Kathan Brown Oral History Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Editions 2013: Reviews and Listings of Recent Prints And

US $25 The Global Journal of Prints and Ideas January – February 2014 Volume 3, Number 5 New Editions 2013: Reviews and Listings of Recent Prints and Editions from Around the World Dasha Shishkin • Crown Point Press • Fanoon: Center for Print Research • IMPACT8 • Prix de Print • ≤100 • News international fi ne ifpda print dealers association 2014 Calendar Los Angeles IFPDA Fine Print Fair January 15–19 laartshow.com/fi ne-print-fair San Francisco Fine Print Fair January 24–26 Details at sanfrancisco-fi neprintfair.com IFPDA Foundation Deadline for Grant Applications April 30 Guidelines at ifpda.org IFPDA Book Award Submissions due June 30 Guidelines at ifpda.org IFPDA Print Fair November 5– 9 Park Avenue Armory, New York City More at PrintFair.com Ink Miami Art Fair December 3–7 inkartfair.com For IFPDA News & Events Visit What’s On at ifpda.org or Subscribe to our monthly events e-blast Both at ifpda.org You can also follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram! The World’s Leading Experts www.ifpda.org 250 W. 26th St., Suite 405, New York, NY 10001-6737 | Tel: 212.674.6095 | [email protected] Art in Print 2014.indd 1 12/6/13 4:22 PM January – February 2014 In This Issue Volume 3, Number 5 Editor-in-Chief Susan Tallman 2 Susan Tallman On Being There Associate Publisher Kate McCrickard 4 Julie Bernatz Welcome to the Jungle: Violence Behind the Lines in Three Suites of Prints by Managing Editor Dasha Shishkin Dana Johnson New Editions 2013 Reviews A–Z 10 News Editor Isabella Kendrick Prix de Print, No. -

Explorations of the Painted Real

EXPLORATIONS OF THE PAINTED REAL: TECHNOLOGICAL MEDIATION IN THE WORK OF FOUR ARTISTS. By Gina Margareta Heyer Thesis presented inpartial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in Visual Arts at the University of Stellenbosch Supervisor: Dr. Stella Viljoen (thesis) Co-supervisor: Mr. Vivian H. van der Merwe (practical) March 2011 Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. 2 March 2011 Copyright © 2011 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved i Abstract This thesis is an investigation into the relationship between photorealistic painting and specific devices used to aid the artist in mediating the real. The term 'reality' is negotiated and a hybrid theoretical approach to photorealism, including mimesis and semiotics, is suggested. Through careful analysis of Vermeer's suspected use of the camera obscura, I argue that camera vision already started in the 17th century, thus signalling the dramatic shift from the classical Cartesian perspective scopic regime to the model of vision offered by the camera long before the advent of photography. I suggest that contemporary photorealist painters do not just merely and objectively copy, but use photographic source material with a sophisticated awareness in response to a rapidly changing world. Through an examination of the way in which the camera obscura and photographic camera are used in the works of four artists, I suggest that a symbiotic relationship of subtle tensions between painting and photographic technology emerges. -

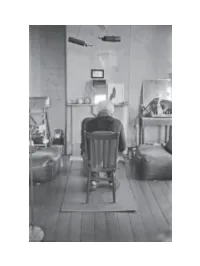

Robert Bechtle Oral History Transcript

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art Regional Oral History Office 75th Anniversary The Bancroft Library Oral History Project University of California, Berkeley SFMOMA 75th Anniversary ROBERT BECHTLE Painter Professor of Art, San Francisco State University, 1978-1999 SFMOMA Board of Trustees, 2006-2009 Interview conducted by Jess Rigelhaupt in 2007 Copyright © 2008 by San Francisco Museum of Modern Art Funding for the Oral History Project provided in part by Koret Foundation. ii Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the nation. Oral History is a method of collecting historical information through tape-recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well-informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. The tape recording is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The corrected manuscript is bound with photographs and illustrative materials and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and in other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ********************************* All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Robert Bechtle, dated October 22, 2007. This manuscript is made available for research purposes. -

Robert Bechtle: New Work

NEW WORK SAN FRANCISCO MUSEUM OF MODERN ART ROBERT BECHTLE : NEW WORK SEPTEMBER 10 - DECEMBER 1, 1991 Born in San Francisco in 1932, Robert Bechtle studied at the California College of Arts and Crafts in Oakland, and since 1968 has taught painting at San Francisco State University. In the late sixties and early seventies, when Bechtle became well-known nationally, his work was usually seen together with that of Richard Estes, Chuck Close, and Malcolm Morley, among others, as representing a new style called Photo Realism or New Realism. Although the relationship of Bechtle's work to photography was evident and much remarked upon, critical discussion generally centered on its subject matter-ordinary views of suburban streets and houses, occasionally with their inhabitants-and the artist's resolute avoidance of the heroic stance associated with Abstract Expressionism.1 Yet Bechtle, more than the other Photo Realim, chose to paint a particular kind of photograph, the ordinarysnapshot of his family, for example, posed in front of a station wagon. His choice was no accident, as he explained at the time: "When I'm photographing a car in front of a house I try to keep in mind what a real estate photographer would do if he were taking a picture of the house and try for that quality." 2 Other Photo Realists. to be sure, made paintings from photographs that could have been snapshots. But in the paintings themselves, only Bechtle's had the atmosphere of ordinary, family photographs because he purposely avoided the virtuoso effects that for the most part characterized the work of his colleagues. -

La Mamelle and the Pic

1 Give Them the Picture: An Anthology 2 Give Them The PicTure An Anthology of La Mamelle and ART COM, 1975–1984 Liz Glass, Susannah Magers & Julian Myers, eds. Dedicated to Steven Leiber for instilling in us a passion for the archive. Contents 8 Give Them the Picture: 78 The Avant-Garde and the Open Work Images An Introduction of Art: Traditionalism and Performance Mark Levy 139 From the Pages of 11 The Mediated Performance La Mamelle and ART COM Susannah Magers 82 IMPROVIDEO: Interactive Broadcast Conceived as the New Direction of Subscription Television Interviews Anthology: 1975–1984 Gregory McKenna 188 From the White Space to the Airwaves: 17 La Mamelle: From the Pages: 87 Performing Post-Performancist An Interview with Nancy Frank Lifting Some Words: Some History Performance Part I Michele Fiedler David Highsmith Carl Loeffler 192 Organizational Memory: An Interview 19 Video Art and the Ultimate Cliché 92 Performing Post-Performancist with Darlene Tong Darryl Sapien Performance Part II The Curatorial Practice Class Carl Loeffler 21 Eleanor Antin: An interview by mail Mary Stofflet 96 Performing Post-Performancist 196 Contributor Biographies Performance Part III 25 Tom Marioni, Director of the Carl Loeffler 199 Index of Images Museum of Conceptual Art (MOCA), San Francisco, in Conversation 100 Performing Post-Performancist Carl Loeffler Performance or The Televisionist Performing Televisionism 33 Chronology Carl Loeffler Linda Montano 104 Talking Back to Television 35 An Identity Transfer with Joseph Beuys Anne Milne Clive Robertson -

Hold Still: Looking at Photorealism RICHARD KALINA

Hold Still: Looking at Photorealism RICHARD KALINA 11 From Lens to Eye to Hand: Photorealism 1969 to Today presents nearly fifty years of paintings and watercolors by key Photorealist taken care of by projecting and tracing a photograph on the canvas, and the actual painting consists of varying degrees (depending artists, and provides an opportunity to reexamine the movement’s methodology and underlying structure. Although Photorealism on the artist) of standard under- and overpainting, using the photograph as a color reference. The abundance of detail and incident, can certainly be seen in connection to the history, style, and semiotics of modern representational painting (and to a lesser extent while reinforcing the impression of demanding skill, actually makes things easier for the artist. Lots of small things yield interesting late-twentieth-century art photography), it is worth noting that those ties are scarcely referred to in the work itself. Photorealism is textures—details reinforce neighboring details and cancel out technical problems. It is the larger, less inflected areas (like skies) that contained, compressed, and seamless, intent on the creation of an ostensibly logical, self-evident reality, a visual text that relates are more trouble, and where the most skilled practitioners shine. almost entirely to its own premises: the stressed interplay between the depiction of a slice of unremarkable three-dimensional reality While the majority of Photorealist paintings look extremely dense and seem similarly constructed from the ground up, that similarity is and the meticulous hand-painted reproduction of a two-dimensional photograph. Each Photorealist painting is a single, unambiguous, most evident either at a normal viewing distance, where the image snaps together, or in the reducing glass of photographic reproduction. -

Visions of the Davis Art Center

Lost and Found: Visions of the Davis Art Center Permanent Collection 1967-1992 October 8 – November 19, 2010 This page is intentionally blank 2 Lost and Found: Visions of the Davis Art Center In the fall of 2008, as the Davis Art Center began preparing for its 50th anniversary, a few curious board members began to research the history of a permanent collection dating back to the founding of the Davis Art Center in the 1960s. They quickly recognized that this collection, which had been hidden away for decades, was a veritable treasure trove of late 20th century Northern California art. It’s been 27 years since the permanent collection was last exhibited to the public. Lost and Found: Visions of the Davis Art Center brings these treasures to light. Between 1967 and 1992 the Davis Art Center assembled a collection of 148 artworks by 92 artists. Included in the collection are ceramics, paintings, drawings, lithographs, photographs, mixed media, woodblocks, and textiles. Many of the artists represented in the collection were on the cutting edge of their time and several have become legends of the art world. Lost and Found: Visions of the Davis Art Center consists of 54 works by 34 artists ranging from the funky and figurative to the quiet and conceptual. This exhibit showcases the artistic legacy of Northern California and the prescient vision of the Davis Art Center’s original permanent collection committee, a group of volunteers who shared a passion for art and a sharp eye for artistic talent. Through their tireless efforts acquiring works by artists who were relatively unknown at the time, the committee created what would become an impressive collection that reveals Davis’ role as a major player in a significant art historical period. -

11757.Intro.Pdf

Introduction I first met David Ireland in 1975. it was during that year that he purchased his 500 Capp street home in san francisco’s Mission District while i was simulta- neously at work renovating a commercial building in the city’s south of Market street district. Cheap real estate was abundant at the time, and a year earlier i had purchased the Coast Casket Company while it was in its last throes of business. thereafter, artist Jim Pomeroy and i each set to building out our respective live- in studio lofts on the old brick warehouse’s second floor, while below us the first floor of 80 langton street was also being renovated and soon opened as a vibrant alternative artists’ space that we and others helped to cofound. it later became new langton arts, which remained a vital space for exhibitions and events until it closed in 2009. Many of us artists living in san francisco during the 1970s possessed the tools and hand skills needed to undertake such renovation projects, most of which were correctly wired, plumbed, and constructed, but seldom undertaken with proper building permits. nobody had much money back then, and hence we often relied on each other for good advice and swaps of labor and materials. i remember becoming aware of David ireland’s considerable skills with tools and materials when tom Marioni commissioned him to sensitively restore a wall that had been altered during a performance within the Museum of Conceptual art (MoCa). tom had opened MoCa in 1970, and it was yet another young south of Market arts institution that was greatly enlivening a growing community of artists who were busily working across multiple creative disciplines and media with utter comfort and curiosity. -

WINTER 2014.Indd

The Print Club of New York Inc Winter 2014 President’s Greeting Mona Rubin t’s hard to believe that I am entering my fourth year as President. The beginning of a new year is a good I time to reflect on highlights from the past twelve months and to focus on how to make this new season a meaningful one for our members. One development that stands out for me is how nation- ally connected the Print Club has become. I receive mail- ings from printers and publishers all over the country, as far away as Seattle. We are pleased to welcome an impor- tant new member this year, Sue Oehme, who has pub- lished prints by several of our Presentation Print artists out of her studio in Colorado – Oehme Graphics. Although she is a distance away, I am certain she will make important contributions to the club with her wealth Our Prints Ready to Ship. PHOTO COURTESY OF ROBERT of knowledge and interesting group of artists. BLACKBURN PRINTMAKING WORKSHOP Kay Deaux has continued to provide us with extraordi- nary events, which cover a broad range of styles and inter- this in mind if any of you see an interesting print show or ests. It saddens me that more members do not take have an idea you would like to share. Gillian is always advantage of these opportunities, especially since they are available to discuss writing an article. (Contact her at an integral benefit of membership. Kay is planning to send [email protected].) a survey in the next few months to try to understand what Our two newest Board Members, Kimberly Henrikson modifications may increase attendance. -

Tom Marioni Papers, 1970-2017, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Tom Marioni Papers, 1970-2017, in the Archives of American Art Christopher DeMairo The processing of this collection received Federal support from the Smithsonian Collections Care and Preservation Fund, administered by the National Collections Program and the Smithsonian Collections Advisory Committee. 2021 March 2 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series 1: Address and Appointment Books, circa 1970-2011.................................. 4 Series 2: Guest Books, 1991-2017......................................................................... -

Bechtle Robert

LOUIS K. MEISEL GALLERY ROBERT BECHTLE Biography Updated: 1/15/20 BORN 1932 San Francisco, CA EDUCATION 1958 California College of Arts and Crafts, Oakland, CA; M.F.A. University of California, Berkeley, CA 1954 California College of Arts and Crafts, Oakland, CA; B.A. SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2018 Gladstone Gallery, New York, NY Anthony Meier Fine Arts, San Francisco, CA 2014 Gladstone Gallery, New York, NY 2010 Gallery Paule Anglim, San Francisco, CA 2007 Crown Point Press, San Francisco, CA Robert Bechtle: Plein Air 1986-1999, Gallery Paule Anglim, San Francisco, CA 2006 Gladstone Gallery, New York, NY Robert Bechtle: A Retrospective, Modern Art Museum, Fort Worth, TX, Jun. 26 – Aug. 28 Robert Bechtle: A Retrospective, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., Mar. 4 – Jun. 4 2005 Robert Bechtle: A Retrospective, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, CA, Feb. 12 – Jun. 5 Gallery Paule Anglim, San Francisco, CA 2002 Gallery Paule Anglim, San Francisco, CA 2001 O.K. Harris Works of Art, New York, NY 141 Prince Street, New York, NY 10012 | T: 212 677 1340 | F: 212 533 7340 | E: [email protected] LOUIS K. MEISEL GALLERY 2000 Centric 58: Robert Bechtle-California Classic, University Art Museum, California State University, Long Beach, CA Gallery Paule Anglim, San Francisco, CA 1997 Watercolors, O.K. Harris Works of Art, New York, NY 1996 Gallery Paule Anglim, San Francisco, CA O.K. Harris Works of Art, New York, NY 1992 O.K. Harris Works of Art, New York, NY 1991 Daniel Weinberg Gallery, Santa Monica, CA Gallery Paule Anglim, San Francisco, CA Robert Bechtle: New York, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, CA 1987 O.K. -

W E S T C O a S T a R T S a N D C U L T U

free SWEST COAST ARTS AND CULTUREFAQ Jay DeFeo Jens Hoffmann Kathan Brown Bay Area Latino Arts Part 1: Enrique Chagoya - MENA Report Part 1: Istanbul Biennial with Jens Hoffmann - Scales Fall From My Eyes: Bay Area Beat Generation Visual Art as told to Paul Karlstrom - Peter Selz - Crown Point Press: Kathan Brown SFAQ Artist Spread - Paulson Bott Press - Collectors Corner: Peter Kirkeby Flop Box Zine Reviews - Bay Area Event Calendar: August, September, October West Coast Residency Listing SAN FRANCISCO ARTS QUARTERLY ISSUE.6 ROBERT BECHTLE A NEW SOFT GROUND ETCHING Brochure available Three Houses on Pennsylvania Avenue, 2011. 30½ x 39", edition 40. CROWN POINT PRESS 20 Hawthorne Street San Francisco, CA 94105 www.crownpoint.com 415.974.6273 3IGNUPFOROURE NEWSLETTERATWWWFLAXARTCOM ,IKEUSON&ACEBOOK &OLLOWUSON4WITTER 3IGNUPFOROURE NEWSLETTERATWWWFLAXARTCOM ,IKEUSON&ACEBOOK &OLLOWUSON4WITTER berman_sf_quarterly_final.pdf The Sixth Los Angeles International Contemporary Art Fair September 30 - October 2, 2011 J.W. Marriott Ritz Carlton www.artla.net \ 323.965.1000 Bruce of L.A. B. Elliott, 1954 Collection of John Sonsini Ceramics Annual of America 2011 October 7-9, 2011 ART FAIR SAN FRANCISCO FORT MASON | FESTIVAL PAVILION DECEMBER 1 - 4, 2011 1530 Collins Avenue (south of Lincoln Road), Miami Beach $48$$570,$0,D&20 VIP Preview Opening November 30, 2011 For more information contact: Public Hours December 1- 4, 2011 [email protected] 1.877.459.9CAA www.ceramicsannual.org “The best hotel art fair in the world.” DECEMBER 1 - 4, 2011 1530 Collins Avenue (south of Lincoln Road), Miami Beach $48$$570,$0,D&20 VIP Preview Opening November 30, 2011 Public Hours December 1- 4, 2011 “The best hotel art fair in the world.” Lucas Soi ìWe Bought The Seagram Buildingî October 6th-27th For all your art supply needs, pick Blick.