Introduction: Broken Narratives and 'Dis-Orientalism'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diyar Board of Directors

DiyarConsortium DiyarConsortium DiyarProductions Content Diyar Board of Directors Foreword 2 Bishop Dr. Munib Younan (Chair) Dar al-Kalima University College of Arts and Culture 6 Dr. Ghada Asfour-Najjar (Vice Chair) International Conferences 16 Mr. Jalal Odeh (Treasurer) The Model Adult Education Center 20 Dr. Versen Aghabekian (Secretary) Religion & State III 22 Mr. Albert Aghazarian The Civic Engagement Program 26 Mr. Ghassan Kasabreh Ajyal Elderly Care Program 30 Azwaj Program 32 Mr. Zahi Khouri Celebrate Recovery Project 34 Mr. Issa Kassis Diyar Academy for Children and Youth 35 Dr. Bernard Sabella Culture Program 41 Rev. Dr. Mitri Raheb (Founder & Authentic Tourism Program 44 President, ex officio) Gift Shop Sales for 2015 46 Diyar Publisher 48 Media Coverage 50 Construction Projects 53 1 In all of the construction projects, Diyar emphasized alternative itineraries into their schedules. When we aesthetics, cultural heritage, and green buildings. started in 1995, there were only 60 Palestinian tour FOREWORD Thanks to utilizing solar energy, Diyar was able in 2015 guides (out of a total of 4000 guides); all of them were to generate 40% of its energy consumption through over 60 years old and had received their license from solar. By 2020, we hope to reach zero-energy goal. the Jordanian government prior to 1967. Thanks to Dar Dear Friends, al-Kalima University College of Arts and Culture, today In all these years Diyar programs were highlighted in there are over 500 trained and accredited Palestinian ANNUAL REPORT 2015 ANNUALREPORT Salaam from Bethlehem. The year 2015 marked Diyar’s 20th anniversary. It was on many media outlets including the BBC, CNN, ABC, tour guides, who became Palestine’s ambassadors, September 28, 1995 that we inaugurated Dar Annadwa in the newly renovated CBS, HBO, ARD, ZDF, ORF, BR, al-Jazeera, Ma’an News sharing the Palestinian narrative with international crypt of Christmas Lutheran Church, as a place for worldwide encounter. -

1 Introduction the Palestine Liberation Organization Has Been Extensively Studied in the Social Sciences and Humanities Particul

This is the accepted version of an article that will be published by Duke University Press in Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East: https://www.dukeupress.edu/comparative-studies-of-south-asia-africa-and-the-middle- east/?viewby=journal Accepted version downloaded from SOAS Research Online: http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/24506/ PLO Cultural Activism: Mediating Liberation aesthetics in revolutionary contexts Dina Matar, Centre for Global Media and Communications, SOAS University of London [email protected] Abstract This paper addresses the PLO's cultural activism, in other words, its investment in diverse spheres of popular culture, at the beginning of the revolutionary period 1968- 1982 in its history. Drawing on archival research of the main spheres of the PLO's cultural output, it traces how the PLO strategized popular culture to enhance its image, create a new visibility for the Palestinians and mediate a Palestinian-centric liberation aesthetic rooted in real experiences of, and participation in, the Palestinian revolution. As such, the PLO's cultural activism combined an agential understanding of what it means to be Palestinian with popular armed struggle, language and image to conjure power in grassroots action, turn attention to the Palestinians themselves and evoke enduring affective identifications with the organization despite various setbacks and the passage of time. The argument is not intended to romanticize the role of the PLO or popular culture in a golden age of liberation politics. Rather it underlines -

Seized in Beirut the Plundered Archives of the Palestinian Cinema Institution and Cultural Arts Section

Seized in Beirut The Plundered Archives of the Palestinian Cinema Institution and Cultural Arts Section Rona Sela Abstract: One of the biggest acts of plunder by Israel was of a vast Palestinian film archive looted by Israeli military forces in Beirut in 1982. The films are managed under the repressive colonial control of the Israel Defense Forces Archive, which thus conceals many of them and information regarding their origin. This article documents my efforts to disclose the films and locate their institutions in Beirut, to chart their history, name their film-makers and open a discussion about returning them. It also provides a deeper understanding of colonial mechanisms of looting and truth production. I discuss the Third Palestine Cinema Movement and the various institutions that were part of the Palestinian revolution in the 1970s, with a focus on the Cultural Arts Section managed by Ismail Shammout. Keywords: art looting, colonial archives, Cultural Arts Section, Israel Defense Forces Archive (IDFA), Palestinian archives, Palestinian Cinema Institution, The United Media Israeli Colonial Mechanisms: Military Plunder, Looting, Censorship and Erasure of Palestinian History This article discusses Palestinian film archives plundered by Israeli forces in Beirut in 1982, held by the Israel Defense Forces Archive (IDFA) and cata- logued as ‘Seized Films from the PLO Archive in Beirut’ (Figure 1). The plun- dered archives contain historical documentation of daily life in Palestine before the Nakba (the Palestinian catastrophe and exile, 1948) that were gathered Anthropology of the Middle East, Vol. 12, No. 1, Summer 2017: 83–114 © Berghahn Books doi:10.3167/ame.2017.120107 • ISSN 1746-0719 (Print) • ISSN 1746-0727 (Online) 84 ← Rona Sela Figure 1: ‘IDF and Defense Establishment Archives. -

The Occupation of Palestinian Art: Maps, Land, Destruction and Concealment

The Occupation of Palestinian Art: Maps, Land, Destruction and Concealment Garrett Bailey A New Middle East?: Diagrams, Diagnosis and Power June 2016 1 Abstract Violence in the Middle East has been the focal point in news media. My paper has shifted the focus to forms of non-violent resistance as it pertains to Israel- Palestine. Palestinians have used art as a means of resistance before Israel declared itself a state in 1948. By focusing on Palestinian artists, I am able to show the ways in which art can reveal and counter Israeli Zionists rhetoric. Artists tear down the fallacies of Zionist propaganda through non-violent means. Resistance art is expressed in different forms, from maps, architecture and sculpture to film and graffiti. By examining Palestinian artists' work throughout the history of the Israeli-Palestine conflict, I am able to find out more about Israel's settlement building, border technology, pro-Israel lobbies, the tactics of the Israel Defense Force, and the censorship of Palestinian art. 2 Palestinians have engaged in non-violent resistance from the beginning of Israel's military occupation. Through an examination of maps, architecture, graffiti and film, I explore Israel's military tactics and their mechanisms of control. How does art shape the perceptions and realities of Israel/Palestine? Palestinian art is a necessary tool in exposing the oppression of the Israeli government and countering Zionist rhetoric. Zionism's purpose in the early 20th century was to find a homeland for the Jewish people living in the diaspora, proving the fall of the Ottoman Empire after World War One disastrous for the Palestinians. -

70 Years of Nakba: a Programme of 9 Palestinian Shorts

70 YEARS OF NAKBA: A PROGRAMME OF 9 PALESTINIAN SHORTS This programme was curated on the 70th Part 1 : History and exile anniversary of the Nakba (The Catastrophe), by the Palestine Strand of the Creative House | Ahmed Saleh |2011 Interruptions research project. The research For generations, a family lived in a spacious has aimed to explore how Palestinian and beautiful house. Guests were always filmmakers have used their cinema to give welcome to enjoy a pleasant stay. Until one voice to their history and experience. It has guest arrived with a different plan in mind. been concerned with self-representation (4mins) rather than with the work of solidarity filmmakers. www.creativeinterruptions.com Alyasiini | SaheraDirbas | 2012 Mahmad Alyasiini is a Palestinian survivor The programme makes use of the rich from Deir Yassin, west of Jerusalem. He collection of short films produced by a diverse recounts his life in the village before the group of creative practitioners living both Nakba and tells how he survived the massacre within the borders of historic Palestine and on April 1948. On 9 April 1948, a month outside it. It enables us to understand the before the establishment of the state of diversity of Palestinian experience from exile, Israel. 100 of the 600 residents in Deir Yassin to occupation, to living under siege as well as were killed and the rest forced to flee, an in refugee camps as stateless citizens. event which precipitated the occupants of Screening Palestinian shorts enables us to many other villages to flee in fear. (22 mins) appreciate the diversity of talent within Palestinian film production because many Glow of Memories | Ismail Shammout |1972 filmmakers find it difficult to secure funding Centring around an old Palestinian man who and support for their projects as stateless is the subject of Ismail Shammout’s painting people. -

A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts And

THE PALESTINE POSTER PROJECT ARCHIVES: ORIGINS, EVOLUTION, AND POTENTIAL A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Arab Studies By Daniel J. Walsh, B.S. Ed. Washington, DC December 19, 2011 THE PALESTINE POSTER PROJECT ARCHIVES: ORIGINS, EVOLUTION, AND POTENTIAL Daniel J. Walsh, B.S. Ed. Thesis Advisor: Rochelle A. Davis, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Focusing on the more than 6,000 posters now on view at the Palestine Poster Project Archives Website (“Website”), I will outline its evolution from a (failed) class project to online resource for viewing the poster art of the Palestinian-Zionist conflict (1897 – Present). I will discuss the major features of the Website, including Special Collections and Iconography and introduce the four Wellsprings of the Palestine poster: Zionist-Israeli (2,005 posters); Palestinian (2,514 posters); Arab/Muslim (331 posters); and International (1,195 posters). I will outline how I originally became aware of the Palestine poster genre and began building a personal collection that would eventually evolve into an archives (“Archives”). I will list some of the ways the Website is currently being used by artists and teachers and outline some of its planned features including as a clearinghouse for the display of new posters created in the context of Palestine poster contests. In my conclusion, I will argue that the Website of the Palestine Poster Project Archives opens a new “cultural position” (quoting Edward Said) from which Americans can dispassionately discuss the Palestinian-Zionist conflict. -

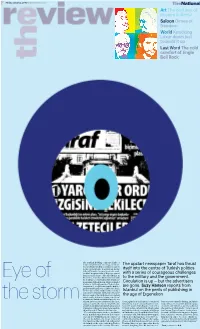

Artthe Civil War of Images in Beirut Saloondimes of Freedom

r Friday, January 2, 2009 www.thenational.ae The N!tion!l Art The civil war of images in Beirut Saloon Dimes of freedom World Knocking Luxor down just to build it up Last Word The cold comfort of Jingle Bell Rock The Turkish holding company Alarko, a major conglomerate of energy, construc- The upstart newspaper Taraf has thrust tion and tourism firms, resides in a pink former psychiatric hospital up in the itself into the centre of Turkish politics hills off Istanbul’s stunning shore road, on the European side of the city, across with a series of courageous challenges from a seaside dance club called Reina. In December, I went to Alarko to meet with to the military and the government. its chairman, a Turkish-Jewish business- Eye of man named Ishak Alaton. Alaton founded Circulation is up – but the advertisers Alarko in 1954 with another Turkish Jew, Uzeyir Garih, and the two ran the firm to- are gone. Suzy Hansen reports from gether until Garih was stabbed to death in 2001 by a young soldier while visiting a Istanbul on the perils of publishing in cemetery in Istanbul. At the time the mur- der was seen as the random act of a violent the age of Ergenekon psychopath, absent religious or political motivation. But the week that I went to see the storm Alaton, prosecutors reopened the case, sive Ergenekon indictment contained lent sense of comedic timing, and punc- suggesting that the murder was linked to allegations that the group had been con- tuated his sentences with dramatic paus- a mysterious ultranationalist gang called nected to a secret intelligence unit of the es and heavy syllables, as if he admired Ergenekon, whose intrigues have captivat- military police called JITEM, which some the oeuvre of Chris Rock. -

Palestinian Filmmakers … and Their (Latest) Works

PALESTINIAN FILMMAKERS … AND THEIR (LATEST) WORKS Hiam Abbass is an acclaimed Palestinian actress and film director who was born in Nazareth and grew up in a Palestinian village in the northern Galilee. Abbass has been featured in local as well as international films such as Haifa, The Gate of the Sun, Paradise Now, Munich, The Syrian Bride, Amreeka, The Visitor, Miral and Dégradé. She was nominated for Best Actress at the Israeli Film Academy Award for her performance in Eran Rikilis’ Lemon Tree. She has also written and directed the short films Le Pain, La Danse Eternelle, and Le Donne Della Vucciria. She has just completed the shooting of two new features, Rock the Casbah, and May in the Summer. Inheritance is her directorial debut. Inheritance 2012. Drama. 88 min A Palestinian family living in the north of the Galilee gathers to celebrate the wedding of one of their daughters, as war rages between Israel and Lebanon. The many family members symbolize a community struggling to maintain their identity, torn between modernity and tradition. When the youngest daughter, Hajar, returns on this occasion, she tells her father and patriarch Abu Majd, who has always encouraged her to learn and to discover the world, about the man she loves, an English art teacher. When the father falls into a coma and inches toward death, internal conflicts explode and the familial battles become as merciless as the outside war. Mohammed Abu Nasser (known as ‘Arab’) and his twin brother and partner in filmmaking Ahmed Abu Nasser (known as ‘Tarzan’) were born in Gaza in 1988. -

Place Attachment to the Palestinian Landscape: an Art-Based Visual Discourse Analysis

Place Attachment to the Palestinian Landscape: An Art-based Visual Discourse Analysis by Sima Kuhail A Thesis presented to The University of Guelph In partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Master of Landscape Architecture Guelph, Ontario, Canada © Sima Kuhail, May, 2020 ABSTRACT PLACE ATTACHMENT TO THE PALESTINIAN LANDSCAPE: AN ART-BASED VISUAL DISCOURSE ANALYSIS Sima Kuhail Advisor: University of Guelph, 2020 Larry Harder Place attachment is a significant affective, cognitive and emotional bond between people and places of significance. Displaced populations draw on their attachment to a place of origin to help them develop attachment to their new places. Currently eight million Palestinians are living in diaspora as they continue to be displaced. Art-based research is an emerging method in place attachment studies. This research aims to construct a visual art-based place attachment narrative of the Palestinian landscape to inform future landscape design interventions for Palestinian communities. A visual discourse analysis method is applied on the content of the “Intimate Terrains” Exhibition in Birzeit, Palestine (2019) to interpret place attachment to the Palestinian landscape as portrayed by Palestinian artists. This research, while specific to Palestine, can be generalized and can be utilized by landscape architects who intend to better understand the communities they design for and who intend to create meaningful places. Key words: Palestinian visual arts, art-based research, visual discourse analysis, landscape narrative, memory, home, belonging, identity. iii DEDICATION To my family iv ACKNOWLEGMENTS To my advisor Larry Harder, thank you for your guidance and mentorship throughout my journey in this degree. I have enjoyed our conversation throughout the past three years. -

The Responsibility to Palestinian Tatreez

Heritage is to Art as the Medium is to the Message: The Responsibility to Palestinian Tatreez Reem Farah Introduction When a viewer first sets eyes on a Jordan Nassar work, it is particularly gratifying. The aesthetic quality of the pastel, colour-blocked, textured tessellations can invoke a state like that induced by experiencing the golden hour or the golden ratio. At first glance, Nassar’s Palestinian landscape embroidery seems to reinforce the message of Palestinian embroidery or tatreez, tightly stitching Palestinian land and culture in an artful rebuttal against the erasure of Palestine. It seems to say: ‘The land is Palestine, Palestine is the land’. Jordan Nassar, In The Yellow Lake, 2020, cotton on cotton, exhibited at The Third Line Gallery, Dubai, photo courtesy of the author Tatreez is an indigenous embroidery practice and cultural art form that illustrates Palestinian land and life: the tradition of reading the bottom of the coffee cup embodied as a brown octagon, a diagonal culmination of lines depicting wheat, or an endless squiggle impersonating a row of snails. History tells us that couching is popular in Bethlehem because of the influence of the Byzantine Empire there.1 The predominance of amulets or triangle crescents among bedouin 1 Couching is a technique of surface embellishment embroidery Reem Farah, ‘Heritage is to Art as the Medium is to the Message: The Responsibility to Palestinian Tatreez’, Third Text Online, www.thirdtext.org/farah- tatreez1, 28 January 2021; published simultaneously in Third Text Forum: Decolonial Imaginaire, www.thirdtext.org/farah-tatreez 1 women is because they believed it repelled the evil eye; birds are showcased in Gaza and Haifa as they were especially visible in coastal towns during migration seasons.2 The variations and significations of motifs are specific according to the women who embroidered them, but they are also adaptive as they were worked on collectively. -

Nomination Form

International Memory of the World Register Liberation Graphics Collection of Palestine Posters 2014-13 1.0 Summary Documentary Heritage Being Nominated The Liberation Graphics Collection of Palestine Posters (Liberation Graphics Collection) comprises approximately 1,700 posters plus related paper ephemera, created by Palestinian and international artists in solidarity with the quest for Palestinian self-determination. These documents cover a critical time period in Palestinian history— the second half of the twentieth century, when Palestinians organized and asserted themselves under conditions of exile and occupation. The Palestine poster genre is unique in world art and a much-overlooked feature of Palestinian cultural heritage. Furthermore, the posters themselves are important repositories of primary data on Palestinian political and social history. They provide a unique lens through which audiences can gain insight into the aspirations, attitudes, and perspectives of the people involved in the events of contemporary Palestinian history, recorded as those events occurred. The Liberation Graphics Collection represents the core of the Palestine Poster Project Archives, http://www.palestineposterproject.org, which holds paper and/or digital images of more than 9,100 posters by some 1,800 artists from more than 50 countries. Inscription of the Liberation Graphics Collection is sought so that the posters can be conserved, organized, and prepared for acquisition by a Palestinian institution capable of maintaining them in perpetuity, ideally, in Palestine. 2.0 Nominators 2.1 Name of nominators (persons or organization) Dr. Salim Tamari; Dr. Rochelle Davis; Amer Shomali, M.A.; Dan Walsh, M.A.; Catherine Baker, M.Ed. 2.2 Relationship to the nominated documentary heritage Dr. -

Jerusalem: City of Dreams Tina Sherwell

Jerusalem: City of Dreams Tina Sherwell Introduction Sliman Mansour is one of the most prominent Palestinian artists working today who has created many memorable works that are part of the Palestinian collective memory and identity. His practice spans several decades in which he has distilled the experiences of Palestinians through the prism of his canvas, providing important reflection on the changing times of Palestinian history that he has lived through. Throughout his career he has created iconic images which have become a distinct part of Palestinian visual culture. Sliman Mansour was born in 1947 in Birzeit, Palestine. The fourth son in a The Camel of Hardships, 1973, oil on canvas, family of six, he lost his father at an early 70 x 105 cm. Source: artistʻs collection. age and moved to study at the Evangelical Jerusalem Quarterly 49 [ 43 ] Lutheran School in Bethlehem. From an early age he showed a keen interest in art, for which he found support and encouragement from one of his first art teachers, Felix Theis, from whom he learned about Renaissance and European art generally as well as receiving technical instruction. Mansour continued to pursue his interest in art through his teenage years, gaining confidence in this field in which he began to undertake portrait commissions from photographs, a genre that he would return to throughout his career, capturing the characters of individuals on his canvas as well as reflecting on his own changing identity over the years. Mansour is one of the few Palestinian artists who have an oeuvre of portrait painting, a result of his early training.