2.3. -

Socio-Cultural Attitudes of Igbomina Tribe Toward Marriage and Abortion in Osun and Kwara States of Nigeria

International Journal of African Society, Cultures and Traditions Vol.5, No.1, pp.38-47, March 2017 Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.eajournals.org) SOCIO-CULTURAL ATTITUDES OF IGBOMINA TRIBE TOWARD MARRIAGE AND ABORTION IN OSUN AND KWARA STATES OF NIGERIA Dr. Adeleke Gbadebo Fatai (B.Sc. University of Ilorin, Ilorin-Nigeria); (LLB. Lead City University, Ibadan- Nigeria); M.Sc University of Ibadan, Ibadan-Nigeria; PhD. University of Ibadan- Nigeria) ABSTRACT: Abortion has been a social menace and its assessment depended on one's socio- legal views. Past scholars had concluded that abortion is either a felony or homicide; there is no known empirical study on socio-cultural implications of abortion to marriage in Igbomina tribe in Nigeria. Questionnaire was administered to 1036 respondents, 108 in-depth interviews were conducted and 156 Focus Group Discussions were held. Most (99.8%) respondents were not involved in abortion because 81.2% described induced abortion as a taboo. Majority (78.3%) respondents have seen more than forty women who died from miscarriage in traditional shrines and 59.7% passed through one-miscarriage or pregnancy complications but denied access to abortion. Any form of abortion resulted in marriage divorce, banned from eating natural foods, married outside the clan or total debarred from entry the land. The study found that only positive counseling, informational and educative services could bring about attitudinal change. KEYWORDS: Abortion, Socio-cultural, Attitude, Marriage, Igbomina tribe, INTRODUCTION Abortion may occur intentionally or naturally but the practice of intentional destruction of life or internal expulsion of an unborn child (abortion) seems to have become more popular and rampant among young girls nowadays.