Black Narcissus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, a MATTER of LIFE and DEATH/ STAIRWAY to HEAVEN (1946, 104 Min)

December 8 (XXXI:15) Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, A MATTER OF LIFE AND DEATH/ STAIRWAY TO HEAVEN (1946, 104 min) (The version of this handout on the website has color images and hot urls.) Written, Produced and Directed by Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger Music by Allan Gray Cinematography by Jack Cardiff Film Edited by Reginald Mills Camera Operator...Geoffrey Unsworth David Niven…Peter Carter Kim Hunter…June Robert Coote…Bob Kathleen Byron…An Angel Richard Attenborough…An English Pilot Bonar Colleano…An American Pilot Joan Maude…Chief Recorder Marius Goring…Conductor 71 Roger Livesey…Doctor Reeves Robert Atkins…The Vicar Bob Roberts…Dr. Gaertler Hour of Glory (1949), The Red Shoes (1948), Black Narcissus Edwin Max…Dr. Mc.Ewen (1947), A Matter of Life and Death (1946), 'I Know Where I'm Betty Potter…Mrs. Tucker Going!' (1945), A Canterbury Tale (1944), The Life and Death of Abraham Sofaer…The Judge Colonel Blimp (1943), One of Our Aircraft Is Missing (1942), 49th Raymond Massey…Abraham Farlan Parallel (1941), The Thief of Bagdad (1940), Blackout (1940), The Robert Arden…GI Playing Bottom Lion Has Wings (1939), The Edge of the World (1937), Someday Robert Beatty…US Crewman (1935), Something Always Happens (1934), C.O.D. (1932), Hotel Tommy Duggan…Patrick Aloyusius Mahoney Splendide (1932) and My Friend the King (1932). Erik…Spaniel John Longden…Narrator of introduction Emeric Pressburger (b. December 5, 1902 in Miskolc, Austria- Hungary [now Hungary] —d. February 5, 1988, age 85, in Michael Powell (b. September 30, 1905 in Kent, England—d. Saxstead, Suffolk, England) won the 1943 Oscar for Best Writing, February 19, 1990, age 84, in Gloucestershire, England) was Original Story for 49th Parallel (1941) and was nominated the nominated with Emeric Pressburger for an Oscar in 1943 for Best same year for the Best Screenplay for One of Our Aircraft Is Writing, Original Screenplay for One of Our Aircraft Is Missing Missing (1942) which he shared with Michael Powell and 49th (1942). -

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy in the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger 1939-1946 Valerie Wilson University College London PhD May 2001 ProQuest Number: U642581 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest U642581 Published by ProQuest LLC(2015). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946 This thesis will examine the films planned or made by Powell and Pressburger in this period, with these aims: to demonstrate the way the contemporary realities of wartime Britain (political, social, cultural, economic) are represented in these films, and how the realities of British history (together with information supplied by the Ministry of Information and other government ministries) form the basis of much of their propaganda. to chart the changes in the stylistic combination of realism, naturalism, expressionism and surrealism, to show that all of these films are neither purely realist nor seamless products of artifice but carefully constructed narratives which use fantasy genres (spy stories, rural myths, futuristic utopias, dreams and hallucinations) to convey their message. -

Modus Operandi Films and High Point Media Group Present

Modus Operandi Films and High Point Media Group Present A film by Craig McCall Worldwide Sales: High Point Media Group Contact in Cannes: Residences du Grand Hotel, Cormoran II, 3 rd Floor: Tel: +33 (0) 4 93 38 05 87 London Contact: Tel: +44 20 7424 6870. Fax +44 20 7435 3281 [email protected] CAMERAMAN: The Life & Work of Jack Cardiff page 1 of 27 © Modus Operandi Films 2010 HP PRESS KIT CAMERAMAN: The Life and Work of Jack Cardiff www.jackcardiff.com Contents: - Film Synopsis p 3 - 10 Facts About Jack p 4 - Jack Cardiff Filmography p 5 - Quotes about Jack p 6 - Director’s Notes p 7 - Interviewee’s p 8 - Bio’s of Key Crew p10 - Director's Q&A p14 - Credits p 19 CAMERAMAN: The Life & Work of Jack Cardiff page 2 of 27 © Modus Operandi Films 2010 HP PRESS KIT CAMERAMAN : The Life and Work of Jack Cardiff A Documentary Feature Film Logline: Celebrating the remarkable nine decade career of legendary cinematographer, Jack Cardiff, who provided the canvas for classics like The Red Shoes and The African Queen . Short Synopsis: Jack Cardiff’s career spanned an incredible nine of moving picture’s first ten decades and his work behind the camera altered the look of films forever through his use of Technicolor photography. Craig McCall’s passionate film about the legendary cinematographer reveals a unique figure in British and international cinema. Long Synopsis: Cameraman illuminates a unique figure in British and international cinema, Jack Cardiff, a man whose life and career are inextricably interwoven with the history of cinema spanning nine decades of moving pictures' ten. -

Boxoffice Barometer (March 6, 1961)

MARCH 6, 1961 IN TWO SECTIONS SECTION TWO Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents William Wyler’s production of “BEN-HUR” starring CHARLTON HESTON • JACK HAWKINS • Haya Harareet • Stephen Boyd • Hugh Griffith • Martha Scott • with Cathy O’Donnell • Sam Jaffe • Screen Play by Karl Tunberg • Music by Miklos Rozsa • Produced by Sam Zimbalist. M-G-M . EVEN GREATER IN Continuing its success story with current and coming attractions like these! ...and this is only the beginning! "GO NAKED IN THE WORLD” c ( 'KSX'i "THE Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents GINA LOLLOBRIGIDA • ANTHONY FRANCIOSA • ERNEST BORGNINE in An Areola Production “GO SPINSTER” • • — Metrocolor) NAKED IN THE WORLD” with Luana Patten Will Kuluva Philip Ober ( CinemaScope John Kellogg • Nancy R. Pollock • Tracey Roberts • Screen Play by Ranald Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer pre- MacDougall • Based on the Book by Tom T. Chamales • Directed by sents SHIRLEY MacLAINE Ranald MacDougall • Produced by Aaron Rosenberg. LAURENCE HARVEY JACK HAWKINS in A Julian Blaustein Production “SPINSTER" with Nobu McCarthy • Screen Play by Ben Maddow • Based on the Novel by Sylvia Ashton- Warner • Directed by Charles Walters. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents David O. Selznick's Production of Margaret Mitchell’s Story of the Old South "GONE WITH THE WIND” starring CLARK GABLE • VIVIEN LEIGH • LESLIE HOWARD • OLIVIA deHAVILLAND • A Selznick International Picture • Screen Play by Sidney Howard • Music by Max Steiner Directed by Victor Fleming Technicolor ’) "GORGO ( Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents “GORGO” star- ring Bill Travers • William Sylvester • Vincent "THE SECRET PARTNER” Winter • Bruce Seton • Joseph O'Conor • Martin Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents STEWART GRANGER Benson • Barry Keegan • Dervis Ward • Christopher HAYA HARAREET in “THE SECRET PARTNER” with Rhodes • Screen Play by John Loring and Daniel Bernard Lee • Screen Play by David Pursall and Jack Seddon Hyatt • Directed by Eugene Lourie • Executive Directed by Basil Dearden • Produced by Michael Relph. -

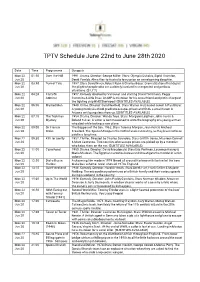

TPTV Schedule June 22Nd to June 28Th 2020

TPTV Schedule June 22nd to June 28th 2020 Date Time Programme Synopsis Mon 22 01:50 Over The Hill 1991. Drama. Director: George Miller. Stars: Olympia Dukakis, Sigrid Thornton, Jun 20 Derek Fowlds. Alma flies to Australia to surprise an unwelcoming daughter. Mon 22 03:50 Turn of Fate 1957. Stars David Niven, Robert Ryan & Charles Boyer. Dramatizations that depict Jun 20 the plight of people who are suddenly involved in unexpected and perilous situations. (S1, E7) Mon 22 04:20 Carry On 1957. Comedy directed by Val Guest and starring David Tomlinson, Peggy Jun 20 Admiral Cummins & Alfie Bass. An MP is mistaken for his naval friend and put in charge of the fighting ship HMS Sherwood! (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 22 06:00 Marked Men 1940. Crime. Director: Sam Newfield. Stars Warren Hull, Isabel Jewell & Paul Bryar. Jun 20 A young medical-school graduate escapes prison and finds a small haven in Arizona until gangsters show up. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 22 07:10 The Teckman 1954. Drama. Director: Wendy Toye. Stars: Margaret Leighton, John Justin & Jun 20 Mystery Roland Culver. A writer is commissioned to write the biography of a young airman who died while testing a new plane. Mon 22 09:00 Sir Francis The Beggars of the Sea. 1962. Stars Terence Morgan, Jean Kent & Michael Jun 20 Drake Crawford. The Spanish troops in the Netherlands ear mutiny, as they have not been paid in a long time. Mon 22 09:30 Kill Her Gently 1957. Thriller. Directed by Charles Saunders. Stars Griffith Jones, Maureen Connell Jun 20 & Marc Lawrence. -

Two Day Autograph Auction Day 1 Saturday 02 November 2013 11:00

Two Day Autograph Auction Day 1 Saturday 02 November 2013 11:00 International Autograph Auctions (IAA) Office address Foxhall Business Centre Foxhall Road NG7 6LH International Autograph Auctions (IAA) (Two Day Autograph Auction Day 1 ) Catalogue - Downloaded from UKAuctioneers.com Lot: 1 tennis players of the 1970s TENNIS: An excellent collection including each Wimbledon Men's of 31 signed postcard Singles Champion of the decade. photographs by various tennis VG to EX All of the signatures players of the 1970s including were obtained in person by the Billie Jean King (Wimbledon vendor's brother who regularly Champion 1966, 1967, 1968, attended the Wimbledon 1972, 1973 & 1975), Ann Jones Championships during the 1970s. (Wimbledon Champion 1969), Estimate: £200.00 - £300.00 Evonne Goolagong (Wimbledon Champion 1971 & 1980), Chris Evert (Wimbledon Champion Lot: 2 1974, 1976 & 1981), Virginia TILDEN WILLIAM: (1893-1953) Wade (Wimbledon Champion American Tennis Player, 1977), John Newcombe Wimbledon Champion 1920, (Wimbledon Champion 1967, 1921 & 1930. A.L.S., Bill, one 1970 & 1971), Stan Smith page, slim 4to, Memphis, (Wimbledon Champion 1972), Tennessee, n.d. (11th June Jan Kodes (Wimbledon 1948?), to his protégé Arthur Champion 1973), Jimmy Connors Anderson ('Dearest Stinky'), on (Wimbledon Champion 1974 & the attractive printed stationery of 1982), Arthur Ashe (Wimbledon the Hotel Peabody. Tilden sends Champion 1975), Bjorn Borg his friend a cheque (no longer (Wimbledon Champion 1976, present) 'to cover your 1977, 1978, 1979 & 1980), reservation & ticket to Boston Francoise Durr (Wimbledon from Chicago' and provides Finalist 1965, 1968, 1970, 1972, details of the hotel and where to 1973 & 1975), Olga Morozova meet in Boston, concluding (Wimbledon Finalist 1974), 'Crazy to see you'. -

Feature Films

Libraries FEATURE FILMS The Media and Reserve Library, located in the lower level of the west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 0.5mm DVD-8746 2012 DVD-4759 10 Things I Hate About You DVD-0812 21 Grams DVD-8358 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse DVD-0048 21 Up South Africa DVD-3691 10th Victim DVD-5591 24 Hour Party People DVD-8359 12 DVD-1200 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-2780 Discs 12 and Holding DVD-5110 25th Hour DVD-2291 12 Angry Men DVD-0850 25th Hour c.2 DVD-2291 c.2 12 Monkeys DVD-8358 25th Hour c.3 DVD-2291 c.3 DVD-3375 27 Dresses DVD-8204 12 Years a Slave DVD-7691 28 Days Later DVD-4333 13 Going on 30 DVD-8704 28 Days Later c.2 DVD-4333 c.2 1776 DVD-0397 28 Days Later c.3 DVD-4333 c.3 1900 DVD-4443 28 Weeks Later c.2 DVD-4805 c.2 1984 (Hurt) DVD-6795 3 Days of the Condor DVD-8360 DVD-4640 3 Women DVD-4850 1984 (O'Brien) DVD-6971 3 Worlds of Gulliver DVD-4239 2 Autumns, 3 Summers DVD-7930 3:10 to Yuma DVD-4340 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her DVD-6091 30 Days of Night DVD-4812 20 Million Miles to Earth DVD-3608 300 DVD-9078 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea DVD-8356 DVD-6064 2001: A Space Odyssey DVD-8357 300: Rise of the Empire DVD-9092 DVD-0260 35 Shots of Rum DVD-4729 2010: The Year We Make Contact DVD-3418 36th Chamber of Shaolin DVD-9181 1/25/2018 39 Steps DVD-0337 About Last Night DVD-0928 39 Steps c.2 DVD-0337 c.2 Abraham (Bible Collection) DVD-0602 4 Films by Virgil Wildrich DVD-8361 Absence of Malice DVD-8243 -

Babel Film Festival 2019 Anna Karina, Il Volto

_ n.3 Anno IX N. 79 | Gennaio 2020 | ISSN 2431 - 6739 Politiche educative e formazione culturale Anna Karina, il volto iconico passato e futuro cinematografica per i giovani in Germania della Nouvelle Vague Danimarca 1940 – Parigi 14 Dicembre 2019 Il cinema educa alla in programma dall'8 di questo mese al 1° mar- vita! zo prossimo. Se n'è andata il 14 dicembre, die- Dopo una visita a fine Novembre a Francoforte ci giorni dopo l'inaugurazione dell'atelier (ben sul Meno di una delegazione di Diari di Cine- successivo alle loro comuni imprese in cop- club, la responsabile delle attività di alfabetiz- pia) di Godard, "Le Studio d'Orphée" alla Fon- zazione del dipartimento di educazione cine- dazione Prada. Aveva appena fatto in tempo matografica del DDF - DeutschesFilminstitut & Bergamo a volerla come ospite d'onore e sog- Filmmuseum, Christine Kopf interviene per getto presente e parlante della propria retro- raccontare la storia e le politiche culturali dell’i- spettiva nella scorsa edizione, come Cannes a stituto di cinema tedesco dedicarle il manifesto e Bologna a... cineritro- varla l'anno precedente. A oltre sessant'anni Nei 124 anni della sua esi- dalla sua esplosione, la nouvelle vague si sta pro- stenza, il cinema ha subi- gressivamente quanto inesorabilmente conge- to cambiamenti incredi- dando. Nella tragedia, col suicidio di Jean Se- bili. Già dalle sfarfallanti berg (1979); nel dramma, con le scomparse brevi sequenze delle pri- premature di Truffaut (‘84) e Demy ('90); per me immagini, quelle che naturale uscita dalla vita, come nei casi di sono state lanciate da Chabrol e Rohmer (2010), più di recente di Ri- proiettori rumorosi sugli Non è riuscita a vedere e a farsi vedere, come vette (2016), Jeanne Moreau (2017) e Agnés schermi di sale fieristi- si attendeva e ci si augurava, alla retrospettiva Varda pochi mesi or sono. -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) House of Preposterous Women: Michelle Williams Gamaker Re-Auditions Kanchi Lord, C.; Williams Gamaker, M. Publication date 2019 Document Version Final published version Published in OAR: The Oxford Artistic and Practice Based Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Lord, C., & Williams Gamaker, M. (2019). House of Preposterous Women: Michelle Williams Gamaker Re-Auditions Kanchi. OAR: The Oxford Artistic and Practice Based, 3, 9-17. https://www.oarplatform.com/house-of-preposterous-women-michelle-williams-gamaker-re- auditions-kanchi/ General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:02 Oct 2021 House of Preposterous Women: Michelle Williams Gamaker re-auditions Kanchi Catherine Lord with Michelle Williams Gamaker To cite this contribution: Lord, Catherine, with Michelle Williams Gamaker. -

Liminal Soundscapes in Powell & Pressburger's Wartime Films

Liminal soundscapes in Powell & Pressburger’s wartime films Anita Jorge To cite this version: Anita Jorge. Liminal soundscapes in Powell & Pressburger’s wartime films. Studies in European Cinema, Intellect, 2016, 14 (1), pp.22 - 32. 10.1080/17411548.2016.1248531. hal-01699401 HAL Id: hal-01699401 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01699401 Submitted on 8 Feb 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Liminal soundscapes in Powell & Pressburger’s wartime films Anita Jorge Université de Lorraine This article explores Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger’s wartime films through the prism of the soundscape, focusing on the liminal function of sound. Dwelling on such films as 49th Parallel (1941) and One of Our Aircraft is Missing (1942), it argues that sound acts as a diegetic tool translating the action into a spatiotemporal elsewhere, as well as a liberation tool, enabling the people threatened by Nazi assimilation to reach for a more permissive world where restrictions no longer operate. Lastly, the soundscape serves as a ‘translanguage’, bridging the gap between soldiers and civilians, or between different nations fighting against a common enemy, thus giving birth to a transnational community. -

Shoot the Messenger

Shoot the Messenger Dir: Ngozi Onwurah, UK, 2006 A review by Stephen Harper, University of Portsmouth, UK The BBC drama Shoot the Messenger (BBC2, 30 August, 2006) is a provocative exploration of racial politics within London's African Caribbean community. Originally entitled Fuck Black People!, the film provoked strong criticism, not least from the pressure group Ligali. The drama was written by Sharon Foster, best known as the writer of Babyfather, who won the Dennis Potter Screenwriting Award for her screenplay. David Oyelowo plays Joe Pascale, a well-meaning middle class schoolteacher whose efforts to 'make a difference' in the education of failing black pupils in an inner-city school result in unemployment, schizophrenia and homelessness. The tribulations of the idealistic teacher are hardly new in British television drama: Jimmy McGovern's 1995 series Hearts and Minds is one noteworthy example. But Shoot the Messenger's central concern with race orients it specifically towards contemporary debates around multiculturalism and social exclusion such as that prompted by the Parekh Report (2000). The concern with black educational failure is key within these debates. A DfES report 'Getting it. Getting it right' (2007) noted that Black Caribbean students in Britain are excluded from school far more often than white pupils. Although BBC television drama has addressed these issues in recent years in productions such as Lennie James' Storm Damage (BBC2, 2000), Shoot the Messenger nonetheless carries a heavy representational burden. For several years the lack of racial diversity in BBC programmes has been criticised (Creeber, 2004) and concerns about the BBC's treatment of its visible minority staff abound (see, for example, "BBC still showing its 'hideously white' face," 2002). -

British Film Institute Report & Financial Statements 2006

British Film Institute Report & Financial Statements 2006 BECAUSE FILMS INSPIRE... WONDER There’s more to discover about film and television British Film Institute through the BFI. Our world-renowned archive, cinemas, festivals, films, publications and learning Report & Financial resources are here to inspire you. Statements 2006 Contents The mission about the BFI 3 Great expectations Governors’ report 5 Out of the past Archive strategy 7 Walkabout Cultural programme 9 Modern times Director’s report 17 The commitments key aims for 2005/06 19 Performance Financial report 23 Guys and dolls how the BFI is governed 29 Last orders Auditors’ report 37 The full monty appendices 57 The mission ABOUT THE BFI The BFI (British Film Institute) was established in 1933 to promote greater understanding, appreciation and access to fi lm and television culture in Britain. In 1983 The Institute was incorporated by Royal Charter, a copy of which is available on request. Our mission is ‘to champion moving image culture in all its richness and diversity, across the UK, for the benefi t of as wide an audience as possible, to create and encourage debate.’ SUMMARY OF ROYAL CHARTER OBJECTIVES: > To establish, care for and develop collections refl ecting the moving image history and heritage of the United Kingdom; > To encourage the development of the art of fi lm, television and the moving image throughout the United Kingdom; > To promote the use of fi lm and television culture as a record of contemporary life and manners; > To promote access to and appreciation of the widest possible range of British and world cinema; and > To promote education about fi lm, television and the moving image generally, and their impact on society.