Moral Sensibilities, Motivating Reasons, and Degrees of Moral Blame in Culpable Homicide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Winners & Finalists

2019 WINNERS & FINALISTS Associated Craft Award Winner Alison Watt The Radio Bureau Finalists MediaWorks Trade Marketing Team MediaWorks MediaWorks Radio Integration Team MediaWorks Best Community Campaign Winner Dena Roberts, Dominic Harvey, Tom McKenzie, Bex Dewhurst, Ryan Rathbone, Lucy 5 Marathons in 5 Days The Edge Network Carthew, Lucy Hills, Clinton Randell, Megan Annear, Ricky Bannister Finalists Leanne Hutchinson, Jason Gunn, Jay-Jay Feeney, Todd Fisher, Matt Anderson, Shae Jingle Bail More FM Network Osborne, Abby Quinn, Mel Low, Talia Purser Petition for Pride Mel Toomey, Casey Sullivan, Daniel Mac The Edge Wellington Best Content Best Content Director Winner Ryan Rathbone The Edge Network Finalists Ross Flahive ZM Network Christian Boston More FM Network Best Creative Feature Winner Whostalk ZB Phil Guyan, Josh Couch, Grace Bucknell, Phil Yule, Mike Hosking, Daryl Habraken Newstalk ZB Network / CBA Finalists Tarore John Cowan, Josh Couch, Rangi Kipa, Phil Yule Newstalk ZB Network / CBA Poo Towns of New Zealand Jeremy Pickford, Duncan Heyde, Thane Kirby, Jack Honeybone, Roisin Kelly The Rock Network Best Podcast Winner Gone Fishing Adam Dudding, Amy Maas, Tim Watkin, Justin Gregory, Rangi Powick, Jason Dorday RNZ National / Stuff Finalists Black Sheep William Ray, Tim Watkin RNZ National BANG! Melody Thomas, Tim Watkin RNZ National Best Show Producer - Music Show Winner Jeremy Pickford The Rock Drive with Thane & Dunc The Rock Network Finalists Alexandra Mullin The Edge Breakfast with Dom, Meg & Randell The Edge Network Ryan -

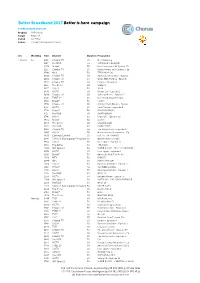

BB2017 Media Overview for Rsps

Better Broadband 2017 Better is here campaign TV PRE AIRDATE SPOTLIST Product All Products Target All 25-54 Period wc 7 May Source TVmap/The Nielsen Company w/c WeekDay Time Channel Duration Programme 7 May 17 Su 1112 Choice TV 30 No Advertising 7 May 17 Su 1217 the BOX 60 SURVIVOR: CAGAYAN 7 May 17 Su 1220 Bravo* 30 Real Housewives Of Sydney, Th 7 May 17 Su 1225 Choice TV 30 Better Homes and Gardens - Ep 7 May 17 Su 1340 MTV 30 TEEN MOM OG 7 May 17 Su 1410 Choice TV 30 American Restoration - Episod 7 May 17 Su 1454 Choice TV 60 Walks With My Dog - Episode 7 May 17 Su 1542 Choice TV 60 Empire - Episode 4 7 May 17 Su 1615 The Zone 60 SLIDERS 7 May 17 Su 1617 HGTV 30 16:00 7 May 17 Su 1640 HGTV 60 Hawaii Life - Episode 2 7 May 17 Su 1650 Choice TV 60 Jamie at Home - Episode 5 7 May 17 Su 1710 TVNZ 2* 60 Home and Away Omnibus 7 May 17 Su 1710 Bravo* 30 Catfish 7 May 17 Su 1710 Choice TV 30 Jimmy's Farm Diaries - Episod 7 May 17 Su 1717 HGTV 30 Yard Crashers - Episode 8 7 May 17 Su 1720 Prime* 30 RUGBY NATION 7 May 17 Su 1727 the BOX 30 SMACKDOWN 7 May 17 Su 1746 HGTV 60 Island Life - Episode 10 7 May 17 Su 1820 Bravo* 30 Catfish 7 May 17 Su 1854 The Zone 60 WIZARD WARS 7 May 17 Su 1905 the BOX 30 MAIN EVENT 7 May 17 Su 1906 Choice TV 60 The Living Room - Episode 37 7 May 17 Su 1906 HGTV 30 House Hunters Renovation - Ep 7 May 17 Su 1930 Comedy Central 30 LIVE AT THE APOLLO 7 May 17 Su 1945 Crime & Investigation Network 30 DEATH ROW STORIES 7 May 17 Su 1954 HGTV 30 Fixer Upper - Episode 6 7 May 17 Su 1955 The Zone 60 THE CAPE 7 May 17 Su 2000 -

Year in Review 2018/2019

Contents Shaping the Museum of the Future 2 Philanthropy on View 4 The Year at a Glance 8 Compelling Mix of Original and Touring Exhibitions 12 ROM Objects on Loan Locally and Globally 26 Leading-Edge Research 36 ROM Scholarship in Print 46 Community Connections 50 Access to First Peoples Art and Culture 58 Programming That Inspires 60 Learning at the ROM 66 Members and Volunteers 70 Digital Readiness 72 Philanthropy 74 ROM Leadership 80 Our Supporters 86 2 royal ontario museum year in review 2018–2019 3 One of the initiatives we were most proud of in 2018 was the opening of the Daphne Cockwell Gallery dedicated to First Peoples art & culture as free to the public every day the Museum is open. Initiatives such as this represent just one step on our journey. ROM programs and exhibitions continue to be bold, ambitious, and diverse, fostering discourse at home and around the world. Being Japanese Canadian: reflections on a broken world, Gods in My Home: Chinese New Year with Ancestor Portraits and Deity Prints and The Evidence Room helped ROM visitors connect past to present and understand forces and influences that have shaped our world, while #MeToo & the Arts brought forward a critical conversation about the arts, institutions, and cultural movements. Immersive and interactive exhibitions such as aptured in these pages is a pivotal Zuul: Life of an Armoured Dinosaur and Spiders: year for the Royal Ontario Museum. Fear & Fascination showcased groundbreaking Shaping Not only did the Museum’s robust ROM research and world-class storytelling. The Cattendance of 1.34 million visitors contribute to success achieved with these exhibitions set the our ranking as the #1 most-visited museum in stage for upcoming ROM-originals Bloodsuckers: the Canada and #7 in North America according to The Legends to Leeches, The Cloth That Changed the Art Newspaper, but a new report by Deloitte shows World: India’s Painted and Printed Cottons, and the the ROM, through its various activities, contributed busy slate of art, culture, and nature ahead. -

WHERE ARE the EXTRA ANALYSIS September 2020

WHERE ARE THE AUDIENCES? EXTRA ANALYSIS September 2020 Summary of the net daily reach of the main TV broadcasters on air and online in 2020 Daily reach 2020 – net reach of TV broadcasters. All New Zealanders 15+ • Net daily reach of TVNZ: 56% – Includes TVNZ 1, TVNZ 2, DUKE, TVNZ OnDemand • Net daily reach of Mediaworks : 25% – Includes Three, 3NOW • Net daily reach of SKY TV: 22% – Includes all SKY channels and SKY Ondemand Glasshouse Consulting June 20 2 The difference in the time each generation dedicate to different media each day is vast. 60+ year olds spend an average of nearly four hours watching TV and nearly 2½ hours listening to the radio each day. Conversely 15-39 year olds spend nearly 2½ hours watching SVOD, nearly two hours a day watching online video or listening to streamed music and nearly 1½ hours online gaming. Time spent consuming media 2020 – average minutes per day. Three generations of New Zealanders Q: Between (TIME PERIOD) about how long did you do (activity) for? 61 TV Total 143 229 110 Online Video 56 21 46 Radio 70 145 139 SVOD Total 99 32 120 Music Stream 46 12 84 Online Gaming 46 31 30 NZ On Demand 37 15-39s 26 15 40-59s Music 14 11 60+ year olds 10 Online NZ Radio 27 11 16 Note: in this chart average total minutes are based on a ll New Zealanders Podcast 6 and includes those who did not do each activity (i.e. zero minutes). 3 Media are ranked in order of daily reach among all New Zealanders. -

Booking-Guide-2015 Final.Pdf

04_Welcomes Unsound Adelaide 50_Lawrence English, Container, THEATRE 20_Azimut Vatican Shadow, Fushitsusha BOLD, INNOVATIVE FESTIVAL 26_riverrun 51_Atom™ and Robin Fox, Forest Swords, 28_Nufonia Must Fall The Bug, Shackleton SEEKS LIKE-MINDED FRIENDS 30_Black Diggers 51_Model 500, Mika Vainio, Evian Christ, 36_Beauty and the Beast Hieroglyphic Being 38_La Merda 52_Mogwai Become a Friend to receive: 40_The Cardinals 53_The Pop Group 15% discount 41_Dylan Thomas—Return Journey 54_Vampillia 42_Beckett Triptych 55_65daysofstatic Priority seating 43_SmallWaR 56_Soundpond.net Late Sessions And much more 44_Jack and the Beanstalk 57_The Experiment 58_Late Night in the Cathedral: Passio DANCE Cedar Lake Contemporary Ballet 59_Remember Tomorrow DISCOVER THE DETAILS 16_Mixed Rep 60_House of Dreams PAGE 70 OR VISIT ADELAIDEFESTIVAL.COM.AU 18_Orbo Novo 61_WOMADelaide VISUAL 06_Blinc ADELAIDE 62_Adelaide Writers’ Week ARTS 10_Bill Viola: Selected Works WRITERS’ 66_The Third Plate: Dan Barber 68_Trent Parke: The Black Rose WEEK 67_Kids’ Weekend MUSIC 14_Danny Elfman’s Music from the MORE 70_Bookings Films of Tim Burton 71_Schools 72_Access Gavin Bryars in Residence 73_Map 23_Marilyn Forever 74_Staff 24_Gavin Bryars Ensemble 75_Supporters and Philanthropy 24_Gavin Bryars Ensemble with guests 84_Corporate Hospitality 25_Jesus’ Blood Never Failed Me Yet and selected orchestral works FOLD OUT 84_Calendar 32_Fela! The Concert 34_Tommy 46_Blow the Bloody Doors Off!! Join us online 48_Abdullah Ibrahim 49_Richard Thompson Electric Trio #ADLFEST #ADLWW ADELAIDEFESTIVAL.COM.AU −03 Jay Weatherill Jack Snelling David Sefton PREMIER OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA MINISTER FOR THE ARTS ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Welcome to the 30th Adelaide Festival of Arts. The 2015 Adelaide Festival of Arts will please Greetings! It is my privilege and pleasure to In the performance program there is a huge range arts lovers everywhere with its broad program present to you the 2015 Adelaide Festival of Arts. -

Its All Happening Just When You Thought Things Were Winding Down

Its All Happening Just when you thought things were winding down for the year and there would be only holiday racing to concentrate on, a couple of recent important announcements have rather re-focussed the mind. First of all, and definitely most importantly, a successor to Edward Rennell has been announced. As I’ve said earlier, Edward leaves a massive pair for shoes to fill, and I know that, for years to come, his legacy will be felt in many different ways. My main concern about his replacement was that it would be someone who didn’t have the same passion and love for harness racing that he undoubtedly possessed. It was with relief then, that Peter Jensen was selected to take the reins, because he is yet another whose passion for our industry is without question. Having known Peter on both a personal and business basis for many years, he will bring skills and experience to the role that will be sorely needed in the difficult times ahead. Having attended a number of meetings he has had with the Trainers & Drivers Greater Canterbury Branch since he took over at Addington, it is clear that he made a favourable impression on some folk in our game who are not easily impressed, with his considered approach and willingness to at least listen to concerns, at the same time making no promises. The other announcement, this time from the Government, was the naming of those to be involved in the Ministerial Advisory Committee. Fearing that this body would be heavily slanted in favour of our sister code, it was pleasing to see that, with the obvious exception of Sir Peter Vela, that doesn’t appear to be the case. -

CERA Inquiry Final Report

CERA Inquiry Final Report CERA: Alleged Conflicts of Interest Inquiry for State Services Commissioner Final Report dated 31 March 2017 In accordance with Principle 7 of the Privacy Act 1993, a statement received from Mr Gallagher and Mr Nikoloff is attached at the end of the Report. Michael Heron QC Page 1 of 46 CERA Inquiry Final Report TABLE OF CONTENTS 1) Introduction 2) Summary of Conclusions 3) Applicable Standards 4) Discussion - PIML 5) Discussion - 32 Oxford Terrace – Mr Cleverley Appendix 1 – Terms of Reference Appendix 2 – Prime Minister’s letter and Jurisdiction Appendix 3 – Process and Documentation Appendix 4 – Applicable Standards Appendix 5 – Interviewees Appendix 6 – Canterbury DHB chronology Page 2 of 46 CERA Inquiry Final Report 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 The Canterbury Earthquake Recovery Authority (CERA) was established under the Canterbury Earthquake Recovery Act 2011 to assist with the Government's response to the devastating Canterbury earthquakes of 2010 and 2011. After five years of operation, CERA was disestablished on 18 April 2016. 1.2 Within CERA, the Implementation/Central City Development Unit (CCDU) set out to drive the rebuild of central Christchurch. The Investment Strategy group sat within that unit and was responsible for retaining, promoting and attracting investment in Christchurch. 1.3 In early 2017, investigative journalist Martin van Beynen published a series of articles on alleged conflicts of interest within CERA and CCDU. Due to the serious allegations raised, the State Services Commissioner appointed me to undertake this Inquiry on his behalf on 7 February 2017 pursuant to sections 23(1) and 25(2) of the State Sector Act 1988. -

Fairfax/NZME – Response to Questions Arising from the Conference

1 PUBLIC VERSION NZME AND FAIRFAX RESPONSE TO COMMERCE COMMISSION QUESTIONS ARISING FROM THE CONFERENCE ON 6 AND 7 DECEMBER 2016 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. During its recent Conference held on 6 and 7 December 2016, the Commissioners asked the parties to follow up on a number of points. This paper sets out the parties' responses on those questions, and also provides answers to some further follow-up questions that the parties have received since the Conference. 2. The main points that this response covers are as follows: (a) Inefficient duplication of commodity news (external plurality): The Commissioners asked the parties to produce examples of "commodity" news coverage as between the five main media organisations being similar ("digger hits bridge" was provided as an example of where all the major media organisations covered effectively the same point). Reducing that duplication will be efficiency enhancing and will not materially detract from the volume or quality of news coverage. (b) A wide variety of perspectives are covered within each publication (internal plurality): The editors provided the Commission with examples of how each publication covers a wide variety of perspectives, as that is what attracts the greatest audience. This is true both within and across each of the parties' publications. The Commission asked for examples, which are provided in this response, together with additional material about why those incentives do not change post-Merger. (c) Constitutional safeguards on editorial independence: The Commissioners asked about what existing structures protected editorial independence and balance and fairness in reporting. This was asked both in the context of a possible future sale of Fairfax's stake, and in the context of the protections available to those subject to negative reporting seeking fairness and balance. -

The Criminal Justice Response to Women Who Kill an Interview with Helena Kennedy Sheila Quaid and Catherine Itzin Introduction

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sunderland University Institutional Repository The criminal justice response to women who kill An interview with Helena Kennedy Sheila Quaid and Catherine Itzin Introduction This chapter is based on an interview with Helena Kennedy QC by Catherine Itzin. It has been edited into the form of a narrative, covering a range of issues relating to women and the criminal justice system, and in particular explores the question of 'Why do women kill?'. In Helena Kennedy's experience of defending women, she asserts that most women kill in desperation, in self... defence or in the defence of their children. Women's experience of violence and escape from violence has received much critical comment and campaigning for law reform over the past few years and some cases such as Sara Thornton, Kiranjit Ahluwalia and Emma Humphreys have achieved a high public profile as campaigners have fought for their release from life sentences. All three women had sustained years of violence and abuse from their partners and had killed in their attempts to stop the violence. Who women kill Women are rarely involved in serial killing and they almost never go out and plan the anonymous killing of a victim with whom who they have no connection at all. For the most part women kill people they know and primarily these people are men. They kill within the domestic arena: they kill their husbands, their lovers, their boyfriends and sometimes they kill their children. Occasion... ally it might stretch beyond the domestic parameter, but the numbers are incredibly small, and when women kill it is when something is going very wrong with their domestic environment. -

What Is Penal Populism?

The Power of Penal Populism: Public Influences on Penal and Sentencing Policy from 1999 to 2008 By Tess Bartlett A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Criminology View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ResearchArchive at Victoria University of Wellington School of Social and Cultural Studies Victoria University of Wellington June 2009 Abstract This thesis explains the rise and power of penal populism in contemporary New Zealand society. It argues that the rise of penal populism can be attributed to social, economic and political changes that have taken place in New Zealand since the postwar years. These changes undermined the prevailing penalwelfare logic that had dominated policymaking in this area since 1945. It examines the way in which ‘the public’ became more involved in the administration of penal policy from 1999 to 2008. The credibility given to a law and order referendum in 1999, which drew attention to crime victims and ‘tough on crime’ discourse, exemplified their new role. In its aftermath, greater influence was given to the public and groups speaking on its behalf. The referendum also influenced political discourse in New Zealand, with politicians increasingly using ‘tough on crime’ policies in election campaigns as it was believed that this was what ‘the public’ wanted when it came to criminal justice issues. As part of these developments, the thesis examines the rise of the Sensible Sentencing Trust, a unique law and order pressure group that advocates for victims’ rights and the harsh treatment of offenders. -

Everfarm® − Climate Adapted Perennial-Based Farming Systems

® Everfarm − Climate adapted perennial-based farming systems for dryland agriculture in southern Australia Final Report Robert Farquharson, Amir Abadi, John Finlayson, Thiagarajah Ramilan, De Li Lui, Muhuddin Anwar, Steve Clark, Susan Robertson, Daniel Mendham, Quenten Thomas and John McGrath EverFarm® – Climate adapted perennial-based farming systems for dryland agriculture in southern Australia Robert Farquharson1, Amir Abadi 2, John Finlayson3, Thiagarajah Ramilan1, De Li Liu4, Muhuddin R Anwar 4, Steve Clark5, Susan Robertson6, Daniel Mendham7, Quenten Thomas8 and John McGrath9 1 Future Farm Industries Cooperative Research Centre and University of Melbourne 2 Future Farm Industries Cooperative Research Centre and Western Australian Department of Environment and Conservation 3 Future Farm Industries Cooperative Research Centre and University of Western Australia 4 New South Wales Department of Primary Industries 5 Victorian Department of Primary Industries 6 Charles Sturt University 7 Future Farm Industries Cooperative Research Centre and CSIRO Ecosystem Sciences 8 Quisitive Pty Ltd 9 Future Farm Industries Cooperative Research Centre May 2013 A project report funded by the National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility and the Future Farm Industries Cooperative Research Centre Published by the National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility ISBN: 978-1-925039-66-5 NCCARF Publication 95/13 © 2013 Future Farm Industries Cooperative Research Centre This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the copyright holder. Please cite this report as: Farquharson, R, Abadi, A, Finlayson, J, Ramilan, T, Liu, DL, Anwar, MR, Clark, S, Robertson, S, Mendham, D, Thomas, Q & McGrath, J 2013, EverFarm® – Climate adapted perennial-based farming systems for dryland agriculture in southern Australia, National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility, Gold Coast, 147 pp. -

PROVOCATION’: READRESSING the LANDMARK THAT OUTFLANKED the LAW of MURDER – a COMMENT on ‘REGINA V

Indian Journal of Legal Research & Advancements Volume 1 Issue 1, October 2020 EXPATIATION OF ‘PROVOCATION’: READRESSING THE LANDMARK THAT OUTFLANKED THE LAW OF MURDER – A COMMENT ON ‘REGINA v. Kiranjit Ahluwalia’ Ritik Gupta* ABSTRACT Metaphorically, understanding with practicality makes the concept more explicable, and the same did the case of Regina v. Kiranjit Ahluwalia (“Ahluwalia”) on which the author will be commenting in this piece. Firstly, he will expound that how this judgment broadened the compass of ‘provocation’ and influenced the whole world through a new facet respecting domestic violence and then how the three appeals performed the interrogator, that grilled the legitimacy of directions placed in the precedents in conformance with the contemporary law. Secondly, he will scrutinise the fluctuations escorted due to the inducement of this watershed moment to statues and acts and why those became desiderata to bring into effect. Thirdly, he will draw a distinction in the context of ‘provocation’ and ‘diminished responsibility’ amongst English and Indian law, and discourse that why the latter needs an overhaul. Further, he will tag the tribulations which women have to bear when the law does not perceive the circumstance in all facets. Lastly, he will conclude in a concise way and portray the remainder. TABLE OF CONTENTS * The author is a student of B.A. LL.B. (Hons.) at Fairfield Institute of Management and Technology, GGSIP University, New Delhi. He may be reached at [email protected]. The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the institution’s with which the author is affiliated.