Goju Ryu Kata Sanchin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Folk Dances of Shotokan by Rob Redmond

The Folk Dances of Shotokan by Rob Redmond Kevin Hawley 385 Ramsey Road Yardley, PA 19067 United States Copyright 2006 Rob Redmond. All Rights Reserved. No part of this may be reproduced for for any purpose, commercial or non-profit, without the express, written permission of the author. Listed with the US Library of Congress US Copyright Office Registration #TXu-1-167-868 Published by digital means by Rob Redmond PO BOX 41 Holly Springs, GA 30142 Second Edition, 2006 2 Kevin Hawley 385 Ramsey Road Yardley, PA 19067 United States In Gratitude The Karate Widow, my beautiful and apparently endlessly patient wife – Lorna. Thanks, Kevin Hawley, for saying, “You’re a writer, so write!” Thanks to the man who opened my eyes to Karate other than Shotokan – Rob Alvelais. Thanks to the wise man who named me 24 Fighting Chickens and listens to me complain – Gerald Bush. Thanks to my training buddy – Bob Greico. Thanks to John Cheetham, for publishing my articles in Shotokan Karate Magazine. Thanks to Mark Groenewold, for support, encouragement, and for taking the forums off my hands. And also thanks to the original Secret Order of the ^v^, without whom this content would never have been compiled: Roberto A. Alvelais, Gerald H. Bush IV, Malcolm Diamond, Lester Ingber, Shawn Jefferson, Peter C. Jensen, Jon Keeling, Michael Lamertz, Sorin Lemnariu, Scott Lippacher, Roshan Mamarvar, David Manise, Rolland Mueller, Chris Parsons, Elmar Schmeisser, Steven K. Shapiro, Bradley Webb, George Weller, and George Winter. And thanks to the fans of 24FC who’ve been reading my work all of these years and for some reason keep coming back. -

Kei Shin Kan Karate-Do Information Booklet KEI SHIN KAN KARATE - DO

Kei Shin Kan Karate-Do Information Booklet KEI SHIN KAN KARATE - DO Background and history Kei Shin Kan Karate-Do is a Japanese form of the martial art of Karate. It arrived in Australia in 1971 and has branches in Victoria, New South Wales, Queensland and Tasmania. The founder of Kei Shin Kan is Master Takazawa who was given a dojo by his teacher (Master Toyama) in 1958. Master Takazawa still lives in Nagano Japan. The head of Kei Shin Kan in Australia is Shihan Uchida in Sydney. The benefits of Karate There are many benefits from studying Karate, including : Learn self-defence and how to avoid dangerous situations Improve mental discipline and patience Improve strength, fitness and flexibility Meeting and socialising with a friendly group of students. It is likely to take many years for a normal person to achieve a high standard although students may progress faster depending on their dedication to training. While it is not realistic to set a particular time-frame to achieve black belt level, it is unusual to reach this level in less than 5 years. Again, the speed of progression varies with each individual. The syllabus Much emphasis is placed on learning proper basic techniques including stances, punches and blocks. These movements form the foundation of Karate practice. Sparring is introduced gradually starting with restricted sparring such as one-step sparring. As skills improve other sparring practice is introduced including three-action sparring, hands-only sparring and eventually free sparring. Safety in sparring is paramount. All sparring is strictly non-contact and protective equipment is worn also in case of accidental contact. -

SELF DEFENCE Syllabus

SELF DEFENCE Syllabus kyu 4-7yrs 7-15yrs Adult WHITE Self Defence 1 & 2 Self Defence 1 & 2 BLUE Self Defence 1 Self Defence 3 & 4 Self Defence 3 & 4 Knife Defence 1 ADV BLUE Self Defence 2 Self Defence 5 Self Defence 5 & 6 Knife Defence 1 YELLOW Self Defence 3 Self Defence 6 Self Defence 7 & 8 Knife Defence 2 ADV YELLOW Self Defence 4 Self Defence 7 & 8 Self Defence 9 & 10 Knife Defence 2 GREEN Self Defence 5 & 6 Self Defence 9 & 10 Extended SD 1-5 Knife Defence 3 ADV GREEN Self Defence 7 & 8 Extended SD 1-3 Extended SD 5-10 Knife Defence 3 Knife Defence 4 BROWN Self Defence 9 & 10 Extended SD 4-6 Knife Defence 5 Knife Defence 1 SD hook ADV BROWN Extended SD 1-3 Knife Defence 4 Extended SD all Striking Knife Defence 2 SD Kicks Attacks (kick / punch) Shodan Extended SD 7-10 SD Counter 1-10 + Grabs Knife Defence 5 Knife Defence 6 Nidan Knife Defence 6 Knife Defence 7 Self Defence P a g e | 1 ©Shiryodo Karate Contents SELF DEFENSE .......................................................................................................................................... 3 Self defence Combinations Overview ................................................................................................. 3 Self Defence 1 ................................................................................................................................. 5 Self Defence 2 ................................................................................................................................. 5 Self Defence 3 ................................................................................................................................ -

World Karate Federation

WORLD KARATE FEDERATION Version 6 Amended July 2009 VERSION 6 KOI A MENDED J ULY 2009 CONTENTS KUMITE RULES............................................................................................................................ 3 ARTICLE 1: KUMITE COMPETITION AREA............................................................................... 3 ARTICLE 2: OFFICIAL DRESS .................................................................................................... 4 ARTICLE 3: ORGANISATION OF KUMITE COMPETITIONS ...................................................... 6 ARTICLE 4: THE REFEREE PANEL ............................................................................................. 7 ARTICLE 5: DURATION OF BOUT ............................................................................................ 8 ARTICLE 6: SCORING ............................................................................................................... 8 ARTICLE 7: CRITERIA FOR DECISION..................................................................................... 12 ARTICLE 8: PROHIBITED BEHAVIOUR ................................................................................... 13 ARTICLE 9: PENALTIES........................................................................................................... 16 ARTICLE 10: INJURIES AND ACCIDENTS IN COMPETITION ................................................ 18 ARTICLE 11: OFFICIAL PROTEST ......................................................................................... 19 ARTICLE -

Black Belt History and Terminology STUDY GUIDE for Black Belt Testing

UECHIRYU BUTOKUKAITM Black Belt History and Terminology STUDY GUIDE For Black Belt Testing A Brief History of Uechiryu Karate-Do Uechiryu is purportedly based on three animals: The Tiger, Crane and Dragon The history of Uechiryu (Pronounced Way-Chee -Roo), began in Okinawa on May 5, 1877, with the birth of the founder: Kanbun Uechi. Kanbun was the oldest son of Samurai descendants Kantoku and Tsura Uechi. In 1897, Kanbun left Okinawa for China to avoid a Japanese Military conscription. He arrived in Fuchow City, Fukien Province and began his martial arts training. For the next ten years, he studied under the guidance of a Chinese Monk we know as Shushiwa. In 1907, Shushiwa encouraged Kanbun to open his own school. He eventually did in Nansoe, a day’s journey from Fuchow. Kanbun was credited with being the first Okinawan to operate a school in China. The school ran successfully for three years, then one of his students killed a neighbor in self-defense in a dispute over an irrigation matter. The incident hurt Kanbun to the point that he closed his school and returned to Okinawa. There he married, settled down as a farmer and vowed never to teach again. On June 26th, 1911, his first son Kanei Uechi was born. In 1924 Kanbun Uechi, along with many other Okinawans, left his home and went to Japan for stable employment. He arrived in Wakayama and worked as a janitor. It was here that he met a younger Okinawan Ryuyu Tomoyose. It was through this friendship that Kanbun agreed to begin teaching in a limited capacity. -

Sanchin Kata

Sanchin Kata It is an excellent kata for developing timing and rhythm. Kaishugata in contrast with Heishugata translates literally into 'open-hand kata'. Sanchin Kata. Sanchin kata test in Uechi-ryu - YouTube. While I am currently, at the time of this posting, only a 4th Kyu grade, and sanchin kata is generally emphasized at Dan-level grades, I find sanchin kata inspiring - its power, concentration, centeredness, and focus. Hands on hips. Don't forget the 4 speeds of Kata Training - Go Ho, Ju Ho, Seido Ho, and Go Ju Ho. Chishi Level 1 Workshop Instructional Video. Terauchi Sensei brought it on, he is a very inspirational instructor, I am amazed at his speed and control, his flexibility and his kime is owe inspiring. Step into right sanchin stance, perform kakushiken (crane beak strike – right hand come up over right ear to strike opponent on pressure point at junction of left side of opponents neck at collar bone, hand is at a 90° angle on wrist – use hip for power, then pull right hand back using an upside down u movement to have both hands at the ready, then bring back into left knee lift shin block then left foot lands in an left cat stance (10% weight on left foot 90% weight on back leg. For information on other Goju-Ryu Karate There are 12 official "core" katas for Goju-Ryu. Jul 8, 2015 - This Pin was discovered by Yhoiss Muñoz. Meaning of the Sanchin kata is “Three Battles”. Sanchin je izometrička kata gdje se svaki potez obavlja u stanju potpune napetosti, uz snažno, duboko disanje (ibuki) koji potječe iz donjeg dijela trbuha (tan den). -

Personal Development Student Guide

‘ 北剛柔空⼿道 Karate Studio of Utica Personal Development Student Guide UticaKarate.com Karate Studio of Utica Chief Instructor Profile Kyoshi Shihan Efren Reyes Has well over 30 years of experience practicing and teaching martial arts. He began his Karate training at age 19. No stranger to combative arts since he was already experienced in boxing at the time he was introduced to karate by his older brother. He has groomed and continues to mentor many of our blackbelts both near and far. He holds Kyoshi level certification in Goju-Ryu Karate under the late Sensei Urban and Sensei Van Cliff as well as a 3rd Dan in Aikijutsu under Sensei Van Cliff who has also ranked him master level in Chinese Goju-Ryu. Sensei Urban acknowledged Shihan has the mastery and expertise to be recognized as grand master of his own style of Goju-Ryu since he development of Goju-Ryu had evolved to point of growing his own vision and practice of karate unique to Shihan. This is what is practiced and taught at the Utica Karate. He has also studied Wing Chun in later years to further his understanding and perspective of techniques in close quarters. Shihan has promoted Karate-do through his style of Goju-Ryu under North American Goju karate. Shihan has directed many classes and seminars on various subjects’ ranging from basic self defense to meditation. Karate Studio of Utica Black Belt Instructor Profiles Sensei Philip Rosa Mr. Rosa holds the rank of Sensei (5th degree) and has been practicing Goju-Ryu Karate under Shihan Reyes since 1990. -

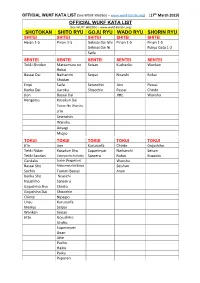

Official Wukf Kata List Shotokan Shito Ryu Goju

OFFICIAL WUKF KATA LIST (See WUKF WebSite – www.wukf-Karate.org) [17th March 2019] OFFICIAL WUKF KATA LIST (See WUKF WebSite – www.wukf-Karate.org) SHOTOKAN SHITO RYU GOJU RYU WADO RYU SHORIN RYU SHITEI SHITEI SHITEI SHITEI SHITEI Heian 1-5 Pinan 1-5 Gekisai Dai Ichi Pinan 1-5 Pinan 1-5 Gekisai Dai Ni Fukyu Gata 1-2 Saifa SENTEI SENTEI SENTEI SENTEI SENTEI Tekki Shodan Matsumura no Seisan Kushanku Wankan Rohai Bassai Dai Naihanchi Seipai Niseishi Rohai Shodan Empi Saifa Seiunchin Jion Passai Kanku Dai Jiuroku Shisochin Passai Chinto Jion Bassai Dai Jitte Wanshu Hangetsu Kosokun Dai Tomari No Wanshu Ji'in Seienchin Wanshu Aoyagi Miojio TOKUI TOKUI TOKUI TOKUI TOKUI Ji'in Jion Kururunfa Chinto Gojushiho Tekki Nidan Kosokun Sho Suparimpai Naihanchi Seisan Tekki Sandan Ciatanyara No Kushanku Sanseru Rohai Kusanku Gankaku Sochin (Aragaki ha) Wanshu Bassai Sho Matsumura No Bassai Seishan Sochin Tomari Bassai Anan Kanku Sho Niseichi Nijushiho Sanseiru Gojushiho Sho Chinto Gojushiho Dai Shisochin Chinte Nipaipo Unsu Kururunfa Meikyo Seipai Wankan Seisan Jitte Gojushiho Unshu Suparimpei Anan Jitte Pacho Haiku Paiku Papuren KATA LIST - WUKF COMPETITION UECHI RYU KYOKUSHINKAI BUDOKAN GOSOKU RYU SHITEI SHITEI SHITEI SHITEI Kanshiva Pinan 1-5 Heian 1-5 Kihon Ichi No Kata Sechin Kihon Yon No Kata Kanshu Kime Ni No Kata Seiryu (Kiyohide) Ryu No Kata Uke No Kata SENTEI SENTEI SENTEI SENTEI Sesan Geksai Dai Empi Ni No Kata Kanchin Tsuki No Kata Tekki 1-2 Kime No Kata Sanseryu Yantsu Bassai Dai Gosoku Tensho Kanku Dai Gosoku Yondan Saifa Jion Sanchin no -

2020 AAU Karate Handbook – General Rules

2020 AAU Karate Handbook – General Rules SECTION 1. AAU/USA KARATE RULES FOR COMPETITION ARTICLE 1. GENERAL GUIDELINE • The rules of competition for all tournaments, matches, and competitions licensed by AAU/USA KARATE shall be as stated herein. These rules shall be used in all licensed competitions, without modification or amendment for events which qualify athletes for further competition. • These rules are based upon the rules adopted by the different International Federations (IF) for competition. These rules, or any part thereof, may be modified or amended by AAU/USA KARATE National Executive Committee at any time. Whenever a specific rule is in conflict with a more general rule, the specific rule shall take precedence. • International Federation rules without modification shall be used in team selection procedure. Modifications without AAU/USA Karate Committee approval may not be made for any competition to select competitors for the AAU/USA National Karate Team. • Under special circumstances exceptions to these rules may be made with the prior approval of the National Executive Committee, with consultation with the Referee Council. • All exceptions to these rules, National competition or International Team selection, in whole or part must be approved by the AAU/USA Karate Executive Committee. ARTICLE 2. COMPETITION AREA • The competition area must be flat and devoid of hazard. The area shall be a matted square of suitable size. Where mats are not used, the competition area may be defined by marking the boundaries with colored tape of appropriate thickness. The area may be elevated to a height of up to one meter above floor level. -

Ueshiro Okinawan Karate Family Club (Est

Ueshiro Okinawan Karate Family Club (Est. 2004) Kyoshi Matt Kaplan, Denshi Shihan, Hachi-Dan Welcome to our Karate Family Club! To help you get started, below are our dojo guidelines and an introduction to Japanese terminology we often use in our classes. New white belts are invited to simply follow along and copy senior students to the best of your ability. Our Dojo Rules "Fundamental to Shorin-ryu is the observance by practitioners of courtesy and mutual respect." — Hanshi Robert Scaglione 1. Always show courtesy to all. 2. Address your instructor as sensei or sempai. 3. Bow to the instructor/sensei when entering or leaving the dojo. 4. When a black belt instructor of sandan rank or above enters or leaves the deck in gi (uniform) for the first time, the senior student stops the activity on the deck and calls the other students to attention. 5. Prohibited in the dojo: • No wearing jewelry or other ornaments on the deck during class • No food or drink allowed on the deck • No talking or laughing while class is in session • No profanity 6. Keep your gi clean. 7. Keep your fingernails and toenails short. 8. Refrain from misusing your karate knowledge. 9. Do not leave the deck while class is in session without the instructor’s permission. 10. Students should bow to each other before and after each practice. 11. Strive to promote the true spirit of the martial arts by: • Character - mental development • Health - physical development • Skill - proficiency in karate • Respect - courtesy to others • Humility - be aware of your shortcomings 12. -

Rank Requirements

KENSHO-KAI GOJU-RYU KARATE-DO RANK REQUIREMENTS 10 Kyu:(White Belt) Student joins association and purchases gi Requirements: Time to test, 3 months minimum attendance 75% . Must be current with dues 9 Kyu: (Yellow Belt) Kihon 1, Kihon 2 with no kicks, Kumite. Requirements: Time to test, 3 months minimum attendance 75% . Must be current with dues 8 Kyu: (Orange Belt) Kihon 1, Kihon 2, Kumite. Requirements: Time to test, 3 months minimum attendance 75% . Must be current with dues 7 Kyu: (Blue belt) Juji Ido 1, 2, Kumite. Requirements: Time to test, 3 months minimum attendance 75% . Must be current with dues 6 Kyu: (Green belt) Kihon 3, Kihon Ido 1,2 Taikyoku Jodan, Kumite. Requirements: Time to test, 3 months minimum attendance 75% . Must be current with dues 5 Kyu: (Green belt/purple stripe) Taikyoku Jodan, Chudan, Gedan, Kumite. Requirements: Time to test, 3 months minimum attendance 75% . Must be current with dues 4 Kyu: (Purple belt) Taikyoku Gedan, Sanchin, Gekkisai Shodan, Kumite. Requirements: Time to test, 3 months minimum attendance 75% . Must be current with dues 3 Kyu: (Purple belt/brown stripe) Taikyoku Gedan, Sanchin, Gekkisai Shodan, Kumite. Requirements: Time to test, 6 months minimum attendance 75% . Must be current with dues 2 Kyu: (Brown belt ) Sanchin, Gekkisai Shodan, Nidan, Kumite. Requirements: Time to test, 6 months minimum attendance 75% . Must be current with dues 1 Kyu: (Brown belt/black stripe ) Sanchin or Tensho, Gekkisai Shodan, Nidan, Unsu, Kumite. Requirements: Time to test, 6 months minimum attendance 75% . Must be current with dues Shodan: (Black belt ) Sanchin or Tensho, Unsu or Niseishi, Saifa, Kumite. -

The Shorin-Ryu Shorinkan of Williamsburg

Shorin-Ryu of Williamsburg The Shorin-Ryu Karate of Williamsburg Official Student Handbook Student Name: _________________________________________ Do not duplicate 1 Shorin-Ryu of Williamsburg General Information We are glad that you have chosen our school to begin your or your child’s journey in the martial arts. This handbook contains very important information regarding the guidelines and procedures of our school to better inform you of expectations and procedures regarding training. The quality of instruction and the training at our dojo are of the highest reputation and are designed to bring the best out of our students. We teach a code of personal and work ethics that produce citizens of strong physical ability but most importantly of high character. Students are expected to train with the utmost seriousness and always give their maximum physical effort when executing techniques in class. Instructors are always observing and evaluating our students based on their physical improvements but most of all, their development of respect, courtesy and discipline. Practicing karate is very similar to taking music lessons- there are no short cuts. As in music, there are people that possess natural ability and others that have to work harder to reach goals. There are no guarantees in music instruction that say someone will become a professional musician as in karate there are no guarantees that a student will achieve a certain belt. This will fall only on the student and whether they dedicate themselves to the instruction given to them. Our school does not offer quick paths to belts for a price as many commercial schools do.