Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vindicating Karma: Jazz and the Black Arts Movement

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2007 Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/ W. S. Tkweme University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Tkweme, W. S., "Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/" (2007). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 924. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/924 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Massachusetts Amherst Library Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/vindicatingkarmaOOtkwe This is an authorized facsimile, made from the microfilm master copy of the original dissertation or master thesis published by UMI. The bibliographic information for this thesis is contained in UMTs Dissertation Abstracts database, the only central source for accessing almost every doctoral dissertation accepted in North America since 1861. Dissertation UMI Services From:Pro£vuest COMPANY 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106-1346 USA 800.521.0600 734.761.4700 web www.il.proquest.com Printed in 2007 by digital xerographic process on acid-free paper V INDICATING KARMA: JAZZ AND THE BLACK ARTS MOVEMENT A Dissertation Presented by W.S. TKWEME Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 W.E.B. -

FRIDAY the 13TH: the MICROS PLAY MONK (Cuneiform Rune 310)

Bio information: THE MICROSCOPIC SEPTET Title: FRIDAY THE 13TH: THE MICROS PLAY MONK (Cuneiform Rune 310) Cuneiform promotion dept: (301) 589-8894 / fax (301) 589-1819 email: joyce [-at-] cuneiformrecords.com (Press & world radio); radio [-at-] cuneiformrecords.com (North American radio) http://www.cuneiformrecords.com FILE UNDER: JAZZ / THELONIOUS MONK / THE MICROSCOPIC SEPTET “If the Micros have a spiritual beacon, it’s Thelonious Monk. Like the maverick bebop pianist, they persevere... Their expanding core audience thrives on the group’s impeccable arrangements, terse, angular solos, and devil-may-care attitude. But Monk and the Micros have something else in common as well. Johnston tells a story: “Someone once walked up to Monk and said, “You know, Monk, people are laughing at your music.’ Monk replied, ‘Let ‘em laugh. People need to laugh a little more.” – Richard Gehr, Newsday, New York 1989 “There is immense power and careful logic in the music of Thelonious Sphere Monk. But you might have such a good time listening to it that you might not even notice. …His tunes… warmed the heart with their odd angles and bright colors. …he knew exactly how to make you feel good… The groove was paramount: When you’re swinging, swing some more,” he’d say...” – Vijay Iyer, “Ode to a Sphere,” JazzTimes, 2010 “When I replace Letterman… The band I'm considering…is the Microscopic Septet, a New York saxophone-quartet-plus-rhythm whose riffs do what riffs are supposed to do: set your pulse racing and lodge in your skull for days on end. … their humor is difficult to resist. -

Windward Passenger

MAY 2018—ISSUE 193 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM DAVE BURRELL WINDWARD PASSENGER PHEEROAN NICKI DOM HASAAN akLAFF PARROTT SALVADOR IBN ALI Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East MAY 2018—ISSUE 193 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 NEw York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : PHEEROAN aklaff 6 by anders griffen [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : nicki parrott 7 by jim motavalli General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The Cover : dave burrell 8 by john sharpe Advertising: [email protected] Encore : dom salvador by laurel gross Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest We Forget : HASAAN IBN ALI 10 by eric wendell [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : space time by ken dryden US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or VOXNEwS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] obituaries by andrey henkin Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Stuart Broomer, FESTIVAL REPORT Robert Bush, Thomas Conrad, 13 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, CD ReviewS 14 Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Mark Keresman, Marilyn Lester, Miscellany 43 Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Event Calendar 44 Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Contributing Writers Kevin Canfield, Marco Cangiano, Pierre Crépon George Grella, Laurel Gross, Jim Motavalli, Greg Packham, Eric Wendell Contributing Photographers In jazz parlance, the “rhythm section” is shorthand for piano, bass and drums. -

Chris Potter Circuits Quartet

03 Abr 2019 Erik Friedlander’s 21:00 Sala Suggia “Throw a glass” CICLO JAZZ Chris Potter Circuits Quartet Erik Friedlander’s “Throw a glass” Friedlander tomou contacto com a música muito cedo – cres‑ ceu numa casa cheia de música, começa a estudar guitarra com Erik Friedlander violoncelo apenas cinco anos e aos oito dedica ‑se ao violoncelo. Tocou e gravou Uri Caine piano com inúmeros artistas, incluindo The Mountain Goats, John Zorn, Mark Helias contrabaixo Dave Douglas e Courtney Love. O desejo de participar activamente Ches Smith bateria no turbilhão de estilos musicais que o cercava levou ‑o a encontrar novas formas de tocar violoncelo. Estas descobertas são as direc‑ Sob a inspiração das misteriosas esculturas de copos de absinto de trizes do seu trabalho como intérprete e compositor, com um catá‑ Picasso expostas no Museu de Arte Moderna (MoMA), Erik Fried- logo muito variado e original. lander e a sua banda The Throw criaram um álbum conceptual sobre a história sombria desta bebida e do seu uso como alucinogénio. Uri Caine nasceu em Filadélfia e começou a estudar piano com Friedlander formou o quarteto para uma actuação no The Stone Bernard Peiffer e composição com George Rochberg. Desde que em Nova Iorque e ficou logo “impressionado com a química que tive‑ se mudou para Nova Iorque, em 1985, gravou 33 álbuns como líder. mos”. Durante dois dias o grupo gravou Artemisia, um disco sobre Recentemente gravou Space Kiss (2017) com o Lutoslawski Quartet, aquela inspiração e a sua origem. “Muitas vezes estamos à procura Calibrated Thickness (2016) com o seu trio e Callithump (2015) com da grande revelação e a perder o milagre diário que está ali à vista de as suas composições para piano solo. -

Hermann NAEHRING: Wlodzimierz NAHORNY: NAIMA: Mari

This discography is automatically generated by The JazzOmat Database System written by Thomas Wagner For private use only! ------------------------------------------ Hermann NAEHRING: "Großstadtkinder" Hermann Naehring -perc,marimba,vib; Dietrich Petzold -v; Jens Naumilkat -c; Wolfgang Musick -b; Jannis Sotos -g,bouzouki; Stefan Dohanetz -d; Henry Osterloh -tymp; recorded 1985 in Berlin 24817 SCHLAGZEILEN 6.37 Amiga 856138 Hermann Naehring -perc,marimba,vib; Dietrich Petzold -v; Jens Naumilkat -c; Wolfgang Musick -b; Jannis Sotos -g,bouzouki; Stefan Dohanetz -d; recorded 1985 in Berlin 24818 SOUJA 7.02 --- Hermann Naehring -perc,marimba,vib; Dietrich Petzold -v; Jens Naumilkat -c; Wolfgang Musick -b; Jannis Sotos -g,bouzouki; Volker Schlott -fl; recorded 1985 in Berlin A) Orangenflip B) Pink-Punk Frosch ist krank C) Crash 24819 GROSSSTADTKINDER ((Orangenflip / Pink-Punk, Frosch ist krank / Crash)) 11.34 --- Hermann Naehring -perc,marimba,vib; Dietrich Petzold -v; Jens Naumilkat -c; Wolfgang Musick -b; Jannis Sotos -g,bouzouki; recorded 1985 in Berlin 24820 PHRYGIA 7.35 --- 24821 RIMBANA 4.05 --- 24822 CLIFFORD 2.53 --- ------------------------------------------ Wlodzimierz NAHORNY: "Heart" Wlodzimierz Nahorny -as,p; Jacek Ostaszewski -b; Sergiusz Perkowski -d; recorded November 1967 in Warsaw 34847 BALLAD OF TWO HEARTS 2.45 Muza XL-0452 34848 A MONTH OF GOODWILL 7.03 --- 34849 MUNIAK'S HEART 5.48 --- 34850 LEAKS 4.30 --- 34851 AT THE CASHIER 4.55 --- 34852 IT DEPENDS FOR WHOM 4.57 --- 34853 A PEDANT'S LETTER 5.00 --- 34854 ON A HIGH PEAK -

WBGO Expands Its Voice with Major New Digital Initiative

WBGO Expands Its Voice with Major New Digital Initiative Newark, January 10, 2017 – WBGO, the global leader in jazz radio, is pleased to announce a major advance in its online footprint and digital operations, in close partnership with NPR. Along with a recent update to its mobile app, the changes will involve a strong new online editorial focus and a redesigned website, launching on Jan. 17 with the support of NPR’s Digital Services. The upgraded WBGO.org will feature expanded content, including streaming on demand of all WBGO on-air programming for two weeks after air date, and a curated selection of exclusive WBGO archival content. The site will continue to be the home for widely acclaimed, nationally syndicated programs like The Checkout and Jazz Night in America, in video as well as podcast and streaming forms. And in a sign of WBGO’s commitment to quality, the organization has hired the world- renowned jazz journalist Nate Chinen to be Director of Editorial Content — a new role created in partnership with NPR. “We’re excited about having someone with Nate’s deep understanding of jazz, as well as his expert ability to communicate information about the music we love,” said WBGO President and CEO Amy Niles, who made the announcement last night at WBGO’s Board of Trustees meeting. “This is truly a transformative time in WBGO’s presentation of jazz as we launch our new digital platforms to complement our on air presence and bring new audiences to our music. Nate Chinen, truly a great editorial voice of our time, was the only choice to lead this new charge. -

Drums • Bobby Bradford - Trumpet • James Newton - Flute • David Murray - Tenor Sax • Roberto Miranda - Bass

1975 May 17 - Stanley Crouch Black Music Infinity Outdoors, afternoon, color snapshots. • Stanley Crouch - drums • Bobby Bradford - trumpet • James Newton - flute • David Murray - tenor sax • Roberto Miranda - bass June or July - John Carter Ensemble at Rudolph's Fine Arts Center (owner Rudolph Porter)Rudolph's Fine Art Center, 3320 West 50th Street (50th at Crenshaw) • John Carter — soprano sax & clarinet • Stanley Carter — bass • William Jeffrey — drums 1976 June 1 - John Fahey at The Lighthouse December 15 - WARNE MARSH PHOTO Shoot in his studio (a detached garage converted to a music studio) 1490 N. Mar Vista, Pasadena CA afternoon December 23 - Dexter Gordon at The Lighthouse 1976 June 21 – John Carter Ensemble at the Speakeasy, Santa Monica Blvd (just west of LaCienega) (first jazz photos with my new Fujica ST701 SLR camera) • John Carter — clarinet & soprano sax • Roberto Miranda — bass • Stanley Carter — bass • William Jeffrey — drums • Melba Joyce — vocals (Bobby Bradford's first wife) June 26 - Art Ensemble of Chicago Studio Z, on Slauson in South Central L.A. (in those days we called the area Watts) 2nd-floor artists studio. AEC + John Carter, clarinet sat in (I recorded this on cassette) Rassul Siddik, trumpet June 24 - AEC played 3 nights June 24-26 artist David Hammond's Studio Z shots of visitors (didn't play) Bobby Bradford, Tylon Barea (drummer, graphic artist), Rudolph Porter July 2 - Frank Lowe Quartet Century City Playhouse. • Frank Lowe — tenor sax • Butch Morris - drums; bass? • James Newton — cornet, violin; • Tylon Barea -- flute, sitting in (guest) July 7 - John Lee Hooker Calif State University Fullerton • w/Ron Thompson, guitar August 7 - James Newton Quartet w/guest John Carter Century City Playhouse September 5 - opening show at The Little Big Horn, 34 N. -

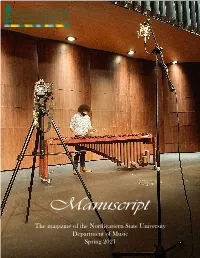

Manuscript Newsletter, Spring 2021 Edition

Manuscript The magazine of the Northeastern State University Department of Music Spring 2021 Contents 2 Welcome from the Chair Features 3 Guest Artists 5 NSU @ OkMEA 6 New Student Lounge & Opera Workshop 7 Green Country Jazz Festival 9 “Can’t stop the Music” (AKA NSU Music during a global pandemic) 11 Announcement of a new music degree 12 Student News 13 Alumni Feature 14 In Memorium 15 Faculty News 17 Endowments, Scholarships, & Donors Musicians: we are the most romantic of all artists. We believe in, and chase the illusive, intoxicating, unseen magic/beauty that exists in the universe. We are conduits for this magic/ beauty that has the ability to stir emotions that are fundamental to what it means to be human and alive. Here’s to us all....! - Dr. Ron Chioldi Welcome FROM THE CHAIR Spring 2021 marks the end of an academic year unlike any other. It was difficult. It was certainly stressful. So many modifications were made to our normal operating procedures due to the pandemic. Some of these modifications will inform how we operate in the future. Others, I hope we never have to implement ever again. Our faculty, staff, and students were resilient in the face of highly pressurized circum- stances. I want to thank them for their grace, adaptability, and understanding as things constantly changed. Early on in the pandemic, the performing arts were singled out as being particularly risky for infection. We took measures to ensure the safety of our faculty, staff, and students as best we could under state, local, and university protocols. -

Sarah Weaver Events Archive 2016

SARAH WEAVER EVENTS ARCHIVE 2016 12/20/16 SLM ENSEMBLE SOLO AND CHAMBER WORKS FOR PEACE – THE CELL THEATRE, NYC SLM Ensemble: Solo and Chamber Works for Peace December 20, 2016 8:00pm $20/$15 Students & Seniors Location: the cell 338 W. 23rd St, New York City Tickets: http://www.thecelltheatre.org/events/2016/12/20/slm-ensemble-solo-and-chamber- works-for-peace Musicians from the SLM Ensemble perform solo and chamber music compositions and improvisations for peace. Musicians: Jane Ira Bloom, soprano saxophone, Yoon Sun Choi, voice, Julie Ferrara, oboe, english horn, Joe McPhee, saxophone, trumpet, Zafer Tawil, oud, ney, Arab percussion, Dave Taylor, bass trombone, Min Xiao-Fen, pipa, Sarah Weaver, composer, computer The SLM Ensemble is a New York City based experimental music large ensemble created by co- artistic directors bassist/composer Mark Dresser and conductor/composer Sarah Weaver. The SLM Ensemble performs and records works for large ensemble, solo and chamber works, film/multimedia, and the telematic medium via the internet by Dresser, Weaver, and at times collaborating composers. The modular roster is composed of diverse pioneering musicians of our time. The name SLM is an acronym “Source Liminal Music” as well as a tri-consonantal root of words from several languages that mean “peace”. 11/29/16 REASONS OF RESONANCE: GERRY HEMINGWAY, SARAH WEAVER, BETH WARSHAFSKY – THE CELL THEATRE, NYC Reasons of Resonance Tuesday November 29, 2016 8:00PM $20/$15 Students & Seniors Location: the cell 338 W. 23rd Street, New York City Tickets: http://www.thecelltheatre.org/events/2016/11/29/reasons-of-resonance Solo performance by percussionist/composer Gerry Hemingway of collaborative works with composer Sarah Weaver and visual artist Beth Warshafsky. -

Stylistic Evolution of Jazz Drummer Ed Blackwell: the Cultural Intersection of New Orleans and West Africa

STYLISTIC EVOLUTION OF JAZZ DRUMMER ED BLACKWELL: THE CULTURAL INTERSECTION OF NEW ORLEANS AND WEST AFRICA David J. Schmalenberger Research Project submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Percussion/World Music Philip Faini, Chair Russell Dean, Ph.D. David Taddie, Ph.D. Christopher Wilkinson, Ph.D. Paschal Younge, Ed.D. Division of Music Morgantown, West Virginia 2000 Keywords: Jazz, Drumset, Blackwell, New Orleans Copyright 2000 David J. Schmalenberger ABSTRACT Stylistic Evolution of Jazz Drummer Ed Blackwell: The Cultural Intersection of New Orleans and West Africa David J. Schmalenberger The two primary functions of a jazz drummer are to maintain a consistent pulse and to support the soloists within the musical group. Throughout the twentieth century, jazz drummers have found creative ways to fulfill or challenge these roles. In the case of Bebop, for example, pioneers Kenny Clarke and Max Roach forged a new drumming style in the 1940’s that was markedly more independent technically, as well as more lyrical in both time-keeping and soloing. The stylistic innovations of Clarke and Roach also helped foster a new attitude: the acceptance of drummers as thoughtful, sensitive musical artists. These developments paved the way for the next generation of jazz drummers, one that would further challenge conventional musical roles in the post-Hard Bop era. One of Max Roach’s most faithful disciples was the New Orleans-born drummer Edward Joseph “Boogie” Blackwell (1929-1992). Ed Blackwell’s playing style at the beginning of his career in the late 1940’s was predominantly influenced by Bebop and the drumming vocabulary of Max Roach. -

Jason Robinson and Anthony Davis Dates Available in 2012-2014

Jason Robinson and Anthony Davis dates available in 2012-2014 “[For Robinson and Davis,] mood and interplay are more important than volume or scale.” -Ron Wynn, JazzTimes Magazine “[A] consummate summation of the jazz tradition in its most conversational and fundamental form.” -Troy Collins, All About Jazz “almost Ellingtonian in their lapidary elegance and beauty, highlighting the richness of Davis’ chordal voicings and Robinson’s big, brawny, Ben Webster-ish tone on tenor.” -The Stash Dauber “[I]nspired by their mutual passion for the music of Duke Ellington and spohisticated blues forms in a variety of hues, [their duet] is by turns lyrical and edgy, inviting and challenging. It’s steeped in jazz traditions that are handily extended, which is Robinson’s raison d’etre for making music.” -George Varge, San Diego Union-Tribune Moody, stark, and emotionally charged. Captured on their critically acclaimed debut recording Cerulean Landscape (Clean Feed, 2010), Robinson and pianist Anthony Davis have collaborated for more than ten years as a duo. Telepathic interplay, inspired improvisation, and dynamic original compositions carry listeners to a brilliant and evocative soundscape marked by emotional subtlety, a vast array of sounds, and poignant melodicism. With Duke Ellington, Billy Strayhorn, and the post- 60s jazz avant-garde as central reference points, Robinson and Davis bring together their formidable experience in many different music worlds, spilling over the traditional boundaries of the horn/piano duo. One moment minimalist, another orchestral, another beautifully melodic – their duo invites us into a sound world of deep blues, a place of surreal horizons, intense emotions, and hypnotic melodies. -

Too Many Notes: Complexity and Culture in Voyager����� Lewis, George E

Too Many Notes: Complexity and Culture in Voyager Lewis, George E. Leonardo Music Journal, Volume 10, 2000, pp. 33-39 (Article) Published by The MIT Press For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/lmj/summary/v010/10.1lewis.html Access Provided by University of California @ Santa Cruz at 09/27/11 9:42PM GMT W A Y S WAYS & MEANS & M E A Too Many Notes: Computers, N S Complexity and Culture in Voyager ABSTRACT The author discusses his computer music composition, Voyager, which employs a com- George E. Lewis puter-driven, interactive “virtual improvising orchestra” that ana- lyzes an improvisor’s performance in real time, generating both com- plex responses to the musician’s playing and independent behavior arising from the program’s own in- oyager [1,2] is a nonhierarchical, interactive mu- pears to stand practically alone in ternal processes. The author con- V the trenchancy and thoroughness tends that notions about the na- sical environment that privileges improvisation. In Voyager, improvisors engage in dialogue with a computer-driven, inter- of its analysis of these issues with ture and function of music are active “virtual improvising orchestra.” A computer program respect to computer music. This embedded in the structure of soft- ware-based music systems and analyzes aspects of a human improvisor’s performance in real viewpoint contrasts markedly that interactions with these sys- time, using that analysis to guide an automatic composition with Catherine M. Cameron’s [7] tems tend to reveal characteris- (or, if you will, improvisation) program that generates both rather celebratory ethnography- tics of the community of thought complex responses to the musician’s playing and indepen- at-a-distance of what she terms and culture that produced them.