Writingthis Pla Ce

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stormwater Management Plan 2012-17

Stormwater Management Plan 2012-17 City of Whittlesea Stormwater Management Plan: 2012-2017 Copyright © 2012 City of Whittlesea Copyright of materials within this report is owned by or licensed to the City of Whittlesea. Apart from fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under copyright legislation, no part may be reproduced or reused for any commercial purposes whatsoever. Contact [email protected] phone (03) 9217 2170 postal address | Locked Bag 1, Bundoora MDC, 3083 Responsible Council Department Infrastructure Department | Environmental Operations Unit Council Endorsement Council Meeting: 17 Apr 2012 Table of Contents Abbreviations & Acronyms .............................................................................................................. 3 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ 4 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 5 Background ..................................................................................................................................... 6 Stormwater Management Plan 2003 ............................................................................................ 6 Stormwater Management Plan 2007-10 ....................................................................................... 6 Policy and Strategy Context ........................................................................................................... -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL FIFTY-SIXTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION Tuesday, 13 March 2007 (Extract from book 4) Internet: www.parliament.vic.gov.au/downloadhansard By authority of the Victorian Government Printer The Governor Professor DAVID de KRETSER, AC The Lieutenant-Governor The Honourable Justice MARILYN WARREN, AC The ministry Premier, Minister for Multicultural Affairs and Minister for Veterans’ Affairs.............................................. The Hon. S. P. Bracks, MP Deputy Premier and Minister for Water, Environment and Climate Change...................................................... The Hon. J. W. Thwaites, MP Minister for Education............................................ The Hon. J. Lenders, MLC Minister for Skills, Education Services and Employment and Minister for Women’s Affairs................................... The Hon. J. M. Allan, MP Minister for Gaming, Minister for Consumer Affairs and Minister assisting the Premier on Multicultural Affairs ..................... The Hon. D. M. Andrews, MP Minister for Victorian Communities and Minister for Energy and Resources.................................................... The Hon. P. Batchelor, MP Treasurer, Minister for Regional and Rural Development and Minister for Innovation......................................... The Hon. J. M. Brumby, MP Minister for Police and Emergency Services and Minister for Corrections................................................... The Hon. R. G. Cameron, MP Minister for Agriculture.......................................... -

Regional Bird Monitoring Annual Report 2018-2019

BirdLife Australia BirdLife Australia (Royal Australasian Ornithologists Union) was founded in 1901 and works to conserve native birds and biological diversity in Australasia and Antarctica, through the study and management of birds and their habitats, and the education and involvement of the community. BirdLife Australia produces a range of publications, including Emu, a quarterly scientific journal; Wingspan, a quarterly magazine for all members; Conservation Statements; BirdLife Australia Monographs; the BirdLife Australia Report series; and the Handbook of Australian, New Zealand and Antarctic Birds. It also maintains a comprehensive ornithological library and several scientific databases covering bird distribution and biology. Membership of BirdLife Australia is open to anyone interested in birds and their habitats, and concerned about the future of our avifauna. For further information about membership, subscriptions and database access, contact BirdLife Australia 60 Leicester Street, Suite 2-05 Carlton VIC 3053 Australia Tel: (Australia): (03) 9347 0757 Fax: (03) 9347 9323 (Overseas): +613 9347 0757 Fax: +613 9347 9323 E-mail: [email protected] Recommended citation: BirdLife Australia (2020). Melbourne Water Regional Bird Monitoring Project. Annual Report 2018-19. Unpublished report prepared by D.G. Quin, B. Clarke-Wood, C. Purnell, A. Silcocks and K. Herman for Melbourne Water by (BirdLife Australia, Carlton) This report was prepared by BirdLife Australia under contract to Melbourne Water. Disclaimers This publication may be of assistance to you and every effort has been undertaken to ensure that the information presented within is accurate. BirdLife Australia does not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence that may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. -

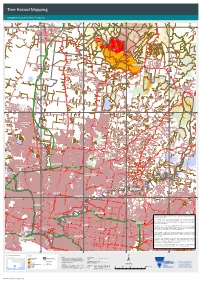

Tree Hazard Mapping

Tree Hazard Mapping Kangaroo Ground L3 ICC Footprint 320000.000000 330000.000000 340000.000000 350000.000000 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 . 0 0 0 0 N 0 0 O 0 0 R 6 6 T 8 8 H 5 5 E R N H I G H W A Y WALLAN Wattle Gully Y A W H G I Dry Creek H N R E H T R O N Chyser Creek Stony Creek Toorourrong Reservoir KINGLAKE WEST Johnson Creek Porcupine Gully Creek Halse Creek Scrubby Creek Pheasant Creek WHITTLESEA Number Three Creek Merri Creek Number One Creek KINGLAKE Recycle Dam Y A W E E R F E M U H Yan Yean Reservoir 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 . 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Darebin Creek 0 4 4 8 8 5 Malcolm Creek 5 Aitken Creek CRAIGIEBURN ST ANDREWS Plenty River H U M E H I G H W A Y H U M E H I Red Shirt Gully Creek G H Greenvale Reservoir W A Y St Clair Reservoir HURSTBRIDGE Brodie Lake The Shankland Reservoir EPPING CHRISTMAS HILLS Yuroke Creek Sugarloaf Reservoir Blue Lake DIAMOND CREEK T U L THOMASTOWN L A M A METR R OPOLITAN RIN IN G ROAD E BROADMEADOWS F D R A E O E D R W G ROA A N RIN Y LITA T Y TROPO S ME N E Y L D P N E Y R O A TULLAMARINE D D A S D O Y A R D O GREENSBOROUGH G N R N I E Y R Y T N N R A R E I E O L R T P A P S E D O W R T D R I V D Edwardes Lake E A O ELTHAM R Biological Lake D G Y N A I A Upper Lake O R W R N R E H E E T G S R U E F W O E R N I O R Sports Fields Lake B A S M N A E L E L R C U A G LDE T R F RE EW WARRANDYTE AY CALDER FREEWAY Chirnside Park Drain COBURG PRESTON 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Mullum Mullum Creek 0 0 0 . -

BULLETIN7 NOVEMBER 2004 Environmental Indicators for Metropolitan Melbourne What’S Inside • Air Emissions

BULLETIN7 NOVEMBER 2004 Environmental Indicators For Metropolitan Melbourne What’s Inside • Air Emissions • Water • Beach and Bay • Greenhouse • Open Space • Waste AUSTRALIAN INSTITUTE OF URBAN STUDIES & CITY OF MELBOURNE METROPOLITAN MELBOURNE PROFILE source: Department of Infrastructure 1998. Metropolitan Melbourne covers 8,833 square kilometres. There are 31 Local Governments (municipalities) within the metropolitan Melbourne region. Region Local Government Area Area (square kilometres) Estimated Residential Population density Population, June 2003 (population per km2) Central Melbourne 36.1 58 031 1 607.5 Port Phillip 20.7 82 331 3 977.3 Yarra 19.5 69 536 3 565.9 Total 76.3 209 898 2 751 Inner Boroondara 60.2 157 888 2 622.7 Darebin 53.5 127 321 2 379.8 Glen Eira 38.7 122 770 3 172.4 Maribyrnong 31.2 61 863 1 982.8 Moonee Valley 44.3 109 567 2 473.3 Moreland 50.9 135 762 2 667.2 Stonnington 25.6 90 197 3 523.3 Total 304.4 805 368 2 645.8 Middle Banyule 62.6 118 149 1 887.4 Bayside 37 89 330 2 414.3 Brimbank 123.4 172 995 1 401.9 Greater Dandenong 129.7 127 380 982.1 Hobsons Bay 64.4 83 585 1 297.9 Kingston 91.1 135 997 1 492.8 Knox 113.9 150 157 1 318.3 Manningham 113.3 114 198 1 007.9 Monash 61.4 161 841 2 635.8 Maroondah 81.5 100 801 1 236.8 Whitehorse 64.3 145 455 2 262.1 Total 942.6 1 399 888 1 485.1 Outer Cardinia 1,281.6 51 290 40 Casey 409.9 201 913492.6 Frankston 129.6 117 079 903.4 Hume 503.8 144 314286.5 Melton 527.6 65 507124.2 Mornington Peninsula 723.6 137 467 190 Nillumbik 430.4 60 585 140.8 Whittlesea 489.4 123 397252.1 -

Cycling Victoria State Facilities Strategy 2016–2026

CYCLING VICTORIA STATE FACILITIES STRATEGY 2016–2026 CONTENTS CONTENTS WELCOME 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2 INTRODUCTION 4 CONSULTATION 8 DEMAND/NEED ASSESSMENT 10 METRO REGIONAL OFF ROAD CIRCUITS 38 IMPLEMENTATION PLAN 44 CYCLE SPORT FACILITY HIERARCHY 50 CONCLUSION 68 APPENDIX 1 71 APPENDIX 2 82 APPENDIX 3 84 APPENDIX 4 94 APPENDIX 5 109 APPENDIX 6 110 WELCOME 1 through the Victorian Cycling Facilities Strategy. ictorians love cycling and we want to help them fulfil this On behalf of Cycling Victoria we also wish to thank our Vpassion. partners Sport and Recreation Victoria, BMX Victoria, Our vision is to see more people riding, racing and watching Mountain Bike Australia, our clubs and Local Government in cycling. One critical factor in achieving this vision will be developing this plan. through the provision of safe, modern and convenient We look forward to continuing our work together to realise facilities for the sport. the potential of this strategy to deliver more riding, racing and We acknowledge improved facilities guidance is critical to watching of cycling by Victorians. adding value to our members and that facilities underpin Glen Pearsall our ability to make Victoria a world class cycling state. Our President members face real challenges at all levels of the sport to access facilities in a safe, local environment. We acknowledge improved facilities guidance is critical to adding value to our members and facilities underpin our ability to make Victoria a world class cycling state. Facilities not only enable growth in the sport, they also enable broader community development. Ensuring communities have adequate spaces where people can actively and safely engage in cycling can provide improved social, health, educational and cultural outcomes for all. -

Strategic Directions Statement September 2018

Yarra STRATEGIC DIRECTIONS STATEMENT SEPTEMBER 2018 Integrated Water Management Forums Acknowledgement of Victoria’s Aboriginal communities The Victorian Government proudly acknowledges Victoria's Aboriginal communities and their rich culture and pays its respects to their Elders past and present. The government also recognises the intrinsic connection of Traditional Owners to Country and acknowledges their contribution to the management of land, water and resources. We acknowledge Aboriginal people as Australia’s fi rst peoples and as the Traditional Owners and custodians of the land and water on which we rely. We recognise and value the ongoing contribution of Aboriginal people and communities to Victorian life and how this enriches us. We embrace the spirit of reconciliation, working towards the equality of outcomes and ensuring an equal voice. © The State of Victoria Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning 2018 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence. You are free to re-use the work under that licence, on the condition that you credit the State of Victoria as author. The licence does not apply to any images, photographs or branding, including the Victorian Coat of Arms, the Victorian Government logo and the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP) logo. To view a copy of this licence, visit creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Printed by Finsbury Green, Melbourne ISSN 2209-8194 - Print format ISSN 2209-8208 - Online Disclaimer This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without fl aw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence which may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. -

Watershed: Towards a Water Sensitive Darebin Strategy

WATERSHED: TOWARDS A WATER SENSITIVE DAREBIN Darebin City Council Whole of Water Cycle Management Strategy 2015-2025 Bundoora Park Acknowledgements Darebin City Council acknowledges the Wurundjeri people as the traditional landowners and the historical and contemporary custodians of the land on which the City of Darebin and surrounding municipalities are located. Strategy Development This project has been assisted by the Victorian Government through Melbourne Water Corporation as part of the Living Rivers Stormwater Program. Stakeholder Consultation Council consulted with many others on this strategy including committees, groups, organisations, agencies, individuals and councils. This includes the following stakeholders: • Melbourne Water www.melbournewater.com.au • Yarra Valley Water www.yvw.com.au • Office of Living Victoria www.depi.vic.gov.au • EPA Victoria www.epa.vic.gov.au • Monash University www.monash.edu • La Trobe University www.latrobe.edu.au • Merri Creek Management Committee www.mcmc.org.au • Darebin Creek Management Committee www.dcmc.org.au • Friends of Merri Creek www.friendsofmerricreek.org.au • Friends of Darebin Creek www.friendsofdarebincreek.org.au • Friends of Edgars Creek www.foec.org.au • Friends of Edwardes Lake (no website) email: [email protected] • Yarra Riverkeepers Association www.yarrariver.org.au • City of Banyule www.banyule.vic.gov.au • City of Whittlesea www.whittlesea.vic.gov.au • City of Moreland www.moreland.vic.gov.au • City of Yarra www.yarracity.vic.gov.au • City of Hume www.hume.vic.gov.au • City -

Housing Opportunities Report

HOUSING OPPORTUNITIES REPORT Strategic Planning Unit City Development Darebin City Council Housing Opportunities Report DISCLAIMER Any representation, statement, opinion or advice expressed or implied in this public is made in good faith but on the basis that the City of Darebin, its agents and employees are not liable (whether by reason of negligence, lack of care or otherwise) to any person for any damages or loss whatsoever which has occurred or may occur in relation to that person taking action in respect to representation, statement, or advice referred to above. The information contained in this document is to be solely used for the purposes of the Darebin Housing Strategy. Any use of the data contained in this document will require a prior written approval from the Strategic Planning Unit of Darebin City Council. 1 Housing Opportunities Report This report has been peer reviewed by the RMIT AHURI Research Centre 2 Housing Opportunities Report Table of Contents ACRONYMS ....................................................................................................5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................6 1 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................12 2 RESIDENTIAL DEVELOPMENT IN DAREBIN.......................................14 2.1 Dwelling Stock and Growth in Darebin ............................................14 2.2 Vacant Land in Darebin ...................................................................15 3 NORTHCOTE -

Liveability and the Vegetated Urban Landscape

LIVEABILITY AND THE VEGETATED URBAN LANDSCAPE An investigation of opportunities for water-related interventions to drive improved liveability in metropolitan Melbourne August 2015 LIVEABILITY AND THE VEGETATED URBAN LANDSCAPE Acknowledgements Urban Initiatives Pty Ltd., an urban design and landscape architecture practice based in Melbourne, led a consortium to undertake the project. The consultant team included: Aquatic Systems Management (whole of water cycle and stormwater management) Homewood Consulting (arboriculture, vegetation assessment) G & M Connellan Consultants (irrigation management) Van De Graaff and Associates (soil science expertise) Fifth Creek Studio (urban heat management and preventative health) Paroissien Grant and Associates (contemporary subdivisional servicing advice) Environment & Land Management Pty Ltd. (town planning, planning regulation). Urban Initiatives Project Manager: Kate Heron Urban Initiatives Pty. Ltd. would also like to acknowledge the significant contributions of David Taylor (City of Yarra, formerly DELWP), Chris Porter (DELWP), Nicky Kindler (Melbourne Water) and Andrew Brophy. Members of project Technical Working Group: Anne Barker (City West Water Ben Harries (Whittlesea CC) Caitlin Keating (MPA) – chair) Clare Lombardi & Simon Sarah Buckley & Jennifer Lee Greg Moore (University of Wilkinson (GTW & CWW) (Stonnington CC) Melbourne Mark Hammett (Moonee Jason Summers (Hume CC) Alan Watts (SEW) Valley CC) Yvonne Lynch (Melbourne Peter May (University of Kein Gan & Simon Newberry CC) Melbourne -

Victoria's Post 1940S Migration Heritage

Victoria’s Post 1940s Migration Heritage Volume 1: Project Report August 2011 Prepared for Heritage Victoria Context Pty Ltd Core Project Team Chris Johnston: Context Sarah Rood: Way Back When Leo Martin: Context Dr Linda Young: Deakin University Jessie Briggs: Context Report Register This report register documents the development and issue of the report entitled Victoria’s Post 1940s Migration Heritage undertaken by Context Pty Ltd in accordance with our internal quality management system. Project Issue Notes/description Issue date Issued to No. No. 1334 1 Vol 1 Project Report (Draft) 23/6/2011 Tracey Avery, Heritage Victoria 1334 2 Vol 1 Project Report (Final) 31/8/2011 Tracey Avery, Heritage Victoria Context Pty Ltd 22 Merri Street, Brunswick 3056 Phone 03 9380 6933 Facsimile 03 9380 4066 Email [email protected] Web www.contextpl.com.au ii CONTENTS SUMMARY V 1 INTRODUCTION 1 Background 1 Purpose 1 Scope 1 Project Plan 2 Report structure 3 Acknowledgements 3 Project team 4 2 VICTORIA’S POST 1940S MIGRATION HERITAGE 5 Developing a thematic history 5 Searching for recognised heritage places, objects and collections 9 3 ENGAGING COMMUNITIES 13 Introduction 13 Principles 13 Development of community-based heritage methods in Australia 18 Examples of methods 24 Definitions 24 Issues 25 Recommended framework 27 Challenges emerging 30 4 THE PILOT PROJECT 32 Background 32 Approach 32 Summary of the case studies 34 Conclusions 42 5 MOVING FORWARD: A STRATEGY FOR ACTION 46 Introduction 46 Opportunities and constraints 46 Proposed action areas 47 BIBLIOGRAPHY 52 Literature searches: notes on the process 56 APPENDIX 1: INVENTORY OF PLACES 58 iii APPENDIX 2: INVENTORY OF OBJECTS AND COLLECTIONS 77 APPENDIX 3: NOTES ON PLACE SEARCHES 84 APPENDIX 4: SAMPLE MUSEUM VICTORIA HOLDINGS (2 EXAMPLES) 90 iv VICTORIA’S POST 1940S MIGRATION HERITAGE SUMMARY Migration is part of Australia’s story, and post-war migration changed the country is fundamental and far reaching ways. -

Parliament of Victoria Parliamentary Debates

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) ASSEMBLY SESSIONAL INDEX FIFTY-FIFTH PARLIAMENT SPRING 2004 Volumes 463 and 464 24 August to 9 December 2004 Internet: www.parliament.vic.gov.au/downloadhansard By authority of the Victorian Government Printer The Governor JOHN LANDY, AC, MBE The Lieutenant-Governor Lady SOUTHEY, AM The ministry Premier and Minister for Multicultural Affairs ....................... The Hon. S. P. Bracks, MP Deputy Premier, Minister for Environment, Minister for Water and Minister for Victorian Communities.............................. The Hon. J. W. Thwaites, MP Minister for Finance and Minister for Consumer Affairs............... The Hon. J. Lenders, MLC Minister for Education Services and Minister for Employment and Youth Affairs....................................................... The Hon. J. M. Allan, MP Minister for Transport and Minister for Major Projects................ The Hon. P. Batchelor, MP Minister for Local Government and Minister for Housing.............. The Hon. C. C. Broad, MLC Treasurer, Minister for Innovation and Minister for State and Regional Development......................................... The Hon. J. M. Brumby, MP Minister for Agriculture........................................... The Hon. R. G. Cameron, MP Minister for Planning, Minister for the Arts and Minister for Women’s Affairs................................... The Hon. M. E. Delahunty, MP Minister for Community Services.................................. The Hon. S. M. Garbutt, MP Minister for Police and Emergency