Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lheidli T'enneh Perspectives on Resource Development

THE PARADOX OF DEVELOPMENT: LHEIDLI T'ENNEH PERSPECTIVES ON RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT by Geoffrey E.D. Hughes B.A., Northern Studies, University of Northern British Columbia, 2002 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN FIRST NATIONS STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN BRITISH COLUMBIA November 2011 © Geoffrey Hughes, 2011 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du 1+1 Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-87547-6 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-87547-6 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Capital and Labour in the Forest Economies of the Port Alberni and Prince George Districts, British Columbia, 1910-1939

ON THE FRIMGES: CAPITAL APJn LABOUR IN THE FOREST ECONOMIES OF THE PORT ALBERNI AND PRINCE GEORGE DISTRICTS, BRITISH COLUMBIA, 1910-1939 by Gordon Hugh Hak B.A. University of Victoria 1978 M.A. University of Guelph 1981 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF \I THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of History @ Gordon Hugh Hak 1986 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY April 1986 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name : GORDON HAK Degree : Ph.D. Title of thesis: On the Fringes: Capital and Labour in the Forest Economies of the Port Alberni and Prince George Districts, British Columbia, 1910-1939. Examining Committee: J. I[ Little, Chairman Allen ~ea@#, ~ekiorSupervisor - - Michael Fellman, Supervisory Committee Robin Fdr,Supervisory Commit tee Hugh ~&nst@: IJepa<tment of History Gerald Friesen, External Examiner Professor, History Department University of Manitoba PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis, project or extended essay (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this work for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. -

Ancestree Fall Edition 2018) Was Baptized in 18699 in New Westminster; He Would Have Been at Least Forty-Three Years Old When He Married

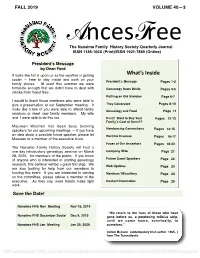

FALL 2019 VOLUME 40—3 !!!AncesTree! ! The Nanaimo Family History Society Quarterly Journal ISSN 1185-166X (Print)/ISSN 1921-7889 (Online) ! President’s Message by Dean Ford It looks like fall is upon us as the weather is getting What’s Inside cooler — time to stay inside and work on your President’s Message Pages 1-2 family stories. At least this summer we were fortunate enough that we didn’t have to deal with Genealogy News Briefs Pages 3-5 smoke from forest fires. Rattling an Old Skeleton Page 6-7 I would to thank those members who were able to give a presentation at our September meeting. It They Celebrated Pages 8-10 looks like a few of you were able to attend family Genealogy and Food Page 11 reunions or meet new family members. My wife and I were able to do this too. Psst!! Want to Buy Your Pages 12-13 Family’s Coat of Arms?? Maureen Wootten has been busy booking Membership Connections speakers for our upcoming meetings — if you have Pages 14-15 an idea about a possible future speaker, please let Wartime Evacuee Pages 16-17 Maureen or a member of the executive know. Faces of Our Ancestors Pages 18-20 The Nanaimo Family History Society will host a one day introductory genealogy seminar on March Company Wife Page 21 28, 2020, for members of the public. If you know of anyone who is interested in starting genealogy Future Guest Speakers Page 22 research, this seminar will be a great first step. We Web Updates Page 23 are also looking for help from our members in hosting this event. -

The Grand Trunk Pacific Railway and the Fort George Reserve, 1908-12

“You Don’t Suppose the Dominion Government Wants to Cheat the Indians?”:1 The Grand Trunk Pacific Railway and the Fort George Reserve, 1908-12 David Vogt and David Alexander Gamble n 1911, after a year of disjointed negotiations, the Grand Trunk Pacific gtp( ) Railway acquired the Lheidli T’enneh First Nation’s I500-hectare (1,366 acres )Fort George Reserve No. 1 at the confluence of the Fraser and Nechako rivers in present-day Prince George. The Lheidli T’enneh, then known to the Canadian government as the Fort George Indian Band, attempted several means to delay the surrender and raise the price of purchase. Ultimately, they agreed to surrender the reserve and move permanently to a second reserve, at Shelley, in exchange for $125,000. This was up from an initial offer of $68,300 and included $25,000 in construction funds and a pledge to preserve the village’s original cemetery (thereafter designated Reserve No. 1A). A specific history of the reserve surrender has not yet been published. Several historians have discussed the implications of the surrender in the context of the gtp’s relations with other “white … institutions,” in- cluding rival developers and the Roman Catholic Church, but they have generally given inadequate attention to the Lheidli T’enneh themselves. Intriguingly, and in contrast, the admittedly racist gtp-sponsored travel writer Frank Talbot alleged that responsibility for delays lay with the “cunning of the red man,” not with white institutions.2 1 Quotation from Royal Commission on Indian Affairs, “Meeting with the Fort George Tribe,” 22-23, Library and Archives Canada (hereafter lac), RG 10, file AH12, vol. -

Listing Brochure

Sutton Realty Ranchero Farms, 1505 Ranchero Drive, Prince George, BC 4 Titles / 1310 Acres $2,750,000 CAD (Right on the City Boundary ) The information contained herein is provided by the Seller and other sources believed to be reliable. Sutton Showplace Realty Harrison Hot Springs and its agents make no representation either verbal or otherwise as to the accuracy or correctness of the information contained herein and the buyer is cautioned to make any inquiries necessary to satisfy all questions or concerns. Freddy & Linda Marks facebook.com/suttonHarrisonHotSprings/ Unique Marketing for Unique Properties twitter.com/marks_linda Phone: 1 604 491 1060 linkedin.com/home?trk=hb_tab_home_top Fax: +1 604 491 1065 plus.google.com/102353941259187971458/posts Email: [email protected] Website: www.thebestdealsinbc.com Sutton Realty Ph: 1 604 491 1060 Freddy & Linda Marks [email protected] | www.thebestdealsinbc.com Ranchero Farms, 1505 Ranchero Drive, Prince George, BC Price: $2,750,000 CAD Type: Farm and Ranch Style: Commercial Garage: n/a Taxes: $3,060 CAD (2019) Development Level: Built Description Ranchero Farms is a true outdoorsman paradise, located at the edge of the Prince George city boundary. Encompassing 1310 Acres in 4 titles, the almost completely fenced ranch offers gorgeous views from several angles toward the northern metropolis of Prince George. Ranchero Farm is registered on one of the four titles. Operating as a working cattle & hay ranch, there is year-round access with well- built ranch infrastructure for cattle/caving, pigs and chickens. The operation easily supports 60 to 80 head with streams and water sources for pasturing cattle, even in very dry summers. -

Labor May Tie up Gtp Ladies of Si

g?--V1 % % ^PVV-%^-^ ^pftew. SOUTH FORT GEORGE, B. C, SATURDAY, OCTOBER 26, 1912. $3 PER ANNUM No news of the outcome of the libel trial at Kamloops this A. D. Campbell Succumbs to week has been received here and it is premature to place any LADIES OF SI. Heart Failure In Pool Room reliance in mere rumors that have been industriously circu lated about its termination, The same wild rumors were A. D. Campbell fell dead in the cast adrift when the trial first came up at Clinton last spring, Club pool room on Sunday morn when the news was flashed broad and wide that accused had ing. He had finished eating an WILL DEDRGANIZE LAND been placed in jail. Subsequent reports demonstrated the orange, and was jesting with POLICY OF HUHSON'S falsity of these early and unfounded rumors. Such reports others, when he he uttered a >,/: were to be expected, but the public should suspend judg laugh and fell out of his chair DAY CO. ment till the outcome is given in the columns of a reliable and collapsed. Medical assist Sir Thomas Skinner, the chairman of the board of governors of the Hud- . news-gatherer like the Herald and not in a "promoter's bul An event of unusual interest ance was summoned, but on arrival of Dr. Lazier the man son's Bay Co., arrived in Victoria last letin of facts." and the first of its kind in this week. In speaking of the anticipated section of Cariboo, is the propo was pronounced dead. The re changes of the old company in respect 3 sed entertainment and sale of mains were taken to the fire hall to their land policy, he said that and an inquest the following while it was true that in the past the The Peden Brothers Travel work the ladies of Stephen's Hudson's Bay Company had been accu church have arranged to take morning ascribed the cause to heart failure. -

Timeline of the Stellat'en and Aboriginal People's History In

Timeline of the Stellat’en and Aboriginal People’s History in Canada 1700s 1700s-2000s 1807: Simon Fraser wrote a letter detailing events he had witnessed in Stella. 1821: Peter Skene Ogden was made chief trader of the Hudson’s Bay Company. 1857: Gradual Civilization Act. 1800s 1880: Father Morice and Father Coccola came to the Fraser Lake and Fort St. James area. 1885: Arrival of Father A.G. Maurice. 1892: The Fraser Lake Indians are officially recognized, and a reserve is created. 1901: Provincial Government askes for a reduction of the number of reserves. 1906: Barricade Treaty. 1922-76: Lejac Residential School in operation. 1958-60: Stellaquo separates from Nadleh. 1900s 1976: Lejac Residential School closed. 1989: Stellaquo is recognized as 613 Ir. No 1 and Binta Lake as Ir. No 2. 1700s 1763 - British Royal Proclamation reserved undefined North American land for Aboriginal people. 1774 - Juan Perez Hernandez claimed the Northwestern coast of North America for Spain. 1791 - Spanish explorer Esteban Jose Martinez traded copper sheets to Nootka Sound Chief Maquinna for sawn timber. 1793 - Alexander Mackenzie became the first white man to travel through Carrier and Sekani territories while looking for fur-trading areas for the North West Company. 1800s 1805-1807 - Simon Fraser established four trading posts in Carrier and Sekani territories: Fort McLeod, Fort George, Fort St. James and Fort Fraser. Until the Hudson Bay Company and North West Company joined together in 1821, Fort St. James was the centre of government and commerce in British Columbia (then called New Caledonia). It claims to be the oldest established white settlement on the B.C. -

Public Art, Indoor Art Collection, Markers, Memorials and Other Items of Interest

City of Prince George’s public art, indoor art collection, markers, memorials and other items of interest Some of the public art in this inventory is part of the municipality’s collection however some of the work is privately owned but in the public realm. This is not an exhaustive list of the community’s public art. If you have any questions or comments, please contact us at 250 561-7646. Thank you to the City’s Public Art Advisory for all its work on developing and promoting art in the community 1 PRINCE GEORGE PUBLIC ART COLLECTION Artist: Gwen Boyle, Naomi Patterson, Gino Lenarduzzi Title: “Centennial Fountain” Location: Community Foundation Park 7th. Avenue and Dominion Street Description: Depicting Settler History to the Centennial. The Fountain section was removed in 2007 but the tile mosaic remains intact. Specifications Material: Concrete and Venetian Glass Tile Size: 8.5 m high Type of work: Glass Mosaic Installation Date: 1967 Project Initiative: City of Prince George Current Custodian: City of Prince George Artist : Nathan Scott Title: Terry Fox Location: Community Foundation Park 7th. Avenue and Dominion Street Description: On Sept 1, 1979 Terry Fox, his brother Darrel and friend Doug Alward, came to Prince George to participate In the Prince George to Boston Marathon (now known as the Labour Day Classic). Missing one limb due to cancer, Terry was determined to complete the marathon 17.5 mile course. At the following banquet, Terry revealed his hope to journey across the country raising awareness and funds In hopes of finding a cure for cancer. -

Language. Legemds, Amd Lore of the Carrier

SUBMITTED TO REV. H. POUPART. O.M.I., PH.D. in ii lusrgaccfc i n 11 gc—Majsmi ••• IIIIWHWII i ini DEAN OP THE FACULTY OF ARTS | LANGUAGE. LEGEMDS, AMD LORE OF THE , 1 : V CARRIER IKDIAHS ) By./ J-. B- . MUKRO\, M.S.A. Submitted as Thesis for the Ph.D. Degree, the University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada. UMI Number: DC53436 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI® UMI Microform DC53436 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 TABLE OF CONTENTS Pages Foreword Chapter 1 A Difficult Language .... 1-16 Chapter 2 Pilakamulahuh--The Aboriginal Lecturer 17 - 32 Chapter 3 Lore of the Pacific Coast . 33-44 Chapter 4 Dene Tribes and Waterways ... 45-61 Chapter 5 Carriers or Navigators .... 62-71 Chapter 6 Invention of Dene Syllabics . 72-88 Chapter 7 Some Legends of Na'kaztli ... 89 - 108 Chapter 8 Lakes and Landmarks .... 109 - 117 Chapter 9 Nautley Village and Legend of Estas 118 - 128 Chapter 10 Ancient Babine Epitaph ... -

I I Iii Ii I'

I I III Cl) II I’ 0 U d 0 I :: - .-. BRITISH COLUMBIA HISTORICAL QUARTERLY Published by the Archives of British Columbia in co-operation with the British Columbia Historical Association. EDITOR. W. KA LAMB. The University of British Columbia, Vancouver, B.C. ASSOCIATE EDITOR. WILLARD E. IRELAND. Provinial Archives, Victoria, B.C. (On active service, R.C.A.F.) ADVISORY BOARD. J. C. G00DFELL0w, Princeton. ROBIE L. REm, Vancouver. T. A. RICKARD, Victoria. W. N. SAGE, Vancouver. Editorial communications should be addressed to the Editor. Subscriptions should be sent to the Provincial Archives, Parliament Buildings, Victoria, B.C. Price, 50c. the copy, or $2 the year. Members of the British Columbia Historical Association in good standing receive the Quarterly without further charge. Neither the Provincial Archives nor the British Columbia Historical Association assumes any responsibility for statements made by contributors to the magazine. The Quarterly is indexed in Faxon’s Annual Magazine Subject-Index. BRITISH COLUMBIA HISTORICAL QUARTERLY “Any country worthy of a future should be interested in its past.” VOL. VIII. VICTORIA, B.C., OcToBER, 1944. No. 4 CONTENTS. PAGE. “Steamboat ‘Round the Bend “: American Steamers on the Fraser River in 1858. By Norman R. Hacking 255 Boom Days in Prince George: 1906—1913. ByF.E.Runnalls 281 The Journal of John Work, 1835. Being an account of his voyage northward from the Columbia River to Fort Simpson and return in the brig “Lamt,” January— October, 1835. Part III. Edited by Henry Drunimond Dee 307 Royal Commissions and Commissions of Inquiry in British. Columbia. A Checklist. Part II.: 1900—1910. -

1St Ave 167, 171, 194, 333, 356 357, 371 3Rd Ave. 90, 165, 182, 189, 216, 228, 241, 371 4Th Ave. 243 5Th Ave. 240 6Th Ave. 22 6

441441 IndexIndex 1st Ave 167, 171, 194, 333, 356 Aitchison (cont’d) Harold Keith 259; Americans, United States xx, 20, 34, 357, 371 Ida May 259; Irvin Thomas 39, 44, 63, 6566, 88, 108, 3rd Ave. 90, 165, 182, 189, 216, 259; James 252, 258260; 114, 127, 172, 188, 195197, 228, 241, 371 Joyce Juanita 259; Lorne (James) 209, 219, 225, 233234, 249, 4th Ave. 243 ii, 259260, 425; Mabel 254, 276, 286, 300, 318, 5th Ave. 240 (Lillian) 259; Mary Olive 259; 322, 327, 344, 347, 356, 6th Ave. 22 Olive 252, 258260; Ruth Lois 369, 380, 404, 420, 423; see 6 Mile, see Six Mile 259 also names of states (Alaska, 7th Ave. 241 Aitchison Road 258260 Arkansas, etc.). 8th Ave. 22, 87 Aizelwood, Wilfred and Mrs. 153 Amsterdam, S.S. (ship) 163 10th Ave. 22, 169 Alameda, Sask. 195 Andersen, Anna (Johnson) 45 11th Ave. 155 Alaska 11, 21, 266 Anderson farm 42; Alfred 99; Andy 14th Ave. 22 Alberta xix, 2, 4, 56, 64, 78, 80, 358, 368; Anne 68; Doris, see 15th Ave. 169, 171, 242 101, 114, 126, 128129, 139, Jarvis; Ernie 335; Ethel 153; 15 Mile Road 337 141, 150, 170, 181182, 186 Eugene 68; George 151, 153; 17th Ave. 22, 155 189, 195, 208, 229, 250251, Hans 128, 149, 152153; Jim 100 Mile House 114, 341 277, 287, 292, 306, 318, iii; Larry ii, 334, 434; Matt 297 Aase, Ilse iii, 262; Mons iii, 262 325, 331, 333, 344, 358359, 299; Ole 234236; Olive Abbott family 79 377378, 380, 394395, 412, (Clifford) 128, 152; Pete 276; Accidents, animal attack 10; 414; see also Calgary; Reinert 297; Shirley 153 automobile 38, 246, 264, 402; Edmonton; Jasper; Medicine Hat Anderson’s Lumber Yard 59, 228 avalanches 21; axe 100, 360; Albertville, Sask. -

Order in Council 810/1924

A 3 3 f"." Approved and ordered this 2. / - day of , A.D. 1924. antGovernor. i At the Executive Council Chamber, Victoria, PRESENT: The Honourable Mr. 11; •r in the Chair. Mr. rt Mr. ! (,. n Mr. Cf)fl 11 Mr. Mr. r Mr. Mr. To His Honour The Lieutenant-Governor in Council: The undersigned has the honour to .1;.a under t.'r . ,v i et; r, 2 'f ectlon ii of the Prnvinci_•,1 ,.1-(•' on; hqsr nitre on tAlf, , :„ )1 it, . 1 . 11,!lin the -lector .1 Li..-Itriet. In ....111.ph they recide reepeetively:- D this ( of J :'1•• . APP0OV::l. this d4y of ' 4 t'nti i:recuttvp Counell. ?s, 4 E NvINCI14 EILECTIOs CO:VISs. ina ALBERNI ELECTORAL DISTRICT, Browne, Harry Hughes Alberni Cox, Charles A. " Motion, James R. " Lynn, Albert A. " Paterson, John 1. w Johnson, Edward C. Pninbridge Markes, George W. of McKay, Mrs. Annie S. Brimfield Gilmore, Jrmer E. Cachelot Christensen, Chas. B. Crpe Scott Dawley, Clarence Clayoquot Bellamy, Augustus H. Kildonan Dane, Bernard T. San Joseph Bay P.O. l-ake Stafford, Henry I. Nootka Johnstone, James C. Port Alberni Roseborough, Sariuel G. " Wood, Alex. B. a Nordstrom, George Quatsino Shuttleworth, Henry Strnndby Cooper, John P. Tofino Kvarno, John H. Ucluelet Johnson, Richard T. " Blakemore, 'im. L. River Rd. Alberni Glassford, ,Thos.S. Alberni lotion, Jas. Gordon " Lade, John B. Port Alberni LcEackeen, Norman A. " Proctor, Melford L. " Hart, Bert Ira " Vaughan, Burton L. w Vaughan, Robert C. 1, Buttery, George rrington Braddock, Arthur D. " Crawford, David II Feary, Edward J.