Fanwork: Made from Something Different

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Infinite Diversity in Infinite Combinations: Portraits of Individuals with Disabilities in Star Trek

Infinite Diversity in Infinite Combinations: Portraits of Individuals With Disabilities in Star Trek Terry L. Shepherd An Article Published in TEACHING Exceptional Children Plus Volume 3, Issue 6, July 2007 Copyright © 2007 by the author. This work is licensed to the public under the Creative Commons Attribution License. Infinite Diversity in Infinite Combinations: Portraits of Individuals With Disabilities in Star Trek Terry L. Shepherd Abstract Weekly television series have more influence on American society than any other form of media, and with many of these series available on DVDs, television series are readily ac- cessible to most consumers. Studying television series provides a unique perspective on society’s view of individuals with disabilities and influences how teachers and peers view students with disabilities. Special education teachers can use select episodes to differenti- ate between the fact and fiction of portrayed individuals with disabilities with their stu- dents, and discuss acceptance of peers with disabilities. With its philosophy of infinite diversity in infinite combinations, Star Trek has portrayed a number of persons with dis- abilities over the last forty years. Examples of select episodes and implications for special education teachers for using Star Trek for instructional purposes through guided viewing are discussed. Keywords videotherapy, disabilities, television, bibliotherapy SUGGESTED CITATION: Shepherd, T.L. (2007). Infinite diversity in infinite combinations: Portraits of individuals with disabilities in Star Trek. TEACHING Exceptional Children Plus, 3(6) Article 1. Retrieved [date] from http://escholarship.bc.edu/education/tecplus/vol3/iss6/art1 "Families, societies, cultures -- A Reflection of Society wouldn't have evolved without com- For the last fifty years, television has passion and tolerance -- they would been a reflection of American society, but it have fallen apart without it." -- Kes to also has had a substantial impact on public the Doctor (Braga, Menosky, & attitudes. -

DILEMMA DILEMMA Kira Nerys Miles O'brien Worf Bashir Founder

DILEMMA DILEMMA Kira Nerys ❶ ❶ ❶ NOT ENDORSED BY CBS OR PARAMOUNT PICTURES NOT ENDORSED BY CBS OR PARAMOUNT PICTURES NOT ENDORSED BY CBS OR PARAMOUNT PICTURES NOT ENDORSED BY CBS OR PARAMOUNT ALTONIAN BRAIN TEASER INCENTIVE-BASED ECONOMICS OFFICER To solve this holographic puzzle, its challenger must turn the To obtain a rare gift for his father, Jake Sisko and his friend Outspoken Major in Bajoran Militia. Assigned as first multicolor sphere a solid hue using neural theta waves. The Nog bartered, swapped favors, stole a teddy bear, and even officer of Deep Space 9. Former member of Shakaar symbiont Dax tried unsuccessfully for over 140 years. negotiated with Weyoun. resistance cell. Romantically involved with Odo. Leadership Resistance SECURITY Most CUNNING personnel present is “stopped.” If their To get past requires Honor and no SECURITY OR CIVILIAN, Navigation x2 Computer Skill X=3 vs. CUNNING<15, bonus points scored at this spaceline Anthropology, Diplomacy, Youth, and a personnel with location do not count toward winning. Discard dilemma. STRENGTH<8. INTEGRITY 7 CUNNING 7 STRENGTH 8+X 209 VP 210 VP 211 VP Bashir Founder Miles O’Brien Worf ❶ ❶ ❶ NOT ENDORSED BY CBS OR PARAMOUNT PICTURES NOT ENDORSED BY CBS OR PARAMOUNT PICTURES NOT ENDORSED BY CBS OR PARAMOUNT NOT ENDORSED BY CBS OR PARAMOUNT PICTURES NOT ENDORSED BY CBS OR PARAMOUNT MEDICAL ENGINEER OFFICER Changeling posing as Julian Bashir. Tried to destroy Chief of operations on Deep Space 9. Friend of Julian. Klingon strategic operations officer aboard DS9. an entire fleet by causing the Bajoran sun to go nova. Father of Molly and Kirayoshi. -

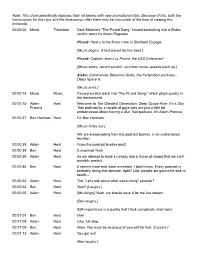

“The Picard Song,” Record-Scratching Into a Sisko- Centric Remix by Adam Ragusea

00:00:00 Music Transition Dark Materia’s “The Picard Song,” record-scratching into a Sisko- centric remix by Adam Ragusea. Picard: Here’s to the finest crew in Starfleet! Engage. [Music begins. A fast-paced techno beat.] Picard: Captain Jean-Luc Picard, the USS Enterprise! [Music slows, record scratch, and then music speeds back up.] Sisko: Commander Benjamin Sisko, the Federation starbase... Deep Space 9. [Music ends.] 00:00:15 Ben Host Welcome to The Greatest Generation: Deep Space Nine. It’s a Star Harrison Trek podcast about Deep Space Nine from a couple of guys who are a little bit embarrassed to have a Star Trek podcast. I’m Ben Harrison 00:00:25 Adam Host I’m Adam Pranica. Pranica 00:00:28 Ben Host Hey! 00:00:29 Adam Host Heeeyyy! Ben, correct me if I’m wrong, but I feel like today’s episode is the first sports episode of Star Trek maybe we’ve ever gotten, right? 00:00:42 Clip Clip [Triumphant, up-tempo music plays, in the style of 1940’s radio.] Jim McKay (ABC’s Wide World of Sports): The human drama of athletic competition. [The music quickly fades out.] 00:00:44 Clip Clip Azetbur (Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country): The very name is racist. 00:00:49 Clip Clip [The triumphant radio music fades in again.] Jim McKay: This is ABC’s Wide World of Sports. 00:00:53 Adam Host And that—I’m not talking about a fake sport like, uh- 00:00:56 Ben Host Right. -

The Klingon Empire 1.1 – the Homeworld 4 1.2 – Important Places 5 1.3 – History of the Empire 6

INSTITUTE OF ALIEN STUDIES Klingon Warrior Academy Warrior’s Manual This document is a publication of STARFLEET Academy - A department of STARFLEET, The International Star Trek Fan Association, Inc. It is intended for the private use of our members. STARFLEET holds no claims to any trademarks, copyrights, or properties held by CBS Paramount Television, any of its subsidiaries, or on any other company's or person's intellectual properties which may or may not be contained within. The contents of this publication are copyright (c)2008 STARFLEET, The International Star Trek Fan Association, Inc. and the original authors. All rights reserved. No portion of this document may be copied or republished in any or form without the written consent of the Commandant, STARFLEET Academy or the original author(s). All materials drawn in from sources outside of STARFLEET are used per Title 17, Chapter 1, Section 107: Limitations on exclusive rights: Fair Use, of the United States code. The material as used is for educational purposes only and no profit is made from the use of the material. STARFLEET and STARFLEET Academy are granted irrevocable rights of usage of this material by the original author. Contributors: Larry French, Carol Thompson, and Wayne L. Killough, Jr., Gary Hollifield, Jr., Eric Schulman,Dewald de Coning, and George Pimentel Published October 2008 Revised March 2011 Updated October 2014 Material herein was copied or summarized from www.ditl.org , http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Klingon and linked pages, http://memory-alpha.org/en/wiki/ , http://startrek.wikia.com/wiki/Klingon , http://en.hiddenfrontier.com/index.php/Klingon , The Klingon Dictionary, Klingon for the Galactic Traveler, Star Trek Encyclopedia: Expanded Version, and various Star Trek episodes and licensed novels. -

2018 Star Trek Deep Space Nine Heroes and Villains

2018 Star Trek DS9 Heroes & Villains Checklist Base Cards # Card Title [ ] 001 Captain Benjamin Sisko [ ] 002 Odo [ ] 003 Lt. Commander Jadzia Dax [ ] 004 Lt. Ezri Dax [ ] 005 Lt. Commander Worf [ ] 006 Jake Sisko [ ] 007 Chief Miles O'Brien [ ] 008 Quark [ ] 009 Doctor Julian Bashir [ ] 010 Colonel Kira Nerys [ ] 011 Gul Dukat [ ] 012 Vedek Bareil Antos [ ] 013 Jennifer Sisko [ ] 014 Damar [ ] 015 Keiko O'Brien [ ] 016 Weyoun) [ ] 017 Brunt) [ ] 018 Vic Fontaine [ ] 019 Enabran Tain [ ] 020 Nog [ ] 021 Kai Winn Adami [ ] 022 Rom [ ] 023 Martok [ ] 024 The Female Changeling [ ] 025 Kasidy Yates [ ] 026 Sarah Sisko [ ] 027 Leeta [ ] 028 Admiral Alynna Nechayev [ ] 029 Gowron [ ] 030 Shakaar Edon [ ] 031 Elim Garak [ ] 032 Luther Sloan [ ] 033 Kai Opaka Sulan [ ] 034 Grand Negus Zek [ ] 035 Mora Pol [ ] 036 Maihar'du [ ] 037 Lursa and B'Etor [ ] 038 Morn [ ] 039 Tosk [ ] 040 The Hunter [ ] 041 Q [ ] 042 Vash [ ] 043 Ty Kajada [ ] 044 Aamin Marritza [ ] 045 Jaro Essa [ ] 046 Li Nalas [ ] 047 General Krim [ ] 048 Verad [ ] 049 Mareel [ ] 050 Melora Pazlar [ ] 051 Pel [ ] 052 Haneek [ ] 053 Martus Mazur [ ] 054 Alexander Rozhenko [ ] 055 Gul Evek [ ] 056 Cal Hudson [ ] 057 Raymond Boone [ ] 058 Michael Eddington [ ] 059 Grilka [ ] 060 Thomas Riker [ ] 061 Korinas [ ] 062 Detective Preston [ ] 063 Michael Webb [ ] 064 Legate Turrel [ ] 065 Gilora Rejal [ ] 066 Vedek Yarka [ ] 067 The Intendant [ ] 068 Adult Jake Sisko [ ] 069 Goran’ Agar [ ] 070 Tora Ziyal [ ] 071 Faith Garland [ ] 072 Admiral Leyton [ ] 073 Kurn [ ] 074 Onaya [ ] 075 Toman’ torax [ ] 076 Trevean [ ] 077 Arne Darvin [ ] 078 Arandis [ ] 079 Fullerton Pascal [ ] 080 Thrax [ ] 081 Captain Sanders [ ] 082 Ikat'ika [ ] 083 Dr. Lewis Zimmerman) [ ] 084 Arissa [ ] 085 Yelgrun [ ] 086 Kimara Cretak [ ] 087 Ishka [ ] 088 Lwaxana Troi [ ] 089 Admiral William Ross [ ] 090 Joseph Sisko [ ] 091 Mullibok [ ] 092 Varani [ ] 093 Colyus [ ] 094 Rurigan [ ] 095 Kor [ ] 096 Koloth [ ] 097 Kang [ ] 098 Kovat [ ] 099 Lt. -

Centric Remix by Adam Ragusea

00:00:00 Music Transition Dark Materia’s “The Picard Song,” record-scratching into a Sisko- centric remix by Adam Ragusea. Picard: Here’s to the finest crew in Starfleet! Engage. [Music begins. A fast-paced techno beat.] Picard: Captain Jean-Luc Picard, the USS Enterprise! [Music slows, record scratch, and then music speeds back up.] Sisko: Commander Benjamin Sisko, the Federation starbase... Deep Space 9. [Music ends.] 00:00:15 Adam Host Welcome to The Greatest Generation: Deep Space Nine. It’s a Star Pranica Trek podcast about Deep Space Nine from the makers of The Greatest Discovery. 00:00:25 Ben Host [Laughs] That’s true, I guess. Harrison 00:00:28 Adam Host I'm Adam Pranica. 00:00:29 Ben Host I’m Ben Harrison. We are primarily known for The Greatest Discovery. 00:00:33 Adam Host [Thoughtfully] Yeah. 00:00:34 Ben Host One thing about the, uh, the MaxFunDrive that I guess will be a kind of distant memory as this is released—but is just ending as we are recording it—is that I get to hear from people about how they found our shows. And, like, I’ve heard from several people like, “Oh, yeah. I found your show The Greatest Discovery when Discovery started, and now I listen to all three of your shows. And I love them!” 00:00:58 Adam Host That’s insane to me. I love it. 00:01:01 Ben Host [Chuckles briefly] I can’t believe that somebody would listen to Greatest Discovery and go, “I want to hear more of this.” 00:01:07 Adam Host I was on the Greatest Gen Reddit not too long ago, where I found a post that was like, “Uh, I came here for the Star Trek shitposting. -

Class, Race, Gender, the Sociology of DS9.)

Aliens in decline and socially-ascending humans. (Class, race, gender, the sociology of DS9.) Camille Akmut Abstract A theory is put forward according to which Star Trek’s DS9 is the meeting place of at least two major populations : socially-declining aliens who seek a reclassification through Federation institutions (Starfleet and adjacent agencies in particular), and humans on a late stage upward trajectory (culminating in e.g. dilettante / artist offspring). 1 Introduction : a historical detour Star Trek’s 24th century has more in common with 20th century sociology than might be obvious at first, with its representation of an ideal Earth society where poverty, inequality and resulting conflicts have “long” been eliminated, weare told1. Past faulty government forms and economies have either been replaced by benev- olent scientific exploration (guaranteed, in theory, by both the laws of theFed- eration Charter and the principle of the Prime Directive) or luxury communist leisure (offered to tourists of Risa, where the old philosophical fantasy of“shared wives” has been realized, and two suns always shine); nonetheless these societies continue to answer to most of the rules and laws established by sociologists. Here, the television series DS9 is reinterpreted as meeting place of not humans and aliens - a naive albeit correct description of this work of science fiction - but as two demographics situated in different stages of their social trajectories. In particular, we argue that the contrasting fates of the duo Jake and Nog offers a strong case for such an interpretation. The tragic fall of the House of Mogh is another. Dr. Bashir is a barely veiled second-generation immigrant success story. -

Major Kira of Star Trek: Ds9: Woman of the Future, Creation of the 90S

MAJOR KIRA OF STAR TREK: DS9: WOMAN OF THE FUTURE, CREATION OF THE 90S Judith Clemens-Smucker A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS December 2020 Committee: Becca Cragin, Advisor Jeffrey Brown Kristen Rudisill © 2020 Judith Clemens-Smucker All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Becca Cragin, Advisor The 1990s were a time of resistance and change for women in the Western world. During this time popular culture offered consumers a few women of strength and power, including Star Trek: Deep Space Nine’s Major Kira Nerys, a character encompassing a complex personality of non-traditional feminine identities. As the first continuing character in the Star Trek franchise to serve as a female second-in-command, Major Kira spoke to women of the 90s through her anger, passion, independence, and willingness to show compassion and love when merited. In this thesis I look at the building blocks of Major Kira to discover how it was possible to create a character in whom viewers could see the future as well as the current and relatable decade of the 90s. By laying out feminisms which surround 90s television and using original interviews with Nana Visitor, who played Major Kira, and Marvin Rush, the Director of Photography on DS9, I examine the creation of Major Kira from her conception to her realization. I finish by using historical and cognitive poetics to analyze both the pilot episode “Emissary” and the season one episode “Duet,” which introduce Major Kira and display character growth. -

The Trekkers Guide to the Sisko Years Ebook

THE TREKKERS GUIDE TO THE SISKO YEARS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK J W Braun | 248 pages | 24 Apr 2019 | Independently Published | 9781095369647 | English | none The Trekkers Guide to the Sisko Years PDF Book Mulder's birthday? Close Window Submit. But I understand Enterprise took it and ran with it. Not mindless fan service but something plot worthy would be amazing. And I think the Mission Log team have done an excellent job discussing the episodes overall no offense to the TrekMovie podcasts, which I also enjoy. Studying ethics, 'Star Trek' style, at Drake. Although the human race right now seems to be having more bad days than good, there have been bright spots. Well, how would you describe Skylines? So impressive to me. As a kid watching Star Trek , I was in love with the awesome space battles and beautiful starships. He did have some heart-to-heart moments about the complicated and unusual relationship between him and his son. By signing up, you agree to receive the selected newsletter s which you may unsubscribe from at any time. At 26 episodes a season, its batting average is excellent. Liz Shannon Miller is a Los Angeles-based writer and editor, and has been talking about television on the Internet since the very beginnings of the Internet. Live long and nitpick. Siddig has some sort of carpet behind him, for example. Facebook Twitter Email. So the relevant question is rather, 'Is there an acceptable version of Ethical It is the main aim of this essay to answer this question. Jake joins his father on the journey, and they are able to spend some quality time together. -

The Mineralogy of Star Trek: the Next Series

The Mineralogy of Star Trek: The Next Series Jeffrey de Fourestier, MSM, FMinSoc Ottawa, Canada [email protected] “I’m a doctor, not a coal miner.” (Dr Leonard McCoy, 1967). _____________________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION In 2005, The Mineralogical Record published as the third issue of the first volume of its on-line e- zine the article “The Mineralogy of Star Trek”1. This was the first systematic effort to give an overview of mineralogy as it exists in the imaginary world of Star Trek in all of its manifestations on film and on television. It was also an effort to put together a comprehensive list of materials referred to in the various Star Trek incarnations that either referred to minerals or mined substances (both real and fictitious) and of materials that might be mistaken for minerals as their names ended with the suffix “ite”. The public reaction to the original article was tremendous, even though it had been written for fun and to make sense of what had been presented in the Star Trek world. One intention of the article was to hopefully influence the producers of Star Trek to improve the mineral nomenclature in future episodes. Unfortunately, the last series “Enterprise” was cancelled at about the same time as the article was published. Perhaps this article and the original article will at least influence future series, films or independent writers and gamesters of the Star Trek genre. The task that was undertaken relied on being able to watch over and over again hundreds of hours of episodes and films available for viewing, collect all possible names, identify them and tabulate them. -

Artifact Equipment Event Dilemma Incident Interrupt

ARTIFACT DILEMMA EQUIPMENT ❶ ❶ ❶ NOT ENDORSED BY CBS OR PARAMOUNT PICTURES NOT ENDORSED BY CBS OR PARAMOUNT NOT ENDORSED BY CBS OR PARAMOUNT PICTURES NOT ENDORSED BY CBS OR PARAMOUNT PICTURES NOT ENDORSED BY CBS OR PARAMOUNT SALTAH’NA CLOCK ARTILLERY ATTACK KUKALAKA Benjamin Sisko constructed a clock while being affected by Jake Sisko and Julian Bashir were pinned down by Klingon Beloved childhood companion (and first surgical patient) of the energy matrix of Saltah’na telepathic spheres. The artillery while attempting to retrieve a portable generator Julian Bashir. Loaned to, and especially treasured by, Leeta. spheres were storing the energy of an ancient power struggle. from their runabout on Ajilon Prime. A timeless symbol of innocence and security. Place on ship or facility here (opponent’s choice). Personnel Kills X personnel (random selection); immediately probe: Your non-Borg personnel present are each INTEGRITY +2, aboard must initiate battle whenever possible (no leader is : X = number of icons on probe card. or +3 if Leeta present. Also, each player is limited to one required and affiliation attack restrictions do not apply). : X = 0 (discard probe card). Otherwise: X = 1. Brain Drain OR one Going to the Top every turn. (Unique.) 135 VP 136 VP 137 VP EVENT INCIDENT INTERRUPT ❶ ❶ ❶ NOT ENDORSED BY CBS OR PARAMOUNT PICTURES NOT ENDORSED BY CBS OR PARAMOUNT PICTURES NOT ENDORSED BY CBS OR PARAMOUNT PICTURES NOT ENDORSED BY CBS OR PARAMOUNT KIVAS FAJO – COLLECTOR THE ART OF DIPLOMACY OUTGUNNED Zibalian trader Kivas Fajo has a spaceborne warehouse of Seeds or plays on table. Your , , Resistance, and Surrounded by a fleet of Suliban ships, Jonathan Archer rare cargo like hytritium as well as a private collection of Orion Syndicate personnel who are using a hand weapon decided to save the lives of his crew by conceding to unique and priceless treasures. -

Greatest Generation: Deep Space Nine

Note: This show periodically replaces their ad breaks with new promotional clips. Because of this, both the transcription for the clips and the timestamps after them may be inaccurate at the time of viewing this transcript. 00:00:00 Music Transition Dark Materia’s “The Picard Song,” record-scratching into a Sisko- centric remix by Adam Ragusea. Picard: Here’s to the finest crew in Starfleet! Engage. [Music begins. A fast-paced techno beat.] Picard: Captain Jean-Luc Picard, the USS Enterprise! [Music slows, record scratch, and then music speeds back up.] Sisko: Commander Benjamin Sisko, the Federation starbase... Deep Space 9. [Music ends.] 00:00:14 Music Music Record scratch back into "The Picard Song," which plays quietly in the background. 00:00:15 Adam Host Welcome to The Greatest Generation: Deep Space Nine. It's a Star Pranica Trek podcast by a couple of guys who are just a little bit embarrassed about having a Star Trek podcast. I'm Adam Pranica. 00:00:27 Ben Harrison Host I'm Ben Harrison. [Music fades out.] We are broadcasting from the podcast bunker, in an undisclosed location. 00:00:35 Adam Host From the podcast bunker past! 00:00:38 Ben Host [Laughing] Yeah. 00:00:39 Adam Host As we attempt to build a runway into a future of shows that we can't possibly predict. 00:00:45 Ben Host It seems more and more uncertain. I don't know. Every podcast is probably doing this episode, right? Like, people are gonna be sick to death— 00:00:52 Adam Host The "Let's talk about what we're doing" episode? 00:00:53 Ben Host Yeah! [Laughs.] 00:00:55 Adam Host [Mockingly] Yeah, we should save it for the live stream.