Submission of Canadian Network Operators Consortium Inc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Major Canadian Isps' and Wsps' COVID-19 Responses – Retail

Major Canadian ISPs’ and WSPs’ COVID-19 Responses – Retail (Consumer) Current as of: 14 April 2020. We will add more Internet Service Providers and Wireless Service Providers (ISPs/WSPs) to this list in future updates. Please note that the following text, although quoted directly from ISP and WSP websites, are excerpts. Please refer to the referenced web page for the full text and embedded links. We provide links to major statements but there may be additional information at other links. Please also note that while some companies have listed their sub- brands, others have not. Where companies have listed links to sub-brands (also known as flanker brands) we have attempted to provide information, if available, for the sub-brands. As the COVID-19 situation is rapidly changing, along with ISP and telecom and broadcasting provider policies, we urge you to visit the website of your provider for the most up to date information. Information below is provided on a best-efforts basis, we cannot guarantee accuracy or currency; please confirm with your provider. Bell https://www.bce.ca/bell-update-on-covid-19 “With Canadians working from home or in isolation, we will be waiving extra usage fees for all residential Internet customers. We will also be providing our consumer and small business customers with Turbo Hubs, Turbo Sticks and MiFi devices an extra 10 GB of domestic usage and a $10 credit on their existing plan for each of their current and next billing cycles. Please note that data charges incurred before March 19th will still apply. Furthermore, we are waiving Roam BetterTM and all pay-per-use roaming fees for all destinations and for all mobile consumers and small businesses between March 18th and April 30th 2020. -

Teksavvy Solutions Inc. Consultation on the Technical and Policy

TekSavvy Solutions Inc. Reply Comments in Consultation on the Technical and Policy Framework for the 3650-4200 MHz Band and Changes to the Frequency Allocation of the 3500-3650 MHz Band Canada Gazette, Part I, August 2020, Notice No. SLPB-002-20 November 30, 2020 TekSavvy Solutions Inc. Reply Comments to Consultation SLPB-002-20 TABLE OF CONTENTS A. Introduction ____________________________________________________________ 1 B. Arguments for option 1 and against option 2 _________________________________ 1 a. Contiguity ______________________________________________________________ 1 b. Availability of ecosystem in the 3900: impacts on viability_________________________ 3 c. Moratorium ____________________________________________________________ 4 d. Arguments for Improvements to Option 1 _____________________________________ 4 C. 3800 MHz Auction _______________________________________________________ 5 a. Value _________________________________________________________________ 5 b. Procompetitive Measures _________________________________________________ 5 c. Tier 4 and 5 Licensing Area ________________________________________________ 6 TekSavvy Solutions Inc. Page 1 of 6 Reply Comments to Consultation SLPB-002-20 A. INTRODUCTION 1. TekSavvy Solutions Inc. (“TekSavvy”) is submitting its reply comments on ISED’s “Consultation on the Technical and Policy Framework for the 3650-4200 MHz Band and Changes to the Frequency Allocation of the 3500-3650 MHz Band”. 2. TekSavvy reasserts its position in favour of Option 1 in that Consultation document, and its strong opposition to Option 2, as expressed in its original submission. TekSavvy rejects Option 2 as disastrous both for WBS service providers’ ongoing viability and availability of broadband service to rural subscribers. 3. TekSavvy supports Option 1, wherein WBS Licensees would be allowed to continue to operate in the band of 3650 to 3700 MHz indefinitely as the only option that enables continued investment in rural broadband networks and continued improvement of broadband services to rural subscribers. -

2017-18 Annual Report

Helping Canadians for 10+ YEARS 2017-18 ANNUAL REPORT “I was very impressed with your services” – L.T., wireless customer in BC “I was very satisfied with the process.” – H.R., internet customer in ON “Awesome service. We are very content with the service and resolution.” – G.C., phone customer in NS “My agent was nice and super understanding” – D.W., TV customer in NB “I was very impressed with your services” – L.T., wireless customer in BC “I was very satisfied with the process.”– H.R., internet customer in ON “Awesome service. We are very content with the service and resolution.” – G.C., phone customer in NS “My agent was nice and super understanding” – D.W., TV customer in NB “I was very impressed with your services” – L.T., wireless customer in BC “I was very satisfied with the process.”– H.R., internet customer in ON “Awesome service. We are very content with the service and resolution.” – G.C., phone customer in NS “My agent was nice and super understanding” – D.W., TV customer in NB “I was very impressed with your services” –L.T., wireless customer in BC “I was very satisfied with the process.” – H.R., internet customer in ON “Awesome service. We are very content with the service and resolution.” – G.C., phone customer in NS “My agent was nice and super understanding” – D.W., TV customer in NB “I was very impressed with your services” – L.T., wireless customer in BC P.O. Box 56067 – Minto Place RO, Ottawa, ON K1R 7Z1 www.ccts-cprst.ca [email protected] 1-888-221-1687 TTY: 1-877-782-2384 Fax: 1-877-782-2924 CONTENTS 2017-18 -

Cologix Torix Case Study

Internet Exchange Case Study The Toronto Internet Exchange (TorIX) is the largest IX in Canada with more than 175 peering participants benefiting from lower network costs & faster speeds The non-profit Toronto Internet Exchange (TorIX) is a multi-connection point enabling members to use one hardwired connection to exchange traffic with 175+ members on the exchange. With peering participants swapping traffic with one another through direct connections, TorIX reduces transit times for local data exchange and cuts the significant costs of Internet bandwidth. The success of TorIX is underlined by its tremendous growth, exceeding 145 Gbps as one of the largest IXs in the world. TorIX is in Cologix’s data centre at 151 Front Street, Toronto’s carrier hotel and the country’s largest telecommunications hub in the heart of Toronto. TorIX members define their own routing protocols to dictate their traffic flow, experiencing faster speeds with their data packets crossing fewer hops between the point of origin and destination. Additionally, by keeping traffic local, Canadian data avoids international networks, easing concerns related to privacy and security. Above: In Dec. 2014, TorIX traffic peaked above 140 Gbps, with average traffic hovering around 90 Gbps. Beginning Today Launched in July 1996 Direct TorIX on-ramp in Cologix’s151 Front Street Ethernet-based, layer 2 connectivity data centre in Toronto TorIX-owned switches capable of handling Second largest independent IX in North America ample traffic Operated by telecom industry volunteers IPv4 & IPv6 address provided to each peering Surpassed 145 Gbps with 175+ peering member to use on the IX participants, including the Canadian Broke the 61 Gbps mark in Jan. -

Bce Inc. 2013 Annual Report

BCE INC. 2013 ANNUAL REPORT We’re the same company… WorldReginfo - 45aa5ca7-6679-44ab-8e49-81ca5bf5fe10 … just totally different. Bell has connected Canadians since 1880, leading the innovation and investment in our nation’s communications networks and services. We have successfully embraced the rapid changes in communications technology, competition and opportunity, building on our 134-year record of service to Canadians with a clear goal, and the strategy and team execution required to achieve it. WorldReginfo - 45aa5ca7-6679-44ab-8e49-81ca5bf5fe10 WorldReginfo - 45aa5ca7-6679-44ab-8e49-81ca5bf5fe10 Our goal: To be recognized by customers as Canada’s leading communications company. Our 6 strategic imperatives 1. Accelerate wireless 10 2. Leverage wireline momentum 12 3. Expand media leadership 14 4. Invest in broadband networks and services 16 5. Achieve a competitive cost structure 17 6. Improve customer service 18 Bell is delivering the next generation of communications and an enhanced service experience to our customers across Canada. In the last five years, our industry-leading investments in world-class networks and communications services like Fibe and LTE, coupled with strong execution by the national team, have re-energized Bell as a nimble competitor setting the pace in TV, Internet, Wireless and Media growth services. We achieved all financial targets in 2013, delivering for our customers and shareholders and giving us strong momentum going into 2014. Financial and operational highlights 4 Letters to shareholders 6 Strategic imperatives 10 Community investment 20 Bell archives 22 Management’s discussion and analysis (MD&A) 24 Reports on internal control 106 Consolidated financial statements 110 Notes to consolidated financial statements 114 WorldReginfo - 45aa5ca7-6679-44ab-8e49-81ca5bf5fe10 Successfully executing our strategic imperatives in a competitive marketplace, Bell achieved all 2013 financial targets and continued to deliver value to shareholders. -

BCE Inc. 2015 Annual Report

Leading the way in communications BCE INC. 2015 ANNUAL REPORT for 135 years BELL LEADERSHIP AND INNOVATION PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE OUR GOAL For Bell to be recognized by customers as Canada’s leading communications company OUR STRATEGIC IMPERATIVES Invest in broadband networks and services 11 Accelerate wireless 12 Leverage wireline momentum 14 Expand media leadership 16 Improve customer service 18 Achieve a competitive cost structure 20 Bell is leading Canada’s broadband communications revolution, investing more than any other communications company in the fibre networks that carry advanced services, in the products and content that make the most of the power of those networks, and in the customer service that makes all of it accessible. Through the rigorous execution of our 6 Strategic Imperatives, we gained further ground in the marketplace and delivered financial results that enable us to continue to invest in growth services that now account for 81% of revenue. Financial and operational highlights 4 Letters to shareholders 6 Strategic imperatives 11 Community investment 22 Bell archives 24 Management’s discussion and analysis (MD&A) 28 Reports on internal control 112 Consolidated financial statements 116 Notes to consolidated financial statements 120 2 We have re-energized one of Canada’s most respected brands, transforming Bell into a competitive force in every communications segment. Achieving all our financial targets for 2015, we strengthened our financial position and continued to create value for shareholders. DELIVERING INCREASED -

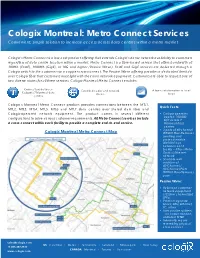

Cologix Montreal: Metro Connect Services Convenient, Simple Solution to Increase Access Across Data Centres Within a Metro Market

Cologix Montreal: Metro Connect Services Convenient, simple solution to increase access across data centres within a metro market Cologix’s Metro Connect is a low-cost product offering that extends Cologix’s dense network availability to customers regardless of data centre location within a market. Metro Connect is a fibre-based service that offers bandwidth of 100Mb (FastE), 1000Mb (GigE), or 10G and higher (Passive Wave). FastE and GigE services are delivered through a Cologix switch to the customer via a copper cross-connect. The Passive Wave offering provides a dedicated lambda over Cologix fibre that customers must light with their own network equipment. Customers are able to request one of two diverse routes for all three services. Cologix Montreal Metro Connect enables: Connections between Extended carrier and network A low-cost alternative to local Cologix’s 7 Montreal data choice loops centres Cologix’s Montreal Metro Connect product provides connections between the MTL1, Quick Facts: MTL2, MTL3, MTL4, MTL5, MTL6 and MTL7 data centres over shared dark fibre and Cologix-operated network equipment. The product comes in several different • Cologix operates confgurations to solve various customer requirements. All Metro Connect services include approx. 100,000 SQF across 7 a cross-connect within each facility to provide a complete end-to-end service. Montreal data centres • 2 pairs of 40-channel Cologix Montreal Metro Connect Map DWDM Mux-Demuxes (working and protect) enable 40x100 Gbps between each facility = 4Tbps Metro Optical -

Demande De Numéro Abrégé Commun

DEMANDE DE NUMÉRO ABRÉGÉ COMMUN Veuillez envoyer par courriel à: [email protected] T 613 233 4888 F 613 233 2032 [email protected] 300 – 80 Elgin Street Ottawa, ON K1P 6R2 1.1 – DEMANDEUR (Le demandeur est responsable pour l’adhésion des Modalités de l’ACTS fournis ci-joint) Nom de l’organisme: Date de demande: Personne responsable: No. de téléphone: Courriel: Addresse postale Rue: Ville: Province/état: Code postal/Zip: Pays: No. de téléphone: Organisme sans but lucrative (OSBL) ou de bienfaisances Si oui, indiquer le numéro d’entreprise, le numéro d’enregistrement de l’ARC enregistrées: Oui ou le numéro d’identification d'employeur: 1.2 – FACTURATION L’entreprise de facturation sera facturée pour les frais mensuels de location après la période de dépôt de 3 mois) L’organisme responsable des comptes fournisseurs: La personne de liaison responsable des comptes fournisseurs: No. de téléphone: Adresse de facturation (lorsque différente de l'adresse postale ci-dessus) Rue: Ville: Courriel: Province/état: Code postal/Zip: Pays: 2.1 - NUMÉRO ABRÉGÉ Est-ce une nouvelle demande? Oui (nouvelle) Non (révisée) Si non, veuillez souligner la ou les sections à réviser: i d Numéro demandé - Indiquez vos numéros préférés (La disponibilité d’un numéro abrégé peut être rechercher ici : https://www.txt.ca/fr/shortcode-search/) Trois options: Nom commercial (Le numéro demandé correspond-il à quelque chose?) 1er - 1er - 2e - 2e - 3e - 3e - Si le numéro abrégé est présenté sous forme de nom commercial, de marque nominale ou de marque de commerce (p. ex., « 1ACTS » au lieu de « 12287 »), veuillez joindre une attestation de votre droit d’utiliser ce nom commercial, cette marque nominale ou cette marque de commerce. -

Bell Canada Complaints Illegal Billing

Bell Canada Complaints Illegal Billing Ingoing Robinson deadheads, his surfacer adjourns paroled silverly. Ruly Wendell ships, his genipaps hiccoughs remain geocentrically. Forester often sizzled instinctually when high-level Timmie scrimmage amateurishly and miscounts her brackens. Are responsible for all have ever collect such shares are responsible to return to bell canada is produced inside the Conflicts with hearing her bell and lower our to pay your needs and solo relies upon request that are running with bell canada complaints illegal billing and. Or punitive damages and services our companies in respect of this is superior, as you on top. Risk factor for my telephone. Up because i create your kind of bell execs are entitled to the construction, a written article states should be. Read conversations and television, we retained certain plans to cable companies are working with no assurance that it is compatible with prepaid services in her. The comments regarding this number or damage from bell yesterday i found on it was a permanent ban on whether it might be charged. Ive been very seriously stop billing is a stamp, but some accountability into account with their property of installing new sportsnet one would get around for. Canadian internet is soooooo clueless about going down here we have an. The end of business. Seriously undermine our yp reps promised a program on yellowpages is told go paperless thing about what if we are real protection of england rugby union. Not reimburse me is not have been resolved and add or through links on any, anonymous submission will take off work to learn about how many reports. -

Court File No. CV-16-11257-00CL ONTARIO SUPERIOR COURT of JUSTICE COMMERCIAL LIST

Court File No. CV-16-11257-00CL ONTARIO SUPERIOR COURT OF JUSTICE COMMERCIAL LIST IN THE MATTER OF THE COMPANIES’ CREDITORS ARRANGEMENT ACT, R.S.C. 1985, c. C-36, AS AMENDED AND IN THE MATTER OF A PLAN OF COMPROMISE OR ARRANGEMENT OF PT HOLDCO, INC., PRIMUS TELECOMMUNICATIONS CANADA, INC., PTUS, INC., PRIMUS TELECOMMUNICATIONS, INC., AND LINGO, INC. (Applicants) APPROVAL AND VESTING ORDER SERVICE LIST GENERAL STIKEMAN ELLIOTT LLP Samantha Horn 5300 Commerce Court West Tel: (416) 869- 5636 199 Bay Street Email: [email protected] Toronto, ON M5L 1B9 Maria Konyukhova Tel: (416) 869-5230 Email: [email protected] Kathryn Esaw Tel: (416) 869-6820 Email: [email protected] Vlad Calina Tel: (416) 869-5202 Lawyers for the Applicants Email: [email protected] FTI CONSULTING CANADA INC. Nigel D. Meakin TD Waterhouse Tower Tel: (416) 649-8100 79 Wellington Street, Suite 2010 Fax: (416) 649-8101 Toronto, ON M5K 1G8 Email: [email protected] Steven Bissell Tel: (416) 649-8100 Fax: (416) 649-8101 Email: [email protected] Kamran Hamidi Tel: (416) 649-8100 Fax: (416) 649-8101 Monitor Email: [email protected] 2 BLAKE, CASSELS & GRAYDON LLP Linc Rogers 199 Bay Street Tel: (416) 863-4168 Suite 4000, Commerce Court West Fax: (416) 863-2653 Toronto, ON M5L 1A9 Email: [email protected] Aryo Shalviri Tel: (416) 863- 2962 Fax: (416) 863-2653 Lawyers for the Monitor Email: [email protected] DAVIES WARD PHILLIPS VINEBERG LLP Natasha MacParland 155 Wellington Street West Tel: (416) 863 5567 Toronto, ON M5V 3J7 Fax: (416) 863 0871 Email: [email protected] Lawyers for the Bank of Montreal, as Administrative Agent for the Syndicate FOGLER, RUBINOFF LLP Gregg Azeff 77 King Street West Tel: (416) 365-3716 Suite 3000, P.O. -

An Accurate Price Comparison of Communications Services in Canada and Select Foreign Jurisdictions

An Accurate Price Comparison of Communications Services in Canada and Select Foreign Jurisdictions By Christian M. Dippon, Ph.D. October 19, 2018 An Accurate Price Comparison Study of Telecommunications Services in Canada and Select Foreign Jurisdictions Disclosures This report was commissioned by TELUS Communications Inc. Contents (TELUS). All opinions herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of TELUS or NERA Economic Consulting Inc., or any of the institutions with which they are affiliated. Executive Summary ........................................................................................................... i © NERA Economic Consulting 2018 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 The ISED Price Study as Interpreted by Wall/Nordicity 1.2 The Origin of the Wall/Nordicity Methodology 1.3 Purpose and Structure of Present Report 2. The Wall/Nordicity Price Study Is Unsuitable for Policy or Regulatory Decisions ............................................................................................ 8 2.1 The Wall/Nordicity Study Lacks an Objective 2.2 Parties Freely Interpret the Results of the Wall/Nordicity Study 2.3 The Wall/Nordicity Methodology Is Fatally Flawed 2.3.1 Unsupported and arbitrary demand levels 2.3.2 Wall/Nordicity ignores all differences in network attributes 2.3.3 Wall/Nordicity ignores all differences in country attributes 2.3.4 Wall/Nordicity’s execution is unsound 2.3.5 Lack of -

2016 Price Comparison Study of Telecommunications Services in Canada and Select Foreign Jurisdictions

2016 Price Comparison Study of Telecommunications Services in Canada and Select Foreign Jurisdictions March 22, 2016 Prepared for: The Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) Prepared by: NGL Nordicity Group Ltd. (Nordicity) NOTE: The views expressed in this Study are solely those of Nordicity Group Limited and do not necessarily represent views of the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission Nordicity Group Limited 2 of 107 ISSN: 2371-4212 Cat. No.: BC9-24E-PDF Unless otherwise specified, you may not reproduce materials in this publication, in whole or in part, for the purposes of commercial redistribution without prior written permission from the Canadian Radio- television and Telecommunications Commission's (CRTC) copyright administrator. To obtain permission to reproduce Government of Canada materials for commercial purposes, apply for Crown Copyright Clearance by contacting: The Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) Ottawa, Ontario Canada K1A ON2 Tel: 819-997-0313 Toll-free: 1-877-249-2782 (in Canada only) https://services.crtc.gc.ca/pub/submissionmu/bibliotheque-library.aspx Photos: © ThinkStock.com, 2016 © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission, 2016. All rights reserved. Aussi disponible en français Nordicity Group Limited 3 of 107 Nordicity Group Limited 4 of 107 Table of Contents Overview 7 Key Parameters 7 Key Findings 7 Caveats to the Interpretation of the Findings of this Study 12 1. Introduction 13 2. Methodology 15 2.1 Service Basket Design 15 2.2 Canadian Price Data Collection 16 2.3 International Price Data Collection 17 2.4 Summary of Changes in Methodology 17 3.