City of Darebin Heritage Study Volume 1 Draft Thematic Environmental History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

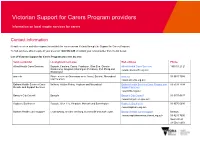

Victorian Support for Carers Program Providers

Victorian Support for Carers Program providers Information on local respite services for carers Contact information Respite services and other support is available for carers across Victoria through the Support for Carers Program. To find out more about respite in your area call 1800 514 845 or contact your local provider from the list below. List of Victorian Support for Carers Program providers by area Service provider Local government area Web address Phone Alfred Health Carer Services Bayside, Cardinia, Casey, Frankston, Glen Eira, Greater Alfred Health Carer Services 1800 51 21 21 Dandenong, Kingston, Mornington Peninsula, Port Phillip and <www.carersouth.org.au> Stonnington annecto Phone service in Grampians area: Ararat, Ballarat, Moorabool annecto 03 9687 7066 and Horsham <www.annecto.org.au> Ballarat Health Services Carer Ballarat, Golden Plains, Hepburn and Moorabool Ballarat Health Services Carer Respite and 03 5333 7104 Respite and Support Services Support Services <www.bhs.org.au> Banyule City Council Banyule Banyule City Council 03 9457-9837 <www.banyule.vic.gov.au> Baptcare Southaven Bayside, Glen Eira, Kingston, Monash and Stonnington Baptcare Southaven 03 9576 6600 <www.baptcare.org.au> Barwon Health Carer Support Colac-Otway, Greater Geelong, Queenscliff and Surf Coast Barwon Health Carer Support Barwon: <www.respitebarwonsouthwest.org.au> 03 4215 7600 South West: 03 5564 6054 Service provider Local government area Web address Phone Bass Coast Shire Council Bass Coast Bass Coast Shire Council 1300 226 278 <www.basscoast.vic.gov.au> -

City of Darebin Aboriginal Community 2009 Early Childhood Community Profile

Early Childhood Community Profile City of Darebin Aboriginal Community 2009 Early Childhood Community Profile City of Darebin Aboriginal Community 2009 This Aboriginal Early childhood community profile was prepared by the Office for Children and Portfolio CdiiCoordination, ini the h ViVictorian i Government G DDepartment of f EdEducation i and d EEarly l ChildhChildhood d DDevelopment. l The series of Early Childhood community profiles draw on data on outcomes for children compiled through the Victorian Child and Adolescent Monitoring System (VCAMS). The profiles are intended to provide local level information on the health, wellbeing, learning, safety and developmental outcomes of young Aboriginal children. They are published to aid Aboriginal organisations and local councils, as well as Best Start partnerships, with local service development, innovation and program planning to improve these outcomes. The Department of Human Services, the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development and the Australian Bureau of Statistics provided data for this document. Aboriginal Early Childhood Community Profile i Published by the Victorian Government DepartmentDepartment of Education and Early Childhood Development, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. January 2010 © Copyright State of Victoria, Department of Education and Early Childhood Development, 2010 This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisionsprovisions of the Copyright Act 19681968.. Principal author and analyst: Hiba -

Environment and Communications Legislation Committee Answers to Questions on Notice Environment Portfolio

Senate Standing Committee on Environment and Communications Legislation Committee Answers to questions on notice Environment portfolio Question No: 3 Hearing: Additional Estimates Outcome: Outcome 1 Programme: Biodiversity Conservation Division (BCD) Topic: Threatened Species Commissioner Hansard Page: N/A Question Date: 24 February 2016 Question Type: Written Senator Waters asked: The department has noted that more than $131 million has been committed to projects in support of threatened species – identifying 273 Green Army Projects, 88 20 Million Trees projects, 92 Landcare Grants (http://www.environment.gov.au/system/files/resources/3be28db4-0b66-4aef-9991- 2a2f83d4ab22/files/tsc-report-dec2015.pdf) 1. Can the department provide an itemised list of these projects, including title, location, description and amount funded? Answer: Please refer to below table for itemised lists of projects addressing threatened species outcomes, including title, location, description and amount funded. INFORMATION ON PROJECTS WITH THREATENED SPECIES OUTCOMES The following projects were identified by the funding applicant as having threatened species outcomes and were assessed against the criteria for the respective programme round. Funding is for a broad range of activities, not only threatened species conservation activities. Figures provided for the Green Army are approximate and are calculated on the 2015-16 indexed figure of $176,732. Some of the funding is provided in partnership with State & Territory Governments. Additional projects may be approved under the Natinoal Environmental Science programme and the Nest to Ocean turtle Protection Programme up to the value of the programme allocation These project lists reflect projects and funding originally approved. Not all projects will proceed to completion. -

Praying Where They Don't Belong

This is a preprint of an article whose final and definitive form has been published in the Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs, vol. 30, no. 2, June 2010, pp 265–278 © 2010 Taylor & Francis; Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs is available online at: www.tandfonline.com with the open URL http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13602004.2010.494076 Praying Where They Don’t Belong: Female Muslim Converts and Mosques in Melbourne, Australia Abstract This paper looks at a sample of women converts to Islam residing in Melbourne, Australia, and their passive boycott of mosques resulting from gender discrimination and ethnic prejudice. Although religious conversion requires structure and support through the performance of religious rituals, including at the community level, Muslim women converts are hindered in their ability to freely access and enjoy mosques. This is despite historical freedom for women to access the Prophet's mosque, and is the result of Islam in Australia being largely characterised by immigrant cultures that assert sex-segregation in the mosque as a way of possessing and ethnicising space. Introduction The mosque plays a central role in the community life of Muslims, and for converts to Islam, observing the rituals of mosque attendance helps facilitate the adoption and confirmation of new Islamic identities; participating in Muslim community rituals helps converts learn to feel, think and act as Muslims.1 Mosques in Australia, having been mostly established by immigrant communities, reflect cultural interpretations of idealised Islamic space. Inadvertently or otherwise, these ethnicised mosques are often exclusionary toward women as well as members of different ethnic groups. -

Stormwater Management Plan 2012-17

Stormwater Management Plan 2012-17 City of Whittlesea Stormwater Management Plan: 2012-2017 Copyright © 2012 City of Whittlesea Copyright of materials within this report is owned by or licensed to the City of Whittlesea. Apart from fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under copyright legislation, no part may be reproduced or reused for any commercial purposes whatsoever. Contact [email protected] phone (03) 9217 2170 postal address | Locked Bag 1, Bundoora MDC, 3083 Responsible Council Department Infrastructure Department | Environmental Operations Unit Council Endorsement Council Meeting: 17 Apr 2012 Table of Contents Abbreviations & Acronyms .............................................................................................................. 3 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ 4 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 5 Background ..................................................................................................................................... 6 Stormwater Management Plan 2003 ............................................................................................ 6 Stormwater Management Plan 2007-10 ....................................................................................... 6 Policy and Strategy Context ........................................................................................................... -

RAA-Belonging Final Lores

BELONG aGREATARTSSTORIES ING FROM REGIONAL AUSTRALIAb written from conversations with aLindy ALLEN SNAPSHOTS based on interviews with aHélène SOBOLEWSKI edited by aMoya SAYER-JONES 2 FOREWORD FOREWORD FOREWORD INTRODUCTION 3 Senator The Hon Tony GRYBOWSKI Dennis GOLDNER Lindy ALLEN George BRANDIS QC CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER PRESIDENT EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR MINISTER FOR THE ARTS Australia Council for the Arts Regional Arts Australia Regional Arts Australia Belonging: Great Arts Stories from Regional Australia Australian artists are ambitious. They inspire us with Welcome to the fifth publication by Regional Arts The process of writing this book was far more complex will be a source of inspiration to artists and communities their storytelling and challenge us to better understand Australia (RAA) of great art stories from regional, remote than I had imagined. A lot of thought goes into across the country. ourselves, our environment and the rich diversity of our and very remote Australia. These collections have proved interviewing people who have created and driven projects nation. They are creative and innovative in their practice to be very effective for RAA in celebrating the stories of with their communities. We were looking for the idea, These remarkable projects demonstrate the important and daring in their vision. It is the work of our artists regionally-based artists and sharing them with those who the passion, the commitment that drives these artists contribution artists make to regional life, and how that will say the most about our time. support us because they understand our value. These and organisers, often against considerable odds, to realise involvement in arts projects can help to build more accounts clearly demonstrate how important the arts are their vision. -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL FIFTY-SIXTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION Tuesday, 13 March 2007 (Extract from book 4) Internet: www.parliament.vic.gov.au/downloadhansard By authority of the Victorian Government Printer The Governor Professor DAVID de KRETSER, AC The Lieutenant-Governor The Honourable Justice MARILYN WARREN, AC The ministry Premier, Minister for Multicultural Affairs and Minister for Veterans’ Affairs.............................................. The Hon. S. P. Bracks, MP Deputy Premier and Minister for Water, Environment and Climate Change...................................................... The Hon. J. W. Thwaites, MP Minister for Education............................................ The Hon. J. Lenders, MLC Minister for Skills, Education Services and Employment and Minister for Women’s Affairs................................... The Hon. J. M. Allan, MP Minister for Gaming, Minister for Consumer Affairs and Minister assisting the Premier on Multicultural Affairs ..................... The Hon. D. M. Andrews, MP Minister for Victorian Communities and Minister for Energy and Resources.................................................... The Hon. P. Batchelor, MP Treasurer, Minister for Regional and Rural Development and Minister for Innovation......................................... The Hon. J. M. Brumby, MP Minister for Police and Emergency Services and Minister for Corrections................................................... The Hon. R. G. Cameron, MP Minister for Agriculture.......................................... -

Moreland History Publications Books

MORELAND HISTORY PUBLICATIONS Some with notes. This list is a work in progress and should not be considered comprehensive. Last updated: 17 December 2012. Most of the following publications can be consulted at Moreland Libraries http://www.moreland.vic.gov.au/moreland-libraries.html Contents: Books Theses Periodicals Newspapers Heritage studies BOOKS Arranged in order of publication, earliest first. Jubilee history of Brunswick : and illustrated handbook of Brunswick and Coburg F.G. Miles Contributor(s): R. A Vivian ; Publisher: Melbourne : Periodicals Publishing Company Date(s): 1907 Description: 119p. : ill., ports. ; 29cm (photocopy). Subjects: City of Moreland, Brunswick (Vic.), Coburg (Vic.) Location: Brunswick Library history room 994.51 JUB Location: Coburg Library history room 994.51 MEL An index concerning the history of Brunswick No author or date. ‘This is an index of persons and subject names concerning the history of Brunswick. The index is based on the “Jubilee history of Brunswick” 1907.’ Location: Brunswick Library history room 994 INDE (SEE ALSO Index of the Jubilee history of Brunswick 1907 prepared by Merle Ellen Stevens 1979) Reports on Coburg Council meetings in local newspapers Oct 1912 to December 1915 No publication date so entered under publication of newspaper. Location: Coburg Library history room 352.09451 REP The City of Coburg : the inception of a new city : 1850-1922. Description [43 leaves] : ill., maps ; 30 cm. Subjects Coburg (Vic.) --History. Location: Coburg Library history room 994.51 CIT Coburg centenary 1839-1939, official souvenir: celebrations August - October, 1939 Walter Mitchell Coburg, Vic : Coburg City Council, 1939. 24 p. : ill., portraits, pbk ; 25 cm. -

The Future of the Yarra

the future of the Yarra ProPosals for a Yarra river Protection act the future of the Yarra A about environmental Justice australia environmental Justice australia (formerly the environment Defenders office, Victoria) is a not-for-profit public interest legal practice. funded by donations and independent of government and corporate funding, our legal team combines a passion for justice with technical expertise and a practical understanding of the legal system to protect our environment. We act as advisers and legal representatives to the environment movement, pursuing court cases to protect our shared environment. We work with community-based environment groups, regional and state environmental organisations, and larger environmental NGos. We also provide strategic and legal support to their campaigns to address climate change, protect nature and defend the rights of communities to a healthy environment. While we seek to give the community a powerful voice in court, we also recognise that court cases alone will not be enough. that’s why we campaign to improve our legal system. We defend existing, hard-won environmental protections from attack. at the same time, we pursue new and innovative solutions to fill the gaps and fix the failures in our legal system to clear a path for a more just and sustainable world. envirojustice.org.au about the Yarra riverkeePer association The Yarra Riverkeeper Association is the voice of the River. Over the past ten years we have established ourselves as the credible community advocate for the Yarra. We tell the river’s story, highlighting its wonders and its challenges. We monitor its health and activities affecting it. -

7.5. Final Outcomes of 2020 General Valuation

Council Meeting Agenda 24/08/2020 7.5 Final outcomes of 2020 General Valuation Abstract This report provides detailed information in relation to the 2020 general valuation of all rateable property and recommends a Council resolution to receive the 1 January 2020 General Valuation in accordance with section 7AF of the Valuation of Land Act 1960. The overall movement in property valuations is as follows: Site Value Capital Improved Net Annual Value Value 2019 Valuations $82,606,592,900 $112,931,834,000 $5,713,810,200 2020 Valuations $86,992,773,300 $116,769,664,000 $5,904,236,100 Change $4,386,180,400 $3,837,830,000 $190,425,800 % Difference 5.31% 3.40% 3.33% The level of value date is 1 January 2020 and the new valuation came into effect from 1 July 2020 and is being used for apportioning rates for the 2020/21 financial year. The general valuation impacts the distribution of rating liability across the municipality. It does not provide Council with any additional revenue. The distribution of rates is affected each general valuation by the movement in the various property classes. The important point from an equity consideration is that all properties must be valued at a common date (i.e. 1 January 2020), so that all are affected by the same market. Large shifts in an individual property’s rate liability only occurs when there are large movements either in the value of a property category (e.g. residential, office, shops, industrial) or the value of certain locations, which are outside the general movements in value across all categories or locations. -

Gladys Nicholls: an Urban Aboriginal Leader in Post-War Victoria

Gladys Nicholls: An Urban Aboriginal Leader in Post-war Victoria Patricia Grimshaw School of Historical and Philosophical Studies, University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC. 3010 [email protected] Abstract: Gladys Nicholls was an Aboriginal activist in mid-20 th century Victoria who made significant contributions to the development of support networks for the expanding urban Aboriginal community of inner-city Melbourne. She was a key member of a talented group of Indigenous Australians, including her husband Pastor Doug Nicholls, who worked at a local, state and national level to improve the economic wellbeing and civil rights of their people, including for the 1967 Referendum. Those who knew her remember her determined personality, her political intelligence and her unrelenting commitment to building a better future for Aboriginal people. Keywords: Aboriginal women, Aboriginal activism, Gladys Nicholls, Pastor Doug Nicholls, assimilation, Victorian Aborigines Advancement League, 1967 Referendum Gladys Nicholls (1906–1981) was an Indigenous leader who was significant from the 1940s to the 1970s, first, in action to improve conditions for Aboriginal people in Melbourne and second, in grassroots activism for Indigenous rights across Australia. When the Victorian government inscribed her name on the Victorian Women’s Honour Roll in 2008, the citation prepared by historian Richard Broome read as follows: ‘Lady Gladys Nicholls was an inspiration to Indigenous People, being a role model for young women, a leader in advocacy for the rights of Indigenous people as well as a tireless contributor to the community’. 1 Her leadership was marked by strong collaboration and co-operation with like-minded women and men, both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal, who were at the forefront of Indigenous reform, including her prominent husband, Pastor (later Sir) Doug Nicholls. -

Tatz MIC Castan Essay Dec 2011

Indigenous Human Rights and History: occasional papers Series Editors: Lynette Russell, Melissa Castan The editors welcome written submissions writing on issues of Indigenous human rights and history. Please send enquiries including an abstract to arts- [email protected]. ISBN 978-0-9872391-0-5 Genocide in Australia: By Accident or Design? Colin Tatz © Indigenous Human Rights and History Vol 1(1). The essays in this series are fully refereed. Editorial committee: John Bradley, Melissa Castan, Stephen Gray, Zane Ma Rhea and Lynette Russell. Genocide in Australia: By Accident or Design? Colin Tatz © Colin Tatz 1 CONTENTS Editor’s Acknowledgements …… 3 Editor’s introduction …… 4 The Context …… 11 Australia and the Genocide Convention …… 12 Perceptions of the Victims …… 18 Killing Members of the Group …… 22 Protection by Segregation …… 29 Forcible Child Removals — the Stolen Generations …… 36 The Politics of Amnesia — Denialism …… 44 The Politics of Apology — Admissions, Regrets and Law Suits …… 53 Eyewitness Accounts — the Killings …… 58 Eyewitness Accounts — the Child Removals …… 68 Moving On, Moving From …… 76 References …… 84 Appendix — Some Known Massacre Sites and Dates …… 100 2 Acknowledgements The Editors would like to thank Dr Stephen Gray, Associate Professor John Bradley and Dr Zane Ma Rhea for their feedback on earlier versions of this essay. Myles Russell-Cook created the design layout and desk-top publishing. Financial assistance was generously provided by the Castan Centre for Human Rights Law and the School of Journalism, Australian and Indigenous Studies. 3 Editor’s introduction This essay is the first in a new series of scholarly discussion papers published jointly by the Monash Indigenous Centre and the Castan Centre for Human Rights Law.