Tom Marioni Know Where You Are and What Is Going on an Excerpt from a Memoir in Progress by Kathan Brown

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Editions 2013: Reviews and Listings of Recent Prints And

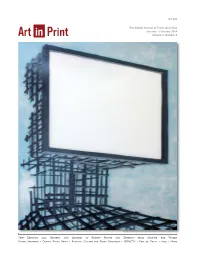

US $25 The Global Journal of Prints and Ideas January – February 2014 Volume 3, Number 5 New Editions 2013: Reviews and Listings of Recent Prints and Editions from Around the World Dasha Shishkin • Crown Point Press • Fanoon: Center for Print Research • IMPACT8 • Prix de Print • ≤100 • News international fi ne ifpda print dealers association 2014 Calendar Los Angeles IFPDA Fine Print Fair January 15–19 laartshow.com/fi ne-print-fair San Francisco Fine Print Fair January 24–26 Details at sanfrancisco-fi neprintfair.com IFPDA Foundation Deadline for Grant Applications April 30 Guidelines at ifpda.org IFPDA Book Award Submissions due June 30 Guidelines at ifpda.org IFPDA Print Fair November 5– 9 Park Avenue Armory, New York City More at PrintFair.com Ink Miami Art Fair December 3–7 inkartfair.com For IFPDA News & Events Visit What’s On at ifpda.org or Subscribe to our monthly events e-blast Both at ifpda.org You can also follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram! The World’s Leading Experts www.ifpda.org 250 W. 26th St., Suite 405, New York, NY 10001-6737 | Tel: 212.674.6095 | [email protected] Art in Print 2014.indd 1 12/6/13 4:22 PM January – February 2014 In This Issue Volume 3, Number 5 Editor-in-Chief Susan Tallman 2 Susan Tallman On Being There Associate Publisher Kate McCrickard 4 Julie Bernatz Welcome to the Jungle: Violence Behind the Lines in Three Suites of Prints by Managing Editor Dasha Shishkin Dana Johnson New Editions 2013 Reviews A–Z 10 News Editor Isabella Kendrick Prix de Print, No. -

WINTER 2014.Indd

The Print Club of New York Inc Winter 2014 President’s Greeting Mona Rubin t’s hard to believe that I am entering my fourth year as President. The beginning of a new year is a good I time to reflect on highlights from the past twelve months and to focus on how to make this new season a meaningful one for our members. One development that stands out for me is how nation- ally connected the Print Club has become. I receive mail- ings from printers and publishers all over the country, as far away as Seattle. We are pleased to welcome an impor- tant new member this year, Sue Oehme, who has pub- lished prints by several of our Presentation Print artists out of her studio in Colorado – Oehme Graphics. Although she is a distance away, I am certain she will make important contributions to the club with her wealth Our Prints Ready to Ship. PHOTO COURTESY OF ROBERT of knowledge and interesting group of artists. BLACKBURN PRINTMAKING WORKSHOP Kay Deaux has continued to provide us with extraordi- nary events, which cover a broad range of styles and inter- this in mind if any of you see an interesting print show or ests. It saddens me that more members do not take have an idea you would like to share. Gillian is always advantage of these opportunities, especially since they are available to discuss writing an article. (Contact her at an integral benefit of membership. Kay is planning to send [email protected].) a survey in the next few months to try to understand what Our two newest Board Members, Kimberly Henrikson modifications may increase attendance. -

Art Prints and the Uniform Commercial Code

Indiana Law Journal Volume 72 Issue 2 Article 15 Spring 1997 Unique or Ubiquitous: Art Prints and the Uniform Commercial Code Wendy C. Lowengrub Indiana University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj Part of the Commercial Law Commons, and the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons Recommended Citation Lowengrub, Wendy C. (1997) "Unique or Ubiquitous: Art Prints and the Uniform Commercial Code," Indiana Law Journal: Vol. 72 : Iss. 2 , Article 15. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj/vol72/iss2/15 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Unique or Ubiquitous: Art Prints and the Uniform Commercial Code WENDY C. LOWENGRUB* Law, in its search for truth and justice through precedence and tradition, often ignores the fundamental meaning of an act or an object. The fine art print is one such example. A recent case in the Southern District of New York held that art prints are unique: "two prints by the same artist and from the same plate are not interchangeable."' The court refused to allow the seller of a Picasso print to cure under the Uniform Commercial Code ("U.C.C.") section 2-5082 by offering a substitute print from the same plate, printed at the same time, and signed by Picasso to the buyer who claimed breach of contract because of a forged signature on the initial print.' Presumably, the New York court was dazzled by the cost of the print ($1.68 million) and by the argument that printing plates wear significantly during printing. -

Fall 2019 Rizzoli Fall 2019

I SBN 978-0-8478-6740-0 9 780847 867400 FALL 2019 RIZZOLI FALL 2019 Smith Street Books FA19 cover INSIDE LEFT_FULL SIZE_REV Yeezy.qxp_Layout 1 2/27/19 3:25 PM Page 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS RIZZOLI Marie-Hélène de Taillac . .48 5D . .65 100 Dream Cars . .31 Minä Perhonen . .61 Achille Salvagni . .55 Missoni . .49 Adrian: Hollywood Designer . .37 Morphosis . .52 Aēsop . .39 Musings on Fashion & Style . .35 Alexander Ponomarev . .68 The New Elegance . .47 America’s Great Mountain Trails . .24 No Place Like Home . .21 Arakawa: Diagrams for the Imagination . .58 Nyoman Masriadi . .69 The Art of the Host . .17 On Style . .7 Ashley Longshore . .43 Parfums Schiaparelli . .36 Asian Bohemian Chic . .66 Pecans . .40 Bejeweled . .50 Persona . .22 The Bisazza Foundation . .64 Phoenix . .42 A Book Lover’s Guide to New York . .101 Pierre Yovanovitch . .53 Bricks and Brownstone . .20 Portraits of a Master’s Heart For a Silent Dreamland . .69 Broken Nature . .88 Renewing Tradition . .46 Bvlgari . .70 Richard Diebenkorn . .14 California Romantica . .20 Rick Owens Fashion . .8 Climbing Rock . .30 Rooms with a History . .16 Craig McDean: Manual . .18 Sailing America . .25 David Yarrow Photography . .5 Shio Kusaka . .59 Def Jam . .101 Skrebneski Documented . .36 The Dior Sessions . .50 Southern Hospitality at Home . .28 DJ Khaled . .9 The Style of Movement . .23 Eataly: All About Dolci . .40 Team Penske . .60 Eden Revisited . .56 Together Forever . .32 Elemental: The Interior Designs of Fiona Barratt Campbell .26 Travel with Me Forever . .38 English Gardens . .13 Ultimate Cars . .71 English House Style from the Archives of Country Life . -

The Museum Off Modern Art

The Museum off Modern Art For Immediate Release November 1987 FOR 25 YEARS: CROWN POINT PRESS November 20, 1987 - February 9, 1988 The twenty-fifth anniversary of Crown Point Press, the distinguished California print workshop and publisher, is celebrated in an exhibition at The Museum of Modern Art from November 20, 1987, to February 9, 1988. Organized by Riva Castleman, director of the Department of Prints and Illustrated Books, FOR 25 YEARS: CROWN POINT PRESS includes approximately forty works published by Crown Point Press, most of which are from a large donation commemorating its quarter century. Artists represented in the exhibition include John Cage, Francesco Clemente, Joan Jonas, Elaine de Kooning, Robert Mangold, Tom Marioni, Judy Pfaff, Steve Reich, Ed Ruscha, David True, and William Wiley (complete list attached). Founded in 1962 in the basement of director Kathan Brown's Berkeley home, Crown Point Press was a print workshop organized to produce bound books of prints. The complete production process of the early books, which included editions by Wayne Thiebaud and Richard Diebenkorn, was considered part of the art work. In 1970 Crown Point printed its first non-book work, color aquatints by Thiebaud, published by the newly-formed Parasol Press in New York. Two years later Brown moved her etching presses to a studio in Oakland, where she remained until 1986. During the years 1971-76 Crown Point continued to print for other publishers, working with such New York artists as Sol LeWitt, Brice - more - 11 West 53 Street New York, NY 10019-5486 Tel: 212-708-9400 Coble; MPDERNART Telex: 62370 MODART - 2 - Marden, Chuck Close, Dorothea Rockburne, Robert Mangold, Dan Flavin, and Helen Frankenthaler. -

Artists Working at Crown Point Press September 1, 2013 - January 5, 2014

Updated Tuesday, September 17, 2013 | 4:44:53 PM Last updated Tuesday, September 17, 2013 Updated Tuesday, September 17, 2013 | 4:44:53 PM National Gallery of Art, Press Office 202.842.6353 fax: 202.789.3044 National Gallery of Art, Press Office 202.842.6353 fax: 202.789.3044 Yes, No, Maybe: Artists Working at Crown Point Press September 1, 2013 - January 5, 2014 To order publicity images: Publicity images are available only for those objects accompanied by a thumbnail image below. Please email [email protected] or fax (202) 789-3044 and designate your desired images, using the “File Name” on this list. Please include your name and contact information, press affiliation, deadline for receiving images, the date of publication, and a brief description of the kind of press coverage planned. Links to download the digital image files will be sent via e-mail. Usage: Images are provided exclusively to the press, and only for purposes of publicity for the duration of the exhibition at the National Gallery of Art. All published images must be accompanied by the credit line provided and with copyright information, as noted. Important: The images displayed on this page are for reference only and are not to be reproduced in any media. File Name: 3631-020.jpg Richard Diebenkorn Touched Red (working proof 8), 1991 color aquatint, spitbite aquatint, softground etching, and drypoint with pasted-down elements plate: 24 x 16 (61 x 40.6) sheet: 36 x 26 1/2 (91.4 x 67.3) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Crown Point Press, 1996 © The Richard Diebenkorn Foundation Chuck Close John (working proof for unpublished print), 1972 photo-etching in black sheet: 23 3/4 × 14 3/4 in. -

WAYNE THIEBAUD Born 1920, Mesa, AZ

WAYNE THIEBAUD born 1920, Mesa, AZ BIOGRAPHY 1936 Works briefly in Animation Department of Walt Disney Studios, Los Angeles, CA. 1937 Attends Frank Wiggins Trade School to study commercial art, Los Angeles, CA. 1940-41 Attends Long Beach Junior College (now Long Beach City College), Long Beach, CA. 1942-45 Serves in United States Army Air Force. In the last months of service is transferred to First Air Force Motion Picture Unit, Culver City, CA. 1946–49 Works as Layout Designer and Cartoonist in Advertising Department for Rexall Drug Company, Los Angeles, CA. Meets Sculptor Robert Mallary, a co-worker at Rexall. 1948 Participates in first major museum exhibition, Artists of Los Angeles and Vicinity, Los Angeles County Museum (now Los Angeles County Museum of Art). 1949–50 Attends San Jose State College (now San Jose State University), San Jose, CA. 1950–53 Transfers to California State College (now California State University), Sacramento, CA. Receives BA in 1951; receives MA in 1953 (art major focused on art history, theory, and education). 1951 First solo show, Influences on a Young Painter, E.B. Crocker Art Gallery, Sacramento, CA. 1950–59 Serves as Exhibit Designer for annual art exhibition of the California State Fair and Exposition, Sacramento, CA. 1951–60 Receives appointment as Instructor of Art, Sacramento Junior College (now Sacramento City College). Chairman of Art Department (1954–56, 1958–60). 1954 Establishes Patrician Films; produces educational art films, including Color on a Stone and Modern Art Series, at Bailey Films, Hollywood, CA. 1956–57 Takes leave of absence from teaching to live in New York, NY. -

Kathan Brown Oral History Transcript

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art Regional Oral History Office 75th Anniversary The Bancroft Library Oral History Project University of California, Berkeley SFMOMA 75th Anniversary KATHAN BROWN Founder, Crown Point Press Interviews conducted by Jess Rigelhaupt in 2007 Copyright © 2008 by San Francisco Museum of Modern Art Funding for the Oral History Project provided in part by Koret Foundation. Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the nation. Oral History is a method of collecting historical information through tape-recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well-informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. The tape recording is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The corrected manuscript is bound with photographs and illustrative materials and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and in other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ********************************* All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Kathan Brown, dated March 29, 2007. This manuscript is made available for research purposes. All copyrights and other intellectual property rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. -

2019 Annual Report

2019 Annual Report Fiscal Year 2019 Washington, DC TABLE OF CONTENTS President’s Foreword ...........................................................5 Director’s Statement ............................................................9 Board of Trustees and Committees................................. 11 Year in Review ......................................................................13 Treasurer’s Report and Financial Statements ...............35 Acquisitions .......................................................................... 41 Changes of Attribution ..................................................... 85 Exhibitions and Loans ........................................................89 Gifts and Donors ............................................................. 109 Staff List ...............................................................................121 PRESIDENT’S FOREWORD At the dedication of the National Gallery of Art in 1941, Paul Mellon spoke of his father’s hope that the museum he had founded “would become not a static but a living institution, growing in usefulness and importance to artists, scholars, and the general public.” Founder Andrew W. Mellon envisioned “a joint enterprise on the part of the Government, on the one hand, and of magnanimous citizens, on the other.” This public- private partnership, now nearly eight decades later, makes it possible for the Gallery to serve millions of visitors each year. I am deeply grateful for the steadfast support of the president and the Congress of the United States. Carrying -

Journal 1999:Journal 1999/10

THE CALIFORNIA PRINTMAKER THE JOURNAL OF THE CALIFORNIA SOCIETY OF PRINTMAKERS ISSUE NO. 1, OCTOBER 1999 “I am certain that many printers have felt this extreme fire of collaboration… The wizardry and alchemy that is wielded by the creative technician enriches the experience of the final image, but it must never dominate or dictate the creative thrust. If highly technical skills override the concept of the artist, the works become hollow. To become a breathing life force, the artistic ingredient must be felt rather than just used as a display of surfaces, textures, and colors—beautiful but lacking in substance. The work must dance on the edge of the abyss.” —Bob Blackburn Bob Blackburn was named an honorary member of the CSP in 1999. A major force in contemporary printmaking, he founded and continues to direct the Printmaking Workshop in Manhattan and has collaborated with many of the most important artists of our time. Editor’s Note In recent years and for the foreseeable fell away as each interview lead me to resented here so that they can be appreci- future, the editorship of the CSP journal is another with its own logic, thanks in part ated in their own terms and humanity. I an unpaid and once-only job taken on by to the generosity of each person with hope the opinions and representations a willing member of the Society. I had no whom I spoke. Doris recommended that I here will stimulate thought, discussion, idea when I began this year that it would speak with Ruth Fine and Ruth recom- and even controversy, and that all of be such an interesting adventure. -

A Quest for the Golden Fleece

A Quest for the Golden Fleece Donald Farnsworth A Quest for the Golden Fleece Rarely have I encountered an entangled mat of cellulose fibers I didn’t appreciate in one way or another. Whether textured or smooth, pre- cious or disposable, these hardy amalgams of hydrogen-bonded fibers have changed the world many times over. For centuries, human history has been both literally written on the surface of paper and embedded deep within its structure. In folded and bound form, mats of cellulose fibers ushered in the Enlightenment; by enabling multiple iterations and revisions of an idea to span generations, they have facilitated the design of airships and skyscrapers, or the blueprints and calculations that made possible the first human footsteps on the moon. Generally speaking, we continue to recognize paper by a few basic characteristics: it is most often thin, portable, flexible, and readily ac- cepting of ink or inscription. There is, however, a particular sheet that is superlatively impressive, exhibiting an unintentional and unpreten- tious type of beauty. At first glance and in direct light, it may trick you into thinking it is merely ordinary paper; when backlit, the care- ful viewer may detect subtle hints of its historical pedigree via telltale watermarks or chain and laid lines. Only when viewed under a raking light does its extraordinary surface emerge with clarity, containing endlessly variegated impressions of the fibrous felts between which it was made: a galaxy of fibers, ready and waiting for a collaboration with an opportune stroke of chalk or splash of paint. What follows is the story of a quest to make this specific incarnation of paper: a sheet Albrecht Durer - Construction of a Spiral Line, 1525 Copyright © 2017 Donald Farnsworth, all rights reserved. -

Graphic Impressions the Newsletter of SGC International Summer 2014

Graphic Impressions The Newsletter of SGC International Summer 2014 In this issue: Letter from the President David Jones / Letter from Editor Liz Klimek / Segura Reborn at University of Notre Dame by Sarah Kirk Hanley / 2015 Conference Call for Participation / Confer- ence Wrap -up: Bridges San Francisco by Susan Belau / Digital Culture by Eli McGlothern / Interview: Sarah McEneaney at Dolphin Press & Print by Eva Wylie / THE ISCA & the Future of Copier Art? by Julia Arredondo / International Focus: Global research in Printmaking by Alberto Meza / Letter from student representative Cindy Tidler / Announcements BOARD OF DIRECTORS President David Jones Columbia College [email protected] Vice President of Internal Affairs Kevin Haas Washington State University [email protected] Vice President of External Affairs Nichole Pietrantoni Whitman College [email protected] Treasurer Michelle Martin University of Tulsa Letter from the Editor [email protected] Elizabeth Klimek Secretary Jessica Meuninick-Granger Dear SGCI members, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee [email protected] Change. Sometimes we fear it, other times it is wel- come, and always inevitable. Change is relevant to this Member at Large Charles Beneke issue of GI. We start off with a letter from our new presi- [email protected] dent, David Jones. New information for the upcoming The University of Akron Myers School of Art SGCI conference in Knoxville is in this issue as well. We read about digital culture, the relocation of a Segura International Member at Large Michael Kempson printmaking studio, and pose the question, “What is the University of New South Wales, Australia future of copier art?” [email protected] International Member at Large I hope everyone has a great summer, whether you are off to residencies, starting a Anna Nicholson new body of work, or just relaxing and sunning by the pool, have a great one.