An Analysis of Writings by Elizabeth Tudor, 1544-1565

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'All Wemen in Thar Degree Shuld to Thar Men Subiectit Be': the Controversial Court Career of Elisabeth Parr, Marchioness Of

‘All wemen in thar degree shuld to thar men subiectit be’: The controversial court career of Elisabeth Parr, marchioness of Northampton, c. 1547-1565 Helen Joanne Graham-Matheson, BA, MA. Thesis submitted to UCL for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1 Declaration I, Helen Joanne Graham-Matheson confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 2 Abstract This thesis reconstructs and analyses the life and agency of Elisabeth Parr, marchioness of Northampton (1526-1565), with the aim of increasing understanding of women’s networks of influence and political engagement at the mid-Tudor courts, c. 1547- 1565. Analysis of Elisabeth’s life highlights that in the absence of a Queen consort the noblewomen of the Edwardian court maintained and utilized access to those in power and those with political significance and authority. During the reign of Mary Tudor, Elisabeth worked with her natal family to undermine Mary’s Queenship and support Elizabeth Tudor, particularly by providing her with foreign intelligence. At the Elizabethan court Elisabeth regained her title (lost under Mary I) and occupied a position as one of the Queen’s most trusted confidantes and influential associates. Her agency merited attention from ambassadors and noblemen as well as from the Emperor Maximilian and King Erik of Sweden, due to the significant role she played in several major contemporary events, such as Elizabeth’s early marriage negotiations. This research is interdisciplinary, incorporating early modern social, political and cultural historiographies, gender studies, social anthropology, sociology and the study of early modern literature. -

LEIGHTON: Notes Regarding the 1577 Portrait of Elizabeth Knollys On

19 May 2009 KNOLLYS – LEIGHTON: Notes regarding the 1577 portrait of Elizabeth Knollys on display @ Montacute, her marriage to Thomas Leighton and possible identification of a portrait of ‘an unknown french noblewoman’ as Elizabeth Leighton, nee Knollys Dates need clarification and confirmation where possible. _________________ _____________________________________________________________________ Portrait on left of Elizabeth Knollys, after George Gower: 1577. Source: Montacute1 Portrait on the right described by Philip Mould as Portrait of an unknown french noblewoman: www.historicalportraits.com: Image Library _____________________________________________________________________ The french influence noted by the firm of Philip Mould regarding the latter portrait may be a consequence of the fact that Elizabeth’s husband, Sir Thomas Leighton, served as Governor of Jersey (1570- 1 As an interesting aside, Elizabeth Knolly’s black hat was displayed at the National Maritime Museum in 2003 in an exhibition curated by David Starkey. Elizabeth also presented Elizabeth I with a ‘fayre cap of black vellat’ in 1578/9 1 1609): ‘governor of the ifles of Guernfey and Jcrfey, and con-ftable of the tower of London’. In terms of the wearing of mourning attire, Elizabeth’s brother Edward and her brother-in-law, Gerald Fitzgerald, Baron Offaley, both died in 1580. In 1582/3 her eldest brother, Sir Henry Knollys, and her great-uncle of the same name also died.2 In 1583 her nephew Robert Dudley died. Her mother-in-law, Joyce Leighton nee Sutton, died in 1586. In the context of a large extended Elizabethan family, deaths continued to occur on a frequent basis. These two portraits are quite interesting in juxtaposition. -

War of Roses: a House Divided

Stanford Model United Nations Conference 2014 War of Roses: A House Divided Chairs: Teo Lamiot, Gabrielle Rhoades Assistant Chair: Alyssa Liew Crisis Director: Sofia Filippa Table of Contents Letters from the Chairs………………………………………………………………… 2 Letter from the Crisis Director………………………………………………………… 4 Introduction to the Committee…………………………………………………………. 5 History and Context……………………………………………………………………. 5 Characters……………………………………………………………………………….. 7 Topics on General Conference Agenda…………………………………..……………. 9 Family Tree ………………………………………………………………..……………. 12 Special Committee Rules……………………………………………………………….. 13 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………. 14 Letters from the Chairs Dear Delegates, My name is Gabrielle Rhoades, and it is my distinct pleasure to welcome you to the Stanford Model United Nations Conference (SMUNC) 2014 as members of the The Wars of the Roses: A House Divided Joint Crisis Committee! As your Wars of the Roses chairs, Teo Lamiot and I have been working hard with our crisis director, Sofia Filippa, and SMUNC Secretariat members to make this conference the best yet. If you have attended SMUNC before, I promise that this year will be even more full of surprise and intrigue than your last conference; if you are a newcomer, let me warn you of how intensely fun and challenging this conference will assuredly be. Regardless of how you arrive, you will all leave better delegates and hopefully with a reinvigorated love for Model UN. My own love for Model United Nations began when I co-chaired a committee for SMUNC (The Arab Spring), which was one of my very first experiences as a member of the Society for International Affairs at Stanford (the umbrella organization for the MUN team), and I thoroughly enjoyed it. Later that year, I joined the intercollegiate Model United Nations team. -

Paper 2: Power: Monarchy and Democracy in Britain C1000-2014

Paper 2: Power: Monarchy and democracy in Britain c1000-2014. 1. Describe the Anglo-Saxon system of government. [4] • Witan –The relatives of the King, the important nobles (Earls) and churchmen (Bishops) made up the Kings council which was known as the WITAN. These men led the armies and ruled the shires on behalf of the king. In return, they received wealth, status and land. • At local level the lesser nobles (THEGNS) carried out the roles of bailiffs and estate management. Each shire was divided into HUNDREDS. These districts had their own law courts and army. • The Church handled many administrative roles for the King because many churchmen could read and write. The Church taught the ordinary people about why they should support the king and influence his reputation. They also wrote down the history of the period. 2. Explain why the Church was important in Anglo-Saxon England. [8] • The church was flourishing in Aethelred’s time (c.1000). Kings and noblemen gave the church gifts of land and money. The great MINSTERS were in Rochester, York, London, Canterbury and Winchester. These Churches were built with donations by the King. • Nobles provided money for churches to be built on their land as a great show of status and power. This reminded the local population of who was in charge. It hosted community events as well as religious services, and new laws or taxes would be announced there. Building a church was the first step in building a community in the area. • As churchmen were literate some of the great works of learning, art and culture. -

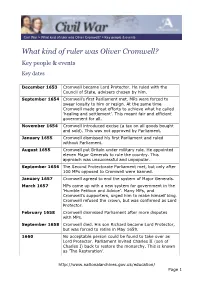

What Kind of Ruler Was Oliver Cromwell? > Key People & Events

Civil War > What kind of ruler was Oliver Cromwell? > Key people & events What kind of ruler was Oliver Cromwell? Key people & events Key dates December 1653 Cromwell became Lord Protector. He ruled with the Council of State, advisers chosen by him. September 1654 Cromwell’s first Parliament met. MPs were forced to swear loyalty to him or resign. At the same time Cromwell made great efforts to achieve what he called ‘healing and settlement’. This meant fair and efficient government for all. November 1654 Cromwell introduced excise (a tax on all goods bought and sold). This was not approved by Parliament. January 1655 Cromwell dismissed his first Parliament and ruled without Parliament. August 1655 Cromwell put Britain under military rule. He appointed eleven Major Generals to rule the country. This approach was unsuccessful and unpopular. September 1656 The Second Protectorate Parliament met, but only after 100 MPs opposed to Cromwell were banned. January 1657 Cromwell agreed to end the system of Major Generals. March 1657 MPs came up with a new system for government in the ‘Humble Petition and Advice’. Many MPs, and Cromwell’s supporters, urged him to make himself king. Cromwell refused the crown, but was confirmed as Lord Protector. February 1658 Cromwell dismissed Parliament after more disputes with MPs. September 1658 Cromwell died. His son Richard became Lord Protector, but was forced to retire in May 1659. 1660 No acceptable person could be found to take over as Lord Protector. Parliament invited Charles II (son of Charles I) back to restore the monarchy. This is known as ‘The Restoration’. -

Why Did Britain Become a Republic? > New Government

Civil War > Why did Britain become a republic? > New government Why did Britain become a republic? Case study 2: New government Even today many people are not aware that Britain was ever a republic. After Charles I was put to death in 1649, a monarch no longer led the country. Instead people dreamed up ideas and made plans for a different form of government. Find out more from these documents about what happened next. Report on the An account of the Poem on the arrest of setting up of the new situation in Levellers, 1649 Commonwealth England, 1649 Portrait & symbols of Cromwell at the The setting up of Cromwell & the Battle of the Instrument Commonwealth Worcester, 1651 of Government http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/ Page 1 Civil War > Why did Britain become a republic? > New government Case study 2: New government - Source 1 A report on the arrest of some Levellers, 29 March 1649 (Catalogue ref: SP 25/62, pp.134-5) What is this source? This is a report from a committee of MPs to Parliament. It explains their actions against the leaders of the Levellers. One of the men they arrested was John Lilburne, a key figure in the Leveller movement. What’s the background to this source? Before the war of the 1640s it was difficult and dangerous to come up with new ideas and try to publish them. However, during the Civil War censorship was not strongly enforced. Many political groups emerged with new ideas at this time. One of the most radical (extreme) groups was the Levellers. -

Cromwelliana 2012

CROMWELLIANA 2012 Series III No 1 Editor: Dr Maxine Forshaw CONTENTS Editor’s Note 2 Cromwell Day 2011: Oliver Cromwell – A Scottish Perspective 3 By Dr Laura A M Stewart Farmer Oliver? The Cultivation of Cromwell’s Image During 18 the Protectorate By Dr Patrick Little Oliver Cromwell and the Underground Opposition to Bishop 32 Wren of Ely By Dr Andrew Barclay From Civilian to Soldier: Recalling Cromwell in Cambridge, 44 1642 By Dr Sue L Sadler ‘Dear Robin’: The Correspondence of Oliver Cromwell and 61 Robert Hammond By Dr Miranda Malins Mrs S C Lomas: Cromwellian Editor 79 By Dr David L Smith Cromwellian Britain XXIV : Frome, Somerset 95 By Jane A Mills Book Reviews 104 By Dr Patrick Little and Prof Ivan Roots Bibliography of Books 110 By Dr Patrick Little Bibliography of Journals 111 By Prof Peter Gaunt ISBN 0-905729-24-2 EDITOR’S NOTE 2011 was the 360th anniversary of the Battle of Worcester and was marked by Laura Stewart’s address to the Association on Cromwell Day with her paper on ‘Oliver Cromwell: a Scottish Perspective’. ‘Risen from Obscurity – Cromwell’s Early Life’ was the subject of the study day in Huntingdon in October 2011 and three papers connected with the day are included here. Reflecting this subject, the cover illustration is the picture ‘Cromwell on his Farm’ by Ford Madox Brown (1821–1893), painted in 1874, and reproduced here courtesy of National Museums Liverpool. The painting can be found in the Lady Lever Art Gallery in Port Sunlight Village, Wirral, Cheshire. In this edition of Cromwelliana, it should be noted that the bibliography of journal articles covers the period spring 2009 to spring 2012, addressing gaps in the past couple of years. -

HERTFORDSHIRE. 11 Flower Arthur Esq

DIRECTORY.] HERTFORDSHIRE. 11 Flower Arthur esq. 36 Princes gate, London SW Loraine Rear-Admiral Sir Lambton ba.rt. Bramford hall, Fordham Edward Snow esq. D.L. Elbrook house, Ash Ipswich, Suffolk; &; 7 Montagu square, London W well, Baldock S.O Loyd Edward Henry esq. D.L. Langleybury, King's Fordham Ernest Oswa1d esq. Odsey ho. Ashwell, Baldock Langley S.O.; & 36 Lowndes square, London SW S.O Loyd Frederic Edward esq. Albyns, Romford, Essex Fordham Francis John esq. D.L. Yew Tree house,Royston Lubbock Henry James esq. 74 Eaton place, London 8 W Fordham Henry John esq. Yew Tree house, Royston Lucas Col. Alfred Geo. C.B., M.V.O. Cliffside, Lowestoft Fordham Herbert George esq. Odsey, Ashwell, Baldock Lucae William esq. 'I'he Firs, Hitchin S.O Luc.as William Tindall esq. Foxholes, Hitchin Foster Professor Geo.Carey, Ladywalk ho.Rickmanswrth Lydekker Capt. Arthur, The Oottage, Harpenden S.O Francis Charles King esq. 7 Granville place, Portman L)'dekker Richard esq. The Lodge, Harpenden S.O square, London W McIlwraith Andrew esq. Campbellfield, St. Michael's, Garrett Edmund William esq. Ardeevin, Downs avenue, St. Albans Epsom, Surrey Macmillan Frederick Orridge esq. D.L. 22 Devonshire pl. Gaussen Casamaijor William esq. Howlands, Hatfield London W Gilbey Sir WaIter, bart. EIsenham hall, Harlow; & MaUl"er Edward esq. Lea side, Hertford Cambridge house, II St. Andrew's place, Regent's Marchand Isidore Henri.Alphonse esq.Orleans,NewBarnet park, London NW Marnham .Alfred esq. Boxm00r, Hemel Hempstead Gilbey Tresham esq. Whitehall, Bishop Stortford Marten George Ernest esq. The Bank, High st.St.Albans Gilliat Capt. -

The Collection of the Cecil Papers, Hatfield House Library, Hertfordshire

Gale Primary Sources Start at the source. The Collection of the Cecil Papers, Hatfield House Library, Hertfordshire Dr Stephen Alford University of Cambridge Various source media, State Papers Online EMPOWER™ RESEARCH The Royal Commission on Historical libraries of the castles and country houses of Queen Manuscripts [1] Victoria’s United Kingdom. In 1872 the Reverend J. S. Brewer, classical scholar The Cecil Papers in 1872 and editor of the great series of Letters and Papers of Brewer found at Hatfield 310 ‘stout volumes’ and 3,000- the reign of King Henry VIII, completed his first report on 4,000 other papers unbound, enough, he thought, to fill the papers in the collection of the Marquess of 20 volumes more. Even those documents arranged in Salisbury at Hatfield House in Hertfordshire. Even an volumes were not in chronological order, and this editor as experienced and distinguished as Brewer was became Brewer’s great headache in his first staggered by the scale of what he found at Hatfield: assessment of the collection: he was compelled, as he ‘The collection is so large and the papers so important put it, ‘to recollate all that had been previously done, that I was at a great loss how to begin and where to and arrange the whole series in one uniform end.’ chronological order; not indeed altering the place or John Brewer visited the Library of Hatfield House on position of the papers in the volumes where they now behalf of a Royal Commission on Historical stand, but leaving them as before’.[2] Manuscripts (popularly known as the Historical Brewer had expected to find the Cecil Manuscripts in Manuscripts Commission, or HMC) set up in 1869. -

Famouskin.Com Relationship Chart of Warren Buffett Chairman & CEO, Berkshire Hathaway 13Th Cousin 5 Times Removed of William C

FamousKin.com Relationship Chart of Warren Buffett Chairman & CEO, Berkshire Hathaway 13th cousin 5 times removed of William C. C. Claiborne 1st Governor of Louisiana Sir Thomas Mowbray Elizabeth of Arundel Isabel Mowbray Margaret Mowbray Sir James Berkeley Sir Robert Howard Maurice Berkeley Sir John Howard Isabel Mead Katherine Moleyns Anne Berkeley Sir Thomas Howard Sir William Dennis Elizabeth Tilney Isabel Dennis Elizabeth Howard Sir John Berkeley Thomas Boleyn Sir Richard Berkeley Mary Boleyn Elizabeth Jermy Sir William Carey Mary Berkeley Catherine Carey Sir John Hungerford Sir Francis Knollys Bridget Hungerford Anne Knollys FamousKin.comSir William Lisle Sir Thomas West A B © 2010-2021 FamousKin.com Page 1 of 3 10 Oct 2021 FamousKin.com Relationship Chart of Warren Buffett to William C. C. Claiborne A B John Lisle Gov. John West Alice Beckenshaw Anne - - - - - - Bridget Lisle Col. John West Leonard Hoar Unity Croshaw Bridget Hoar Ann West Rev. Thomas Cotton Henry Fox Leonard Hoar Cotton Ann Fox Hannah - - - - - - Thomas Claiborne Thomas Cotton Nathaniel Claiborne Agnes Smith Jane Cole Mary Cotton William Claiborne Stephen Pennell Mary Leigh Thomas Jefferson Pennell William C. C. Claiborne Rhoda A. Mallett 1st Governor of Louisiana Deborah Collamore Pennell John Watson Susan Ann Watson Ford Bela Barber Stella Frances Barber FamousKin.comJohn Ammon Stahl C © 2010-2021 FamousKin.com Page 2 of 3 10 Oct 2021 FamousKin.com Relationship Chart of Warren Buffett to William C. C. Claiborne C Leila Stahl Howard Homan Buffett Warren Buffett Chairman & CEO, Berkshire Hathaway FamousKin.com © 2010-2021 FamousKin.com Page 3 of 3 10 Oct 2021 . -

Part 1), September 2019 Historic Environment Associates

Appendix 22: A conservation management plan for the central area of the Ashridge Estate (part 1), September 2019 Historic Environment Associates Ashridge Estate A Conservation Management Plan for the Central Area of the Ashridge Estate Part 1 Report Final September 2019 Contents Contents 1 Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 1 Background to the study ............................................................................................................ 2 National Trust Policy .................................................................................................................. 2 Spirit of the Place ....................................................................................................................... 4 Methodology .............................................................................................................................. 4 Authorship ................................................................................................................................. 5 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................... 5 2 Baseline Information ......................................................................................................... 9 Ownership and Land Management ............................................................................................ 9 Covenants and Legal Restrictions on Management -

August 2013 2 September 2013 4 October 2013

In this issue... Welcome to the August edition of Your Berkhamsted By now the school holidays will be well underway and hopefully the sun will still be blazing down. There’s plenty going on in and around town this month and we have more ideas of where to take the kids on a day out, as well as recipes to try and a bit of history thrown in for good measure. Enjoy the rest of your summer! Helen Dowley, Editor Berkhamsted in the News 3 Local Noticeboard 7 Days Out With the Kids 8-9 My Berkhamsted 11 Local Professor’s Life Story 12 Heritage Open Days 13 Bike ’n Hike 14 Berkhamsted’s Swifts 15 Parish Pages 17 Hospice News 20-21 Chilterns Countryside Festival 23 Census Corner 25 B-Hive 27 A Century In and Out of Berkhamsted 28 Recipe 29 Summer Sport 30 Kids’ Recipe 31 Front cover: Clouds by Terry Wood Photo credits: P.16 Common Swift in Flight by Pawel Kuzniar The Town and Parish Magazine of St Peter's Great Berkhamsted Responsibility for opinions expressed in articles and letters published in this magazine and for the accuracy of any statements in them rests solely with the individual contributor. 2 Berkhamsted in the News In this month’s skip across the broadband airways, Julian Dawson discovers that surrealism is alive and well. For absolutely no reason at all let’s start Mix96.co.uk reports on an extraordinary this month’s column with a piece of attempt to construct a Travelodge kitsch from felting.craftgossip.com.