Atlanta Braves Clippings Friday, September 18, 2020 Braves.Com

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NCAA Division I Baseball Records

Division I Baseball Records Individual Records .................................................................. 2 Individual Leaders .................................................................. 4 Annual Individual Champions .......................................... 14 Team Records ........................................................................... 22 Team Leaders ............................................................................ 24 Annual Team Champions .................................................... 32 All-Time Winningest Teams ................................................ 38 Collegiate Baseball Division I Final Polls ....................... 42 Baseball America Division I Final Polls ........................... 45 USA Today Baseball Weekly/ESPN/ American Baseball Coaches Association Division I Final Polls ............................................................ 46 National Collegiate Baseball Writers Association Division I Final Polls ............................................................ 48 Statistical Trends ...................................................................... 49 No-Hitters and Perfect Games by Year .......................... 50 2 NCAA BASEBALL DIVISION I RECORDS THROUGH 2011 Official NCAA Division I baseball records began Season Career with the 1957 season and are based on informa- 39—Jason Krizan, Dallas Baptist, 2011 (62 games) 346—Jeff Ledbetter, Florida St., 1979-82 (262 games) tion submitted to the NCAA statistics service by Career RUNS BATTED IN PER GAME institutions -

Atlanta Braves Clippings Monday, September 21, 2020 Braves.Com

Atlanta Braves Clippings Monday, September 21, 2020 Braves.com Wright baffles Mets in 6 1/3-inning, 1-hit gem By Mark Bowman Ronald Acuña Jr. was bound to right himself before the postseason arrived. But the fact Kyle Wright has also started the regular season’s home stretch on a good note gives the Braves even more reason to be excited about what October might bring. Acuña’s solo homer provided all of the necessary support for Wright, who constructed a career-best start in the Braves’ 7-0 win over the Mets on Sunday afternoon at Citi Field. The right-hander’s confidence has grown significantly as he’s used his past two starts to show he has the potential to lessen concerns about the postseason rotation. “He’s been tremendous,” said catcher Travis d’Arnaud, who hit a two-run double in the eighth inning. “His demeanor on the mound and his demeanor in between innings, he’s been carrying himself really well. He’s just been attacking guys.” The Braves’ magic number to clinch a third consecutive National League East title has been reduced to six with seven games remaining, four of which will be played against the second-place Marlins this week. Looking ahead to the postseason, the Braves’ rotation will likely include Max Fried, Ian Anderson, Cole Hamels and Wright, who had essentially been a candidate by default before he produced two of the strongest starts of his young career over the past eight days. Wright earned his first career win with six strong innings at Nationals Park last weekend. -

Trevor Bauer

TREVOR BAUER’S CAREER APPEARANCES Trevor Bauer (47) 2009 – Freshman (9-3, 2.99 ERA, 20 games, 10 starts) JUNIOR – RHP – 6-2, 185 – R/R Date Opponent IP H R ER BB SO W/L SV ERA Valencia, Calif. (Hart HS) 2/21 UC Davis* 1.0 0 0 0 0 2 --- 1 0.00 2/22 UC Davis* 4.1 7 3 3 2 6 L 0 5.06 CAREER ACCOLADES 2/27 vs. Rice* 2.2 3 2 1 4 3 L 0 4.50 • 2011 National Player of the Year, Collegiate Baseball • 2011 Pac-10 Pitcher of the Year 3/1 UC Irvine* 2.1 1 0 0 0 0 --- 0 3.48 • 2011, 2010, 2009 All-Pac-10 selection 3/3 Pepperdine* 1.1 1 1 1 1 2 L 0 3.86 • 2010 Baseball America All-America (second team) 3/7 at Oklahoma* 0.2 1 0 0 0 0 --- 0 3.65 • 2010 Collegiate Baseball All-America (second team) 3/11 San Diego State 6.0 2 1 1 3 4 --- 0 2.95 • 2009 Louisville Slugger Freshman Pitcher of the Year 3/11 at East Carolina* 3.2 2 0 0 0 5 W 0 2.45 • 2009 Collegiate Baseball Freshman All-America 3/21 at USC* 4.0 4 2 1 0 3 --- 1 2.42 • 2009 NCBWA Freshman All-America (first team) 3/25 at Pepperdine 8.0 6 2 2 1 8 W 0 2.38 • 2009 Pac-10 Freshman of the Year 3/29 Arizona* 5.1 4 0 0 1 4 W 0 2.06 • Posted a 34-8 career record (32-5 as a starter) 4/3 at Washington State* 0.1 1 2 1 0 0 --- 0 2.27 • 1st on UCLA’s career strikeouts list (460) 4/5 at Washington State 6.2 9 4 4 0 7 W 0 2.72 • 1st on UCLA’s career wins list (34) 4/10 at Stanford 6.0 8 5 4 0 5 W 0 3.10 • 1st on UCLA’s career innings list (373.1) 4/18 Washington 9.0 1 0 0 2 9 W 0 2.64 • 2nd on Pac-10’s career strikeouts list (460) 4/25 Oregon State 8.0 7 2 2 1 7 W 0 2.60 • 2nd on UCLA’s career complete games list (15) 5/2 at Oregon 9.0 6 2 2 4 4 W 0 2.53 • 8th on UCLA’s career ERA list (2.36) • 1st on Pac-10’s single-season strikeouts list (203 in 2011) 5/9 California 9.0 8 4 4 1 10 W 0 2.68 • 8th on Pac-10’s single-season strikeouts list (165 in 2010) 5/16 Cal State Fullerton 9.0 8 5 5 2 8 --- 0 2.90 • 1st on UCLA’s single-season strikeouts list (203 in 2011) 5/23 at Arizona State 9.0 6 4 4 5 5 W 0 2.99 • 2nd on UCLA’s single-season strikeouts list (165 in 2010) TOTAL 20 app. -

2017 Information & Record Book

2017 INFORMATION & RECORD BOOK OWNERSHIP OF THE CLEVELAND INDIANS Paul J. Dolan John Sherman Owner/Chairman/Chief Executive Of¿ cer Vice Chairman The Dolan family's ownership of the Cleveland Indians enters its 18th season in 2017, while John Sherman was announced as Vice Chairman and minority ownership partner of the Paul Dolan begins his ¿ fth campaign as the primary control person of the franchise after Cleveland Indians on August 19, 2016. being formally approved by Major League Baseball on Jan. 10, 2013. Paul continues to A long-time entrepreneur and philanthropist, Sherman has been responsible for establishing serve as Chairman and Chief Executive Of¿ cer of the Indians, roles that he accepted prior two successful businesses in Kansas City, Missouri and has provided extensive charitable to the 2011 season. He began as Vice President, General Counsel of the Indians upon support throughout surrounding communities. joining the organization in 2000 and later served as the club's President from 2004-10. His ¿ rst startup, LPG Services Group, grew rapidly and merged with Dynegy (NYSE:DYN) Paul was born and raised in nearby Chardon, Ohio where he attended high school at in 1996. Sherman later founded Inergy L.P., which went public in 2001. He led Inergy Gilmour Academy in Gates Mills. He graduated with a B.A. degree from St. Lawrence through a period of tremendous growth, merging it with Crestwood Holdings in 2013, University in 1980 and received his Juris Doctorate from the University of Notre Dame’s and continues to serve on the board of [now] Crestwood Equity Partners (NYSE:CEQP). -

Baltimore Orioles Game Notes

BALTIMORE ORIOLES GAME NOTES ORIOLE PARK AT CAMDEN YARDS • 333 WEST CAMDEN STREET • BALTIMORE, MD 21201 MONDAY, AUGUST 20, 2018 • GAME #125 • ROAD GAME #64 BALTIMORE ORIOLES (37-87) at TORONTO BLUE JAYS (55-69) RHP Andrew Cashner (4-10, 4.71) vs. RHP Marco Estrada (6-9, 4.87) CEDRIC THE ENTERTAINER: OF Cedric Mullins went 2-for-3 on Sunday at Cleveland and hit his first career home run Saturday...Since I’VE GOT YOUR BACK making his Major League debut on August 10, he is batting .387 (12-for-31) and six of his 12 hits are extra-base hits...Mullins has five Lowest inherited runners scored percentage in doubles through nine career games...He is the first Orioles batter with at least five doubles through nine career games since current Orioles the American League (by team): assistant hitting coach Howie Clark notched five doubles in 2002...Since making his debut on August 10, Mullins’ .387 batting average 1. Los Angeles-AL 20.6% (43-of-209) leads AL rookies and ranks second in the majors among rookies behind Atlanta’s Ronald Acuña, Jr. (.450)...His five doubles since August 2. Houston 24.6% (32-of-130) 10 are tied for second-most in the majors among rookies. 3. Cleveland 27.0% (48-for-178) 4. Boston 28.2% (37-of-131) BREAKING NEWS: The Orioles rank among league leaders in several major offensive categories since the All-Star break, including 5. BALTIMORE 29.1% (67-of-230) ranking third in the majors in batting average at .276 (257-for-931)...They have recorded 257 hits in 26 games since the All-Star break, 6. -

UPCOMING SCHEDULE and PROBABLE STARTING PITCHERS DATE OPPONENT TIME TV ORIOLES STARTER OPPONENT STARTER June 12 at Tampa Bay 4:10 P.M

FRIDAY, JUNE 11, 2021 • GAME #62 • ROAD GAME #30 BALTIMORE ORIOLES (22-39) at TAMPA BAY RAYS (39-24) LHP Keegan Akin (0-0, 3.60) vs. LHP Ryan Yarbrough (3-3, 3.95) O’s SEASON BREAKDOWN KING OF THE CASTLE: INF/OF Ryan Mountcastle has driven in at least one run in eight- HITTING IT OFF Overall 22-39 straight games, the longest streak in the majors this season and the longest streak by a rookie American League Hit Leaders: Home 11-21 in club history (since 1954)...He is the first Oriole with an eight-game RBI streak since Anthony No. 1) CEDRIC MULLINS, BAL 76 hits Road 11-18 Santander did so from August 6-14, 2020; club record is 11-straight by Doug DeCinces (Sep- No. 2) Xander Bogaerts, BOS 73 hits Day 9-18 tember 22, 1978 - April 6, 1979) and the club record for a single-season is 10-straight by Reggie Isiah Kiner-Falefa, TEX 73 hits Night 13-21 Jackson (July 11-23, 1976)...The MLB record for consecutive games with an RBI by a rookie is No. 4) Vladimir Guerrero, Jr., TOR 70 hits Current Streak L1 10...Mountcastle has hit safely in each of these eight games, slashing .394/.412/.848 (13-for-33) Yuli Gurriel, HOU 70 hits Last 5 Games 3-2 with three doubles, four home runs, seven runs scored, and 12 RBI. Marcus Semien, TOR 70 hits Last 10 Games 5-5 Mountcastle’s eight-game hitting streak is the longest of his career and tied for the April 12-14 fourth-longest active hitting streak in the American League. -

2021 Topps Inception Checklist Baseball

2021 Topps Inception Baseball Checklist Player Set Card # Team Print Run Anthony Rendon Auto - Dawn of Greatness DOGA-AR Angels 36 Anthony Rendon Auto - Short Print SPIA-JS Angels 10 Jahmai Jones Auto Relic - Auto Button APC-JJ Angels 6 Jahmai Jones Auto Relic - Auto Logo APC-JJ Angels 1 Jahmai Jones Auto Relic - Auto Patch APC-JJ Angels Unknown Jo Adell Auto - Base Rookie and Future Phenom RESA-JA Angels Base + 375 Jo Adell Auto Relic - Auto Button APC-JA Angels 6 Jo Adell Auto Relic - Auto Jumbo Hat AHP-JA Angels 15 Jo Adell Auto Relic - Auto Jumbo Logo AJP-JA Angels 1 Jo Adell Auto Relic - Auto Jumbo Patch AJP-JA Angels Base + 85 Jo Adell Auto Relic - Auto Logo APC-JA Angels 1 Jo Adell Auto Relic - Auto Patch APC-JA Angels Unknown Jo Adell Auto Relic - Dual Player Auto Relic Book DARB-AM Angels 4 Jo Adell Auto Relic - Game Socks Auto AGSR-JA Angels 4 Jo Adell Auto Relic - Gameday Book GGAR-JA Angels 6 Jo Adell Auto Relic - Laundry Tag Auto Book ALTB-JA Angels 1 Jo Adell Auto Relic - Letter Patch Auto Book ALBC-JA Angels 2 Jo Adell Auto Relic - MLB Logo Patch Auto Book MLBB-JA Angels 1 Jo Adell Auto Relic - Team Logo Auto Book ATLP-JA Angels 2 Jo Adell Auto -Silver Signings SS-JA Angels Base + 26 Mike Trout Auto - Short Print SPIA-MT Angels 10 Mike Trout Auto Relic - Letter Patch Auto Book ALBC-MT Angels 2 Mike Trout Auto Relic - MLB Logo Patch Auto Book MLBB-MT Angels 1 Anthony Rendon Base 14 Angels Unknown Jo Adell Base Rookie 20 Angels Unknown Mike Trout Base 60 Angels Unknown Shohei Ohtani Base 78 Angels Unknown GroupBreakChecklists.com -

2019 TBL Annual 3 the TBL Baseball Annual

The TBL Baseball Annual A publication of the Transcontinental Baseball League The Rebuild 2019 Edition Walter H. Hunt All 24 Teams Analyzed Robert Jordan Using the T.Q. System Mark H. Bloom The TBL Baseball Annual A publication of the Transcontinental Baseball League by Walter H. Hunt Robert Jordan Mark H. Bloom with contributions from TBL’s managers and extra help from: Joe Auletta Paul Montague Craig Musselman Rich Meyer Copyright © 2019 Walter H. Hunt. This book was produced using a Macintosh with Adobe InDesign and Adobe Photoshop. I can be reached by mail at 3306 Maplebrook Road, Bellingham, MA 02019 or by e-mail at [email protected]. The 2019 TBL Annual 3 the TBL baseball annual Welcome to the 2019 TBL Baseball Annual. This is the twenty-fifth year of the Annual in the book format. This year we’re looking at the rebuild – certainly one of the most discussed topics in every TBL offseason. We’ve assembled a collection of insightful articles, including our lead from Robert, Joe Auletta’s deconstruction of the concept of rebuild, a Rich Meyer discussion of unbuilding, and a scholarly discussion of bullpens from Paul Montague. The staff would also like to thank Craig Musselman and Joe Auletta for help with Year in Review articles. Our usual collection of team and division articles, and most of our usual features are here. Once again, we’re glad to present the best of TBL, our great APBA league, now old enough to run for President. Enjoy the Annual and enjoy the season. Walter, Robert, Mark May, 2019 The T.Q. -

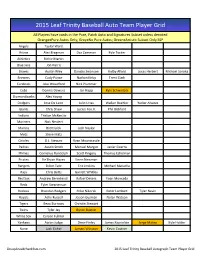

2015 Leaf Trinity Baseball Auto Team Player Grid

2015 Leaf Trinity Baseball Auto Team Player Grid All Players have cards in the Pure, Patch Auto and Signatures Subset unless denoted Orange=Pure Autos Only; Grey=No Pure Autos; Green=Artistic Subset Only SSP Angels Taylor Ward Astros Alex Bregman Daz Cameron Kyle Tucker Athletics Richie Martin Blue Jays Jon Harris Braves Austin Riley Dansby Swanson Kolby Allard Lucas Herbert Michael Soroka Brewers Cody Ponce Nathan Kirby Trent Clark Cardinals Jake Woodford Nick Plummer Cubs Donnie Dewees Ian Happ Kyle Schwarber Diamondbacks Alex Young Dodgers Jose De Leon Julio Urias Walker Buehler Yadier Alvarez Giants Chris Shaw Lucius Fox Jr. Phil Bickford Indians Triston McKenzie Mariners Nick Neidert Marlins Brett Lilek Josh Naylor Mets Steve Matz Orioles D.J. Stewart Ryan Mountcastle Padres Austin Smith Manuel Margot Javier Guerra Phillies Cornelius Randolph Scott Kingery Thomas Eshelman Pirates Ke'Bryan Hayes Kevin Newman Rangers Dillon Tate Eric Jenkins Michael Matuella Rays Chris Betts Garrett Whitley Red Sox Andrew Benintendi Rafael Devers Yoan Moncada Reds Tyler Stephenson Rockies Brendan Rodgers Mike Nikorak Peter Lambert Tyler Nevin Royals Ashe Russell Jeison Guzman Nolan Watson Tigers Beau Burrows Christin Stewart Twins Tyler Jay Byron Buxton White Sox Carson Fulmer Yankees Aaron Judge Drew Finley James Kaprielian Jorge Mateo Kyle Holder None Jack Eichel Jameis Winston Kevin Costner Groupbreakchecklists.com 2015 Leaf Trinity Baseball Autograph Team Player Grid. -

SUNDAY, MAY 2, 2021 • GAME #28 • ROAD GAME #14 BALTIMORE ORIOLES (13-14) at OAKLAND ATHLETICS (16-13) LHP Bruce Zimmermann (1-3, 5.33) Vs

SUNDAY, MAY 2, 2021 • GAME #28 • ROAD GAME #14 BALTIMORE ORIOLES (13-14) at OAKLAND ATHLETICS (16-13) LHP Bruce Zimmermann (1-3, 5.33) vs. LHP Sean Manaea (3-1, 2.83) O’s SEASON BREAKDOWN LIFE ON THE ROAD: The O’s defeated the A’s for the second-straight day, capturing their third road HITTING IT OFF Overall 13-14 series win of the season; the O’s have yet to win a series at home...The O’s have gone 9-4 on the Major League Hit Leaders: Home 4-10 road for a .692 winning percentage, the second-highest in the AL and tied for third-best in the majors. No. 1) CEDRIC MULLINS, BAL 35 hits Road 9-4 The O’s have posted a team ERA of 2.93 (38 ER/116.2 IP) in their 13 road games, the J.D. Martinez, BOS 35 hits Day 6-6 lowest road ERA in the majors. No. 3) Xander Bogaerts, BOS 34 hits Night 7-8 The O’s have averaged 4.1 runs per game on the road and 3.5 at home; they have a Yermin Mercedes, CWS 34 hits Current Streak W3 +13 run differential on the road and a -22 run differential at home. No. 5) Tommy Edman, STL 33 hits Last 5 Games 3-2 The O’s are looking for their second road sweep of the season (4/2-4 at BOS). Mike Trout, LAA 33 hits Last 10 Games 5-5 With a win today, the O’s would reach the .500 mark for the first time since being 4-4.. -

Tribe's Eye Remains on WS Prize in 2018 by Jordan

Tribe's eye remains on WS prize in 2018 By Jordan Bastian MLB.com @MLBastian CLEVELAND -- When word began to spread that Carlos Santana had agreed to a free-agent contract with the Phillies, Indians catcher Yan Gomes fired off a text to his long-time teammate. Santana was well-liked inside Cleveland's clubhouse and productive on the field, but his departure does not damper the Tribe's expectations for 2018. "Guys are going to step up and pick up the roles of the guys that we lost," Gomes said recently. "We don't go into the offseason thinking there's some secret magic guy out there that's going to, boom, join us and next thing you know we're World Series champions. We have a good enough team. We don't need to panic. We believe that we do have a good enough team." The Indians were the American League champions two seasons ago with much of the same group that's still on the roster, and they are coming off a 102-win campaign that ended with an early October exit. Cleveland has also absorbed some losses this winter (Santana, plus relievers Bryan Shaw and Joe Smith), but it still fields a team capable of contending for a third straight AL Central crown. The offseason is not over, but the year 2017 is officially in the books. Here are some questions facing the Indians in 2018: 1. Can the rotation continue to carry the load? The Indians' rotation led baseball with 81 wins last season and paced the AL (second in MLB) with a 3.52 ERA. -

New Orleans Privateer Baseball

New Orleans Privateer Baseball 1984 NCAA Div I World Series • 1974 NCAA Div II World Series NCAA Tournament • 73, 74, 77, 79, 80, 81, 82, 84, 85, 87, 88, 89, 96, 00, 07, 08 Conference Champions • 1978 & 2007 Sun Belt, 1989 American South Game 32-33 ● Southern Miss ● Apr. 9-10, 2013 New Orleans Privateers (5-26) vs.Southern Miss Golden Eagles (13-17) Tuesday, Apr. 9, 2013 • 6:30 p.m. Radio | WGSO 990 AM (Tues) Tuesday, Apr. 10, 2013 • 6 p.m. Live Stats/Video | UNOPrivateers.com.(Tues) &SouthernMiss.com (Weds) Twitter | @UNOPrivateers 2013 UNO Baseball Schedule/Results SERIES PREVIEW Date Opponent Result/Time • New Orleans won its third straight game at Barrow Stadium with a 1-0 victory 2.15 Southeast Missouri St L, 4-7 against Jackson State. UNO had played the previous 13 on the road, producing a 2.16 Southeast Missouri St L, 1-6. single win at Tulane. 2.17 Southeast Missouri St L, 2-11. • UNO will send Alex Smith (1-6, 4.74 ERA) to the mound on Tuesday followed by 2.19 at #3 Arkansas (G1) L, 0-14 2.19 at #3 Arkansas (G2) L, 0-3 fellow right-handed pitcher Seth Laigast (0-1, 18.90 ERA) - see page 4 on Laigast. 2.22 at South Alabama L, 6-29 • USM is 13-17 on the season and enters the week following a pair of wins against 2.24 at South Alabama (G1) L, 1-4 Tulane (6-2, 2-0) to claim 2 of 3 in a C-USA weekend series.