Mapping the Long-Term Options for Canada's North: Telecommunications and Broadband Connectivity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Major Canadian Isps' and Wsps' COVID-19 Responses – Retail

Major Canadian ISPs’ and WSPs’ COVID-19 Responses – Retail (Consumer) Current as of: 14 April 2020. We will add more Internet Service Providers and Wireless Service Providers (ISPs/WSPs) to this list in future updates. Please note that the following text, although quoted directly from ISP and WSP websites, are excerpts. Please refer to the referenced web page for the full text and embedded links. We provide links to major statements but there may be additional information at other links. Please also note that while some companies have listed their sub- brands, others have not. Where companies have listed links to sub-brands (also known as flanker brands) we have attempted to provide information, if available, for the sub-brands. As the COVID-19 situation is rapidly changing, along with ISP and telecom and broadcasting provider policies, we urge you to visit the website of your provider for the most up to date information. Information below is provided on a best-efforts basis, we cannot guarantee accuracy or currency; please confirm with your provider. Bell https://www.bce.ca/bell-update-on-covid-19 “With Canadians working from home or in isolation, we will be waiving extra usage fees for all residential Internet customers. We will also be providing our consumer and small business customers with Turbo Hubs, Turbo Sticks and MiFi devices an extra 10 GB of domestic usage and a $10 credit on their existing plan for each of their current and next billing cycles. Please note that data charges incurred before March 19th will still apply. Furthermore, we are waiving Roam BetterTM and all pay-per-use roaming fees for all destinations and for all mobile consumers and small businesses between March 18th and April 30th 2020. -

Teksavvy Solutions Inc. Consultation on the Technical and Policy

TekSavvy Solutions Inc. Reply Comments in Consultation on the Technical and Policy Framework for the 3650-4200 MHz Band and Changes to the Frequency Allocation of the 3500-3650 MHz Band Canada Gazette, Part I, August 2020, Notice No. SLPB-002-20 November 30, 2020 TekSavvy Solutions Inc. Reply Comments to Consultation SLPB-002-20 TABLE OF CONTENTS A. Introduction ____________________________________________________________ 1 B. Arguments for option 1 and against option 2 _________________________________ 1 a. Contiguity ______________________________________________________________ 1 b. Availability of ecosystem in the 3900: impacts on viability_________________________ 3 c. Moratorium ____________________________________________________________ 4 d. Arguments for Improvements to Option 1 _____________________________________ 4 C. 3800 MHz Auction _______________________________________________________ 5 a. Value _________________________________________________________________ 5 b. Procompetitive Measures _________________________________________________ 5 c. Tier 4 and 5 Licensing Area ________________________________________________ 6 TekSavvy Solutions Inc. Page 1 of 6 Reply Comments to Consultation SLPB-002-20 A. INTRODUCTION 1. TekSavvy Solutions Inc. (“TekSavvy”) is submitting its reply comments on ISED’s “Consultation on the Technical and Policy Framework for the 3650-4200 MHz Band and Changes to the Frequency Allocation of the 3500-3650 MHz Band”. 2. TekSavvy reasserts its position in favour of Option 1 in that Consultation document, and its strong opposition to Option 2, as expressed in its original submission. TekSavvy rejects Option 2 as disastrous both for WBS service providers’ ongoing viability and availability of broadband service to rural subscribers. 3. TekSavvy supports Option 1, wherein WBS Licensees would be allowed to continue to operate in the band of 3650 to 3700 MHz indefinitely as the only option that enables continued investment in rural broadband networks and continued improvement of broadband services to rural subscribers. -

2017-18 Annual Report

Helping Canadians for 10+ YEARS 2017-18 ANNUAL REPORT “I was very impressed with your services” – L.T., wireless customer in BC “I was very satisfied with the process.” – H.R., internet customer in ON “Awesome service. We are very content with the service and resolution.” – G.C., phone customer in NS “My agent was nice and super understanding” – D.W., TV customer in NB “I was very impressed with your services” – L.T., wireless customer in BC “I was very satisfied with the process.”– H.R., internet customer in ON “Awesome service. We are very content with the service and resolution.” – G.C., phone customer in NS “My agent was nice and super understanding” – D.W., TV customer in NB “I was very impressed with your services” – L.T., wireless customer in BC “I was very satisfied with the process.”– H.R., internet customer in ON “Awesome service. We are very content with the service and resolution.” – G.C., phone customer in NS “My agent was nice and super understanding” – D.W., TV customer in NB “I was very impressed with your services” –L.T., wireless customer in BC “I was very satisfied with the process.” – H.R., internet customer in ON “Awesome service. We are very content with the service and resolution.” – G.C., phone customer in NS “My agent was nice and super understanding” – D.W., TV customer in NB “I was very impressed with your services” – L.T., wireless customer in BC P.O. Box 56067 – Minto Place RO, Ottawa, ON K1R 7Z1 www.ccts-cprst.ca [email protected] 1-888-221-1687 TTY: 1-877-782-2384 Fax: 1-877-782-2924 CONTENTS 2017-18 -

Cologix Torix Case Study

Internet Exchange Case Study The Toronto Internet Exchange (TorIX) is the largest IX in Canada with more than 175 peering participants benefiting from lower network costs & faster speeds The non-profit Toronto Internet Exchange (TorIX) is a multi-connection point enabling members to use one hardwired connection to exchange traffic with 175+ members on the exchange. With peering participants swapping traffic with one another through direct connections, TorIX reduces transit times for local data exchange and cuts the significant costs of Internet bandwidth. The success of TorIX is underlined by its tremendous growth, exceeding 145 Gbps as one of the largest IXs in the world. TorIX is in Cologix’s data centre at 151 Front Street, Toronto’s carrier hotel and the country’s largest telecommunications hub in the heart of Toronto. TorIX members define their own routing protocols to dictate their traffic flow, experiencing faster speeds with their data packets crossing fewer hops between the point of origin and destination. Additionally, by keeping traffic local, Canadian data avoids international networks, easing concerns related to privacy and security. Above: In Dec. 2014, TorIX traffic peaked above 140 Gbps, with average traffic hovering around 90 Gbps. Beginning Today Launched in July 1996 Direct TorIX on-ramp in Cologix’s151 Front Street Ethernet-based, layer 2 connectivity data centre in Toronto TorIX-owned switches capable of handling Second largest independent IX in North America ample traffic Operated by telecom industry volunteers IPv4 & IPv6 address provided to each peering Surpassed 145 Gbps with 175+ peering member to use on the IX participants, including the Canadian Broke the 61 Gbps mark in Jan. -

Broadband Impact Nunavut Screen-Based Industry

Scoping the Future of Broadband ’s Impact on Nunavut’s Screen-Based Industry Borealis Telecommunications Inc. BorealisTelecom.com March 31st, 2020 The future is already here - it is just not very evenly distributed - William Ford Gibson Table of Content EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 SECTION 1 – NUNAVUT’S BROADBAND CONTEXT 6 CURRENT STATE OF CONNECTIVITY 7 FUNDING PROGRAMS DILEMMA 8 TELESAT FLEET 9 SES FLEET 9 BACKGROUND HISTORY 10 DEVELOPING FACTORS 12 FUNDING INSTRUMENT ANNOUNCED IN THE 2019 FEDERAL BUDGET 13 ONGOING TELECOMMUNICATIONS PROJECTS 14 FIBRE BACKBONES 14 SATELLITE TECHNOLOGY 19 SECTION 2 - NUNAVUT-WIDE CAPACITY REQUIREMENT OUTLOOK 22 PREDICTIVE MODEL AND METHODOLOGY 22 PREDICTION MODEL ASSESSMENT VARIABLES 22 BANDWIDTH NEEDS PER COMMUNITY 26 NUNAVUT WIDE TOTAL BANDWIDTH REQUIREMENTS 2017 26 ADJUSTING THE NUMBERS FOR 2020 AND UP 28 POPULATION GROWTH 29 BANDWIDTH GROWTH 29 SECTION 3 – BROADBAND PROGRAMS 33 CRTC BROADBAND FUND 33 INNOVATION, SCIENCE AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT (ISED) 35 CANADA INFRASTRUCTURE BANK 35 SECTION 4 – BACKBONE TECHNOLOGY DEPLOYMENT 37 SATELLITE 37 SATELLITE DEVELOPMENT COST 37 FIBRE BACKBONE 39 i CLOSEST FIBRE-OPTIC POINT OF PRESENCE 39 SECTION 5 – CONTENT DISTRIBUTION TECHNOLOGY 41 MARKET INDICATORS 42 VIEWERSHIP 42 REVENUES 43 MEDIA CONTENT 44 NUNAVUT’S SCREEN-BASED INDUSTRY 45 VIDEO FILES 45 CONNECTIVITY LIMITATIONS 46 PRODUCTION TIME IMPACT 46 PRE-PRODUCTION 47 PRODUCTION 47 POST-PRODUCTION 47 TRAINING AND MENTORSHIP 48 DEVELOPING INUIT TV 49 STREAMING ON-DEMAND PLATFORM 50 INUIT TV STREAMING SERVICE ROADMAP -

NWS SOW Doc Apr 2020

North Warning System (NWS) Office Statement Of Work (SOW) April 2020 SOW Main Table Of Contents SOW Section 1: SOW Section 1- Table of Contents Sub Section 1 - NWS Concept of Operations (CONOPS); . Operational Authority (Comd 1 CAD) - Operational Direction and Guidance OUT . NWS CONCEPT OF OPERATION & MAINTENANCE Sub Section 2- NWS Program Management (PM) . NWS Project Management . Customer And Third Party Support . Ancillary Support . Significant Incidents . Technical Library and Document Management . Work Management System . Information Management Services and Information Technology Introduction . Security . Occupational health and Safety . NWS PM Position Requirements Sub Section 3- NWS Maintenance (Maint) and Sustainment (Sust) . Life Cycle Materiel Management And Life Cycle Facilities Management . Configuration Management . Sustainment Engineering . Project Management Services . Depot Level Support SOW Section 2: SOW Section 2 - Table of Contents Section 2 NWS Infrastructure . Introduction to Infrastructure SOW . 1- Maintenance Management and Engineering Services . 2- Facilities Maintenance Services . 3- Project Delivery Services . 4- Asset Management Plans, Facilities Condition Surveys and Building Condition Assessments . 5- Fire Protection Services . 6- Environmental Management Services . 7- Work Deliverables . 8- Service Delivery Regime and Acceptance Review Requirements . 9- Acceptance of the Real Property Service Delivery Regime SOW Section 3: SOW Section 3 – Table of Contents Sub Sec 1- Communications and Electronics (C&E) -

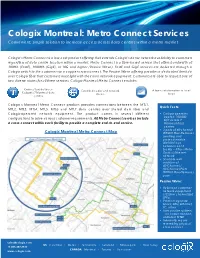

Cologix Montreal: Metro Connect Services Convenient, Simple Solution to Increase Access Across Data Centres Within a Metro Market

Cologix Montreal: Metro Connect Services Convenient, simple solution to increase access across data centres within a metro market Cologix’s Metro Connect is a low-cost product offering that extends Cologix’s dense network availability to customers regardless of data centre location within a market. Metro Connect is a fibre-based service that offers bandwidth of 100Mb (FastE), 1000Mb (GigE), or 10G and higher (Passive Wave). FastE and GigE services are delivered through a Cologix switch to the customer via a copper cross-connect. The Passive Wave offering provides a dedicated lambda over Cologix fibre that customers must light with their own network equipment. Customers are able to request one of two diverse routes for all three services. Cologix Montreal Metro Connect enables: Connections between Extended carrier and network A low-cost alternative to local Cologix’s 7 Montreal data choice loops centres Cologix’s Montreal Metro Connect product provides connections between the MTL1, Quick Facts: MTL2, MTL3, MTL4, MTL5, MTL6 and MTL7 data centres over shared dark fibre and Cologix-operated network equipment. The product comes in several different • Cologix operates confgurations to solve various customer requirements. All Metro Connect services include approx. 100,000 SQF across 7 a cross-connect within each facility to provide a complete end-to-end service. Montreal data centres • 2 pairs of 40-channel Cologix Montreal Metro Connect Map DWDM Mux-Demuxes (working and protect) enable 40x100 Gbps between each facility = 4Tbps Metro Optical -

The Distant Early Warning (DEW) Line: a Bibliography and Documentary Resource List

The Distant Early Warning (DEW) Line: A Bibliography and Documentary Resource List Prepared for the Arctic Institute of North America By: P. Whitney Lackenbauer, Ph.D. Matthew J. Farish, Ph.D. Jennifer Arthur-Lackenbauer, M.Sc. October 2005 © 2005 The Arctic Institute of North America ISBN 1-894788-01-X The DEW Line: Bibliography and Documentary Resource List 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 PREFACE 2 2.0 BACKGROUND DOCUMENTS 3 2.1 Exchange of Notes (May 5, 1955) Between Canada and the United States Of America Governing the Establishment of a Distant Early Warning System in Canadian Territory.......................................................................................................... 3 2.2 The DEW Line Story in Brief (Western Electric Corporation, c.1960) ……………… 9 2.3 List of DEW Line Sites ……………………………………….…………………….... 16 3.0 ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS 23 3.1 Rt. Hon. John George Diefenbaker Centre ……………………………………….…... 23 3.2 Library and Archives Canada …………………………………….…………………... 26 3.3 Department of National Defence, Directorate of History and Heritage ………………. 46 3.4 NWT Archives Council, Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre ……………….... 63 3.5 Yukon Territorial Archives, Whitehorse, YT ………………………………………… 79 3.6 Hudson Bay Company Archives ……………………………………………………... 88 3.7 Archives in the United States ……………………………………………………….… 89 4.0 PUBLISHED SOURCES 90 4.1 The Globe and Mail …………………………………………………………………………… 90 4.2 The Financial Post ………………………………………………………………………….…. 99 4.3 Other Print Media …………………………………………………………………..… 99 4.4 Contemporary Journal Articles ……………………………………………………..… 100 4.5 Government Publications …………………………………………………………….. 101 4.6 Corporate Histories ………………………………………………………………...... 103 4.7 Professional Journal Articles ………………………………………………………..… 104 4.8 Books ………………………………………………………………………………..… 106 4.9 Scholarly and Popular Articles ………………………………………………….……. 113 4.10 Environmental Issues and Cleanup: Technical Reports and Articles …………….…. 117 5.0 OTHER SOURCES 120 5.1 Theses and Dissertations ……………………………………………………………... -

Arctic Surveillance Civilian Commercial Aerial Surveillance Options for the Arctic

Arctic Surveillance Civilian Commercial Aerial Surveillance Options for the Arctic Dan Brookes DRDC Ottawa Derek F. Scott VP Airborne Maritime Surveillance Division Provincial Aerospace Ltd (PAL) Pip Rudkin UAV Operations Manager PAL Airborne Maritime Surveillance Division Provincial Aerospace Ltd Defence R&D Canada – Ottawa Technical Report DRDC Ottawa TR 2013-142 November 2013 Arctic Surveillance Civilian Commercial Aerial Surveillance Options for the Arctic Dan Brookes DRDC Ottawa Derek F. Scott VP Airborne Maritime Surveillance Division Provincial Aerospace Ltd (PAL) Pip Rudkin UAV Operations Manager PAL Airborne Maritime Surveillance Division Provincial Aerospace Ltd Defence R&D Canada – Ottawa Technical Report DRDC Ottawa TR 2013-142 November 2013 Principal Author Original signed by Dan Brookes Dan Brookes Defence Scienist Approved by Original signed by Caroline Wilcox Caroline Wilcox Head, Space and ISR Applications Section Approved for release by Original signed by Chris McMillan Chris McMillan Chair, Document Review Panel This work was originally sponsored by ARP project 11HI01-Options for Northern Surveillance, and completed under the Northern Watch TDP project 15EJ01 © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, as represented by the Minister of National Defence, 2013 © Sa Majesté la Reine (en droit du Canada), telle que représentée par le ministre de la Défense nationale, 2013 Preface This report grew out of a study that was originally commissioned by DRDC with Provincial Aerospace Ltd (PAL) in early 2007. With the assistance of PAL’s experience and expertise, the aim was to explore the feasibility, logistics and costs of providing surveillance and reconnaissance (SR) capabilities in the Arctic using private commercial sources. -

Download Speeds

Volume 08, September, 2017 A SAMENA Telecommunications Council Newsletter www.samenacouncil.org SAMENA TRENDS EXCLUSIVELY FOR SAMENA TELECOMMUNICATIONS COUNCIL'S MEMBERS BUILDING DIGITAL ECONOMIES Unleashing the Power of Digital Health 54 Building an Open and Diverse Ecosystem for Shared Success... 34 Exclusive Interview Eng. Saleh Al Abdooli Chief Executive Officer Etisalat Group DRIVING THE DIGITAL FUTURE VOLUME 08, SEPTEMBER, 2017 Contributing Editors Subscriptions Izhar Ahmad [email protected] Javaid Akhtar Malik Advertising SAMENA Contributing Members [email protected] Etisalat TRENDS Nokia SAMENA TRENDS Strategy& [email protected] Editor-in-Chief Tel: +971.4.364.2700 Bocar A. BA Publisher SAMENA Telecommunications Council CONTENTS 04 EDITORIAL 67 TECHNOLOGY UPDATES Technology News 18 REGIONAL & MEMBERS 78 REGULATORY & POLICY UPDATES Members News UPDATES Regulatory News Regional News A Snapshot of Regulatory Activities in the SAMENA 45 SATELLITE UPDATES Region Satellite News Regulatory Activities Beyond 58 WHOLESALE UPDATES the SAMENA Region The SAMENA TRENDS newsletter is Wholesale News wholly owned and operated by The SAMENA Telecommunications Council (SAMENA Council). Information in the newsletter is not intended as professional services advice, and SAMENA Council disclaims any liability for use of specific information or results thereof. Articles and information contained in this publication are the copyright of SAMENA Telecommunications Council, (unless otherwise noted, described or stated) and cannot be reproduced, copied or printed in any form without the express written permission of the publisher. The SAMENA Council does not necessari- 11 06 ly endorse, support, sanction, encourage, SAMENA COUNCIL ACTIVITY EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW verify or agree with the content, com- SAMENA Council Reflects on Public ments, opinions or statements made in Eng. -

Court File No. CV-16-11257-00CL ONTARIO SUPERIOR COURT of JUSTICE COMMERCIAL LIST

Court File No. CV-16-11257-00CL ONTARIO SUPERIOR COURT OF JUSTICE COMMERCIAL LIST IN THE MATTER OF THE COMPANIES’ CREDITORS ARRANGEMENT ACT, R.S.C. 1985, c. C-36, AS AMENDED AND IN THE MATTER OF A PLAN OF COMPROMISE OR ARRANGEMENT OF PT HOLDCO, INC., PRIMUS TELECOMMUNICATIONS CANADA, INC., PTUS, INC., PRIMUS TELECOMMUNICATIONS, INC., AND LINGO, INC. (Applicants) APPROVAL AND VESTING ORDER SERVICE LIST GENERAL STIKEMAN ELLIOTT LLP Samantha Horn 5300 Commerce Court West Tel: (416) 869- 5636 199 Bay Street Email: [email protected] Toronto, ON M5L 1B9 Maria Konyukhova Tel: (416) 869-5230 Email: [email protected] Kathryn Esaw Tel: (416) 869-6820 Email: [email protected] Vlad Calina Tel: (416) 869-5202 Lawyers for the Applicants Email: [email protected] FTI CONSULTING CANADA INC. Nigel D. Meakin TD Waterhouse Tower Tel: (416) 649-8100 79 Wellington Street, Suite 2010 Fax: (416) 649-8101 Toronto, ON M5K 1G8 Email: [email protected] Steven Bissell Tel: (416) 649-8100 Fax: (416) 649-8101 Email: [email protected] Kamran Hamidi Tel: (416) 649-8100 Fax: (416) 649-8101 Monitor Email: [email protected] 2 BLAKE, CASSELS & GRAYDON LLP Linc Rogers 199 Bay Street Tel: (416) 863-4168 Suite 4000, Commerce Court West Fax: (416) 863-2653 Toronto, ON M5L 1A9 Email: [email protected] Aryo Shalviri Tel: (416) 863- 2962 Fax: (416) 863-2653 Lawyers for the Monitor Email: [email protected] DAVIES WARD PHILLIPS VINEBERG LLP Natasha MacParland 155 Wellington Street West Tel: (416) 863 5567 Toronto, ON M5V 3J7 Fax: (416) 863 0871 Email: [email protected] Lawyers for the Bank of Montreal, as Administrative Agent for the Syndicate FOGLER, RUBINOFF LLP Gregg Azeff 77 King Street West Tel: (416) 365-3716 Suite 3000, P.O. -

Catalogue of Place Names in Northern East Greenland

Catalogue of place names in northern East Greenland In this section all officially approved, and many Greenlandic names are spelt according to the unapproved, names are listed, together with explana- modern Greenland orthography (spelling reform tions where known. Approved names are listed in 1973), with cross-references from the old-style normal type or bold type, whereas unapproved spelling still to be found on many published maps. names are always given in italics. Names of ships are Prospectors place names used only in confidential given in small CAPITALS. Individual name entries are company reports are not found in this volume. In listed in Danish alphabetical order, such that names general, only selected unapproved names introduced beginning with the Danish letters Æ, Ø and Å come by scientific or climbing expeditions are included. after Z. This means that Danish names beginning Incomplete documentation of climbing activities with Å or Aa (e.g. Aage Bertelsen Gletscher, Aage de by expeditions claiming ‘first ascents’ on Milne Land Lemos Dal, Åkerblom Ø, Ålborg Fjord etc) are found and in nunatak regions such as Dronning Louise towards the end of this catalogue. Å replaced aa in Land, has led to a decision to exclude them. Many Danish spelling for most purposes in 1948, but aa is recent expeditions to Dronning Louise Land, and commonly retained in personal names, and is option- other nunatak areas, have gained access to their al in some Danish town names (e.g. Ålborg or Aalborg region of interest using Twin Otter aircraft, such that are both correct). However, Greenlandic names be - the remaining ‘climb’ to the summits of some peaks ginning with aa following the spelling reform dating may be as little as a few hundred metres; this raises from 1973 (a long vowel sound rather than short) are the question of what constitutes an ‘ascent’? treated as two consecutive ‘a’s.