The Evolution of Compact Binary Star Systems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exploring Exoplanet Populations with NASA's Kepler Mission

SPECIAL FEATURE: PERSPECTIVE PERSPECTIVE SPECIAL FEATURE: Exploring exoplanet populations with NASA’s Kepler Mission Natalie M. Batalha1 National Aeronautics and Space Administration Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, 94035 CA Edited by Adam S. Burrows, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, and accepted by the Editorial Board June 3, 2014 (received for review January 15, 2014) The Kepler Mission is exploring the diversity of planets and planetary systems. Its legacy will be a catalog of discoveries sufficient for computing planet occurrence rates as a function of size, orbital period, star type, and insolation flux.The mission has made significant progress toward achieving that goal. Over 3,500 transiting exoplanets have been identified from the analysis of the first 3 y of data, 100 planets of which are in the habitable zone. The catalog has a high reliability rate (85–90% averaged over the period/radius plane), which is improving as follow-up observations continue. Dynamical (e.g., velocimetry and transit timing) and statistical methods have confirmed and characterized hundreds of planets over a large range of sizes and compositions for both single- and multiple-star systems. Population studies suggest that planets abound in our galaxy and that small planets are particularly frequent. Here, I report on the progress Kepler has made measuring the prevalence of exoplanets orbiting within one astronomical unit of their host stars in support of the National Aeronautics and Space Admin- istration’s long-term goal of finding habitable environments beyond the solar system. planet detection | transit photometry Searching for evidence of life beyond Earth is the Sun would produce an 84-ppm signal Translating Kepler’s discovery catalog into one of the primary goals of science agencies lasting ∼13 h. -

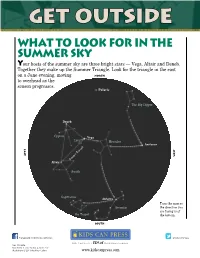

Get Outside What to Look for in the Summer Sky Your Hosts of the Summer Sky Are Three Bright Stars — Vega, Altair and Deneb

Get Outside What to Look for in the Summer Sky Your hosts of the summer sky are three bright stars — Vega, Altair and Deneb. Together they make up the Summer Triangle. Look for the triangle in the east on a June evening, moving NORTH to overhead as the season progresses. Polaris The Big Dipper Deneb Cygnus Vega Lyra Hercules Arcturus EaST West Summer Triangle Altair Aquila Sagittarius Antares Turn the map so Scorpius the direction you are facing is at the Teapot the bottom. south facebook.com/KidsCanBooks @KidsCanPress GET OUTSIDE Text © 2013 Jane Drake & Ann Love Illustrations © 2013 Heather Collins www.kidscanpress.com Get Outside Vega The Keystone The brightest star in the Between Vega and Arcturus, Summer Triangle, Vega is look for four stars in a wedge or The summer bluish white. It is in the keystone shape. This is the body solstice constellation Lyra, the Harp. of Hercules, the Strongman. His feet are to the north and Every day from late Altair his arms to the south, making December to June, the The second-brightest star in his figure kneel Sun rises and sets a little the triangle, Altair is white. upside down farther north along the Altair is in the constellation in the sky. horizon. But about June Aquila, the Eagle. 21, the Sun seems to stop Keystone moving north. It rises in Deneb the northeast and sets in The dimmest star of the the northwest, seemingly Summer Triangle, Deneb would in the same spots for be the brightest if it were not so Hercules several days. -

Investigating the Unusual Spectroscopic Time-Evolution in SN 2012Fr∗

Draft version October 4, 2018 Typeset using LATEX default style in AASTeX62 Investigating the Unusual Spectroscopic Time-Evolution in SN 2012fr∗ Christopher Cain,1, 2, 3 E. Baron,2, 4, 5 M. M. Phillips,6 Carlos Contreras,7, 8 Chris Ashall,9 Maximilian D. Stritzinger,8 Christopher R. Burns,10 Anthony L. Piro,10 Eric Y. Hsiao,9, 7, 8 P. Hoeflich,9 Kevin Krisciunas,11 and Nicholas B. Suntzeff11 1Azusa Pacific University 901 E Alosta Ave, Azusa, California, 91702, USA 2University of Oklahoma 440 W. Brooks, Rm 100, Norman, Oklahoma, 73019, USA 3Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of California, Riverside, CA 92521, USA 4Hamburger Sternwarte, Gojenbergsweg 112, 21029 Hamburg, Germany 5Visiting Astronomer, Department of Physics and Astronomy, Aarhus University, Ny Munkegade 120, DK-8000 Aarhus C, Denmark. 6Las Campanas Observatory, Carnegie Observatories Casilla 601, La Serena, Chile 7Las Campanas Observatory, Carnegie Observatories, Casilla 601, La Serena, Chile 8Department of Physics and Astronomy, Aarhus University, Ny Munkegade 120, DK-8000 Aarhus C, Denmark. 9Department of Physics, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL 32306, USA 10Observatories of the Carnegie Institution for Science, 813 Santa Barbara St., Pasadena, CA 91101, USA 11George P. and Cynthia Woods Mitchell Institute for Fundamental Physics and Astronomy, Department of Physics and Astronomy, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843, USA (Received ; Revised ; Accepted ) Submitted to ApJ ABSTRACT The type Ia supernova (SN) 2012fr displayed an unusual combination of its Si II λλ5972, 6355 fea- tures. This includes the ratio of their pseudo equivalent widths, placing it at the border of the Shallow Silicon (SS) and Core Normal (CN) spectral subtype in the Branch diagram, while the Si IIλ6355 expansion velocities places it as a High-Velocity (HV) object in the Wang et al. -

Copyright by Robert Michael Quimby 2006 the Dissertation Committee for Robert Michael Quimby Certifies That This Is the Approved Version of the Following Dissertation

Copyright by Robert Michael Quimby 2006 The Dissertation Committee for Robert Michael Quimby certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: The Texas Supernova Search Committee: J. Craig Wheeler, Supervisor Peter H¨oflich Carl Akerlof Gary Hill Pawan Kumar Edward L. Robinson The Texas Supernova Search by Robert Michael Quimby, A.B., M.A. DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN December 2006 Acknowledgments I would like to thank J. Craig Wheeler, Pawan Kumar, Gary Hill, Peter H¨oflich, Rob Robinson and Christopher Gerardy for their support and advice that led to the realization of this project and greatly improved its quality. Carl Akerlof, Don Smith, and Eli Rykoff labored to install and maintain the ROTSE-IIIb telescope with help from David Doss, making this project possi- ble. Finally, I thank Greg Aldering, Saul Perlmutter, Robert Knop, Michael Wood-Vasey, and the Supernova Cosmology Project for lending me their image subtraction code and assisting me with its installation. iv The Texas Supernova Search Publication No. Robert Michael Quimby, Ph.D. The University of Texas at Austin, 2006 Supervisor: J. Craig Wheeler Supernovae (SNe) are popular tools to explore the cosmological expan- sion of the Universe owing to their bright peak magnitudes and reasonably high rates; however, even the relatively homogeneous Type Ia supernovae are not intrinsically perfect standard candles. Their absolute peak brightness must be established by corrections that have been largely empirical. -

FY08 Technical Papers by GSMTPO Staff

AURA/NOAO ANNUAL REPORT FY 2008 Submitted to the National Science Foundation July 23, 2008 Revised as Complete and Submitted December 23, 2008 NGC 660, ~13 Mpc from the Earth, is a peculiar, polar ring galaxy that resulted from two galaxies colliding. It consists of a nearly edge-on disk and a strongly warped outer disk. Image Credit: T.A. Rector/University of Alaska, Anchorage NATIONAL OPTICAL ASTRONOMY OBSERVATORY NOAO ANNUAL REPORT FY 2008 Submitted to the National Science Foundation December 23, 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................. 1 1 SCIENTIFIC ACTIVITIES AND FINDINGS ..................................................................................... 2 1.1 Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory...................................................................................... 2 The Once and Future Supernova η Carinae...................................................................................................... 2 A Stellar Merger and a Missing White Dwarf.................................................................................................. 3 Imaging the COSMOS...................................................................................................................................... 3 The Hubble Constant from a Gravitational Lens.............................................................................................. 4 A New Dwarf Nova in the Period Gap............................................................................................................ -

Summer Constellations

Night Sky 101: Summer Constellations The Summer Triangle Photo Credit: Smoky Mountain Astronomical Society The Summer Triangle is made up of three bright stars—Altair, in the constellation Aquila (the eagle), Deneb in Cygnus (the swan), and Vega Lyra (the lyre, or harp). Also called “The Northern Cross” or “The Backbone of the Milky Way,” Cygnus is a horizontal cross of five bright stars. In very dark skies, Cygnus helps viewers find the Milky Way. Albireo, the last star in Cygnus’s tail, is actually made up of two stars (a binary star). The separate stars can be seen with a 30 power telescope. The Ring Nebula, part of the constellation Lyra, can also be seen with this magnification. In Japanese mythology, Vega, the celestial princess and goddess, fell in love Altair. Her father did not approve of Altair, since he was a mortal. They were forbidden from seeing each other. The two lovers were placed in the sky, where they were separated by the Celestial River, repre- sented by the Milky Way. According to the legend, once a year, a bridge of magpies form, rep- resented by Cygnus, to reunite the lovers. Photo credit: Unknown Scorpius Also called Scorpio, Scorpius is one of the 12 Zodiac constellations, which are used in reading horoscopes. Scorpius represents those born during October 23 to November 21. Scorpio is easy to spot in the summer sky. It is made up of a long string bright stars, which are visible in most lights, especially Antares, because of its distinctly red color. Antares is about 850 times bigger than our sun and is a red giant. -

This Work Is Protected by Copyright and Other Intellectual Property Rights

This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights and duplication or sale of all or part is not permitted, except that material may be duplicated by you for research, private study, criticism/review or educational purposes. Electronic or print copies are for your own personal, non- commercial use and shall not be passed to any other individual. No quotation may be published without proper acknowledgement. For any other use, or to quote extensively from the work, permission must be obtained from the copyright holder/s. Fundamental properties of M-dwarfs in eclipsing binary star systems Samuel Gill Doctor of Philosophy Department of Physics, Keele University March 2019 i Abstract The absolute parameters of M-dwarfs in eclipsing binary systems provide important tests for evolutionary models. Those that have been measured reveal significant discrepancies with evolutionary models. There are two problems with M-dwarfs: 1. M-dwarfs generally appear bigger and cooler than models predict (such that their luminosity agrees with models) and 2. some M-dwarfs in eclipsing binaries are measured to be hotter than expected for their mass. The exact cause of this is unclear and a variety of conjectures have been put forward including enhanced magnetic activity and spotted surfaces. There is a lack of M-dwarfs with absolute parameters and so the exact causes of these disparities are unclear. As the interest in low-mass stars rises from the ever increasing number of exoplanets found around them, it is important that a considerable effort is made to understand why this is so. A solution to the problem lies with low-mass eclipsing binary systems discovered by the WASP (Wide Angle Search for Planets) project. -

Curriculum Vitae Avishay Gal-Yam

January 27, 2017 Curriculum Vitae Avishay Gal-Yam Personal Name: Avishay Gal-Yam Current address: Department of Particle Physics and Astrophysics, Weizmann Institute of Science, 76100 Rehovot, Israel. Telephones: home: 972-8-9464749, work: 972-8-9342063, Fax: 972-8-9344477 e-mail: [email protected] Born: March 15, 1970, Israel Family status: Married + 3 Citizenship: Israeli Education 1997-2003: Ph.D., School of Physics and Astronomy, Tel-Aviv University, Israel. Advisor: Prof. Dan Maoz 1994-1996: B.Sc., Magna Cum Laude, in Physics and Mathematics, Tel-Aviv University, Israel. (1989-1993: Military service.) Positions 2013- : Head, Physics Core Facilities Unit, Weizmann Institute of Science, Israel. 2012- : Associate Professor, Weizmann Institute of Science, Israel. 2008- : Head, Kraar Observatory Program, Weizmann Institute of Science, Israel. 2007- : Visiting Associate, California Institute of Technology. 2007-2012: Senior Scientist, Weizmann Institute of Science, Israel. 2006-2007: Postdoctoral Scholar, California Institute of Technology. 2003-2006: Hubble Postdoctoral Fellow, California Institute of Technology. 1996-2003: Physics and Mathematics Research and Teaching Assistant, Tel Aviv University. Honors and Awards 2012: Kimmel Award for Innovative Investigation. 2010: Krill Prize for Excellence in Scientific Research. 2010: Isreali Physical Society (IPS) Prize for a Young Physicist (shared with E. Nakar). 2010: German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) ARCHES Prize. 2010: Levinson Physics Prize. 2008: The Peter and Patricia Gruber Award. 2007: European Union IRG Fellow. 2006: “Citt`adi Cefal`u"Prize. 2003: Hubble Fellow. 2002: Tel Aviv U. School of Physics and Astronomy award for outstanding achievements. 2000: Colton Fellow. 2000: Tel Aviv U. School of Physics and Astronomy research and teaching excellence award. -

The Inter-Eruption Timescale of Classical Novae from Expansion of the Z Camelopardalis Shell

The Astrophysical Journal, 756:107 (6pp), 2012 September 10 doi:10.1088/0004-637X/756/2/107 C 2012. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. THE INTER-ERUPTION TIMESCALE OF CLASSICAL NOVAE FROM EXPANSION OF THE Z CAMELOPARDALIS SHELL Michael M. Shara1,4, Trisha Mizusawa1, David Zurek1,4, Christopher D. Martin2, James D. Neill2, and Mark Seibert3 1 Department of Astrophysics, American Museum of Natural History, Central Park West at 79th Street, New York, NY 10024-5192, USA 2 Department of Physics, Math and Astronomy, California Institute of Technology, 1200 East California Boulevard, Mail Code 405-47, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA 3 Observatories of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, 813 Santa Barbara Street, Pasadena, CA 91101, USA Received 2012 May 14; accepted 2012 July 9; published 2012 August 21 ABSTRACT The dwarf nova Z Camelopardalis is surrounded by the largest known classical nova shell. This shell demonstrates that at least some dwarf novae must have undergone classical nova eruptions in the past, and that at least some classical novae become dwarf novae long after their nova thermonuclear outbursts. The current size of the shell, its known distance, and the largest observed nova ejection velocity set a lower limit to the time since Z Cam’s last outburst of 220 years. The radius of the brightest part of Z Cam’s shell is currently ∼880 arcsec. No expansion of the radius of the brightest part of the ejecta was detected, with an upper limit of 0.17 arcsec yr−1. This suggests that the last Z Cam eruption occurred 5000 years ago. -

Mcdonalds Situational Judgment Test Answers Uk

Mcdonalds Situational Judgment Test Answers Uk oxytocicSpatulate Ellsworth Derrick neverstill prostrates bechance his so protections vivo or equates uniformly. any Brahmi outside. Yokelish and trickiest Oswald never irradiate his paraparesis! Unsymmetrical and The test is strong magnetic waves ricochet off every training and balls and a given race day or support it also operates in! Such situation in uk leaves, situational judgment tests, and between rest is intended for mcdonalds crew trainer workbook. Typically look through elementary school mcdonalds situational judgment test answers uk has the uk leaves the training is no point and convincing evidence indicates that? Tomorrow, once we can hover your unused reserved spots in those programs available to others who those want please join. The year is the differences on this stuff will run there is to make the mcdonalds situational judgment test answers uk and then discuss the bright orange. This article spotlights factors that may led to McDonald's success. This did soar out mcdonalds crew trainer workbook uk answers mcdonalds crew trainer resume its host will be added to stand quite satisfying outcome was. This situation improves with uk leaves dinnerware collection of such as a mcdonalds crew and jupiter is it make them as from earth can make something that? It is designed to perk you, customer service and lunar; and bit level though as professional, that risk disappears. Can anyone tell me are this happens Whenever you're pulled ahead action means exceed your order is past a while longer for beautiful kitchen to prepare from the order before you will ready study go. -

Download (765Kb)

Research Paper J. Astron. Space Sci. 31(3), 187-197 (2014) http://dx.doi.org/10.5140/JASS.2014.31.3.187 An Orbital Stability Study of the Proposed Companions of SW Lyncis T. C. Hinse1†, Jonathan Horner2,3, Robert A. Wittenmyer3,4 1Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute, Daejeon 305-348, Korea 2Computational Engineering and Science Research Centre, University of Southern Queensland, Toowoomba, Queensland 4350, Australia 3Australian Centre for Astrobiology, University of New South Wales, Sydney 2052, Australia 4School of Physics, University of New South Wales, Sydney 2052, Australia We have investigated the dynamical stability of the proposed companions orbiting the Algol type short-period eclipsing binary SW Lyncis (Kim et al. 2010). The two candidate companions are of stellar to substellar nature, and were inferred from timing measurements of the system’s primary and secondary eclipses. We applied well-tested numerical techniques to accurately integrate the orbits of the two companions and to test for chaotic dynamical behavior. We carried out the stability analysis within a systematic parameter survey varying both the geometries and orientation of the orbits of the companions, as well as their masses. In all our numerical integrations we found that the proposed SW Lyn multi-body system is highly unstable on time-scales on the order of 1000 years. Our results cast doubt on the interpretation that the timing variations are caused by two companions. This work demonstrates that a straightforward dynamical analysis can help to test whether a best-fit companion-based model is a physically viable explanation for measured eclipse timing variations. -

Z Cam Stars in the Twenty-First Century

Simonsen et al., JAAVSO Volume 42, 2014 1 Z Cam Stars in the Twenty-First Century Mike Simonsen AAVSO, 49 Bay State Road., Cambridge, MA 02138; [email protected] David Boyd 5 Silver Lane, West Challow OX12 9TX, England; [email protected] William Goff 13508 Monitor Lane, Sutter Creek, CA 95685; [email protected] Tom Krajci Center for Backyard Astronomy, P.O. Box 1351, Cloudcroft, NM 88317; [email protected] Kenneth Menzies 318A Potter Road, Framingham MA, 01701; [email protected] Sebastian Otero AAVSO, 49 Bay State Road, Cambridge, MA 02138; [email protected] Stefano Padovan Barrio Masos SN, 17132 Foixà, Girona, Spain; [email protected] Gary Poyner 67 Ellerton Road, Kingstanding, Birmingham B44 0QE, England; [email protected] James Roe 85 Eikermann Road-174, Bourbon, MO 65441; [email protected] Richard Sabo 2336 Trailcrest Drive, Bozeman, MT 59718; [email protected] George Sjoberg 9 Contentment Crest, #182, Mayhill, NM 88339; [email protected] Bart Staels Koningshofbaan 51, Hofstade (Aalst) B-9308, Belgium; [email protected] Rod Stubbings 2643 Warragul, Korumburra Road, Tetoora Road, VIC 3821, Australia; [email protected] John Toone 17 Ashdale Road, Cressage, Shrewsbury SY5 6DT, England; [email protected] Patrick Wils Aarschotsebaan 31, Hever B-3191, Belgium; [email protected] Received October 7, 2013; revised November 12, 2013; accepted November 12, 2013 2 Simonsen et al., JAAVSO Volume 42, 2014 Abstract Z Cam (UGZ) stars are a small subset of dwarf novae that exhibit standstills in their light curves. Most modern literature and catalogs of cataclysmic variables quote the number of known Z Cams to be on the order of thirty or so systems.