Landlord, Agent and Tenant in Later Nineteenth-Century Cheshire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beeston, Tiverton and Tilstone Fearnall Neighbourhood Plan Includes Policies That Seek to Steer and Guide Land-Use Planning Decisions in the Area

Beeston, Tiverton and Tilstone Fearnall Neighbourhood Development Plan 2017 - 2030 December 2017 1 | Page Contents 1.1 Foreword ................................................................................................................................. 5 1.2 Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................. 5 2. BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................ 6 2.1 Neighbourhood Plans ............................................................................................................... 6 2.2 A Neighbourhood Plan for Beeston, Tiverton and Tilstone Fearnall ........................................ 6 2.3 Planning Regulations ................................................................................................................ 8 3. BEESTON, TIVERTON AND TILSTONE FEARNALL .......................................................................... 8 3.1 A Brief History .......................................................................................................................... 8 3.2 Village Demographic .............................................................................................................. 10 3.3 The Villages’ Economy ........................................................................................................... 11 3.4 Community Facilities ............................................................................................................ -

A Magical Christmastime

Terms & Conditions Booking and payment terms Christmas Parties: £10.00 per person deposit required to secure your booking. Full payment required 6 weeks prior to the event. All payments are non refundable and non transferable. Festive Luncheons, Christmas Day and Boxing Day: £10.00 per person deposit required to secure your booking. Full payment 6 weeks prior to the event. £50 per room deposit will be required to secure all bedroom bookings, the remaining balance to be paid on departure. Credit card numbers will be required to secure all bedroom bookings. Preorders will be required for all meals. Peckforton Castle, Stonehouse Lane, Peckforton,Tarporley, Cheshire CW6 9TN A Magical Christmas Main Reception: 01829 260 930 Fax: 01829 261 230 Email: [email protected] www.peckfortoncastle.co.uk CHRISTMAS & NEW YEAR 2012Time HOW TO FIND US By Air Manchester or Liverpool Airport – both 40 minute drive. By Train Nearest stations are Crewe and Chester Christmas Booking Form – both 20 minute drive. By Road from M56 From M56 come off at Junction 10 following signs Name .................................................................................................................................................... to Whitchurch A49, follow this road for approx Address ............................................................................................................................................... A Magical Christmas 25 minutes; you will eventually come to traffic lights with the Red Fox Pub on your right hand ................................................................................................................................................................. -

1911 the Father of the Architect, John Douglas Senior, Was Born In

John Douglas 1830 – 1911 The father of the architect, John Douglas senior, was born in Northampton and his mother was born in Aldford, Cheshire. No records have been found to show where or when his parents married but we do know that John Douglas was born to John and Mary Douglas on April 11th 1830 at Park Cottage Sandiway near Northwich, Cheshire. Little is known of his early life but in the mid to late 1840s he became articled to the Lancaster architect E. G. Paley. In 1860 Douglas married Elizabeth Edmunds of Bangor Is-coed. They began married life in Abbey Square, Chester. Later they moved to Dee Banks at Great Boughton. They had five children but sadly only Colin and Sholto survived childhood. After the death of his wife in 1878, Douglas remained at the family home in Great Boughton before designing a new house overlooking the River Dee. This was known as both Walmoor Hill and Walmer Hill and was completed in 1896. On 23rd May 1911 John Douglas died, he was 81. He is buried in the family grave at Overleigh Cemetery, Chester. Examples of the Work of John Douglas The earliest known design by John Douglas dates from 1856 and was a garden ornament, no longer in existence, at Abbots Moss for Mrs. Cholmondeley. Hugh Lupus Grosvenor, first Duke of Westminster, saw this design and subsequently became Douglas’ patron paying him to design many buildings on his estates, the first being the Church of St. John the Baptist Aldford 1865-66. Other notable works include : 1860-61 south and southwest wings of Vale Royal Abbey for Hugh Cholmondley second Baron Delamere 1860-63 St. -

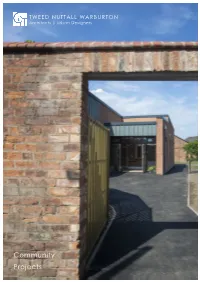

Community Projects

TWEED NUTTALL WARBURTON Architects | Urban Designers Community Projects 1 New Church Centre, Handbridge weed Nuttall Warburton has a long history of working on community projects. We believe community buildings should be designed to be flexible and accessible to all T users. The spaces should be welcoming and fit for purpose as function spaces ready for regular use and enjoyment as the center of a community. We also believe the buildings should be sustainable and provide the community with a legacy building for the years to come. We have a long association with the local community of Chester and surrounding villages. Our experienced team greatly value establishing a close Client/Architect relationship from the outset. We regularly engage with community groups and charities along with local authorities, heritage specialists and relevant consultants to ensure the process of producing a community building is as beneficial to the end users as is possible. We can provide feasibility studies to assist local community groups, charities and companies make important decisions about their community buildings. These studies can explore options to make the most of the existing spaces and with the use of clever extensions and interventions provide the centres with a new lease of life. We can also investigate opportunities for redevelopment and new purpose-built buildings. Church Halls and Community Centres Following the successful completion of several feasibility studies we have delivered a range of community centres and projects in Chester, Cheshire and North Wales. These have included: A £1.5m newbuild community centre incorporating three function spaces, a cafe and medical room for adjacent surgery all within the grounds of a Grade II* listed Church. -

Sample Pages

SAMPLE PAGES The 48-page, A4 handbook for Historic Chester, with text, photographs, maps and a reading list, is available for purchase, price £15.00 including postage and packing. Please send a cheque, payable to Mike Higginbottom, to – 63 Vivian Road Sheffield S5 6WJ Manchester’sManchester’s HeritageHeritage Best Western Queen Hotel, City Road, Chester, CH1 3AH 01244-305000 Friday September 18th-Sunday September 20th 2009 2 Introduction In many ways the most physically distinctive historic town in England, Chester is not quite what it seems. Its name reveals its Roman origin, and the concentration of later buildings in the historic core means that the revealed remains of Roman date are fragmentary but remarkable. Its whole raison d’être came from its position as the port at the bridging- point of the Dee and the gateway to North Wales, though there is little reminder now of its status as a sea-going port, except for the pleasure-craft on the Shropshire Union Canal, gliding below the town walls. Its famous Rows, the split-level medieval shopping streets, are without exact parallel, and their fabric dates from every century between the thirteenth and the present. It is a city fiercely proud of its conservation record, taking seriously the consultant’s comment that “Chester’s face is its fortune” to which someone at a meeting added “...but some of its teeth are missing,” – rightly so, for in the midst of much charm there are some appalling solecisms of modern development. Sir Nikolaus Pevsner and Edward Hubbard, in The Buildings of England: Cheshire (Penguin 1971), comment, “If one...tries to make up accounts, Chester is not a medieval, it is a Victorian city.” If so, it is a Victorian city that grew from an ancient port, with a Roman plan, its characteristic building-design conceived by the practical needs of medieval merchants, its strategic importance underlined by an earldom traditionally given to the Prince of Wales, a county town that became the seat of a Tudor bishopric, a key point in the transport arteries of the turnpike, canal and railway ages. -

The Elms Wrexham Road, Pulford Chester CH4

The Elms, Wrexham Road, Pulford, Chester The Elms double bedroom with built-in storage and en suite shower. Two further well-proportioned Wrexham Road, Pulford double bedrooms, one with a sink and the Chester CH4 9DG other with a sink and lavatory completes the accommodation. On the second floor is a further double bedroom. A detached family home with 0.88 acres in a sought-after location close to Outside Chester, with superb gardens The property is approached through twin wooden gates over a tarmacadam driveway Pulford 0.5 miles, Chester 4.6 miles, Wrexham offering parking for multiple vehicles and with 7.8 miles, Liverpool 25.8 miles, Manchester access to the detached double garage with a Airport 38.2 miles useful gardener’s cloakroom. Extending to some 0.88 acres, the well-maintained mature garden Sitting room | Drawing room | Dining room surrounding the property is laid mainly to level Kitchen | Breakfast room | Utility | Cloakroom lawn interspersed with well-stocked flowerbeds, Cellar/stores | 6 Bedrooms (2 en suite) | Garage numerous specimen shrubs and trees, a large Gardens | In all c 0.88 acres | EPC Rating E paved terrace, and a vegetable patch. The garden is screened by mature hedging, with The property views over surrounding pastureland. The Elms is an imposing period family home, in a Conservation Area, originally built c1795 Location then enlarged by John Douglas, principal The Elms sits on the northern fringes of Pulford architect for the Grosvenor Estate to provide a village, which lies to the south-west of Chester suitable residence for the Duke of Westminster’s on the England/Wales border. -

Vebraalto.Com

GREAT BUDWORTH GABLE END, SOUTHBANK CW9 6HG FLOOR PLAN (not to scale - for identification purposes only) £325,000 GREAT BUDWORTH GABLE END, SOUTHBANK ■ A Grade II listed cottage of character ■ Designed by local Architect, John Douglas 21/23 High Street, Northwich, Cheshire, CW9 5BY T: 01606 45514 E: [email protected] ■ In picturesque village of Great Budworth ■ With no ongoing chain to purchase GREAT BUDWORTH GABLE END, SOUTHBANK CW9 6HG Meller Braggins have particular pleasure in offering for sale the property known as 'Gable End' which is a distinctive and well modernised property with original leaded windows to the front elevation. With gas central heating the accommodation comprises living room, dining kitchen fitted with a range of integrated appliances and guest bedroom 2 with en-suite shower room. To the first floor there is an impressive and spacious master bedroom and a newly refurbished bathroom. Outside there is a private walled garden with the advantage of a southerly orientation. BEDROOM 1 16'8" x 14'10" (maximum) (5.08m x 4.52m (maximum)) stocked with a variety of plants and shrubs, trellis fencing, water The property is wonderfully situated in a quiet backwater of the KITCHEN DINING ROOM 16'3" (maximum) x 13'10" (4.95m (maximum) point, outside light. village and offers a lovely aspect facing the magnificent Grade 1 x 4.22m) listed St Mary and All Saints Church. The village of Great SERVICES Budworth is an idyllic location which is steeped in history and is All main services are connected. well documented in the Domesday Book. Within a short stroll is NOTE the George & Dragon public house, tennis and bowls club and a We must advise prospective purchasers that none of the fittings Church of England primary school. -

Buildings Open to View

6-9 September 2018 13-16 September 2018 BUILDINGS BUILDINGSOPEN TO OPENVIEW TO VIEW 0 2 Welcome to Heritage Open Days 2018 Heritage Open days celebrates our architecture and culture by allowing FREE access to interesting properties, many of which are not normally open to the public, as well as free tours, events, and other activities. It is organised by a partnership of Chester Civic Trust and Cheshire West and Chester Council, in association with other local societies. It would not be possible without the help of many building owners and local volunteers. Maps are available from Chester Visitor Information Centre and Northwich Information Centre. For the first time in the history of Heritage Open Days the event will take place nationally across two weekends in September the 6-9 and the 13-16. Our local Heritage Open Days team decided that to give everyone the opportunity to fully explore and discover the whole Cheshire West area Chester buildings would open on 6-9 September and Ellesmere Port & Mid Cheshire would open on 13-16 September. Some buildings/ events/tours were unable to do this and have opened their buildings on the other weekend so please check dates thoroughly to avoid disappointment. Events – Tours, Talks & Activities Booking is ESSENTIAL for the majority of HODs events as they have limited places. Please check booking procedures for each individual event you would like to attend. Children MUST be accompanied by adults. Join us If you share our interest in the heritage and future development of Chester we invite you to join Chester Civic Trust. -

Buildings Free to View

13-22 September 2019 BUILDINGS OPEN TO FREE BUILDINGSVIEW EVENTS FREE TO VIEW 0 2 Welcome to Heritage Open Days 2019 Heritage Open Days celebrates our architecture and culture by allowing FREE access to interesting properties, many of which are not normally open to the public, as well as free tours, events and activities. It is organised by a partnership of Chester Civic Trust and Cheshire West and Chester Council, in association with other local societies. It is only possible with the help of many building owners and local volunteers. Maps are available from Chester Visitor Information Centre and Northwich Information Centre. To celebrate their 25th anniversary, Heritage Open Days will take place nationally over ten days from 13 to 22 September 2019. In order to give everyone the opportunity to fully explore and discover the whole Cheshire West area, Chester buildings will mainly be open on 13 -16 September and Ellesmere Port and Mid Cheshire will mainly be open on 19-22 September. However they will also be open on other dates so please check details thoroughly to avoid disappointment. Events – Tours, Talks & Activities Booking is ESSENTIAL for the majority of HODs events as they have limited places. Please check booking procedures for each individual event you would like to attend. Children MUST be accompanied by adults. The theme for Heritage Opens Days this year is “People Power” and some of the events will be linked to this. Join us If you share our interest in the heritage and future development of Chester we invite you to join Chester Civic Trust. -

St John's Church, Sandiway

St John’s Church, Sandiway CONTENTS 3 Welcome to St John’s 4-5 About our parish 6-8 About our church 9-13 What we do now 14 What we want to do next 15 Who we are looking for “To worship God, and share his love with others.” Welcome to St John’s Thank you for enquiring about our vacancy. It's a very exciting time to be part of St John's. We are in the draft stage of a proposed major reordering project, and need a leader to help us to make decisions and take God's mission and ministry forward. St John's is a friendly welcoming church, aiming to be accessible and inclusive at the centre of our wider community. We hope you feel called to visit us. Our parish is fully supportive of women’s ministry. We are therefore seeking a vicar, male or female, who is enthusiastic about serving our community and who will enjoy playing an active part in the life of our village. Our vicar will be able to work in collaboration with our successful, wider ministry team and connect with people throughout the village, from the youngest to the oldest and lead us in continuing our journey forwards. p3 About our parish Cuddington and Sandiway today make up a wonderful village situated in mid Cheshire, a thriving place to live and work. The village is conveniently situated close to two local towns, approximately 4 miles west of Northwich and 3 miles north of Winsford. It has easy road and rail access to the cities of Chester, Manchester and Liverpool. -

Summer Day Trips

Summer 2016 Summer Day Trips Tel: 0151 357 4420 Email: [email protected] www.ectcharity.co.uk Welcome to our Summer Day Trips programme! ECT in Cheshire is part of ECT Charity, a leading transport charity in the UK which provides high quality, safe, friendly, accessible and affordable transport in local communities for those who find it difficult to use public transport. Our current services include: PlusBus – providing door-to-door journeys in Chester, Ellesmere Port and Neston. Group Transport – providing journeys to voluntary and community groups, with a professional driver. Evening Safe Transport – providing evening journeys between 5.30pm and 10.30pm Monday to Friday. Day Trips – helping individuals to visit places of interest, both locally and further afield. We are delighted to be offering our Day Trip services again over July, August and September 2016. We have some great trips scheduled over the summer and we hope there will be an outing of interest for everyone. Read on to find out more about our latest programme of events. We hope to see many of you on one or more of the outings! To find out more, visit us online at: www.ectcharity.co.uk Or call us on 0151 357 4420 3 Where can I go? Can I bring an escort? We are offering Day Trips to Cholmondeley Castle Gardens, Llandudno, Yes! If you need an escort to come with you, please let us know on the Tatton Park, Port Sunlight, Arley Hall & Gardens, Tweed Mill, Norton Priory booking form. Your escort will need to pay the same fare, so please include & Museum, Liverpool and Ice Cream Farm & Candle Workshop. -

Manchester, Liverpool & the PEAK DISTRICT

MotivAte, eDUCAte AnD reWArD Manchester, liverpool & THE PEAK DISTRICT roM UrBAn pleAsUres to rural treasures, this itinerary is loCAtion & ACCess all about contrasts. here your guests can discover two of The main gateway to North West england’s hippest cities, where sleek, contemporary style F is Manchester. rubs shoulders with historic reminders of industries past. X By road set your guests loose to walk in the footsteps of world- From London to Manchester: Approx. 3.5 hrs northwest/200 miles. famous names, from Manchester United to the Beatles. then whisk them off for a walk on the wild side in the spectacular j By air peak District. Nearest international airport: Manchester airport. From olympic cycling to rock climbing, there’s plenty of Alternative airports: opportunity to get active and be challenged. or they can Liverpool, Leeds-Bradford airports. simply relax on a historic train or in one of england’s o By train grandest treasure houses while soaking up the opulent From London-Euston to Manchester: 2 hrs. surroundings. Manchester Liverpool The Peak District Friendly energetic Manchester buzzes with the Best known as the home of the Beatles, Liverpool This dramatic National Park, the oldest in England, most happening of social scenes. is an important shipping port and cultural centre is a picturesque landscape of rocky crags, peat- which today is also a UNESCO World Heritage Site. covered moorlands and wooded limestone dales. Renowned for its passion for music, its world- famous football team and its endless nightlife, With its pubs and clubs and down-to-earth It’s a popular place for walking and cycling as the city rose to prominence in the 18th century humour, it’s a vibrant energetic city with a big well as other, more extreme sports.