To Download the PDF File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Asian Heritage Month Report

ASIANASIAN HHERITAGEERITAGE MMONTHONTH REPORTREPORT 20172017 www.asianheritagemanitoba.comwww.asianheritagemanitoba.com TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 ASIAN HERITAGE MONTH OPENING CEREMONY ................................................................................................................................... 5 ASIAN WRITERS’ SHOWCASE ................................................................................................................................................................. 9 ASIAN CANADIAN DIVERSITY FESTIVAL ................................................................................................................................................ 11 ASIAN HERITAGE HIGH SCHOOL SYMPOSIUM ..................................................................................................................................... 13 ASIAN FILM NIGHT REPORT ................................................................................................................................................................. 19 ASIAN CANADIAN FESTIVAL ................................................................................................................................................................. 23 ASIAN HERITAGE MONTH CLOSING CEREMONIES .............................................................................................................................. -

Collection: Green, Max: Files Box: 42

Ronald Reagan Presidential Library Digital Library Collections This is a PDF of a folder from our textual collections. Collection: Green, Max: Files Folder Title: Briefing International Council of the World Conference on Soviet Jewry 05/12/1988 Box: 42 To see more digitized collections visit: https://reaganlibrary.gov/archives/digital-library To see all Ronald Reagan Presidential Library inventories visit: https://reaganlibrary.gov/document-collection Contact a reference archivist at: [email protected] Citation Guidelines: https://reaganlibrary.gov/citing National Archives Catalogue: https://catalog.archives.gov/ WITHDRAWAL SHEET Ronald Reagan Library Collection Name GREEN, MAX: FILES Withdrawer MID 11/23/2001 File Folder BRIEFING INTERNATIONAL COUNCIL & THE WORLD FOIA CONFERENCE ON SOVIET JEWRY 5/12/88 F03-0020/06 Box Number THOMAS 127 DOC Doc Type Document Description No of Doc Date Restrictions NO Pages 1 NOTES RE PARTICIPANTS 1 ND B6 2 FORM REQUEST FOR APPOINTMENTS 1 5/11/1988 B6 Freedom of Information Act - [5 U.S.C. 552(b)] B-1 National security classified Information [(b)(1) of the FOIA) B-2 Release would disclose Internal personnel rules and practices of an agency [(b)(2) of the FOIA) B-3 Release would violate a Federal statute [(b)(3) of the FOIA) B-4 Release would disclose trade secrets or confidential or financial Information [(b)(4) of the FOIA) B-8 Release would constitute a clearly unwarranted Invasion of personal privacy [(b)(6) of the FOIA) B-7 Release would disclose Information compiled for law enforcement purposes [(b)(7) of the FOIA) B-8 Release would disclose Information concerning the regulation of financial Institutions [(b)(B) of the FOIA) B-9 Release would disclose geological or geophysical Information concerning wells [(b)(9) of the FOIA) C. -

“A Matter of Deep Personal Conscience”: the Canadian Death-Penalty Debate, 1957-1976

“A Matter of Deep Personal Conscience”: The Canadian Death-Penalty Debate, 1957-1976 by Joel Kropf, B.A. (Hons.) A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario July 31,2007 © 2007 Joel Kropf Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Library and Bibliotheque et Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-33745-5 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-33745-5 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce,Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve,sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet,distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform,et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

The Canadian Japanese, Redress, and the Power of Archives R.L

The Canadian Japanese, Redress, and the Power of Archives R.L. Gabrielle Nishiguchi (Library and Archives Canada) [Originally entitled: From the Shadows of the Second World War: Archives, Records and Cana- dian Japanese]1 I am a government records archivist at Library and Archives Canada2 who practises macro- appraisal. It should be noted that the ideas of former President of the Bundesarchiv, Hans Booms3, inspired Canadian Terry Cook, the father of macro-appraisal -which has been the appraisal approach of my institution since 1991. “If there is indeed anything or anyone qualified to lend legitimacy to archival appraisal,” Hans Booms wrote in 1972, ‘it is society itself….”4 As Cook asserts, Booms was “perhaps the first 1 This Paper was delivered on 15 October 2019 at the Conference: “Kriegsfolgenarchivgut: Entschädigung, Lasten- ausgleich und Wiedergutmachung in Archivierung und Forschung” hosted by the Bundesarchiv, at the Bundesar- chiv-Lastenausgleichsarchiv, Bayreuth, Germany. The views, thoughts and opinions expressed in this paper belong solely to the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Library and Archives Canada. 2 Library and Archives Canada had its beginnings in 1872 as the Archives Branch of the Department of Agriculture. In 1903, the Archives absorbed the Records Branch of the Department of the Secretary of State. It was recognized by statute as the Public Archives of Canada in 1912 and continued under this name until 1987 when it became the National Archives of Canada as per the National Archives of Canada Act, R.S.C. , 1985, c. 1 (3rd Supp.), accessed 10 January 2020. In 2004, the National Archives of Canada and the National Library of Canada. -

Source 4.12 a Post-War History of Japanese Canadians

LESSON 4 SOURCE 4.12 A POST-WAR HISTORY OF JAPANESE CANADIANS With World War II winding down, the Canadian government started In 1947, the government agreed to an investigation into Japanese planning for the future of Japanese Canadians. In the United States of Canadian property loss when it could be demonstrated that properties America, incarcerated Japanese Americans won a December 1944 were not sold at “fair market value” (Politics of Racism, p. 147). Supreme Court decision which ruled that though the wartime internment Cabinet wanted to keep the investigation limited in scope and cost, of Japanese Americans was constitutional, it ruled in a separate decision and managed to have it limited to cases where the Custodian had not that loyal citizens must be released. Japanese Americans started disposed of the property near market value. Justice Henry Bird was returning to their homes on the coast in January 1945. appointed to represent the government in the Royal Commission of In January 1945, Japanese Canadians were forced by the Canadian Japanese Canadian Losses. He tried to dispense with hearings in government to choose between “repatriation” (exile) to Japan or order to streamline claims. Justice Bird concluded his investigation in “dispersal” east of the Rocky Mountains. 10,632 people signed up for April 1950. He announced that the Custodian performed his job deportation to Japan, however, more than half later rescinded their competently. He also reported that sometimes properties were not sold signatures. In the end almost 4,000 were deported to Japan. Japanese at a fair market value. Canadians who wished to remain in Canada could not return to B.C. -

LEGI SLATIVE ASSEMBLY of MANITOBA Thursday, 2 May, 1985

LEGI SLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF MANITOBA Thursday, 2 May, 1985. Time - 2:00 p.m. in this House, and by the Minister of Industry, Tr ade and Te chnology. OPENING PRAYER by Mr. Speaker. My colleagues and I believe that, on the whole, the meeting was productive, and I think the federal MR. SPEAKER, Hon. J. Walding: Presenting Petitions representatives would agree. Reading and Receiving Petitions . Presenting Although the precise details remain to be worked Reports by Standing and Special Committees . out, we were able to secure federal agreement to move ahead as soon as possible with $6 million in boxcar MINISTERIAL STATEMENTS rehabilitation work for the Churchill line. Mr. Speaker, the costs are to be split 50-50 between Canada and AND TABLING OF REPORTS Manitoba as specified in the sub-agreement. When Manitoba undertook to share in rolling stock MR. SPEAKER: The Honourable Minister of Northern costs it was with three main understandings in mind: Affairs. that the cars would be required by C.N. to service the Port of Churchill; I HON. H. HARAPIAK: Mr. Speaker, would like to table that the rehabilitation work would be done in the Annual Reports for Moose Lake Loggers Ltd., the Manitoba at the C.N. Shops in Transcona; and Communities Economic Development Fund, and the finally, Channel Area Loggers Ltd. that work would also proceed simultaneously here in Manitoba on development of a new light MR. SPEAKER: The Honourable Minister of Education. hopper car. We are satisfied, after last night's meeting, that HON. M. HEMPHILL: Mr. Speaker, I would like to table provincial investment in improved rolling stock remains the Annual Financial Report for the year ended March justified. -

Japanese Canadians Japanese Canadians Have Lived in Canada Since the 1870S, Mostly in British Columbia

Context card EC 99671- JC (03/2020) Case study: Japanese Canadians Japanese Canadians have lived in Canada since the 1870s, mostly in British Columbia. In this province, they worked as fishers, farmers and business owners. Due to racism, the British Columbia government banned Japanese Canadians who lived there from voting in provincial elections. This ban also affected their right to vote in federal elections. Canada fought with Japan in the Second World War (1939–1945). During this time, Japanese Canadians lost even more democratic rights. The government thought that Japanese Canadians threatened Canada’s security and forced them to move away from the Pacific Coast. They could not vote in federal elections, no matter which province they lived in. Japanese Canadians were finally allowed to vote in all federal and provincial elections in 1948. In the years that followed, Japanese Canadians asked for an apology. They finally got one in 1988, when the federal government formally Source: CWM 20150279-001_p21, George Metcalf Archival apologized for past wrongs. Collection, Canadian War Museum Context Cards_Language Learner_EN.indd 1 2020-03-05 12:58 PM Japanese Japanese 1871 Canadians 1895 Canadians Source: Image C-07918 courtesy of the Royal BC Museum and Archives British Columbia joins Confederation – it becomes part of Canada. Canada now includes a small population of Japanese Canadians. They have Source: JCCC Original Photographic Collection, Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre, 2001.4.119 the right to vote in provincial and federal elections if they: The British Columbia government passes a law • are male, that bans Japanese Canadians from voting in • are age 21 or older, and provincial elections. -

Legislating Multiculturalism and Nationhood: the 1988 Canadian Multiculturalism Act

Legislating Multiculturalism and Nationhood: The 1988 Canadian Multiculturalism Act VARUN UBEROI Brunel University Prominent scholars discuss the Canadian policy of multiculturalism (Kymlicka, 2012: 10; Modood, 2013: 163; Taylor, 2015: 336). But we have little historical knowledge about this policy beyond why it was intro- duced in 1971 (Joshee, 1995; Temlini, 2007) and later bolstered by a clause in the 1982 Charter of Rights and Freedoms (Uberoi, 2009). Hence, we know little, for example, about the reasons, calculations and strategies that were used in the 1980s to increase funding for this policy and to give this policy its own federal department (Abu-Laban, 1999: 471; Karim, 2002: 453). In this article I will try to increase our historical know- ledge of this policy. I use new archival and elite interview data to show how the legislation that enshrined this policy of multiculturalism in law in 1988, the Canadian Multiculturalism Act, came into existence. In addition to enshrining this policy in law, the act is significant in at least three ways. First, the act altered the policy of multiculturalism by empowering it to encourage all federal departments to reflect Canada’s ethnic diversity among its staff and to promote respect for this diversity too. Second, the act increased oversight of the policy as it compels the Acknowledgments: I am grateful to Desmond King and Will Kymlicka for their comments on a very early draft of this piece and to Alexandra Dobrowolsky, Matthew James, Tariq Modood, Nasar Meer, Bhikhu Parekh and Elise Uberoi for their comments on later drafts. I am grateful to Solange Lefebvre for her help with the French abstract. -

Blanshay, Linda Sema (2001) the Nationalisation of Ethnicity: a Study of the Proliferation of National Mono-Ethnocultural Umbrella Organisations in Canada

Blanshay, Linda Sema (2001) The nationalisation of ethnicity: a study of the proliferation of national mono-ethnocultural umbrella organisations in Canada. PhD thesis http://theses.gla.ac.uk/3529/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] THE NATIONALISATION OF ETHNICITY: A STUDY OF THE PROLIFERATION OF NATIONAL MONO ETHNOCULTURAL UMBRELLA ORGANISATIONS IN CANADA Linda Serna Blanshay Ph.D. University of Glasgow Department of Sociology and Anthropology January, 2001. © Linda SemaBlanshay, 2001 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS lowe heartfelt thanks to many people. My Ph.D experience was made profoundly rewarding because of the support offered by participants in the study, my colleagues, and my family and friends. At the end of the day, it is their generosity of spirit that remains with me and has enriched this fascinating academic journey. There are some specific mentions of gratitude that I must make. Thanks to the Rotary Foundation, for first shipping me out to Glasgow as I requested on my application. The Rotary program emphasized 'service above self which is an important and appropriate theme in which to depart on sociological work ofthis kind. -

19-24 ANNUAIRE DU CANADA 19.4 Circonscriptions Électorales, Votes

19-24 ANNUAIRE DU CANADA 19.4 Circonscriptions électorales, votes recueillis et noms des députés élus à la Chambre des communes aux trente-troisièmes élections générales du 4 septembre 1984 (suite) Population, Total, Tolal Nom du député Affili circonscription recen voies obtenu ation électorale sement recueillis par le politique1 de 1981 (votes député rejetés compris) l.ondon-Est 79,890 .18,655 18,154 Jim Jepson P.C. London-Middlesex 84,225 39,710 18,586 Terry Clifford P.C. I.ondon-Ouesl 115,921 67,375 34,517 Tom Hockin P.C. Mississauga-Nord 192,795 95,618 47,124 Robert Horner P.C. Mississauga-Sud 122,262 58,614 32,946 Don Blenkarn P.C. Ncpean-Carlcton 121,937 74,737 41,663 Bill Tupper P.C. Niagara Falls 83,146 41,879 22,852 Rob Nicholson P.C. Nickel Bell 87,957 44,660 17,141 John R. Rodriguez N.P.D. Nipissing 68,738 36,700 17,247 Moe Mantha P.C. Northumberland 76,775 38,785 24,060 George Hees P.C. Ontario 111,134 62,884 35,163 Scott Fennell P.C. Oshawa 117,519 59,620 25,092 Ed Broadbent- N.P.D. Oltawa-Carleton 132,508 77,922 34,693 Barry Turner P.C. Ottawa-Centre 87,502 52,271 17,844 Michael Cassidy N.P.D. Ottawa-Vanier 79,102 43,934 21,401 Jean-Robert Gauthier Lib. Ottawa-Ouest 89,596 54,739 26,591 David Daubncy P.C. Oxford 85,920 45.137 25,642 Bruce Halliday P.C. -

Rt. Hon. John Turner Mg 26 Q 1 Northern Affairs Series 3

Canadian Archives Direction des archives Branch canadiennes RT. HON. JOHN TURNER MG 26 Q Finding Aid No. 2018 / Instrument de recherche no 2018 Prepared in 2001 by the staff of the Préparé en 2001 par le personnel de la Political Archives Section Section des archives politique. -ii- TABLE OF CONTENT NORTHERN AFFAIRS SERIES ( MG 26 Q 1)......................................1 TRANSPORT SERIES ( MG 26 Q 2) .............................................7 CONSUMER AND CORPORATE AFFAIRS SERIES (MG 26 Q 3) ....................8 Registrar General.....................................................8 Consumer and Corporate Affairs.........................................8 JUSTICE SERIES (MG 26 Q 4)................................................12 FINANCE SERIES (MG 26 Q 5) ...............................................21 PMO SERIES ( MG 26 Q 6)....................................................34 PMO Correspondence - Sub-Series (Q 6-1) ...............................34 Computer Indexes (Q 6-1).............................................36 PMO Subject Files Sub-Series (Q 6-2) ...................................39 Briefing Books - Sub-Series (Q 6-3) .....................................41 LEADER OF THE OPPOSITION SERIES (MG 26 Q 7)..............................42 Correspondence Sub-Series (Q 7-1) .....................................42 1985-1986 (Q 7-1) ...................................................44 1986-1987 (Q 7-1) ...................................................48 Subject Files Sub-Series (Q 7-2)........................................73 -

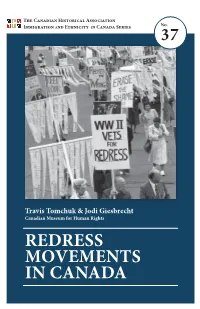

REDRESS MOVEMENTS in CANADA Editor: Marlene Epp, Conrad Grebel University College University of Waterloo

The Canadian Historical Association No. Immigration And Ethnicity In Canada Series 37 Travis Tomchuk & Jodi Giesbrecht Canadian Museum for Human Rights REDRESS MOVEMENTS IN CANADA Editor: Marlene Epp, Conrad Grebel University College University of Waterloo Series Advisory Committee: Laura Madokoro, McGill University Jordan Stanger-Ross, University of Victoria Sylvie Taschereau, Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières Copyright © the Canadian Historical Association Ottawa, 2018 Published by the Canadian Historical Association with the support of the Department of Canadian Heritage, Government of Canada ISSN: 2292-7441 (print) ISSN: 2292-745X (online) ISBN: 978-0-88798-296-5 Travis Tomchuk is the Curator of Canadian Human Rights History at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights, and holds a PhD from Queen’s University. Jodi Giesbrecht is the Manager of Research & Curation at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights, and holds a PhD from the University of Toronto. Cover image: Japanese Canadian redress rally at Parliament Hill, 1988. Photographer: Gordon King. Credit: Nikkei National Museum 2010.32.124. REDRESS MOVEMENTS IN CANADA Travis Tomchuk & Jodi Giesbrecht Canadian Museum for Human Rights All rights reserved. No part of this publication maybe reproduced, in any form or by any electronic ormechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the Canadian Historical Association. Ottawa, 2018 The Canadian Historical Association Immigration And Ethnicity In Canada Series Booklet No. 37 Introduction he past few decades have witnessed a substantial outpouring of Tapologies, statements of regret and recognition, commemorative gestures, compensation, and related measures on behalf of all levels of government in Canada in order to acknowledge the historic wrongs suffered by diverse ethnic and immigrant groups.