Glasx Master.Pdf (793.2Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Connotations 14-01

Volume 14, Issue 1 February/March ConNotations 2004 The Bi-Monthly Science Fiction, Fantasy & Convention Newszine of the Central Arizona Speculative Fiction Society April Kicks Off with Ursula K Le Featured Inside Guin, Timothy Zahn, Phoenix SF Tube Talk Special Features ComicCon and World Horror All the latest news about Ursala K LeGuin by Lee Whiteside Scienc Fiction TV shows and other April Events by Lee Whiteside By Lee Whiteside The Arizona Book Festival on Saturday, outreach/scifisymp.html and http:// April 3rd, will feature authors Ursula K. Le www.asu.edu/english/events/outreach/ 24 Frames Jinxed, Hexed, or Cursed: Guin, Alan Dean Foster, and Diana leguin.html All the latest Movie News How I Ruined Harlan Ellison’s Gabaldon on the main stage with CASFS The next day is the Seventh Annual by Lee Whiteside Return to Arizona, Part 2 bringing in Timothy Zahn and other local Arizona Book Festival being held from 10 By Shane Shellenbarger authors for autographing and a special am to 5 pm at the Carnegie Center at 1100 Pro Notes block of programming. LeGuin will also be W. Washingtion in central Phoenix. The Waldorf Conference: appearing at ASU on Friday, April 2nd. Featured authors at the book festival are News about locl genre authors and fans Microphones, scripts, and actors The ASU Department of English Ron Carlson, Nancy Farmer, Alan Dean By Shane Shellenbarger Outreach will be hosting two events on Foster, Diana Gabaldon, Ursula K. Le Musical Notes Friday, April 2nd with Ursula K. LeGuin. Guin, Tom McGuane, and U.S. Supreme In Memorium First will be a daylong Symposium on the Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor. -

STLV17 Program Booklet.Pages

STAR TREK LAS VEGAS 2017 - SCHEDULE of EVENTS MONDAY, JULY 31ST START END EVENT LOCATION VENDORS ROOM – HOURS OF OPERATION: 2:00 PM 7:00 PM VENDORS SET-UP/VENDORS ONLY Amazon TUESDAY, AUGUST 1ST NOTE: Pre-registration is not a necessity, just a convenience! Get your credentials, wristband and schedule so you don't have to wait again during convention days. VENDORS ROOM WILL BE OPEN TOO so you can get first crack at autograph and photo op tickets as well as merchandise! PRE-REGISTRATION IS ONLY FOR FULL CONVENTION ATTENDEES WITH EITHER GOLD, CAPTAIN’S CHAIR, COPPER OR GA WEEKEND. If you miss this pre-registration time, you can come any time that Registration is open! START END EVENT LOCATION VENDORS ROOM – HOURS OF OPERATION: 9:00 AM 3:00 PM VENDORS SET-UP Amazon 6:00 PM 6:45 PM Vendors room open for GOLD ONLY Amazon 6:45 PM 7:30 PM Vendors room open for GOLD and CAPTAIN’S CHAIR ONLY Amazon 7:30 PM 8:15 PM Vendors room open for GOLD, CAPTAIN’S CHAIR and COPPER ONLY Amazon 8:15 PM 11:30 PM Vendors room open for GOLD, CAPTAIN’S CHAIR, COPPER AND GA WEEKEND ONLY Amazon REGISTRATION – HOURS OF OPERATION: 1:30 PM 3:00 PM GOLD PATRONS PRE-REGISTRATION Rotunda 3:00 PM 4:30 PM CAPTAIN’S CHAIR PATRONS PRE-REGISTRATION plus GOLD Rotunda 4:30 PM 7:00 PM COPPER PATRONS PRE-REGISTRATION plus GOLD and CAPTAIN’S CHAIR Rotunda GENERAL ADMISSION FULL WEEKEND PRE-REGISTRATION plus GOLD, CAPTAIN’S 7:00 PM 11:00 PM CHAIR & COPPER Rotunda VENDORS ROOM OPEN (Please see below times for your group’s vendor admission 6:00 PM 11:30 PM hours) Amazon !5 WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 2ND WHERE’S WHAT? CBS All-Access Stage: Brasilia 7 Main Theatre: Pavilion Photo op pick-up: Miranda 1-4 Photo ops: Miranda 5-8 Quark’s: Brasilia 1-3 Secondary Theatre: Brasilia 4-6 Ten Forward Lounge: Tropical G-H The Original Bridge Set: Palma TNG Display: Tropical E-F Vendors: Amazon *END TIMES ARE APPROXIMATE. -

Viewing & Reading Order Abbreviation Key

DC7 Shadows Past and Present, Part 3: SA597 The Shadow of His Thoughts Survival the Hard Way BE107 Wheel of Fire DC8 Shadows Past and Present, Part 4: BE108 Objects in Motion Silent Enemies BE109 Objects at Rest DC9 Laser-Mirror-Starweb, Part 1: SA599 Genius Loci Duet for Human and Narn in C Sharp SC1 Red Fury VIEWING & READING ORDER DC10 Laser-Mirror-Starweb, Part 2: Last update: 2/15/2013 Coda for Human and Narn in B Flat BETWEEN B5 AND CRUSADE 2263 DC11 The Psi Corps and You MP3 * Visions of Peace: A Rangers Novel [ main story ] ABBREVIATION KEY: BE26 A Distant Star BF4 The River of Souls BE B5 episode (filmed) BE27 The Long Dark DN3 The River of Souls [novelization—unavailable ] BF B5 film (TV or direct-to-DVD) BE28 A Spider in the Web BP B5 episode (proposed but not written) BE29 Soul Mates BETWEEN B5 AND CRUSADE 2265 BT B5 film (theatrical—unproduced) BE30 A Race Through Dark Places SO24 The Nautilus Coil B5 DL3 Blood Oath BF6 The Legend of the Rangers: BU episode (unfilmed) BE31 The Coming of Shadows To Live and Die in Starlight CE Crusade episode (filmed) CU Crusade episode (unfilmed) MP2 Ranger Dawning DC B5 comic book (DC, monthly) BE32 Gropos BETWEEN B5 AND CRUSADE 2266 B5 BE33 All Alone in the Night BF5 A Call to Arms DL novel (Dell) BE34 Acts of Sacrifice DN4 A Call to Arms [novelization ] DM B5 comic book (DC, miniseries) DN B5 novelization (Del Rey) BE35 Hunter, Prey DR B5 novel (Del Rey) BE36 There All the Honor Lies CRUSADE 2267 LT B5 mini-comic (with Lost Tales DVD) BE37 And Now For a Word CE1 War Zone MP B5 novel (Mongoose Publishing) 2 BE38 In the Shadow of Z'ha'dum CE2 The Long Road SA B5 short story ( Amazing Stories ) BE39 Knives CE6 Ruling from the Tomb 1 CE8 Appearances and Other Deceits SC B5 short story (Claudia Christian) BE40 Confessions and Lamentations SO B5 short story ( Official Magazine ) DL2 Accusations CE10 The Memory of War B5 BE41 Divided Loyalties CE11 The Needs of Earth WS graphic novel (Wildstorm—unproduced) BE42 The Long, Twilight Struggle CE9 Racing the Night 1 Claudia Christian's short story was released only as a PDF. -

Greatest Generation

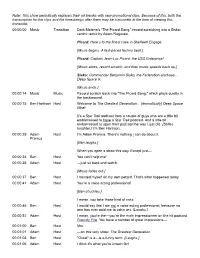

Note: This show periodically replaces their ad breaks with new promotional clips. Because of this, both the transcription for the clips and the timestamps after them may be inaccurate at the time of viewing this transcript. 00:00:00 Music Transition Dark Materia’s “The Picard Song,” record-scratching into a Sisko- centric remix by Adam Ragusea. Picard: Here’s to the finest crew in Starfleet! Engage. [Music begins. A fast-paced techno beat.] Picard: Captain Jean-Luc Picard, the USS Enterprise! [Music slows, record scratch, and then music speeds back up.] Sisko: Commander Benjamin Sisko, the Federation starbase... Deep Space 9. [Music ends.] 00:00:14 Music Music Record scratch back into "The Picard Song," which plays quietly in the background. 00:00:15 Ben Harrison Host Welcome to The Greatest Generation... [dramatically] Deep Space Nine! It's a Star Trek podcast from a couple of guys who are a little bit embarrassed to have a Star Trek podcast. And a little bit embarrassed to open their podcast the way I just did. [Stifles laughter.] I'm Ben Harrison. 00:00:29 Adam Host I'm Adam Pranica. There's nothing I can do about it. Pranica [Ben laughs.] When you open a show this way. Except just— 00:00:34 Ben Host You can't help me! 00:00:35 Adam Host —just sit back and watch. [Music fades out.] 00:00:37 Ben Host I hoisted myself on my own petard. That's what happened today. 00:00:41 Adam Host You're a voice acting professional! [Ben chuckles.] I mean, you take those kind of risks. -

Super! Drama TV August 2020

Super! drama TV August 2020 Note: #=serial number [J]=in Japanese 2020.08.01 2020.08.02 Sat Sun 06:00 06:00 06:00 STAR TREK: DEEP SPACE NINE 06:00 STAR TREK: DEEP SPACE NINE 06:00 Season 5 Season 5 #10 #11 06:30 06:30 「RAPTURE」 「THE DARKNESS AND THE LIGHT」 06:30 07:00 07:00 07:00 CAPTAIN SCARLET AND THE 07:00 STAR TREK: THE NEXT 07:00 MYSTERONS GENERATION Season 6 #19 「DANGEROUS RENDEZVOUS」 #5 「SCHISMS」 07:30 07:30 07:30 JOE 90 07:30 #19 「LONE-HANDED 90」 08:00 08:00 08:00 ULTRAMAN TOWARDS THE 08:00 STAR TREK: THE NEXT 08:00 FUTURE [J] GENERATION Season 6 #2 「the hibernator」 #6 08:30 08:30 08:30 THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO Season 「TRUE Q」 08:30 3 #1 「'CHAOS' Part One」 09:00 09:00 09:00 information [J] 09:00 information [J] 09:00 09:30 09:30 09:30 NCIS: NEW ORLEANS Season 5 09:30 S.W.A.T. Season 3 09:30 #15 #6 「Crab Mentality」 「KINGDOM」 10:00 10:00 10:00 10:30 10:30 10:30 NCIS: NEW ORLEANS Season 5 10:30 DESIGNATED SURVIVOR Season 10:30 #16 2 「Survivor」 #12 11:00 11:00 「The Final Frontier」 11:00 11:30 11:30 11:30 information [J] 11:30 information [J] 11:30 12:00 12:00 12:00 NCIS Season 9 12:00 NCIS Season 9 12:00 #13 #19 「A Desperate Man」 「The Good Son」 12:30 12:30 12:30 13:00 13:00 13:00 NCIS Season 9 13:00 NCIS Season 9 13:00 #14 #20 「Life Before His Eyes」 「The Missionary Position」 13:30 13:30 13:30 14:00 14:00 14:00 NCIS Season 9 14:00 NCIS Season 9 14:00 #15 #21 「Secrets」 「Rekindled」 14:30 14:30 14:30 15:00 15:00 15:00 NCIS Season 9 15:00 NCIS Season 9 15:00 #16 #22 「Psych out」 「Playing with Fire」 15:30 15:30 15:30 16:00 16:00 16:00 NCIS Season 9 16:00 NCIS Season 9 16:00 #17 #23 「Need to Know」 「Up in Smoke」 16:30 16:30 16:30 17:00 17:00 17:00 NCIS Season 9 17:00 NCIS Season 9 17:00 #18 #24 「The Tell」 「Till Death Do Us Part」 17:30 17:30 17:30 18:00 18:00 18:00 MACGYVER Season 2 [J] 18:00 THE MYSTERIES OF LAURA 18:00 #9 Season 1 「CD-ROM + Hoagie Foil」 #19 18:30 18:30 「The Mystery of the Dodgy Draft」 18:30 19:00 19:00 19:00 information [J] 19:00 THE BLACKLIST Season 7 19:00 #14 「TWAMIE ULLULAQ (NO. -

July 15, 2000 SEEING EAR THEATRE JMS' First Audio Drama for The

July 15, 2000 SEEING EAR THEATRE JMS' first audio drama for the Seeing Ear Theatre premiered on Monday night. "The Damned Are Playing at Godzilla's Tonight" - featuring Steve Buscemi launched a 13-week series by JMS of 30 minute dramas at the Sci-Fi Channel’s website. "Rolling Thunder" - featuring Andre Braugher will be available next week.at http://www.scifi.com/set. The dramas are very much like the original radio format and I think you will enjoy the story. You'll need Real Audio loaded to listen. KEEPING UP WITH CAST AND CREW In the latest issue of TV Zone, we get our first glimpse of Marjean Holden in her new role as Atrina on "Beastmaster". We won't be seeing her episodes for a while, but she says "My character is a bit of a bad girl." Quite a change from her role as Dr. Chambers in Crusade. Ranger Bridgitte reports that: Goran Gajic (married to Mira Furlan and director of episodes like "All My Dreams Torn Asunder") recently directed an episode of "OZ", the awarding-winning prison drama produced by Levinson/Fontana. Goran's episode titled, "The Bill Of Wrongs" premieres on Wednesday July 26 on HBO. The episode will be shown several times throughout the week. A schedule of times is posted at: http://mirafurlan.simplenet.com/ozschedule.html GROUP PROJECT As Babylon 5 approaches it's premiere date on the Sci-Fi Channel of September 25, I wonder what resources we could make available to NEW Babylon 5 fans! When the show was on the air, there was a very active on-line community, the Official B5 magazine came out to provide us with information to digest and enjoy, the series would turn up in publications so that we could read about our favorite characters/actors. -

Abstracts and Backgrounds

Abstracts and Backgrounds NAVY Con TABLE OF CONTENTS DESTINATION UNKNOWN ................................................................................. 3 WAR AND SOCIETY ............................................................................................. 5 MATT BUCHER – POTEMKIN PARADISE: THE UNITED FEDERATION IN THE 24TH CENTURY ............ 5 ELSA B. KANIA – BEYOND LOYALTY, DUTY, HONOR: COMPETING PARADIGMS OF PROFESSIONALISM IN THE CIVIL-MILITARY RELATIONS OF BABYLON 5 ............................................ 6 S.H. HARRISON – STAR CULTURE WARS: THE NEGATIVE IMPACT OF POLITICS AND IMPERIALISM ON IMPERIAL NAVAL CAPABILITY IN STAR WARS ................................................................................ 6 MATTHEW ADER – THE ARISTOCRATS STRIKE BACK: RE-ECALUATING THE POLITICAL COMPOSITION OF THE ALLIANCE TO RESTORE THE REPUBLIC ......................................................... 7 LT COL BREE FRAM, USSF – LEADERSHIP IN TRANSITION: LESSONS FROM TRILL .......................... 7 PAST AND FUTURE COMPETITION ................................................................ 8 WILLIAM J. PROM – THE ONCE AND FUTURE KING OF BATTLE: ARTILLERY (AND ITS ABSENCE) IN SCIENCE FICTION .......................................................................................................................... 8 TOM SHUGART – ALL ABOUT EVE: WHAT VIRTUAL FOREVER WARS CAN TEACH US ABOUT THE FUTURE OF COMBAT ................................................................................................................... 10 -

Sayings & Stuff

F e r e n g I R u l e s O f A c q u i s i t i o n ? # RULE SOURCE 1 Once you have their money, you never give it back. (18) DS9: "The Nagus", "Heart of Stone" 2 The best deal is the one that brings the most profit. The 34th Rule (1999) (17) 2.1 Money is everything. (18) Strange New Worlds 9 (2006) (17) 3 Never spend more for an acquisition than you have to. DS9: "The Maquis, Part II" DS9: "The Nagus"; ENT: "Acquisition" 6 Never allow family to stand in the way of opportunity. (1) 7 Keep your ears open. DS9: "In the Hands of the Prophets" 8 Small print leads to large risk. Legends of the Ferengi (17) 9 Opportunity plus instinct equals profit. DS9: "The Storyteller" DS9: "Prophet Motive"; VOY: "False 10 Greed is eternal. Profits" 13 Anything worth doing is worth doing for money. (18) Legends of the Ferengi (17) 16 A deal is a deal. DS9: "Melora" (2) 17 A contract is a contract is a contract, but only between Ferengi. DS9: "Body Parts" 18 A Ferengi without profit is no Ferengi at all. DS9: "Heart of Stone" 19 Satisfaction is not guaranteed. Legends of the Ferengi (17) 21 Never place friendship above profit. DS9: "Rules of Acquisition" DS9: "Rules of Acquisition"; VOY: 22 A wise man can hear profit in the wind. "False Profits" Nothing is more important than your health, except for your money. 23 ENT: "Acquisition" (18) 27 There is nothing more dangerous than an honest businessman. -

Greatestvoters, and That's All Lowercase

Note: This show periodically replaces their ad breaks with new promotional clips. Because of this, both the transcription for the clips and the timestamps after them may be inaccurate at the time of viewing this transcript. 00:00:00 Sound Effect Transition [Computer beeps.] 00:00:01 Promo Clip Enterprise Computer (TNG): Incoming transmission. 00:00:02 Music Music Sweeping orchestral background music. 00:00:03 Ben Harrison Promo Hey, the stakes have never been higher for the election on November 3rd. And we're encouraging Friends of DeSoto to take four steps to make sure your voice is heard. 00:00:11 Adam Promo First, register to vote, or confirm your voter registration, at Vote.org. Pranica 00:00:16 Ben Promo Make a plan to vote safely and securely, and vote early if you can in your area. 00:00:22 Adam Promo Volunteer for a voter outreach campaign, or organization that helps people vote. 00:00:26 Ben Promo And donate to organizations that mobilize voters in every state. 00:00:31 Adam Promo Ben and I have set up a web page where you can find out more, so go to Bit.ly/greatestvoters, and that's all lowercase. Make sure your vote is counted. So together, we can all make sure history never forgets the name Enterprise. [Music stops.] 00:00:45 Sound Effect Transition [Computer beeps.] 00:00:46 Music Transition Dark Materia’s “The Picard Song,” record-scratching into a Sisko- centric remix by Adam Ragusea. Picard: Here’s to the finest crew in Starfleet! Engage. -

The Ship Pdf Free Download

THE SHIP PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Antonia Honeywell | 352 pages | 10 Mar 2016 | Orion Publishing Co | 9781780227344 | English | London, United Kingdom The Ship PDF Book The appeal of free shipping is easy to see. The booming economy in the late s contributed to Malaysia consumers expecting more than a good meal alone, so The Ship introduced live musical entertainment to its selected outlets, bringing in the concept of wine, dine and be entertained. Sisko sternly orders the crew to pull themselves together. The Ship has, by word of mouth , contributed in making Malaysia a popular tourist destination. The solution, he and others said, was to open the Comfort to patients with Covid Dax confirms that the soldiers outside have killed themselves. The Comfort was built to operate in battlefield conditions, and its physicians accustomed to treating young, otherwise healthy soldiers suffering from injuries related to gunshots and bomb blasts. The diminished size and total loss of sight is in me, not in her, and just at the moment when someone at my side says, "She is gone" there are others who are watching her coming, and other voices take up a glad shout: "There she comes! Older internet users preferred free shipping above discounts. Immediately after the runabout's destruction, Jem'Hadar soldiers beam to the surface. Star Trek: Deep Space Nine season 5. Shear contributed reporting. I hope it was worth it. It would be a more honorable death than the one he's enduring. Sisko allows her to collect some of the Changeling's remains before she leaves. Previous episode: " Apocalypse Rising ". -

TRADING CARDS 2016 STAR TREK 50Th ANNIVERSARY

2016 STAR TREK 50 th ANNIVERSARY TRADING CARDS 1995-96 30 Years of Star Trek 1995-96 30 Years of Star Trek Registry Plaques A6b James Doohan (Lt. Arex) 50.00 100.00 A7 Dorothy Fontana 15.00 40.00 COMPLETE SET (9) 100.00 200.00 COMMON CARD (R1-R9) 12.00 30.00 STATED ODDS 1:72 2003 Complete Star Trek Animated Adventures INSERTED INTO PHASE ONE PACKS Captain Kirk in Motion COMPLETE SET (9) 12.50 30.00 1995-96 30 Years of Star Trek Space Mural Foil COMMON CARD (K1-K9) 1.50 4.00 COMPLETE SET (9) 25.00 60.00 STATED ODDS 1:20 COMMON CARD (S1-S9) 4.00 10.00 STATED ODDS 1:12 2003 Complete Star Trek Animated Adventures Die- COMPLETE SET (300) 15.00 40.00 INSERTED INTO PHASE THREE PACKS Cut CD-ROMs PHASE ONE SET (100) 6.00 15.00 COMPLETE SET (5) 10.00 25.00 PHASE TWO SET (100) 6.00 15.00 1995-96 30 Years of Star Trek Undercover PHASE THREE SET (100) 6.00 15.00 COMMON CARD 2.50 6.00 COMPLETE SET (9) 50.00 100.00 STATED ODDS 1:BOX UNOPENED PH.ONE BOX (36 PACKS) 40.00 50.00 COMMON CARD (L1-L9) 6.00 15.00 UNNUMBERED SET UNOPENED PH.ONE PACK (8 CARDS) 1.25 1.50 STATED ODDS 1:18 UNOPENED PH.TWO BOX (36 PACKS) 40.00 50.00 INSERTED INTO PHASE TWO PACKS UNOPENED PH.TWO PACK (8 CARDS) 1.25 1.50 2003 Complete Star Trek Animated Adventures James Doohan Tribute UNOPENED PH.THREE BOX (36 PACKS) 40.00 50.00 1995-96 30 Years of Star Trek Promos UNOPENED PH.THREE PACK (8 CARDS) 1.25 1.50 COMPLETE SET (9) 2.50 6.00 PROMOS ARE UNNUMBERED COMMON CARD (JD1-JD9) .40 1.00 PHASE ONE (1-100) .12 .30 1 NCC-1701, tricorder; 2-card panel STATED ODDS 1:4 PHASE TWO (101-200) -

Valen Feljegyzései #8 8

Valen feljegyzései #8 8. szám 2003. Valen feljegyzései #8 A Csillagközi Szövetség alapító levele „ Az univerzum sok nyelven beszél, de mégis mindig ugyanazon. Valen feljegyzései Ez a nyelv nem a narnok, az emberek, a centaurik, a gaimok vagy a minbarik nyelve. 2003. év (8. szám) Az univerzum a remény, a bizalom, az erő és a szenvedély nyelvén be szél. Ez a szív és a lélek nyelve. De mégis mindig ugyanaz a hang. A Magyar Babylon 5 Klub kiadványa Ez az elődeink hangja, akik rajtunk keresztül szólalnak meg; És az utódaink hangja, akik arra várnak, hogy megszülethessenek. Ez egy halk hang, amely azt mondja: Összetartozunk. A különbö ző vérünk, a bőrszín, a vallás, a szülőbolygó ellenére, mind Egyek vagyunk. A fájdalom, a sötétség, a veszteségek, a félelem e llenére is, Egyek vagyunk. Mi, akik egy közös cél érdekében egyesültünk, ezennel kijelentjük, hogy Az egyetlen igazság és az e gyetlen törvényünk mindig emígy hangzik: A legfontosabb parancsolatunk, hogy szeressük egymást, Legyünk jók egymáshoz. Minden egyes hang gazdagít minket, és minden egyes elveszett hang gyengít minket. Mi vagyunk az univerzum hangja, a teremtés lelkei; A tűz, amely megvilágítja utunkat a jobb jövő felé. Egyek vagyunk.” - G'Kar 60 1 Valen feljegyzései #8 8. szám 2003. Valen feljegyzései #8 2 59 Valen feljegyzései #8 8. szám 2003. Valen feljegyzései #8 igaz történet.” …2245 - öt írunk. A Földi és az akkori Egyes Őrszem, Lenonn, Szövetség a dilgarok felett aratott gy ő- titkos szövetséget köt, hogy minél előbb zelme után határai és befolyása kite r- békét köthessenek a földiekkel. Sikerül Valen jesztésére készül. Egy felderítő egységet egy találko zót megbeszélni, amelyen küldenek a minbari határterületre, részt vesznek: Sheridan, Franklin, hogy információkat szerezzenek a G’Kar és az Egyes Őrszem.