The Hockey Lockout of 2012–2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Injuries Continue to Plague Jets Seven Wounded Players Missed Saturday's Game

Winnipeg Free Press https://www.winnipegfreepress.com/sports/hockey/jets/injuries-continue-to-keep-jets-in-sick- bay-476497963.html?k=QAPMqC Injuries continue to plague Jets Seven wounded players missed Saturday's game By: Mike McIntyre WASHINGTON — Is there a doctor in the house? It’s been a common refrain for the Winnipeg Jets lately, as they just can’t seem to get close to a full, healthy lineup. Seven players were out due to injury in Saturday’s 2-1 loss in Philadelphia. Here’s what we know about all of them, with further updates expected today as the Jets return to action with a morning skate and then their game in Washington against the Capitals. Mark Scheifele has missed two games with a suspected shoulder injury, and there will be no rushing him back into action. He’s considered day-to-day at this point, and coach Paul Maurice had said last week he was a possibility to play either tonight, or tomorrow in Nashville. But don’t bet on it. Defenceman Toby Enstrom is battling a lower-body issue which kept him out for four games, saw him return in New Jersey last Thursday and then be back out on Saturday. Maurice said it’s a nagging thing that can change day-to-day, so his status is very much a question mark. Defenceman Dmitry Kulikov missed Saturday’s game after getting hurt Thursday in New Jersey. Maurice hasn’t said how long he could be out, only that it’s upper-body. Goalie Steve Mason has been sent back to Winnipeg for further testing on a lower-body injury he suffered late in the game against the New York Rangers last Tuesday, which was his first game back from his second concussion of the season. -

Pittsburgh Washington

PITTSBURGH VERSUS WASHINGTON FEBRUARY 14, 2021 | 3:00 PM ET | PPG PAINTS ARENA ANOTHER DAY, ANOTHER DOLLAR Over the course of their careers, Sidney Crosby and Evgeni Malkin have thrived in day games. They rank among the best in day games among active players, as well as in NHL history. PIT VERSUS Points Per Game in Day Games NHL History Highest Points Per Game in Day Games Among Active Players WSH 1. Mario Lemieux 1.55 Player GP Goals Assists Points PTS/GP 2. Cam Neely 1.44 Sidney Crosby 110 56 91 147 1.34 ‘20-21 OVERALL 3. Wayne Gretzky 1.41 Evgeni Malkin 112 61 81 142 1.27 6-5-1 RECORD 6-3-3 4. Pavel Bure 1.36 Alex Ovechkin 122 67 55 122 1.00 5. Sidney Crosby 1.34 Joe Thornton 150 39 107 146 0.97 6-3-1 LAST 10 GAMES 4-3-3 6. Evgeni Malkin 1.27 Claude Giroux 164 46 108 154 0.94 13.5% POWER-PLAY 37.0% n Malkin’s 61 goals in day games only trails Alex Ovechkin (67) for most among all active players, while Crosby’s 70.3% PENALTY KILL 81.4% 56 tallies is third-most. Crosby’s 91 assists are third-most among all active players in day games trailing Claude Giroux (108A in 164GP) and Joe Thornton (107A in 150GP). 2.83 GF/GP 3.58 SID THE KID VS. THE GR8 3.67 GA/GP 3.58 Sidney Crosby and Alex Ovechkin have met 54 times in the regular season ‘20-21 HEAD TO HEAD throughout their careers. -

NHL Playoffs PDF.Xlsx

Anaheim Ducks Boston Bruins POS PLAYER GP G A PTS +/- PIM POS PLAYER GP G A PTS +/- PIM F Ryan Getzlaf 74 15 58 73 7 49 F Brad Marchand 80 39 46 85 18 81 F Ryan Kesler 82 22 36 58 8 83 F David Pastrnak 75 34 36 70 11 34 F Corey Perry 82 19 34 53 2 76 F David Krejci 82 23 31 54 -12 26 F Rickard Rakell 71 33 18 51 10 12 F Patrice Bergeron 79 21 32 53 12 24 F Patrick Eaves~ 79 32 19 51 -2 24 D Torey Krug 81 8 43 51 -10 37 F Jakob Silfverberg 79 23 26 49 10 20 F Ryan Spooner 78 11 28 39 -8 14 D Cam Fowler 80 11 28 39 7 20 F David Backes 74 17 21 38 2 69 F Andrew Cogliano 82 16 19 35 11 26 D Zdeno Chara 75 10 19 29 18 59 F Antoine Vermette 72 9 19 28 -7 42 F Dominic Moore 82 11 14 25 2 44 F Nick Ritchie 77 14 14 28 4 62 F Drew Stafford~ 58 8 13 21 6 24 D Sami Vatanen 71 3 21 24 3 30 F Frank Vatrano 44 10 8 18 -3 14 D Hampus Lindholm 66 6 14 20 13 36 F Riley Nash 81 7 10 17 -1 14 D Josh Manson 82 5 12 17 14 82 D Brandon Carlo 82 6 10 16 9 59 F Ondrej Kase 53 5 10 15 -1 18 F Tim Schaller 59 7 7 14 -6 23 D Kevin Bieksa 81 3 11 14 0 63 F Austin Czarnik 49 5 8 13 -10 12 F Logan Shaw 55 3 7 10 3 10 D Kevan Miller 58 3 10 13 1 50 D Shea Theodore 34 2 7 9 -6 28 D Colin Miller 61 6 7 13 0 55 D Korbinian Holzer 32 2 5 7 0 23 D Adam McQuaid 77 2 8 10 4 71 F Chris Wagner 43 6 1 7 2 6 F Matt Beleskey 49 3 5 8 -10 47 D Brandon Montour 27 2 4 6 11 14 F Noel Acciari 29 2 3 5 3 16 D Clayton Stoner 14 1 2 3 0 28 D John-Michael Liles 36 0 5 5 1 4 F Ryan Garbutt 27 2 1 3 -3 20 F Jimmy Hayes 58 2 3 5 -3 29 F Jared Boll 51 0 3 3 -3 87 F Peter Cehlarik 11 0 2 2 -

Press Clips March 25, 2021

Buffalo Sabres Daily Press Clips March 25, 2021 Sabres’ winless streak hits 15 as Penguins roll to 5-2 win By Will Graves Associated Press March 25, 2021 PITTSBURGH (AP) — The Pittsburgh Penguins are tired. They’re hurting. And in a way, they’re scrambling. Nothing a visit from the reeling Buffalo Sabres can’t fix. Sidney Crosby picked up his 13th goal of the season, Tristan Jarry stopped 26 shots and the Penguins extended Buffalo’s winless streak to 15 games with a 5-2 victory on Wednesday night. Evan Rodrigues, Kris Letang, John Marino and Zach Aston-Reese scored also for the Penguins, who recovered from a sluggish three-game set against New Jersey in which they managed just one victory by pouncing on the undermanned and overmatched Sabres. “We’re a close group, a very resilient group,” Marino said. “We’ve had a lot of come-from-behind wins, a lot of bounce-back wins (like tonight). It says a lot about the guys in the room.” Buffalo goalie Dustin Tokarski, making his first NHL start in more than five years with Carter Hutton out due to a lower-body injury, finished with 37 saves and kept the Sabres in it until late in the second period, when Marino and Aston-Reese scored just over 2 minutes apart to give the Penguins all the cushion required. Rasmus Dahlin scored his second goal of the season and Victor Olofsson beat Jarry on a penalty shot in the third period, but the NHL’s worst team remained in a tailspin. -

The Effect of Geographic Location on Nhl Team Revenue

THE EFFECT OF GEOGRAPHIC LOCATION ON NHL TEAM REVENUE A THESIS Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Economics and Business The Colorado College In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts By J. Matthew Overman May/20l0 THE EFFECT OF GEOGRAPHIC LOCATION ON NHL TEAM REVENUE J. Matthew Overman May, 2010 Economics and Business Abstract This study attempts to explain the effect geographical location has on a National Hockey League (NHL) team's revenue. The effect location has will be compared to other determinants of revenue in the NHL. Data sets were collected from the 2006-2007 and the 2007-2008 seasons. Regression results were analyzed from these data sets. This study found that attendance, city population, and win percentage has a positive and significant effect on revenue. KEYWORDS: (Location, National Hockey League, Revenue,) ON MY HONOR, I HAVE NEITHER GIVEN NOR RECEIVED UNAUTHORIZED AID ON THIS THESIS Signature I would like to thank my thesis advisor Alexandra Anna for her guidance and patience throughout this process. I would also like to thank my parents for their full support of me from start to finish. None of this could have been possible without these people. TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT 111 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iv I. INTRODUCTION II. LITERATURE REVIEW 6 Location....................................................... .................................................. 7 Attendance..................................................................................... ................ 11 Star Players........ -

National Basketball Association

NATIONAL BASKETBALL ASSOCIATION {Appendix 2, to Sports Facility Reports, Volume 13} Research completed as of July 17, 2012 Team: Atlanta Hawks Principal Owner: Atlanta Spirit, LLC Year Established: 1949 as the Tri-City Blackhawks, moved to Milwaukee and shortened the name to become the Milwaukee Hawks in 1951, moved to St. Louis to become the St. Louis Hawks in 1955, moved to Atlanta to become the Atlanta Hawks in 1968. Team Website Most Recent Purchase Price ($/Mil): $250 (2004) included Atlanta Hawks, Atlanta Thrashers (NHL), and operating rights in Philips Arena. Current Value ($/Mil): $270 Percent Change From Last Year: -8% Arena: Philips Arena Date Built: 1999 Facility Cost ($/Mil): $213.5 Percentage of Arena Publicly Financed: 91% Facility Financing: The facility was financed through $130.75 million in government-backed bonds to be paid back at $12.5 million a year for 30 years. A 3% car rental tax was created to pay for $62 million of the public infrastructure costs and Time Warner contributed $20 million for the remaining infrastructure costs. Facility Website UPDATE: W/C Holdings put forth a bid on May 20, 2011 for $500 million to purchase the Atlanta Hawks, the Atlanta Thrashers (NHL), and ownership rights to Philips Arena. However, the Atlanta Spirit elected to sell the Thrashers to True North Sports Entertainment on May 31, 2011 for $170 million, including a $60 million in relocation fee, $20 million of which was kept by the Spirit. True North Sports Entertainment relocated the Thrashers to Winnipeg, Manitoba. As of July 2012, it does not appear that the move affected the Philips Arena naming rights deal, © Copyright 2012, National Sports Law Institute of Marquette University Law School Page 1 which stipulates Philips Electronics may walk away from the 20-year deal if either the Thrashers or the Hawks leave. -

Community Relations Programming in Non-Traditional NHL Markets

St. John Fisher College Fisher Digital Publications Sport Management Undergraduate Sport Management Department Fall 2013 Community Relations Programming in Non-Traditional NHL Markets Charles Ragusa St. John Fisher College Follow this and additional works at: https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/sport_undergrad Part of the Sports Management Commons How has open access to Fisher Digital Publications benefited ou?y Recommended Citation Ragusa, Charles, "Community Relations Programming in Non-Traditional NHL Markets" (2013). Sport Management Undergraduate. Paper 74. Please note that the Recommended Citation provides general citation information and may not be appropriate for your discipline. To receive help in creating a citation based on your discipline, please visit http://libguides.sjfc.edu/citations. This document is posted at https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/sport_undergrad/74 and is brought to you for free and open access by Fisher Digital Publications at St. John Fisher College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Community Relations Programming in Non-Traditional NHL Markets Abstract In the past twenty years, USA Hockey participation figures have grown at exponential rates, with overall amateur participation numbers reaching the half-million mark for the first time in 2011 (USA Hockey, 2012). Much of the overall growth of hockey in the United States has occurred in what some may define as non-traditional markets. These non-traditional markets comprise of Southern, mid-Atlantic, and West Coast cities, and several of the expansion and relocation teams that have grown since the early 1990s. In order to understand the growth of the sport, it is first important to look into what community outreach programs have been implemented by the various teams in the region, to help comprehend the varying sorts of awareness initiatives available to the public. -

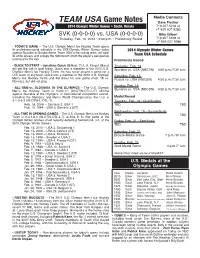

Team USA Game Notes Vs

Game Notes Media Contacts TEAM USA Dave Fischer 2014 Olympic Winter Games • Sochi, Russia 719.207.5216 or +7 925 007 9283 SVK (0-0-0-0) vs. USA (0-0-0-0) Mike Gilbert Thursday, Feb. 13, 2014 • 4:30 p.m. • Preliminary Round 719.207.5196 or +7 925 007 9286 • TODAY’S GAME -- The U.S. Olympic Men’s Ice Hockey Team opens its preliminary-round schedule in the XXII Olympic Winter Games today 2014 Olympic Winter Games against Slovakia at Shayba Arena. Team USA is the visiting team, will wear Team USA Schedule its white jerseys and occupy the right bench (from the player’s perspective looking onto the ice). Preliminary Round • QUICK TO START -- Jonathan Quick (Milford, Ct./L.A. Kings/UMass) Thursday, Feb. 13 will get the call in goal today. Quick was a member of the 2010 U.S. Slovakia vs. USA (NBCSN) 4:30 p.m./7:30 a.m. Olympic Men’s Ice Hockey Team. He has never played a game for a U.S. team at any level. Quick was a member of the 2010 U.S. Olympic Saturday, Feb. 15 Men’s Ice Hockey Team and did dress for one game (Feb. 18 vs. Russia vs. USA (NBCSN) 4:30 p.m./7:30 a.m. Norway), but did not play. Sunday, Feb. 16 • ALL-TIME vs. SLOVAKIA IN THE OLYMPICS -- The U.S. Olympic Men’s Ice Hockey Team is 0-0-0-1-1 (W-OTW-OTL-L-T) all-time Slovenia vs. USA (NBCSN) 4:30 p.m./7:30 a.m. -

The Amazing Rise and Fall of Bob Goodenow and the NHL Players Association (Revised and Updated), Key Porter Books, Toronto, 2006, Pp

Reviews 117 Bruce Dowbiggin, Money Players: The Amazing Rise and Fall of Bob Goodenow and the NHL Players Association (Revised and Updated), Key Porter Books, Toronto, 2006, pp. 310, pb, US$15.95. In 2003, Bruce Dowbiggin published Money Players: How Hockey’s Greatest Stars Beat the NHL at its Own Game (Macfarlane Walter and Ross, Toronto). It provided an historical account of major issues and developments in the National Hockey League (NHL). It predicted that there would be a major battle between owners and players in forthcoming negotiations over a new collective bargaining agreement. This prediction proved to be correct. The 2004-2005 season was disrupted by a 301 day lockout as the owners sought to impose a salary cap on players. It exceeded the previous longest dispute of 234 days which had occurred in Major League Baseball in 1994-95. Amongst other things, the lockout resulted in a cancellation of the Stanley Cup. This 2006 publication, as its subtitle suggests, provides information on the various events associated with the unfolding of this dispute and the subsequent capitulation of the National Hockey League Players’ Association (NHLPA) and the abandonment of its leader Bob Goodenow. The major strength of this book is that it provides a lively account of economic and industrial relations developments in hockey (or what Australians call ice hockey). Dowbiggin is a leading sporting journalist and commentator based in Calgary. His stock-in-trade is in reporting on interviews he has had with major protagonists in the hockey world. Money Players does not contain a bibliography. Historical information that he provides draws on the works of David Cruise and Alison Griffiths, Net Worth: Exploding the Myths of Pro Hockey (Viking, Toronto, 1991); Russ Conway, Game Misconduct: Alan Eagleson and the Corruption of Hockey (Macfarlane Walter and Ross, Toronto, 1995); and Gil Stein, Power Plays: An Inside Look at the Big Business of the National Hockey League (Birch Lane Press, Secaucus, NJ, 1997). -

Carl Gunnarsson Brief

2013 HOCKEY ARBITRATION COMPETITION OF CANADA Toronto Maple Leafs v Carl Gunnarsson Brief Submitted on Behalf of the Toronto Maple Leafs Team 31 Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………1 Overall Performance of the Player……………………………………………………………...1 Number of Games Played and Injury History…………………………………………………2 Length of Service in the NHL and with the Club……………………………………………...3 Overall Contribution to the Club……………………………………………………………….3 Special Qualities of Leadership or Public Appeal……………………………………………..4 Comparable Players……………………………………………………………………………..4 A) Anton Stralman………………………………………………………………………………5 B) Ryan Wilson…………………………………………………………………………………..6 Valuation & Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………7 Introduction This brief is in regards to the past performance of Mr. Carl Gunnarsson (the “Player”) of the Toronto Maple Leafs (the “Club”) for the matter of salary arbitration pursuant to Article 12.1(a) of the 2013 Collective Bargaining Agreement (the “CBA”) between the National Hockey League (the “NHL”) and the National Hockey League’s Players Association (the “NHLPA”). The CBA states seven categories of evidence that are admissible in salary arbitration cases in section 12.9(g)(ii): the overall performance of the player in previous seasons; the number of games played in previous seasons and any injuries or illnesses; the length of service of the player in the NHL and/or with the Club; the overall contribution of the player to the Club’s competitive success or failure; any special qualities of leadership or public appeal; the overall performance of any player(s) alleged to be comparable to the Player and the compensation of any players alleged to be comparable. As we will show in this brief, Mr. Gunnarsson, due to the above factors, should be compensated with a salary of $2,500,000. -

Weekly Champ List

Tied First Place Super Draft teams 1 BGRANT6 2235pts 2 REDLIGHRAIDERS6 2235pts Daniel Sedin (LW) VAN 104 Daniel Sedin (LW) VAN 104 Martin St. Louis (RW) TB 99 Martin St. Louis (RW) TB 99 Corey Perry (RW) ANA 98 Corey Perry (RW) ANA 98 Henrik Sedin (C) VAN 94 Henrik Sedin (C) VAN 94 Steven Stamkos (C) TB 91 Steven Stamkos (C) TB 91 Jarome Iginla (RW) CGY 86 Jarome Iginla (RW) CGY 86 Alex Ovechkin (LW) WAS 85 Alex Ovechkin (LW) WAS 85 Henrik Zetterberg (LW) DET 80 Henrik Zetterberg (LW) DET 80 Brad Richards (C) DAL 77 Brad Richards (C) DAL 77 Ryan Getzlaf (C) ANA 76 Ryan Getzlaf (C) ANA 76 Jonathan Toews (C) CHI 76 Jonathan Toews (C) CHI 76 Eric Staal (C) CAR 76 Eric Staal (C) CAR 76 Thomas Vanek (LW) BUF 73 Claude Giroux (RW) PHI 76 Patrick Marleau (LW) SJ 73 Patrick Marleau (LW) SJ 73 Patrick Kane (RW) CHI 73 Patrick Kane (RW) CHI 73 Loui Eriksson (RW) DAL 73 Loui Eriksson (RW) DAL 73 Anze Kopitar (C) LA 73 Anze Kopitar (C) LA 73 Bobby Ryan (LW) ANA 71 Joe Thornton (C) SJ 70 Joe Thornton (C) SJ 70 Danny Briere (RW) PHI 68 Sidney Crosby (C) PIT 66 John Tavares (C) NYI 67 Rick Nash (RW) CBJ 66 Sidney Crosby (C) PIT 66 Mike Richards (C) PHI 66 Mike Richards (C) PHI 66 Jeff Carter (RW) PHI 66 Nicklas Backstrom (C) WAS 65 Nicklas Backstrom (C) WAS 65 Phil Kessel (RW) TOR 64 Phil Kessel (RW) TOR 64 Dany Heatley (RW) SJ 64 Dany Heatley (RW) SJ 64 Mikko Koivu (C) MIN 62 Ilya Kovalchuk (RW) NJ 60 Ilya Kovalchuk (RW) NJ 60 Pavel Datsyuk (LW) DET 59 Pavel Datsyuk (LW) DET 59 Paul Stastny (C) COL 57 Paul Stastny (C) COL 57 Alexander Semin (RW) WAS -

Induction Spotlight Tsn/Rds Broadcast Zone Recent Acquisitions

HOCKEY HALL of FAME NEWS and EVENTS JOURNAL INDUCTION SPOTLIGHT TSN/RDS BROADCAST ZONE RECENT ACQUISITIONS SPRING 2015 CORPORATE MATTERS LETTER FROM THE INDUCTION 2015 • The annual elections meeting of the Selection Committee VICe-CHAIR will be held in Toronto on June 28 & 29, 2015 (with the announcement of the 2015 inductees on June 29th). Dear Teammates: • The Hockey Hall of Fame Induction Celebration will be held on Monday, November 9, 2015. Not long after another successful Graig Abel/HHOF Induction Celebration last November, the closely knit hockey community mourned the loss of two of ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING the game’s most accomplished and respected individuals in Pat • Scotty Bowman, David Branch, Brian Burke, Marc de Foy, Mike Gartner and Anders Quinn and Jean Beliveau. I have been privileged to get to know Hedberg were re-appointed each to a further term on the Selection Committee for the and work with these distinguished gentlemen throughout my 2015, 2016 and 2017 selection proceedings. life in hockey and like many others I was particularly heartened • The general voting Members ratified new By-law Nos. 25 and 26 which, among other by the outstanding tributes that spoke volumes to their impact amendments, provide for improved voting procedures applicable to all categories of on our great sport. Honoured Membership (visit HHOF.com for full transcripts). Although Chair of the Board for little more than a year, Pat left his mark on the Hockey Hall of Fame, overseeing the recruitment BOARD OF DIRECTORS Nominated by: of new members to the Selection Committee, initiating the Lanny McDonald, Chair (1) Corporate Governance Committee first comprehensive selection process review which led to Jim Gregory, Vice-Chair National Hockey League several by-law amendments, and establishing new and renewed Murray Costello Corporate Governance Committee partnerships.