Victoria's Post 1940S Migration Heritage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

St Vincent's Hospital Melbourne

St Vincent’s Hospital Melbourne – Aikenhead Wing Proposed demolition Referral report and Heritage Impact Statement 27 & 31 Victoria Parade, Fitzroy July 2021 Prepared by Prepared for St Vincent’s Hospital Melbourne Quality Assurance Register The following quality assurance register documents the development and issue of this report prepared by Lovell Chen Pty Ltd in accordance with our quality management system. Project no. Issue no. Description Issue date Approval 8256.03 1 Draft for review 24 June 2021 PL/MK 8256.03 2 Final Referral Report and HIS 1 July 2021 PL Referencing Historical sources and reference material used in the preparation of this report are acknowledged and referenced as endnotes or footnotes and/or in figure captions. Reasonable effort has been made to identify and acknowledge material from the relevant copyright owners. Moral Rights Lovell Chen Pty Ltd asserts its Moral right in this work, unless otherwise acknowledged, in accordance with the (Commonwealth) Copyright (Moral Rights) Amendment Act 2000. Lovell Chen’s moral rights include the attribution of authorship, the right not to have the work falsely attributed and the right to integrity of authorship. Limitation Lovell Chen grants the client for this project (and the client’s successors in title) an irrevocable royalty- free right to reproduce or use the material from this report, except where such use infringes the copyright and/or Moral rights of Lovell Chen or third parties. This report is subject to and issued in connection with the provisions of the agreement between Lovell Chen Pty Ltd and its Client. Lovell Chen Pty Ltd accepts no liability or responsibility for or in respect of any use of or reliance upon this report by any third party. -

Cornishness and Englishness: Nested Identities Or Incompatible Ideologies?

CORNISHNESS AND ENGLISHNESS: NESTED IDENTITIES OR INCOMPATIBLE IDEOLOGIES? Bernard Deacon (International Journal of Regional and Local History 5.2 (2009), pp.9-29) In 2007 I suggested in the pages of this journal that the history of English regional identities may prove to be ‘in practice elusive and insubstantial’.1 Not long after those words were written a history of the north east of England was published by its Centre for Regional History. Pursuing the question of whether the north east was a coherent and self-conscious region over the longue durée, the editors found a ‘very fragile history of an incoherent and barely self-conscious region’ with a sense of regional identity that only really appeared in the second half of the twentieth century.2 If the north east, widely regarded as the most coherent English region, lacks a historical identity then it is likely to be even more illusory in other regions. Although rigorously testing the past existence of a regional discourse and finding it wanting, Green and Pollard’s book also reminds us that history is not just about scientific accounts of the past. They recognise that history itself is ‘an important element in the construction of the region … Memory of the past is deployed, selectively and creatively, as one means of imagining it … We choose the history we want, to show the kind of region we want to be’.3 In the north east that choice has seemingly crystallised around a narrative of industrialization focused on the coalfield and the gradual imposition of a Tyneside hegemony over the centuries following 1650. -

C:\Documents and Settings\Chris Dunkerley\My Documents\Excel

CORNISH ASSOCIATION OF NSW - MEMBERS LENDING & RESEARCH LIBRARY - Jan 2008 Search using Edit, Find in this page (Firefox) For more information or to borrow contact Eddie or Eileen Lyon on: (02) 9349 1491 or Email: [email protected] Id No BOOK NAME AUTHOR DESCRIPTION 1 Yesterday's Town: St Ives Noall Cyril Book - illustrated history 2 King Arthur Country in Cornwall Duxbury & Williams Book - information 3 Story of St Ives, The Noall Cyril Book 4 St Ives in the 1800's Laity R.P. Book 5 Cornish Surnames, A Handbook of G. Pawley White Book 6 Cornish Pioneers of Ballarat Dell & Menhennet Book 7 Kernewek for Kids Franklin Sharon Book - Copper Triangle Puzzles, Stories 8 Australian Celtic Journal Vol.One Darlington J Journal 9 Microform Collection Index (OUT OF CIRCULATION) Aust. Soc of Genealogy Journal 10 Where Now Cousin Jack? Hopkins Ruth Book 11 Cornwall - A Genealogical Bibliography Raymond Stuart Journal LOST 12 Penwith - The Illustrated Past Noall Cyril Book 13 St Ives, The Book of Noall Cyril Book - pictorial history LOST IN FIRE 14 Cornish Names Dexter T.F.G. Book 15 Scilly and the Scillonians Read A.H. & Son Book - pictorial history 16 Shipwrecks at Land's End Larn & Mills Book 17 Minerals, Rocks and Gemstones in Cornwall Rogers Cedric Book - collector’s guide 18 King Arthur, Tintagel Castle & Celtic Monuments Tintagel Parish Council Book 19 Shipwrecks on the Isles of Scilly Gibson F.E. Book 20 Which Francis Symonds Symonds John Symonds history - Cornwall and Australia 21 St Ives, The Beauty of Badger H.G. Illustration Booklet 22 Little Land of Cornwall, The Rowse A.L. -

Stormwater Management Plan 2012-17

Stormwater Management Plan 2012-17 City of Whittlesea Stormwater Management Plan: 2012-2017 Copyright © 2012 City of Whittlesea Copyright of materials within this report is owned by or licensed to the City of Whittlesea. Apart from fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under copyright legislation, no part may be reproduced or reused for any commercial purposes whatsoever. Contact [email protected] phone (03) 9217 2170 postal address | Locked Bag 1, Bundoora MDC, 3083 Responsible Council Department Infrastructure Department | Environmental Operations Unit Council Endorsement Council Meeting: 17 Apr 2012 Table of Contents Abbreviations & Acronyms .............................................................................................................. 3 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ 4 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 5 Background ..................................................................................................................................... 6 Stormwater Management Plan 2003 ............................................................................................ 6 Stormwater Management Plan 2007-10 ....................................................................................... 6 Policy and Strategy Context ........................................................................................................... -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL FIFTY-SIXTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION Tuesday, 13 March 2007 (Extract from book 4) Internet: www.parliament.vic.gov.au/downloadhansard By authority of the Victorian Government Printer The Governor Professor DAVID de KRETSER, AC The Lieutenant-Governor The Honourable Justice MARILYN WARREN, AC The ministry Premier, Minister for Multicultural Affairs and Minister for Veterans’ Affairs.............................................. The Hon. S. P. Bracks, MP Deputy Premier and Minister for Water, Environment and Climate Change...................................................... The Hon. J. W. Thwaites, MP Minister for Education............................................ The Hon. J. Lenders, MLC Minister for Skills, Education Services and Employment and Minister for Women’s Affairs................................... The Hon. J. M. Allan, MP Minister for Gaming, Minister for Consumer Affairs and Minister assisting the Premier on Multicultural Affairs ..................... The Hon. D. M. Andrews, MP Minister for Victorian Communities and Minister for Energy and Resources.................................................... The Hon. P. Batchelor, MP Treasurer, Minister for Regional and Rural Development and Minister for Innovation......................................... The Hon. J. M. Brumby, MP Minister for Police and Emergency Services and Minister for Corrections................................................... The Hon. R. G. Cameron, MP Minister for Agriculture.......................................... -

Heritage Precincts: History and Significance

MELBOURNE PLANNING SCHEME TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 4 1 The City of Melbourne 5 Background History 5 City of Melbourne Summary Statement of Significance 11 2. Carlton Heritage Precinct 13 Background History 13 Statement of Significance for Carlton Heritage Precinct 16 3. East Melbourne Heritage Precinct including Jolimont and the Parliamentary Precinct 19 Background History 19 0 Statement of Significance for East Melbourne Heritage Precinct including Jolimont and the Parliamentary Precinct 22 4. Kensington & Flour Milling Heritage Precinct 27 Background History 27 Statement of Significance for Kensington & Flour Milling Heritage Precinct 29 5. North & West Melbourne Heritage Precinct 31 Background History 31 Statement of Significance for North & West Melbourne Heritage Precinct 34 6. Parkville Heritage Precinct 37 Background History 37 Statement of Significance for Perky'Ile Heritage Precinct 40 7. South Yarra Heritage Precinct 43 Background History 43 Statement of Significance for South Yarra Heritage Precinct 46 8. Bank Place Heritage Precinct 50 Background History 50 Statement of Significance for Bank Place Heritage Precinct 52 9. Bourke Hill Heritage Precinct 54 Background History 54 Statement of Significance for Bourke Hill Heritage Precinct 56 10. Collins Street East Heritage Precinct59 Background History 59 Statement of Significance for Collins Street East Heritage Precinct 61 REFERENCE DOCUMENT - PAGE 2 OF 94 MELBOURNE PLANNING SCHEME 11. Flinders Lane Heritage Precinct 64 Background History 64 Statement of Significance for Flinders Lane Heritage Precinct 65 12. Flinders Street Heritage Precinct 68 Background History 68 Statement of Significance for Flinders Street Heritage Precinct 69 13. Guildford Lane Heritage Precinct 72 Background History 72 Statement of Significance for Guildford Lane Heritage Precinct 73 14. -

Regional Bird Monitoring Annual Report 2018-2019

BirdLife Australia BirdLife Australia (Royal Australasian Ornithologists Union) was founded in 1901 and works to conserve native birds and biological diversity in Australasia and Antarctica, through the study and management of birds and their habitats, and the education and involvement of the community. BirdLife Australia produces a range of publications, including Emu, a quarterly scientific journal; Wingspan, a quarterly magazine for all members; Conservation Statements; BirdLife Australia Monographs; the BirdLife Australia Report series; and the Handbook of Australian, New Zealand and Antarctic Birds. It also maintains a comprehensive ornithological library and several scientific databases covering bird distribution and biology. Membership of BirdLife Australia is open to anyone interested in birds and their habitats, and concerned about the future of our avifauna. For further information about membership, subscriptions and database access, contact BirdLife Australia 60 Leicester Street, Suite 2-05 Carlton VIC 3053 Australia Tel: (Australia): (03) 9347 0757 Fax: (03) 9347 9323 (Overseas): +613 9347 0757 Fax: +613 9347 9323 E-mail: [email protected] Recommended citation: BirdLife Australia (2020). Melbourne Water Regional Bird Monitoring Project. Annual Report 2018-19. Unpublished report prepared by D.G. Quin, B. Clarke-Wood, C. Purnell, A. Silcocks and K. Herman for Melbourne Water by (BirdLife Australia, Carlton) This report was prepared by BirdLife Australia under contract to Melbourne Water. Disclaimers This publication may be of assistance to you and every effort has been undertaken to ensure that the information presented within is accurate. BirdLife Australia does not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence that may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. -

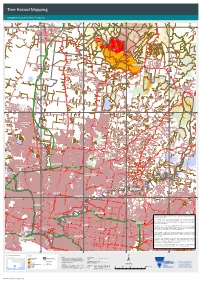

Tree Hazard Mapping

Tree Hazard Mapping Kangaroo Ground L3 ICC Footprint 320000.000000 330000.000000 340000.000000 350000.000000 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 . 0 0 0 0 N 0 0 O 0 0 R 6 6 T 8 8 H 5 5 E R N H I G H W A Y WALLAN Wattle Gully Y A W H G I Dry Creek H N R E H T R O N Chyser Creek Stony Creek Toorourrong Reservoir KINGLAKE WEST Johnson Creek Porcupine Gully Creek Halse Creek Scrubby Creek Pheasant Creek WHITTLESEA Number Three Creek Merri Creek Number One Creek KINGLAKE Recycle Dam Y A W E E R F E M U H Yan Yean Reservoir 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 . 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Darebin Creek 0 4 4 8 8 5 Malcolm Creek 5 Aitken Creek CRAIGIEBURN ST ANDREWS Plenty River H U M E H I G H W A Y H U M E H I Red Shirt Gully Creek G H Greenvale Reservoir W A Y St Clair Reservoir HURSTBRIDGE Brodie Lake The Shankland Reservoir EPPING CHRISTMAS HILLS Yuroke Creek Sugarloaf Reservoir Blue Lake DIAMOND CREEK T U L THOMASTOWN L A M A METR R OPOLITAN RIN IN G ROAD E BROADMEADOWS F D R A E O E D R W G ROA A N RIN Y LITA T Y TROPO S ME N E Y L D P N E Y R O A TULLAMARINE D D A S D O Y A R D O GREENSBOROUGH G N R N I E Y R Y T N N R A R E I E O L R T P A P S E D O W R T D R I V D Edwardes Lake E A O ELTHAM R Biological Lake D G Y N A I A Upper Lake O R W R N R E H E E T G S R U E F W O E R N I O R Sports Fields Lake B A S M N A E L E L R C U A G LDE T R F RE EW WARRANDYTE AY CALDER FREEWAY Chirnside Park Drain COBURG PRESTON 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Mullum Mullum Creek 0 0 0 . -

Religion, Cultural Diversity and Safeguarding Australia

Cultural DiversityReligion, and Safeguarding Australia A Partnership under the Australian Government’s Living In Harmony initiative by Desmond Cahill, Gary Bouma, Hass Dellal and Michael Leahy DEPARTMENT OF IMMIGRATION AND MULTICULTURAL AND INDIGENOUS AFFAIRS and AUSTRALIAN MULTICULTURAL FOUNDATION in association with the WORLD CONFERENCE OF RELIGIONS FOR PEACE, RMIT UNIVERSITY and MONASH UNIVERSITY (c) Copyright Commonwealth of Australia 2004 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Commonwealth available from the Department of Communications, Information Technology and the Arts. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Commonwealth Copyright Administration, Intellectual Property Branch, Department of Communications, Information Technology and the Arts, GPO Box 2154, Canberra ACT 2601 or at http:www.dcita.gov.au The statement and views expressed in the personal profiles in this book are those of the profiled person and are not necessarily those of the Commonwealth, its employees officers and agents. Design and layout Done...ByFriday Printed by National Capital Printing ISBN: 0-9756064-0-9 Religion,Cultural Diversity andSafeguarding Australia 3 contents Chapter One Introduction . .6 Religion in a Globalising World . .6 Religion and Social Capital . .9 Aim and Objectives of the Project . 11 Project Strategy . 13 Chapter Two Historical Perspectives: Till World War II . 21 The Beginnings of Aboriginal Spirituality . 21 Initial Muslim Contact . 22 The Australian Foundations of Christianity . 23 The Catholic Church and Australian Fermentation . 26 The Nonconformist Presence in Australia . 28 The Lutherans in Australia . 30 The Orthodox Churches in Australia . -

BULLETIN7 NOVEMBER 2004 Environmental Indicators for Metropolitan Melbourne What’S Inside • Air Emissions

BULLETIN7 NOVEMBER 2004 Environmental Indicators For Metropolitan Melbourne What’s Inside • Air Emissions • Water • Beach and Bay • Greenhouse • Open Space • Waste AUSTRALIAN INSTITUTE OF URBAN STUDIES & CITY OF MELBOURNE METROPOLITAN MELBOURNE PROFILE source: Department of Infrastructure 1998. Metropolitan Melbourne covers 8,833 square kilometres. There are 31 Local Governments (municipalities) within the metropolitan Melbourne region. Region Local Government Area Area (square kilometres) Estimated Residential Population density Population, June 2003 (population per km2) Central Melbourne 36.1 58 031 1 607.5 Port Phillip 20.7 82 331 3 977.3 Yarra 19.5 69 536 3 565.9 Total 76.3 209 898 2 751 Inner Boroondara 60.2 157 888 2 622.7 Darebin 53.5 127 321 2 379.8 Glen Eira 38.7 122 770 3 172.4 Maribyrnong 31.2 61 863 1 982.8 Moonee Valley 44.3 109 567 2 473.3 Moreland 50.9 135 762 2 667.2 Stonnington 25.6 90 197 3 523.3 Total 304.4 805 368 2 645.8 Middle Banyule 62.6 118 149 1 887.4 Bayside 37 89 330 2 414.3 Brimbank 123.4 172 995 1 401.9 Greater Dandenong 129.7 127 380 982.1 Hobsons Bay 64.4 83 585 1 297.9 Kingston 91.1 135 997 1 492.8 Knox 113.9 150 157 1 318.3 Manningham 113.3 114 198 1 007.9 Monash 61.4 161 841 2 635.8 Maroondah 81.5 100 801 1 236.8 Whitehorse 64.3 145 455 2 262.1 Total 942.6 1 399 888 1 485.1 Outer Cardinia 1,281.6 51 290 40 Casey 409.9 201 913492.6 Frankston 129.6 117 079 903.4 Hume 503.8 144 314286.5 Melton 527.6 65 507124.2 Mornington Peninsula 723.6 137 467 190 Nillumbik 430.4 60 585 140.8 Whittlesea 489.4 123 397252.1 -

Cornish Association Library Holdings Excel

Cornish Association of Victoria - Ballarat Branch Library Holdings February 2011 Item Title Author Donated By Remarks 001 St Just's Point Ian Glanville 1 donated by Jean Opie 2nd copy see item No 44 002 Redruth & District Volume two 003 A View from Carn Marh Bob Acton 004 Tales of The Cornish Miners John Vivian 005 C.F.H.S. Journal No 53 Glynis Hendrickson 006 C.F.H.S. Directory 1989 Glynis Hendrickson 007 Newspaper from Kadina S.A. 1989 008 C.F.H.S. Library Holdings 1991 009 The story of Cornish Language P. Berresford Rod Saddler 1991 010 Cornish Simplified Cardar Rod Saddler 1992 011 Cornish Surnames G. Pawley White 012 C.F.H.S. Journal 62 013 Mining in Cornwall J. Trounson 014 Cousin Jack, Man of the Times Ruth Hopkins 015 St Columb Major Census, Burials & Marriages 016 Campaing for Cornwall 1994 017 Cornwall City Council Part 1 018 Cornwall City Council Part 2 019 Cornish Studies Philip Payton 020 Cornish World issue 1 021 Cornish World issue 2 022 Newspaper "The Cornishmen" June 1994 023 Cornish World issue 3 024 Inspirational Cornwall 1995 025 Recipes and Ramblings Ann Butcher, Kenneth F Annaud Joy Menhennet & Lorraine Harvey 026 Remedies & Reminiscences Historical Ann Butcher, Kenneth F Annaud Joy Menhennet & Lorraine Harvey 027 Cornish World issue 4 028 Penioith And Beyond Iris M. Green 029 Superstition and Folklore Michael Williams 030 Cornish World issue 5 031 Ambra Books Catalogue No 104 032 Favorite Cornish Recipes June Kitton 033 Cornish World issue 6 034 Cornish Worldwide 1994 035 Cornish World bumper issue 036 Cornish Worldwide -

2009 Apr Newsletter

KU-RING-GAI HISTORICAL SOCIETY INC. Incorporating the Ku-ring-gai Family History Centre • Patron: The Mayor of Ku-ring-gai Affiliated with the Royal Australian Historical Society, the National Trust of Australia (NSW), The Society of Australian Genealogists, and the NSW & ACT Association of Family History Societies Inc. September 2011 Newsletter Vol. 29 No. 8 PO Box 109 Gordon NSW 2072 • Ph: (02) 9499 4568 • www.khs.org.au • email: [email protected] Rooms: 799 Pacific Highway Gordon Meetings held in the Gordon Library Meeting Room, 799 Pacific Highway Gordon Walter and Marion Griffin: life & work Coming Meetings Alasdair McGregor, trained architect, photographer, artist Grand and author, spoke at our July meeting of his book Next General Meeting Obsessions: the life and work of Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony Griffin. This definitive work has Saturday 17 September 2.00 pm won this year’s National Biography Award. Walter Burley Griffin met Marion Mahony when both worked with Frank Lloyd Wright in Chicago. Marion, a graduate of MIT, was the first female architect licensed to practice, worldwide. She was highly regarded as a draughtsman and illustrator. Griffin, 35 and Mahony, 40, married in 1911, when the international competition for the design of Canberra was under way. Walter’s design, supported by Marion’s drawings, won the competition in 1912. The couple arrived in Australia in 1913 to consult on the design. Difficulties arose early between Griffin, appointed as part-time Federal Capital Director of Design and Construction, and the Design Review board of the Home Affairs Department of our infant Federal government.