Rapping Gender and Violence? Addressing Violence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Williams, Hipness, Hybridity, and Neo-Bohemian Hip-Hop

HIPNESS, HYBRIDITY, AND “NEO-BOHEMIAN” HIP-HOP: RETHINKING EXISTENCE IN THE AFRICAN DIASPORA A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Maxwell Lewis Williams August 2020 © 2020 Maxwell Lewis Williams HIPNESS, HYBRIDITY, AND “NEO-BOHEMIAN” HIP-HOP: RETHINKING EXISTENCE IN THE AFRICAN DIASPORA Maxwell Lewis Williams Cornell University 2020 This dissertation theorizes a contemporary hip-hop genre that I call “neo-bohemian,” typified by rapper Kendrick Lamar and his collective, Black Hippy. I argue that, by reclaiming the origins of hipness as a set of hybridizing Black cultural responses to the experience of modernity, neo- bohemian rappers imagine and live out liberating ways of being beyond the West’s objectification and dehumanization of Blackness. In turn, I situate neo-bohemian hip-hop within a history of Black musical expression in the United States, Senegal, Mali, and South Africa to locate an “aesthetics of existence” in the African diaspora. By centering this aesthetics as a unifying component of these musical practices, I challenge top-down models of essential diasporic interconnection. Instead, I present diaspora as emerging primarily through comparable responses to experiences of paradigmatic racial violence, through which to imagine radical alternatives to our anti-Black global society. Overall, by rethinking the heuristic value of hipness as a musical and lived Black aesthetic, the project develops an innovative method for connecting the aesthetic and the social in music studies and Black studies, while offering original historical and musicological insights into Black metaphysics and studies of the African diaspora. -

Ashanti Ja Rule Dating

Ashanti joins HuffPost Live to discuss her relationship with rapper Ja Rule. Subscribe to The Morning Email. Wake up to the day's most important news. CONVERSATIONS. Today is National Voter Registration Day! We made it easy for you to exercise your right to vote! Register Now! News;. Jan 27, · Ja Rule’s Girlfriend. Ja Rule is single. He is not dating anyone currently. Ja had at least 4 relationship in the past. Ja Rule has not been previously engaged. He has three children, Brittney, Jeffrey and Jordan, with his wife Aisha Murray Atkins, who he married in April According to our records, he has 3 renuzap.podarokideal.ruality: American. May 19, · Longtime collaborators, Ja Rule and Ashanti, have been linked together in romance rumors for the last two decades and, given their amazing musical chemistry, some fans assumed it . May 19, · Dispute the rumors over the past years, Ashanti is denying that she ever dated Ja Rule. The princess of R&B, Ashanti, jumped on Instagram live with Fat Joe and revealed that the two never shared a romantic relationship. As we know, Ashanti and Ja have been linked together for the past two decades, and collectively put out numerous amount of hits. May 18, · From there Ashanti was a household name, often performing with her friend and label-mate, rapper JaRule. The singer and rapper collaborated on numerous songs like, “Always On Time” and Ja Rule is often rapping or acting as a hypeman on her songs. Mar 07, · Ashanti joins HuffPost Live to discuss her relationship with rapper Ja Rule. -

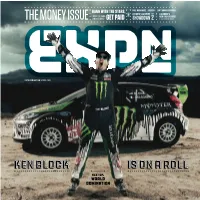

KEN BLOCK Is on a Roll Is on a Roll Ken Block

PAUL RODRIGUEZ / FRENDS / LYN-Z ADAMS HAWKINS HANG WITH THE STARS, PART lus OLYMPIC HALFPIPE A SLEDDER’S (TRAVIS PASTRANA, P NEW ENERGY DRINK THE MONEY ISSUE JAMES STEWART) GET PAID SHOWDOWN 2 IT’S A SHOCKER! PAGE 8 ESPN.COM/ACTION SPRING 2010 KENKEN BLOCKBLOCK IS ON A RROLLoll NEXT UP: WORLD DOMINATION SPRING 2010 X SPOT 14 THE FAST LIFE 30 PAY? CHECK. Ken Block revolutionized the sneaker Don’t have the board skills to pay the 6 MAJOR GRIND game. Is the DC Shoes exec-turned- bills? You can make an action living Clint Walker and Pat Duffy race car driver about to take over the anyway, like these four tradesmen. rally world, too? 8 ENERGIZE ME BY ALYSSA ROENIGK 34 3BR, 2BA, SHREDDABLE POOL Garth Kaufman Yes, foreclosed properties are bad for NOW ON ESPN.COM/ACTION 9 FLIP THE SCRIPT 20 MOVE AND SHAKE the neighborhood. But they’re rare gems SPRING GEAR GUIDE Brady Dollarhide Big air meets big business! These for resourceful BMXer Dean Dickinson. ’Tis the season for bikinis, boards and bikes. action stars have side hustles that BY CARMEN RENEE THOMPSON 10 FOR LOVE OR THE GAME Elena Hight, Greg Bretz and Louie Vito are about to blow. FMX GOES GLOBAL 36 ON THE FLY: DARIA WERBOWY Freestyle moto was born in the U.S., but riders now want to rule MAKE-OUT LIST 26 HIGHER LEARNING The supermodel shreds deep powder, the world. Harley Clifford and Freeskier Grete Eliassen hits the books hangs with Shaun White and mentors Lyn-Z Adams Hawkins BOBBY BROWN’S BIG BREAK as hard as she charges on the slopes. -

The Symbolic Annihilation of the Black Woman in Rap Videos: a Content Analysis

The Symbolic Annihilation of the Black Woman in Rap Videos: A Content Analysis Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Manriquez, Candace Lynn Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 28/09/2021 03:10:19 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/624121 THE SYMBOLIC ANNIHILATION OF THE BLACK WOMAN IN RAP VIDEOS: A CONTENT ANALYSIS by Candace L. Manriquez ____________________________ Copyright © Candace L. Manriquez 2017 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNICATION In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2017 Running head: THE SYMBOLIC ANNIHILATION OF THE BLACK WOMAN 2 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR The thesis titled The Symbolic Annihilation of the Black Woman: A Content Analysis prepared by Candace Manriquez has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for a master’s degree at the University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that an accurate acknowledgement of the source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his or her judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. -

Eminem Interview Download

Eminem interview download LINK TO DOWNLOAD UPDATE 9/14 - PART 4 OUT NOW. Eminem sat down with Sway for an exclusive interview for his tenth studio album, Kamikaze. Stream/download Kamikaze HERE.. Part 4. Download eminem-interview mp3 – Lost In London (Hosted By DJ Exclusive) of Eminem - renuzap.podarokideal.ru Eminem X-Posed: The Interview Song Download- Listen Eminem X-Posed: The Interview MP3 song online free. Play Eminem X-Posed: The Interview album song MP3 by Eminem and download Eminem X-Posed: The Interview song on renuzap.podarokideal.ru 19 rows · Eminem Interview Title: date: source: Eminem, Back Issues (Cover Story) Interview: . 09/05/ · Lil Wayne has officially launched his own radio show on Apple’s Beats 1 channel. On Friday’s (May 8) episode of Young Money Radio, Tunechi and Eminem Author: VIBE Staff. 07/12/ · EMINEM: It was about having the right to stand up to oppression. I mean, that’s exactly what the people in the military and the people who have given their lives for this country have fought for—for everybody to have a voice and to protest injustices and speak out against shit that’s wrong. Eminem interview with BBC Radio 1 () Eminem interview with MTV () NY Rock interview with Eminem - "It's lonely at the top" () Spin Magazine interview with Eminem - "Chocolate on the inside" () Brian McCollum interview with Eminem - "Fame leaves sour aftertaste" () Eminem Interview with Music - "Oh Yes, It's Shady's Night. Eminem will host a three-hour-long special, “Music To Be Quarantined By”, Apr 28th Eminem StockX Collab To Benefit COVID Solidarity Response Fund. -

King of Crunk Lil Jon Sets Guinness World Record™ for “Biggest Bling”

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE PRESS CONTACT Simone Smalls Susan Blond, Inc. 212-333-7728 x118 [email protected] KING OF CRUNK LIL JON SETS GUINNESS WORLD RECORD™ FOR “BIGGEST BLING” Rapper Makes History for His ‘Crunk Ain’t Dead’ Pendant New York, NY – (March 22, 2007) – TVT Records / BME recording artist Lil Jon is not only the King of Crunk, but he is now the King of Bling! Lil Jon just set a new Guinness World Record for the ‘Largest Diamond Pendant’ for his ‘Crunk Aint Dead’ pendant. With an appraised value of $500,000, Lil Jon’s diamond pendant is 7.5 inches tall, 6 inches wide, and 1 inch thick, weighing 5.11 pounds with a total 73 carats of diamonds. The total stone count is 3,756 genuine round-cut white diamonds set in 18-karat yellow and white gold. The piece was created by jeweler Jason of Beverly Hills. “I’m glad the Guinness World Records folks acknowledged me and my Crunk Ain’t Dead piece,” says Lil Jon. “I spent a load of money on that chain. I had no idea I would break a record and be recognized for it. It’s an honor to be included on that list. I grew up on reading and hearing about people and celebrities who break records in the Guinness World Records Book and it always fascinated me. Now that I’m on the list, it feels great. Let’s just see how many rappers try to outdo my pendant and break my record. They don’t call me the King of Crunk for nothing!” “Guinness World Records is pleased to recognize Lil Jon as a new member of our record- breaking family,” said Alistair Richards, Guinness World Records Managing Director. -

The Portrayal of African American Women in Hip-Hop Videos

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 6-2005 The Portrayal of African American Women in Hip-Hop Videos Ladel Lewis Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Lewis, Ladel, "The Portrayal of African American Women in Hip-Hop Videos" (2005). Master's Theses. 4192. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/4192 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PORTRAYAL OF AFRICAN AMERICAN WOMEN IN HIP-HOP VIDEOS By Ladel Lewis A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Sociology Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan June 2005 Copyright by Ladel Lewis 2005 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thankmy advisor, Dr. Zoann Snyder, forthe guidance and the patience she has rendered. Although she had a course reduction forthe Spring 2005 semester, and incurred some minor setbacks, she put in overtime in assisting me get my thesis finished. I appreciate the immediate feedback, interest and sincere dedication to my project. You are the best Dr. Snyder! I would also like to thank my committee members, Dr. Douglas Davison, Dr. Charles Crawford and honorary committee member Dr. David Hartman fortheir insightful suggestions. They always lent me an ear, whether it was fora new joke or about anything. -

Ft"3Bliriiat $T;0O

ft"3bliriiaT $T;0O On a political level, LIBERA deals with the STAFF FOR THIS ISSUE: Ned Asta, contemporary woman as she joins with others in an Susan Stern, Dianna (loodwin, Lynda effort to effect a change upon her condition. Koolish, Marion Sircfman, Cathy Drey fuss, Emotionally, it explores the root level of our feelings, Janet Phe la n, Jo Ann Wash) burn, Jana Harris, those beyond the ambitions and purposes women have traditionally been conditioned to embrace. One AnfTMize and Suzanne l.oomis of our objectives is to provide a medium for the new Published by LIBERA with the sponsorship of the woman to present herself without inhibition or Associated Students of the University of California affectation. By illuminating not only women's (Berkeley) and the Berkeley Women's Collective. Sub- political and intellectual achievements, but also her scription rates: $3 for 3 issues. $1.25 per copy for fantasies, dreams, art, the dark side of her face, we issue number 1. $1 per copy for following issues. come to know more her depths, and redefine ourselves. This publication on file at the International Women's\ History Archive, 2325 Oak St., Berkeley CA. 94708. V WOMEN: We need your contributions of articles, poetry, prose, humor, drawings and photographs (black and white). If you'd like your work returned, please send a stamped, self-addressed envelope. We also welcome any interested women to join the LIBERA collective. \: 516 Eshleman Hall U. of California Berkeley, California no. 3 winter 1973 94720 (415) 642-6673 TABLE OF CONTENTS ARTICLES Jeff Desmond's Letter 3 Vietnam: A Feminist Analysis Lesbian Feminists 14 Unequal Opportunity and the Chicana Linda Peralta Aquilar 32 - Femal Heterosexuality: Its Causes and Cures Joan Hand 38 POETRY a letter to sisters in the women's movement Lynda Koolish 3 POEM FOR MY FATHER Janet Phelan 4 to my mother Susan Stern 11 LITTLE POEMS FOR SLEEPING WITH YOU Sharon Barba 13 Ben Lomond, Ca. -

Legal Writing, the Remix: Plagiarism and Hip Hop Ethics

Mercer Law Review Volume 63 Number 2 Articles Edition Article 4 3-2012 Legal Writing, the Remix: Plagiarism and Hip Hop Ethics Kim D. Chanbonpin Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.mercer.edu/jour_mlr Part of the Cultural Heritage Law Commons, and the Legal Writing and Research Commons Recommended Citation Chanbonpin, Kim D. (2012) "Legal Writing, the Remix: Plagiarism and Hip Hop Ethics," Mercer Law Review: Vol. 63 : No. 2 , Article 4. Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.mercer.edu/jour_mlr/vol63/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Mercer Law School Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mercer Law Review by an authorized editor of Mercer Law School Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Legal Writing, the Remix: Plagiarism and Hip Hop Ethics by Kim D. Chanbonpin I. PRELUDE I begin this Article with a necessary caveat. Although I place hip hop music and culture at the center of my discussion about plagiarism and legal writing pedagogy, and my aim here is to uncover ways in which hip hop can be used as a teaching tool, I cannot claim to be a hip hop head.' A hip hop "head" is a devotee of the music, an acolyte of its discourse, and, oftentimes, an evangelist spreading the messages contained therein.2 One head, the MC' (or emcee) KRS-One,4 uses religious * Assistant Professor of Law, The John Marshall Law School (Chicago). University of California, Berkeley (B.A., 1999); University of Hawaii (J.D., 2003); Georgetown University Law Center (LL.M., 2006). -

P22 Layout 1

22 Established 1961 Tuesday, June 4, 2019 Lifestyle Gossip he Strokes and Charli XCX’s Governors Ball with the likes of SOB X RBE and Soccer Mommy - wasn’t fans affected by the cancellation, which means customers T sets were cancelled due to thunderstorms. The able to play. However, the 26-year-old star treated her with Sunday day tickets will get all their money back, severe weather forecast meant the final day of fans to a last minute performance at Le Poisson Rouge, while those with a three-day weekend pass will likely get a the festival in New York was postponed until and the intimate club show immediately sold out after the third back. In a statement, the festival reps said: “After 6.30pm local time on Sunday, and although music did announcement on Twitter. Charli wrote: “My Gov Ball per- close consultation with NYC officials and law enforce- eventually get under way, the storms hit the site and the formance got cancelled due to potential storms so I’m put- ment, it was deemed necessary to evacuate the site and event was cancelled at around 9.30pm with punters told to ting on a last minute show tonight in Manhattan.” When a cancel the Sunday evening of Gov Ball 2019 for the safety leave immediately by the nearest exits. It meant the ‘Late fan suggested the event - which cost $15 a ticket - should of our festival goers, artists, and crew. The safety of every- Nite’ hitmakers weren’t able to perform, while fellow have been free to Governor Ball punters, the musician one always comes first.” headliner SZA also couldn’t play her set at the top of the agreed but said it couldn’t be done. -

Music 6581 Songs, 16.4 Days, 30.64 GB

Music 6581 songs, 16.4 days, 30.64 GB Name Time Album Artist Rockin' Into the Night 4:00 .38 Special: Anthology .38 Special Caught Up In You 4:37 .38 Special: Anthology .38 Special Hold on Loosely 4:40 Wild-Eyed Southern Boys .38 Special Voices Carry 4:21 I Love Rock & Roll (Hits Of The 80's Vol. 4) 'Til Tuesday Gossip Folks (Fatboy Slimt Radio Mix) 3:32 T686 (03-28-2003) (Elliott, Missy) Pimp 4:13 Urban 15 (Fifty Cent) Life Goes On 4:32 (w/out) 2 PAC Bye Bye Bye 3:20 No Strings Attached *NSYNC You Tell Me Your Dreams 1:54 Golden American Waltzes The 1,000 Strings Do For Love 4:41 2 PAC Changes 4:31 2 PAC How Do You Want It 4:00 2 PAC Still Ballin 2:51 Urban 14 2 Pac California Love (Long Version 6:29 2 Pac California Love 4:03 Pop, Rock & Rap 1 2 Pac & Dr Dre Pac's Life *PO Clean Edit* 3:38 Promo Only Rhythm Radio December 2006 2Pac F. T.I. & Ashanti When I'm Gone 4:20 Away from the Sun 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3:58 Away from the Sun 3 Doors Down Bailen (Reggaeton) 3:41 Tropical Latin September 2002 3-2 Get Funky No More 3:48 Top 40 v. 24 3LW Feelin' You 3:35 Promo Only Rhythm Radio July 2006 3LW f./Jermaine Dupri El Baile Melao (Fast Cumbia) 3:23 Promo Only - Tropical Latin - December … 4 En 1 Until You Loved Me (Valentin Remix) 3:56 Promo Only: Rhythm Radio - 2005/06 4 Strings Until You Love Me 3:08 Rhythm Radio 2005-01 4 Strings Ain't Too Proud to Beg 2:36 M2 4 Tops Disco Inferno (Clean Version) 3:38 Disco Inferno - Single 50 Cent Window Shopper (PO Clean Edit) 3:11 Promo Only Rhythm Radio December 2005 50 Cent Window Shopper -

Michigan's Film Tax Incentive

October 14, 2010 Vol. XXVII No. 3 one copy FREE NORTHWES TERN MICHIGAN COLL EGE WHITE PINEWe hew toP the line; let the chips fall where they may Bioneers Michigan's film tax incentive: Keynote d) Marsha Smith of helping or hurting? Rotary Charities sits down with the White Pine Press to discuss Bioneers, and how can get involved. share the road? NMC Adjunct Faculty member Gary Howe says yes. He founded the pop ular and local online blog mywheelsareturning. com. His goal? Do not be On the set of Rivet Entertainment's production of "Deconstruction" for the Science Channel. Rivet Entertainment, founded by Bill Latka, opened a Traverse City office in large part due to Michigan's film tax incentive. MADDY MESA IPress Staff Writer Ever wanted to go see the set of a movie? local economy, alleged Latka. For instance, every out-of-towner who comes to Michigan Maybe visit the town or city where your if a director wants to shoot a film in a small and spends money which goes back into the favorite movie was filmed? That town may be town downstate: he must find a location and economy. And for people like Latka, having closer then you think. Michigan has become bring his entire cast and crew to town. They production businesses in Michigan has helped the new Hollywood thanks to its film tax the local economy, he has bought a house, incentive. That means any movie production "Since the tax incentive pays taxes and spends money here. Latka Remembering done in the state of Michigan receives a 40 claims that the same pattern will happen percent refundable tax credit causing all kinds started in April 2008, there has when others come back and spend money in Lennon of movie makers to flock to our state.