A Bachelor's World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ORANGE COUNTY CAUFORNIA Continued on Page 53

KENNEDY KLUES Research Bulletin VOLUME II NUMBER 2 & 3 · November 1976 & February 1977 Published by:. Mrs • Betty L. Pennington 6059 Emery Street Riverside, California 92509 i . SUBSCRIPTION RATE: $6. oo per year (4 issues) Yearly Index Inc~uded $1. 75 Sample copy or back issues. All subscriptions begin with current issue. · $7. 50 per year (4 issues) outside Continental · · United States . Published: · August - November - Febr:UarY . - May .· QUERIES: FREE to subscribers, no restrictions as· ·to length or number. Non subscribers may send queries at the rate of 10¢ pe~)ine, .. excluding name and address. EDITORIAL POLICY: -The E.ditor does· not assume.. a~y responsibility ~or error .. of fact bR opinion expressed by the. contributors. It is our desire . and intent to publish only reliable genealogical sour~e material which relate to the name of KENNEDY, including var.iants! KENEDY, KENNADY I KENNEDAY·, KENNADAY I CANADA, .CANADAY' · CANADY,· CANNADA and any other variants of the surname. WHEN YOU MOVE: Let me know your new address as soon as possibie. Due. to high postal rates, THIS IS A MUST I KENNEDY KLyES returned to me, will not be forwarded until a 50¢ service charge has been paid, . coi~ or stamps. BOOK REVIEWS: Any biographical, genealogical or historical book or quarterly (need not be KENNEDY material) DONATED to KENNEDY KLUES will be reviewed in the surname· bulletins·, FISHER FACTS, KE NNEDY KLUES and SMITH SAGAS • . Such donations should be marked SAMfLE REVIEW COPY. This is a form of free 'advertising for the authors/ compilers of such ' publications~ . CONTRIBUTIONS:· Anyone who has material on any KE NNEDY anywhere, anytime, is invited to contribute the material to our putilication. -

American Visionary: John F. Kennedy's Life and Times

American Visionary: John F. Kennedy’s Life and Times Organized by Wiener Schiller Productions in collaboration with the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library Curated by Lawrence Schiller Project Coordinator: Susan Bloom All images are 11 x 14 inches All frames are 17 x 20 inches 1.1 The Making of JFK John “Jack” Fitzgerald Kennedy at Nantasket Beach, Massachusetts, circa 1918. Photographer unknown (Corbis/Getty Images) The still-growing Kennedy family spent summers in Hull, Massachusetts on the Boston Harbor up to the mid-1920s, before establishing the family compound in Hyannis Port. 1.2 The Making of JFK A young Jack in the ocean, his father nearby, early 1920s. Photographer Unknown (John F. Kennedy Library Foundation) Kennedy’s young life was punctuated with bouts of illness, but he was seen by his teachers as a tenacious boy who played hard. He developed a great love of reading early, with a special interest in British and European history. 1.3 The Making of JFK Joseph Kennedy with sons Jack (left) and Joseph Patrick Jr., Brookline, Massachusetts, 1919. Photographer Unknown (John F. Kennedy Library Foundation) In 1919 Joe Kennedy began his career as stockbroker, following a position as bank president which he assumed in 1913 at age twenty-five. By 1935, his wealth had grown to $180 million; the equivalent to just over $3 billion today. Page 1 Updated 3/7/17 1.4 The Making of JFK The Kennedy children, June, 1926. Photographer Unknown (John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum) Left to right: Joe Jr., Jack, Rose Marie, Kathleen, and Eunice, taken the year Joe Kennedy Sr. -

{PDF EPUB} the Peter Lawford Story Life with the Kennedys Monroe and the Rat Pack by Patricia Lawford Stewart the Tragic History of the Rat Pack

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} The Peter Lawford Story Life with the Kennedys Monroe and the Rat Pack by Patricia Lawford Stewart The Tragic History Of The Rat Pack. The Rat Pack is the epitome of Mad Men- style old-school cool. As Colin Bertram of Biography tells us, the legendary group of entertainers were originally acquaintances who used to hang around at Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall's home in Los Angeles. Before their most famous line- up, they had a Who's Who list of satellite members that included David Niven, Spencer Tracy, and Robert Mitchum. They were by no means a "men only" club, either: Early on, legendary ladies such as Ava Gardner, Judy Garland, Elizabeth Taylor and Audrey Hepburn counted themselves in the group's ranks. In fact, the Rat Pack didn't even really want to be one. They actually liked to be called "The Summit" or "The Clan." Still, regardless of their full list of members or original naming aspirations, history has come to know the group as the Rat Pack, and Frank Sinatra, Sammy Davis Jr., Dean Martin, Peter Lawford, and Joey Bishop are considered its core members. As effortlessly awesome as the group appeared to be, there was actually a lot of turmoil and sadness behind the scenes. Today, we'll take a look at the tragic history of the Rat Pack. Peter Lawford's right hand. If you're hard-pressed to name an iconic Peter Lawford movie, you probably won't be alone. Though his IMDb page shows that his acting career was lengthy and impressive, his entry on the Hollywood Walk of Fame website tells us that Lawford also had a couple of other things playing in his favor. -

National US History Bee Round #8

National US History Bee Round 8 1. This book was the first to examine the separation of spheres of men and women. The author of this book traces the title concept back to the Puritan Founding. The author of this book was accompanied on his trip by Gustave de Beaumont and toured various prisons in the United States before writing it. What classic tome was written by Alexis de Tocqueville? ANSWER: On Democracy in America [or De la démocratie en Amérique] 066-13-92-08101 2. This family had a female member who married actor Peter Lawford and another female member who married Sargent Shriver and founded the Special Olympics. This family lost one member when he was killed by Sirhan Sirhan and another member was involved in the Chappaquiddick scandal. What is this family of Attorney General Robert and Massachusetts Senator Teddy? ANSWER: Kennedy 052-13-92-08102 3. This offensive was motivated by an image of the Dignity Battalions attacking Billy Ford with a metal pipe. Guillermo Endera was secretly sworn in prior to this initiative, in which rock music was blasted as part of Operation Nifty Package. It was code-named Operation Just Cause, and it ousted Manuel Noriega. What 1989 invasion did the US carry out in a Central American country with a canal? ANSWER: US invasion of Panama [or Operation Just Cause prior to mention; accept just Panama after "invasion" is read] 020-13-92-08103 4. This industry was tarnished by the drug-fueled death of Eddie Guerrero and murders committed by Chris Benoit. -

Marilyn Monroe's 'Mr. X': Was He Robert Kennedy?

SFExaitie: (A) OCT 2 7 177 Marilyn Monroe's 'Mr. X': Was He Robert Kennedy? NEW YORK — (UPI) — A veteran Broadway- Hollywood columnist says Robert F. Kennedy was the "Mr. X" in Marilyn Monroe's life — a friend whom she saw repeatedly during the months preceding her tragic death. In a new book Earl Wilson says that what may have been Mari- lyn's last words were spoken over the tele- phone to actor Peter Lawford, a brother- in-law of the Kennedys with whom they often ROBERT F. KENNEDY MARILYN MONROE PETER LAWFORD stayed on visits to the Was he Mr. X? "Slurred voice" Worried over condition coast. Fred Lawrence Guiles, whose "Norma planes, going the Palm "They both visited the away. Let me get in Jean" may be the defin- Springs - Vegas - Lake Lawfords at their beach touch with her lawyer or Tahoe route. But one did house," the columnist itive biography of Mari- doctor.' " Wilson re- lyn, said without naming not say these things says. "Marilyn Monroe, ports. about the Kennedys in who was in the circle of Psychiatrist Called names that she had a se- print." the Lawfords' friends, cret lover, and that he Ebbins got hold of Mil- was in Los Angeles the Wilson notes that also visited them at the Guiles' book says Mari- beach house." ton "Mickey" Rudin, night she died there. lyn courted privacy dur- Marilyn's attorney, who Wilson, whose column On Aug. 4, 1962, Wil- called Dr. Ralph Green- appears in The Examin- ing her last summer son says, Lawford invit- "because she was in- son, a Beverly Hills psy- er, does not make this ed Marilyn a n d her chiatrist who had been volved with a married press agent, Pat(rioia) claim. -

Movie Time Descriptive Video Service

DO NOT DISCARD THIS CATALOG. All titles may not be available at this time. Check the Illinois catalog under the subject “Descriptive Videos or DVD” for an updated list. This catalog is available in large print, e-mail and braille. If you need a different format, please let us know. Illinois State Library Talking Book & Braille Service 300 S. Second Street Springfield, IL 62701 217-782-9260 or 800-665-5576, ext. 1 (in Illinois) Illinois Talking Book Outreach Center 125 Tower Drive Burr Ridge, IL 60527 800-426-0709 A service of the Illinois State Library Talking Book & Braille Service and Illinois Talking Book Centers Jesse White • Secretary of State and State Librarian DESCRIPTIVE VIDEO SERVICE Borrow blockbuster movies from the Illinois Talking Book Centers! These movies are especially for the enjoyment of people who are blind or visually impaired. The movies carefully describe the visual elements of a movie — action, characters, locations, costumes and sets — without interfering with the movie’s dialogue or sound effects, so you can follow all the action! To enjoy these movies and hear the descriptions, all you need is a regular VCR or DVD player and a television! Listings beginning with the letters DV play on a VHS videocassette recorder (VCR). Listings beginning with the letters DVD play on a DVD Player. Mail in the order form in the back of this catalog or call your local Talking Book Center to request movies today. Guidelines 1. To borrow a video you must be a registered Talking Book patron. 2. You may borrow one or two videos at a time and put others on your request list. -

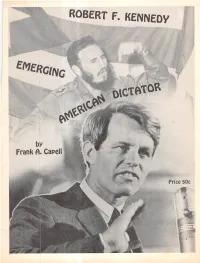

Robert F. Kennedy

ROBERT F. KENNEDY '.4?i V / by Frank A. CapeK Price 50c / * • 1 K* Copyright 1968 by FRANK A. CAPELL All Rights Reserved Published by the Herald of Freedc m Zarephath, New Jersey 08890 ABOUT THE AUTHOR Frank A. Capell is the editor ofThe HERALD ofFREEDON , a national anti-communist educational bi-weekly. Beginning as an undercover criminal nv(5siigator(tight-roper)for dis- trict attorneys and police commissioners, he later became Chi 5f| Investigator of the West- Chester County (N.Y.) Sheriffs Office. In this capacity he ejsta )lished a Bureau of Subver- sive Activities. He supervised the investigation of over five t 4sand individuals and organ- izations, including Nazis, Fascists and Communists, on behallf c the F.B.I, in many cases. During World War II, he served as a civilian investigator ovjerstak doing intelligence work. The author has been fighting the enemies of our country for twenty-nine years in of- ficial and unofficial capacities. As a writer, lecturer, instrucior researcher and investigator, he has appeared before audiences and on radio and television fiioni c^astto coast. Hemaintains files containing the names of almost two million people who liiaye aided the International Communist Conspiracy. Mr. Capell is the author of "Freedc m [sj Up To You" (now out of print), "The Threat From Within," "Treason is the Reason," "T le Strange Death of Marilyn Monroe," and "The Strange Case of Jacob Javits." His biogjrap tiy has appeared for many years in "Who's Who in Commerce and Industry." INTRODUCTION The knights of Camelot are on the march again On this occasion Kennedy was reported as stat since Prince Bobby has announced he will make his ing: move to restore the Kennedy Dynasty in 1968 in "We should INTENSIFY DISARMAMENTEFFORTS stead of 1972. -

Oral History Interview – JFK#1, 12/17/1965 Administrative Information

Robert E. Thompson Oral History Interview – JFK#1, 12/17/1965 Administrative Information Creator: Robert E. Thompson Interviewer: Ronald J. Grele Date of Interview: December 17, 1965 Length: 35 pages (Please note: There is no page 18) Biographical Note Thompson, journalist. Press Secretary, John F. Kennedy's Massachusetts senatorial reelection campaign (1958); Washington correspondent, Los Angeles Times (1962-1966) author, Robert F. Kennedy: The Brother Within (1962), discusses his contributions the 1958 campaign as Press Secretary and coverage of JFK’s presidential campaign and time in the White House, among other issues. Access Open Usage Restrictions According to the deed of gift signed October 31, 1973, copyright of these materials has been assigned to the United States Government. Users of these materials are advised to determine the copyright status of any document from which they wish to publish. Users of these materials are advised to determine the copyright status of any document from which they wish to publish. Copyright The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excesses of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. -

Jill Cowan and Priscilla Wear, Oral History Interview – 03/16/1965 Administrative Information

Jill Cowan and Priscilla Wear, Oral History Interview – 03/16/1965 Administrative Information Creator: Jill Cowan and Priscilla Wear Interviewer: William J. vanden Heuvel Date of Interview: March 16, 1965 Length: 29 pages Biographical Note Cowan was a staff member in the Office of the White House Press Secretary under Pierre E. G. Salinger; Wear was a staff member under President John F. Kennedy’s [JFK] secretary, Evelyn N. Lincoln. In this interview they discuss their article in Look magazine; personal recollections of President JFK’s assassination; working on JFK’s 1960 presidential campaign; JFK’s campaigning style; JFK’s relationship with the press, White House staff, and his family; and JFK’s trips to Nassau, Europe, and Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson’s ranch, among other issues. Access Open. Usage Restrictions According to the deed of gift signed April 14, 2009, copyright of these materials has been retained by the donor. Users of these materials are advised to determine the copyright status of any document from which they wish to publish. Copyright The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excesses of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. -

Ted Kennedy 3

Kouin Galvin The Matter Of TheKennedy C CTER Gary Allen is author of None Dare Call It Conspiracy; The Rockefeller File; Kissinger: Secret Side Of The Secretary Of State; Jimmy Carter/Jimmy Carter; and, Tax Target: Washington. He is an AMERICAN OPINION Contributing Editor. • HUMORIST Tom Anderson has hold his head up . That's true enough. quipped that an article on Teddy What we intend to deal with here is Kennedy's character would have to be how Edward Moore Kennedy got the one of the shortest literary pieces in way he is. history. As far as Anderson is con The last time that the private life cerned, Kennedy has no character, pe of a Presidential candidate was a ma riod. After Chappaquiddick, when jor campaign issue was in 1884, when Teddy showed up at Mary Jo Kopech Grover Cleveland's illegitimate child ne's funeral wearing a neck brace, was the subject of great controversy. Tom remarked that he needed it to Since that time there has been a sort JANUARY, 1980 1 Then there are the important character im plications. Can a man who consistently lies to his own wife be trusted not to lie to the country? Similarly, does compulsive adultery reveal an unstable and self-destructive personality? If so, what are the chances that it will effect his judgment and reactions in a time of crisis? of gentleman's agreement among pol late whether more people have be iticians and the press that the subject trayed their country over sex or love not be discussed. Frankly, the general than out of greed for money. -

Sydney Maleia Kennedy Lawford

Sydney maleia kennedy lawford Continue Patricia Kennedy Lawford Personal Information Birth name Patricia Helen Kennedy LawfordBirthy May 6, 1924 Brooklyn, Massachusetts, USA Fallification September 17, 2006 (82 years) New York, United StatesKaus of death PneumoniaAN NationalityR chose Catholicism FamilyPads Joseph. Kennedy and Rose FitzgeraldConuation Peter Lawford Succinct Christopher, Sidney, Victoria and Robin IsabelFamilars John F. Kennedy, Robert F. Kennedy and Ted Kennedy-Educated Education at Rosemont College Professional Information Trial Lawford (May 6, 1924 -September 17, 2006) - American socialite, six of Joseph's nine children. Kennedy and Rose Fitzgerald, sister of President John F. Kennedy and Senators Robert F. Kennedy and Ted Kennedy. His father's business project at RKO Radio Pictures influenced his interest in Hollywood. After graduating from Rosemont College, she moved there in hopes of becoming a producer and director, like her father, although as a woman in the 1950s she was only eligible for production assistant on kate Smith's radio show and then at the family theater of Peyton's father and the Rosary family crusade. She met British actor Peter Lawford through her sister Eunice in the 1940s and met repeatedly until 1953, when Lawford gagged her and formally announced her marriage in February 1954. They married on April 24, 1954, at St. Thomas More Catholic Church in New York City, two weeks before their 30th birthday. They settled in Santa Monica, California, and often communicated with actress Judy Garland and her family. With Peter's entry into the Rat Pack, his relationship gradually deteriorated. After Peter's sentimental shreds and alcohol problems, shortly after the assassination of John F. -

John F. “Frankie” Riegel January 23, 1949-December 19, 1967

Arlington National Cemetery Arlington National Cemetery consists of 624 acres. There is an average of 27-30 funerals each day Monday-Friday and six to eight funerals on Saturday. There are now more than 400,000 active duty service members, veterans and their families buried at Arlington. This image is courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. John F. “Frankie” Riegel January 23, 1949-December 19, 1967 Frankie Riegel, also known as “Spanky,” far left in this picture, was born in Arlington, Virginia, but grew up in the Gettysburg area. His father died when he was very young. He attended the Hoffman Home and Gettysburg High School. Before enlisting in the Marines, he worked at Howe’s Sunoco, 61 Buford Avenue, Gettysburg, now the site of Tom Knox Auto Service. This image was taken in September, 1967, three months before his death in Vietnam. This image is courtesy of Fred Permenter. John F. “Frankie” Riegel January 23, 1949-December 19, 1967 Frankie Riegel, served along the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) in Vietnam. He enlisted in 1966 and arrived in Vietnam in July, 1967 and saw a lot of combat. “Spanky always complained about being point.” He was first wounded by shrapnel in the left leg on September 10, 1967. On December 12, 1967 he was wounded again with the tip of his right thumb shot off. One week later he was part of a five man patrol that was ambushed in Quang Nam. Three of the five men died, including Riegel, after he was shot in the chest. He is listed on Panel 32E, Row 27 on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial.