Clark Memorandum: Spring 1999

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ezra Taft Benson

Religious Educator: Perspectives on the Restored Gospel Volume 9 Number 1 Article 12 4-1-2008 Profiles of the Prophets: Ezra Taft Benson John P. Livingstone [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/re BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Livingstone, John P. "Profiles of the Prophets: Ezra Taft Benson." Religious Educator: Perspectives on the Restored Gospel 9, no. 1 (2008). https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/re/vol9/iss1/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religious Educator: Perspectives on the Restored Gospel by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Profiles of the Prophets: Ezra Taft Benson John P. Livingstone John P. Livingstone ([email protected]) is an associate professor of Church history at Brigham Young University. The last few years of President Spencer W. Kimball’s life were fraught with poor health and diminished strength. When Ezra Taft Benson received the phone call announcing the death of the venerable old prophet, he was stricken with grief and reverence for the heavy task that now fell on him. On the Sunday following President Kimball’s death, November 10, 1985, the Quorum of the Twelve met in the Salt Lake Temple at three in the afternoon. During this most solemn of assemblies, Presi- dent Benson asked Gordon B. Hinckley and Thomas S. Mon- son to serve as his counselors. President Howard W. Hunter, next in seniority, set apart Ezra Taft Benson as President of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. -

Jugarenequipo-Partidos De Fernando Martin

www.jugarenequipo.es Hay 116 partidos en el informe Partidos de Fernando Martín Espina 25-marzo-1962 1979 1981 1986 1987 3-diciembre-1989 1981 1986 1987 1990 R.I.P. Nota: La casilla de verificación seleccionada indica los partidos completos Código colores sombreado duración indica fuente: Elinksbasket Grabación Intercambio Internet+edición Web RTVE Youtube 1981 Europeo 02/06/1981 Europeo 1981 Grupo Puestos 1º a 6º Partido 2 España 101-110 Unión de Repúblicas Socialistas Soviéticas 2002 Fernando Martín: 17 pts 3 reb 2 rec 1 tap. Chicho Sibilio: 25 pts 7 reb 5 fpr. Juan Antonio San Epifanio: 18 pts 6 reb 5 rec. Wayne Brabender: 2 pts 1 asi. Joaquín Costa: 6 asi 1 reb 1 pts. José María Margall: 6 pts 3 asi 1 reb. Manuel Flores: DNP. Fernando Romay: 9 pts 8 fpr 3 reb 1 tap. Juan Antonio Corbalán: 11 pts 4 asi. Rafael Rullán: DNP. Juan Domingo de la Cruz: 8 pts 4 reb 2 asi. Ignacio Solozábal: 5 asi 4 pts. Valdis Valters: 27 pts 8 asi 6 fpr. Anatoly Mychkine: 19 pts. Aleksandar Belostenny: 19 pts 8 reb 7 fpr 3 asi. Stanislav Eremine: 11 pts 12 asi 7 reb 4 rec. Guennady Kapustine: DNP. Serguei Tarakanov: 12 pts 2 reb. Alexandre Salnikov: 1'. Andrei Lopatov: 10 pts 6 reb 3 asi. Nikolai Derjugin: 8 pts 3 asi 2 reb. Vladimir Tkachenko: 4 pts 3 reb. Sergejus Jovaisa: 2 reb. Nikolai Fesenko: DNP. Muy buena PAL-MPG 4:3 720x576 5052 kb/s Variable AC3 2 canales 256 kb/s Televisión Española La 1 1:30:00 DVD5 03/06/1981 Europeo 1981 Grupo Puestos 1º a 6º Jornada 3 España 72-95 Yugoslavia 2784 Wayne Brabender: . -

Clark Memorandum: Spring 1999 J

Brigham Young University Law School BYU Law Digital Commons The lC ark Memorandum Law School Archives Spring 1999 Clark Memorandum: Spring 1999 J. Reuben Clark Law Society J. Reuben Clark Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/clarkmemorandum Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Courts Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, Legal Education Commons, Legal Ethics and Professional Responsibility Commons, and the Practical Theology Commons Recommended Citation J. Reuben Clark Law Society and J. Reuben Clark Law School, "Clark Memorandum: Spring 1999" (1999). The Clark Memorandum. 25. https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/clarkmemorandum/25 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Archives at BYU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The lC ark Memorandum by an authorized administrator of BYU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CM· Clark Memorandum J.Reuben Clark Law School Brigham Young University Spring | 1999 Weightier Matters · Cover Photograph John Snyder contents 40 Portraits 2 James Claflin 32 JohnW.Welch Weightier William K.Wallace III Matters The Challenge: Dallin H. Oaks Basing Your Career on Principles Elder Alexander B. Morrison 46 Memoranda BYU’s National Moot Court Champions H. Reese Hansen, Dean Scott W. Cameron, Editor Larry EchoHawk Joyce Janetski, Associate Editor CM Awards LoAnn Fieldsted, Assistant Editor David Eliason, Art Director 10 John Snyder, Photographer The Clark Memorandum The Constitutional is published by the J. Reuben Clark Law Society and the Thought of J. Reuben Clark Law School, J. Reuben Clark, Jr. -

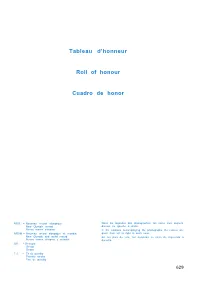

Tableau Dhonneur

Tableau d’honneur Roll of honour Cuadro de honor NRO = Nouveau record olympique Dans les legendes des photographes, les noms sont toujours New Olymplc record donnes de gauche a droite. Nueva marca olimpica. In the captions accompanying the photographs the names are NROM = Nouveau record olympique et mondial given from left to right in each case. New Olymplc and world record En los pies de foto, los nombres se citan de izquierda a Nueva marca olimpica y mundial. derecha. GR = Groupe Group Grupo. T. S. = Tir de penalty Penalty stroke Tiro de penalty 629 ● 5000 m 1. Said Aouita (MAR) (NRO) 13’05”59 Athlétisme 2. Markus Ryffel (SUI) 13’07”54 3. Antonio Leitao (POR) 13’09”20 Athletics 4. Tim Hutchings (GBR) 13’11”50 5. Paul Kipkoech (KEN) 13’14”40 Atletismo 6. Charles Cheruiyot (KEN) 13’18”41 ● 10 000 m 1. Alberto Cova (ITA) 27’47”54 2. Michael Mc Leod (GBR) 28’06”22 3. Mike Musyoki (KEN) 28’06”46 4. Salvatore Antibo (ITA) 28’06”50 1. Hommes - Men - Hombres 5 . Christoph Herle (FRG) 28’08”21 6. Sosthenes Bitok (KEN) 28’09”01 ● 100 m 1. Carl Lewis (USA) 9”99 ● 110 m haies, hurdles, vallas 2. Sam Graddy (USA) 10”19 1. Roger Kingdom (USA) (NRO) 13”20 3. Ben Johnson (CAN) 10”22 2. Greg Foster (USA) 13”23 4. Ron Brown (USA) 10”26 3. Arto Bryggare (FIN) 13”40 5. Michael Mc Farlane (GBR) 10”27 4. Mark McKoy (CAN) 13”45 6. Ray Stewart (JAM) 10”29 5. -

Results from the Games of the Xxiiird Olympic Games

Tableau d’honneur Roll of honour Cuadro de honor NRO = Nouveau record olympique Dans les légendes des photographies, les noms sont toujours New Olympic record donnés de gauche à droite. Nueva marca olimpica. In the captions accompanying the photographs the names are NROM = Nouveau record olympique et mondial given from left to right in each case. New Olympic and world record En los pies de foto, los nombres se citan de izquierda a Nueva marca olimpica y mundial derecha GR = Groupe Group Grupo. T.S. = Tir de penalty Penalty stroke Tiro de penalty. 629 • 5000 m 1. Said Aouita (MAR) (NRO) 13’05”59 Athlétisme 2. Markus Ryffel (SUI) 13'07"54 3. Antonio Leitao (POR) 13’09”20 Athletics 4. Tim Hutchings (GBR) 13’11”50 5. Paul Kipkoech (KEN) 13’14”40 Atletismo 6. Charles Cheruiyot (KEN) 13’18”41 • 10 000 m 1. Alberto Cova (ITA) 27’47”54 • 10 000 m 2. Michael MC Leod (GBR) 28’06”22 3. Mike Musyoki (KEN) 28’06”46 1. Alberto Cova (ITA) 27'47"54 2. 4. Salvatore Antibo (ITA) 28'06"50 Martti Vainio (FIN) 27'51"10 Michael MC Leod (GBR) 5. Christoph Herle (FRG) 28'08"21 3. 28'06"22 4. 6. Sosthenes Bitok (KEN) 28’09”01 Mike Musyoki (KEN) 28'06"46 5. Salvatore Antibo (ITA) 28'06"50 6. Christoph Herle (FRG) 28'08"21 • 100 m 1. Carl Lewis (USA) 9”99 • 110 m haies, hurdles, vallas 2. Sam Graddy (USA) 10”19 1. Roger Kingdom (USA) (NRO) 13”20 3. -

All-Canadian Teams / Équipes D'étoiles Canadiennes

ALL-CANADIAN TEAMS ÉQUIPES D'ÉTOILES / CANADIENNES The Selection Committee is Le comité de sélection est composé composed of members of the U de membres de l’Association des Sports Men’s Basketball Coaches entraîneurs de basketball masculin Association. de U Sports. 2016-17 First Team / Première équipe Connor Wood Carleton Conor Morgan UBC Adika Peter-McNeilly Ryerson Kevin Bercy StFX Thomas Cooper Calgary Second Team / Deuxième équipe Kaza Kajami-Keane Carleton Dele Ogundokun McGill Javon Masters UNB Caleb Agada Ottawa Shane Osayande Saskatchewan 2015-16 First Team / Première équipe Jacob Doerksen Ottawa Greg Surmacz Calgary Damian Buckley UNB Stuart Turnbull UQAM Christian Upshaw Brock Second Team / Deuxième équipe Aaron Best Ryerson Tyler Scott UPEI Kevon Parchment Fraser Valley Kaza Kajami-Keane Carleton Jordan Jensen-Whyte UBC 2014-15 First Team / Première équipe Johnny Berhanemeskel Ottawa Thomas Scrubb Carleton Chris McLaughlin Victoria Javon Masters UNB Philip Scrubb Carleton Second Team / Deuxième équipe Jarred Ogungbemi-Jackson Calgary Jahmal Jones Ryerson Tyler Scott UPEI Tommy Nixon UBC François Bourque McGill 2013-14 First Team / Première équipe Jordan Baker Alberta Terrell Evans Victoria Owen Klassen Acadia Lien Phillip Windsor Philip Scrubb Carleton Second Team / Deuxième équipe BASKETBALL – MEN - 1 Johnny Berhanemeskel Ottawa Vincent Dufort McGill Tyson Hinz Carleton Stephon Lamar Saskatchewan Javon Masters UNB 2012-13 First Team / Première équipe Philip Scrubb Carleton James Dorsey Cape Breton Stephon Lamar Saskatchewan -

Clark Memorandum: Spring 1990 J

Brigham Young University Law School BYU Law Digital Commons The lC ark Memorandum Law School Archives Spring 1990 Clark Memorandum: Spring 1990 J. Reuben Clark Law Society J. Reuben Clark Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/clarkmemorandum Part of the Legal Biography Commons, and the Legal Education Commons Recommended Citation J. Reuben Clark Law Society and J. Reuben Clark Law School, "Clark Memorandum: Spring 1990" (1990). The Clark Memorandum. 7. https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/clarkmemorandum/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Archives at BYU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The lC ark Memorandum by an authorized administrator of BYU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PISVISflHLNX XflO N I IIMEMORANDUM CONTENTS H ReeseDean Legal Olympians 2 Dean Kathy E. Pullins Claude E Zobell, Jr 12 Scott W Cameron Thoughts After Fifteen Years Editors Rex E. Lee Vincent S. Moreland Woody Deem 18 Associate Editor Colleague, Mentor, Friend 19 Charles D Cranney A Colleague Remembers Production1Copy Editor Edward L. Kimball A Student Remembers 22 Linda A. Sullivan Jim Parkinson Bruce Patrick Faculty Resolution 23 Designers John Snyder Memoranda 24 Photo Editor1Photographer Update JonathanSkousen Faculty Notes 36 TrPograPhY Class Notes 39 Spring 1990 The Clark Memorandum is published by the J Reuben Clark Society and the J Reuben Clark Law School, Brigham Young University Copyright 1990 by Brigham Young University All Rights Reserved 1 LE GA L O1YMPIAN S ... ................ .................................... KATHY D. &p INS , unfol! 9 1988 Summer. -

Clark Memorandum: Spring 1990

LE GA L O1YMPIAN S ... ................ .................................... KATHY D. &p INS , unfol! 9 1988 Summer. Olympics ts, and friends euben Clark Lazu School Tunmtte, me the Canadian basketball team, and He .... chaser on t . track and .field f .. sonal link between an x-- -4--- -- rmed a cluS":called Athletics they would subsidize my law 01 if I continued trair heir one stipulation was that I ross-country and track team I had was a law school there, so I enrolle in either sport. In one y n Law School. onary who was a walk-c Fkpbsidizcd my schooling while I continued to train chaser to a participant in the Olympic fi5.3 @#@&:~$my sccond year, I made the 1980 Olympic team. a second off the American record at 8:23 #$.S boycotted the games, I won the Olympic tri- &;jy American record during my second year in Was it about that time you stai-ted making defini: law school? I'd always planned on being an attorney-even whe s Wheit did your i. in grade school. My father was a Harvard law graduate. I ~ Aft :.:.:.> uiipcc he inqtilled that in me ..........5'...1 livinv in Eugene. si- ILLUSTRATION BY JOLEBN HUGHPS 2 Did you find that combining the daily in the top 10 in the world. That’s unpar- physical training and the rigors of study in alleled in track history. And that’s been law school were almost impossible at while I’ve been going through law school times? Or were the two endeavors more and working at a law firm. -

May 2007 New

THE MAY 2007 COVERCOVER STORY:STORY: GOINGGOING FORFOR THETHE GOALS,GOALS, P.P. 1818 AARONICAARONIC PRIESTHOOD:PRIESTHOOD: THETHE UNSEENUNSEEN POWER,POWER, P.P. 22 LEARNINGLEARNING FROM FROM YOURYOUR PATRIARCHALPATRIARCHAL BLESSING,BLESSING, P.P. 1414 WHYWHY II BELIEVEBELIEVE THETHE BOOKBOOK OFOF MORMON,MORMON, P.P. 2834 BEINGBEING AA BROTHER,BROTHER, P.P. 3030 The New Era Magazine ucceeding Volume 37, Number 5 May 2007 in a sport Official monthly publication takes for youth of S The Church of Jesus Christ determinationS to of Latter-day Saints keep on trying. The New Era can be found See “Play It Again, in the Gospel Library at www.lds.org. Sam,” p. 18. Editorial Offices: New Era 50 E. North Temple St. Rm. 2420 Salt Lake City, UT 84150-3220, USA E-mail Address: [email protected] To Submit Material: Please e-mail or send stories, articles, photos, poems, and ideas to the address above. For return, include a self-addressed, stamped envelope. To Subscribe: By phone: Call 1-800-537- 5971 to order using Visa, MasterCard, Discover Card, or American Express. Online: Go to www.ldscatalog.com. By mail: Send $8 U.S. check or money order to Distribution Services, P.O. Box 26368, Salt Lake City, UT 84126-0368, USA. To Change Address: Send old and new address information to Distribution Services at the address above. Please allow 60 days for changes to take effect. Cover: Samantha Southwick of Grand Blanc, Michigan, found her sport. See “Play It Again, Sam,” on p. 18. Cover photography: Janet Thomas (front) and Bob Stoner (back) Ponder, Pray, Perform, Persevere, p. -

Men's Basketball ALL-Canadian Teams ÉQUIPES D'étoiles Canadiennes DE Basketball Masculin

mEn'S BaSKETBaLL ALL-CanaDIan TEaMS ÉQUIPES D'ÉTOILES CanaDIEnnES DE BaSKETBaLL MASCULin The Selection Committee is composed of Le comité de sélection est composé de membres members of the U Sports Men’s Basketball de l’Association des entraîneurs de basketball Coaches Association. masculin de U SPORTS. 2019-20 First Team / Première équipe Brett Layton Calgary Kadre Gray Laurentian Keevan Veinot Dalhousie Calvin Epistola Ottawa Alix Lochard UQAM Second Team / Deuxième équipe Rashawn Browne Manitoba Tevaun Kokko Ryerson Jadon Cohee UBC Azaro Roker StFX Lloyd Pandi Carleton 2018-19 First Team / Première équipe Kadre Gray Laurentian Mambi Diawara Calgary Eddie Ekiyor Carleton Kemar Alleyne Saint Mary’s Brody Clarke Alberta Second Team / Deuxième équipe Jean-Victor Mukama Ryerson Ricardo Monge Concordia Jadon Cohee UBC Ali Sow Laurier Ibrahima Doumbouya UNB 2016-17 First Team / Première équipe Connor Wood Carleton Conor Morgan UBC Adika Peter-McNeilly Ryerson Kevin Bercy StFX Thomas Cooper Calgary Second Team / Deuxième équipe Kaza Kajami-Keane Carleton Dele Ogundokun McGill Javon Masters UNB Caleb Agada Ottawa Shane Osayande Saskatchewan 2015-16 First Team / Première équipe BASKETBALL – MEN - 1 mEn'S BaSKETBaLL ALL-CanaDIan TEaMS ÉQUIPES D'ÉTOILES CanaDIEnnES DE BaSKETBaLL MASCULin Jacob Doerksen Ottawa Greg Surmacz Calgary Damian Buckley UNB Stuart Turnbull UQAM Christian Upshaw Brock Second Team / Deuxième équipe Aaron Best Ryerson Tyler Scott UPEI Kevon Parchment Fraser Valley Kaza Kajami-Keane Carleton Jordan Jensen-Whyte UBC 2014-15