Luminous Color in Architecture: Exploring Methodologies for Design- Relevant Research Ute C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Minstrel; Or the Progress of Genius

The Minstrel; or the Progress of Genius By James Beattie THE MINSTREL; IN TWO BOOKS. _Me vero primum dulces ante omnia Musæ, Quarum sacra fero, ingenti perculsus amore, Accipiant.----_ VIRGIL. THE MINSTREL; OR, THE PROGRESS OF GENIUS. BOOK FIRST. I. Ah! who can tell how hard it is to climb The steep, where Fame's proud temple shines afar! Ah! who can tell how many a soul sublime Has felt the influence of malignant star, And waged with Fortune an eternal war! Checked by the scoff of Pride, by Envy's frown, And Poverty's unconquerable bar, In life's low vale remote has pined alone, Then dropt into the grave, unpitied and unknown! II. And yet, the languor of inglorious days Not equally oppressive is to all. Him, who ne'er listened to the voice of praise, The silence of neglect can ne'er appal. There are, who, deaf to mad Ambition's call, Would shrink to hear th' obstreperous trump of Fame; Supremely blest, if to their portion fall Health, competence, and peace. Nor higher aim Had He, whose simple tale these artless lines proclaim. III. This sapient age disclaims all classic lore; Else I should here, in cunning phrase, display, How forth THE MINSTREL fared in days of yore, Right glad of heart, though homely in array; His waving locks and beard all hoary grey: And, from his bending shoulder, decent hung His harp, the sole companion of his way, Which to the whistling wind responsive rung: And ever as he went some merry lay he sung. -

Josh Groban Releases Noël (Deluxe Edition) in Celebration of Its 10Th Anniversary

JOSH GROBAN RELEASES NOËL (DELUXE EDITION) IN CELEBRATION OF ITS 10TH ANNIVERSARY ALBUM AVAILABLE HERE GROBAN'S FIRST COFFEE TABLE BOOK STAGE TO STAGE: MY JOURNEY TO BROADWAY OUT NOVEMBER 21ST Los Angeles, CA (November 3, 2017) - Multi-platinum, international recording artist and songwriter Josh Groban released a deluxe version of his beloved Christmas album Noël on CD and all digital formats today via Reprise Records. The album can be ordered HERE. Originally released on October 9, 2007, this Grammy nominated holiday recording remains one of the best-selling Christmas albums of all time, selling over 7.5 million copies worldwide. The new album consists of the original 13 tracks with an extra six new songs, including four brand new, never before released recordings: • White Christmas - a gorgeous, brand new recording with a full 70 piece orchestra recorded in Abbey Road, London. • Christmas Time Is Here - duet with the legendary Tony Bennett. This incredibly famous, cross generational song from "A Charlie Brown Christmas" will surely be a hit at family Christmas parties. • Have Yourself A Merry Little Christmas- following Josh's platinum album Stages, he wanted a holiday song that matched the theme of Stages and found that in this famous Christmas song from the show/film Meet Me In St. Louis. • Happy XMas (War is Over) - the poignant, classic Christmas song written by John Lennon & Yoko Ono with a powerful message that seems more relevant now than ever (fans who pre-order the new album will receive this song as an instant grat track TODAY). • Believe - the Academy Award-nominated song from the Polar Express film soundtrack, never before available on a Josh Groban release. -

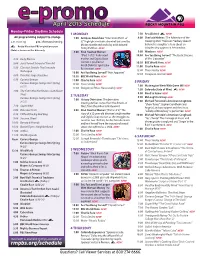

Full Schedule.Indd

April 2013 Schedule ROCKY MOUNTAIN PBS Monday-Friday Daytime Schedule 1 MONDAY 7:30 Arts District a NEW! All programming subject to change 7:00 Antiques Roadshow “Cincinnati (Part 1 of 8:00 Sherlock Holmes “The Adventure of the a.m. morning p.m. afternoon/evening 3)” Highlights include a baseball bat used by Creeping Man” Professor Presbury doesn’t Mickey Mantle and works by artist Edward believe his daughter’s story about an a = Rocky Mountain PBS original program Henry Potthast. NEW! intruder who appears at her window. (Date) = shown on this date only 8:00 Kind Hearted Woman 9:00 Windsors NEW! “(Part 1 of 2)” A divorced 10:00 Are You Being Served? “The Erotic Dreams 4:30 Body Electric mother and Oglala Sioux of Mrs. Slocombe” woman is profiled on 5:00 Jerry Yarnell School of Fine Art 10:30 BBC World News NEW! North Dakota’s Spirit Lake 11:00 Charlie Rose NEW! 5:30 Classical Stretch: The Esmonde Reservation. NEW! Technique 12:00 Tavis Smiley NEW! 10:00 Are You Being Served? “Heir Apparent” 12:30 European Journal NEW! 6:00 Priscilla’s Yoga Stretches 10:30 BBC World News NEW! 6:30 Curious George 11:00 Charlie Rose NEW! 5 FRIDAY Curious George Swings Into Spring 12:00 Tavis Smiley NEW! 7:00 Washington Week With Gwen Ifill NEW! (4/22) 12:30 Religion & Ethics Newsweekly NEW! 7:30 Colorado State of Mind a NEW! 7:00 The Cat in the Hat Knows a Lot About 8:00 Need to Know NEW! That! 2 TUESDAY Curious George Swings Into Spring 8:30 McLaughlin Group NEW! 7:00 History Detectives The detectives (4/22) 9:00 Michael Feinstein’s American Songbook investigate four stories from the American “Show Tunes” Stephen Sondheim and 7:30 Super Why! West, from the rodeo to Hollywood. -

Josh Groban Encore Fathom Event

“Josh Groban: All That Echoes Artist Cut” Brings Special Edition of Magical Performance To U.S. Cinemas This July NCM Fathom Events and Warner Bros. Records Present Spectacular Lincoln Center Concert Event Originally Broadcast on the Eve of Groban’s Latest No. 1 Album Release Centennial, Colo. – June 24, 2013 – With overwhelming fan demand continuing for Josh Groban’s No. 1 album released earlier this year, one of the most powerful voices in modern popular music is returning to the big screen in a special edition of “Josh Groban: All That Echoes Artist Cut.” This special event, a personal collaboration between Josh Groban, Warner Bros. Records and NCM Fathom Events, will hit select movie theaters nationwide on Tuesday, July 16 at 7:30 p.m. local time, with an updated welcome message to movie theater audiences from the singer. Groban was up-close and candid with fans during the original February 4 premiere event, broadcast from New York’s famed Lincoln Center, where he performed hits and selections from his just- released album “All That Echoes,” which debuted at No. 1 on the Billboard 200. In addition to his original February Q&A session with fans who texted and tweeted from around the country, updates to this special encore will include a very special behind- the-scenes journey through the creative process of the making of “All that Echoes” as seen through the eyes of Groban himself. Tickets for “Josh Groban: All That Echoes Artist Cut” are available at participating theater box offices and online at www.FathomEvents.com. For a complete list of theater locations and prices, visit the NCM Fathom Events website (theaters and participants are subject to change). -

Has Half a Century of World Music Trade Displaced Local Culture?

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Real Estate Papers Wharton Faculty Research 6-2013 Pop Internationalism: Has Half a Century of World Music Trade Displaced Local Culture? Fernando V. Ferreira University of Pennsylvania Joel Waldfogel University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/real-estate_papers Part of the International and Intercultural Communication Commons, Music Commons, Other Communication Commons, and the Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons Recommended Citation Ferreira, F. V., & Waldfogel, J. (2013). Pop Internationalism: Has Half a Century of World Music Trade Displaced Local Culture?. The Economic Journal, 123 (569), 634-664. http://dx.doi.org/DOI: 10.1111/ ecoj.12003 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/real-estate_papers/37 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Pop Internationalism: Has Half a Century of World Music Trade Displaced Local Culture? Abstract Advances in communication technologies have increased the availability of cultural goods across borders, raising concerns that cultural products from large economies will displace those in smaller economies. This article provides stylised facts about global music consumption and trade since 1960 using a unique data on popular music charts corresponding to over 98% of the global music market. Contrary to growing fears about large-country dominance, our gravity estimates show a substantial bias towards domestic music that has, perhaps surprisingly, -

The Mysteries of Udolpho: a Gothic Romance (Reader's Edition)

• • Ann Radcliffe the Mysteries of Udolpho A Gothic Romance READER’S EDITION Edited by Sandra K. Williams Idle Spider Books Sacramento, California • • the mysteries of udolpho : a gothic romance (Reader’s Edition) by Ann Radcliffe Edited by Sandra K. Williams Notes, map, and editorial changes copyright © 2010 Sandra K. Williams All rights reserved The Mysteries of Udolpho was fi rst published in 1794 This edition published in 2010 by Idle Spider Books www.idlespiderbooks.com Design and typesetting by Williams Writing, Editing & Design Text set in ITC Garamond Book Condensed; display set in Garamond No. 2 and Bible Script Idle Spider Books™ and the spider colophon are trademarks of Williams Writing, Editing, & Design www.williamswriting.com isbn 978-0-9797290-0-3 Printed on acid-free paper ♾ in the United States of America editor’s note This edition has been copyedited to current American prac- tice in respect to punctuation. Spelling has been standardized throughout using the author’s preferred spelling when it could be determined. In some places words and phrases have been reordered—and in a few cases altered or removed—to fl ow more smoothly to modern ears and to improve ease of comprehen- sion. Long passages of verse that aren’t related to the story have been excised, the chapters have been renumbered, and the parts named and redistributed. However, no scenes, no events, and no descriptions have been removed: the work stands as Ann Radcliffe wrote it, polished for today’s readers. If you need an exact reproduction of the original text or exten- sive footnotes, you may prefer one of the many other editions that are available. -

View the Standards

Capital Projects & Construction TECHNICAL DESIGN STANDARDS P Revision 4C, January 31, 2021 INTRODUCTION Revision 4C, January 31, 2021 Dear User, Portland State University strives to create a quality environment for all students and users of its facilities. The Capital Projects and Construction Department (CPC), as part of PSU’s Office of Planning, Construction & Real Estate, manages all renovation and construction projects on the PSU Campus. We approach this responsibility with enthusiasm, which is reflected in our department’s mission: “To design and build a modern, sustainable campus that enhances our student learning experience and reinforces the academic mission”. With the goal of clearly and concisely communicating our standards, including preferences and recommendations, to the team of Consultants and Contractors who work on our projects, we composed these Technical Design Standards. The work involved in the creation of this document comprised obtaining information from important stakeholders on campus, including the professionals who manage PSU’s daily campus and maintenance activities, as well as the leaders who define PSU’s strategic approach and future vision. Their expertise, experience, ideas, and recommendations, in addition to our own knowledge of the best design and construction practices, are incorporated into this document to guide and assist Campus design efforts. The PSU CPC Technical Design Standards are divided into sections that follow the Construction Specifications Institute (CSI) standards. This format facilitates the use and familiarity by the design and construction professionals. In addition, the guidelines in this document focus on PSU’s vision to create facilities which have the following characteristics: o Adaptability Over the course of their lifetime, PSU buildings, may be re-purposed for uses that were likely not considered at the time of their design. -

Shakespeare Play Is Mix of Laughter, Love, Chaos

Volume 85 - Issue 15 February 15, 2013 Shakespeare Heemstra Radio play is mix of laughter, turns down tunes love, chaos On October 26, 2012, Dr. BY KALI WOLKOW John Brogan sent an email to h* OPINION EDITOR Radio with a list of guidelines Love triangles are complicated, regarding the continuation of messy situations. In the “Comedy the music, one of which included of Errors,” this “messy situation” a volume decrease. According becomes more like a chaotic love to the guidelines, “The volume hexagon. A jealous wife mistakes her must be turned down during brother-in-law for her husband. Her class periods. The volume can be brother-in-law, in turn, falls for her increased during the 10-minute sister. Meanwhile, her actual husband breaks between classes but not is locked out of his own house, and the beyond an acceptable level. lives of their servants spiral into a tizzy: Once the next class period begins, Nell, a kitchen wench, is engaged to one the music must once again be of the twin Dromio servants but soon turned down to a quieter level.” mistakenly sets her sights on the other. The termination of the station Sound confusing? It might be. It’s after chapel caused frustration also funny. and disappointment within Shakesphere’s play, “Comedy Heemstra and across campus. of Errors,” will be performed by “It’s something like taking Northwestern students and directed by away Melon and Gourd week Jeff Barker starting today at 7:30 p.m. in because it’s traumatizing to the Allen Black Box Theatre. -

Guns N' Roses Entity Partnership Citizenship California Composed Of: W

Trademark Trial and Appeal Board Electronic Filing System. http://estta.uspto.gov ESTTA Tracking number: ESTTA966168 Filing date: 04/10/2019 IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD Notice of Opposition Notice is hereby given that the following party opposes registration of the indicated application. Opposer Information Name Guns N' Roses Entity Partnership Citizenship California Composed Of: W. Axl Rose Saul Hudson Michael "Duff" McKagan Address c/o LL Management Group West, LLC 5950 Canoga Ave., Ste. 510 Woodland Hills, CA 91367 UNITED STATES Attorney informa- Jill M. Pietrini Esq. tion Sheppard Mullin Richter & Hampton LLP 1901 Avenue of the Stars, Suite 1600 Los Angeles, CA 90067 UNITED STATES [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], MDan- [email protected], [email protected], RLHud- [email protected] 310-228-3700 Applicant Information Application No 87947921 Publication date 03/12/2019 Opposition Filing 04/10/2019 Opposition Peri- 04/11/2019 Date od Ends Applicant ALDI Inc. 1200 N. Kirk Road Batavia, IL 60510 UNITED STATES Goods/Services Affected by Opposition Class 029. First Use: 0 First Use In Commerce: 0 All goods and services in the class are opposed, namely: cheese, namely, cheddar cheese Grounds for Opposition Priority and likelihood of confusion Trademark Act Section 2(d) False suggestion of a connection with persons, Trademark Act Section 2(a) living or dead, institutions, beliefs, or national symbols, or brings them into contempt, or disrep- ute Mark Cited by Opposer as Basis for Opposition U.S. Application/ Registra- NONE Application Date NONE tion No. -

JOSH GROBAN LIVE: All That Echoes" Intimate Performance Broadcast to U.S

January 10, 2013 "JOSH GROBAN LIVE: All That Echoes" Intimate Performance Broadcast to U.S. Cinemas This February NCM® Fathom Events and Warner Bros. Records Present Special One-Night Event with Interactive Fan Q&A Session Broadcast Live from the Famed Allen Room in New York on Monday, Feb. 4 CENTENNIAL, Colo.--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- Showcasing one of the most powerful and unique voices in modern popular music, NCM® Fathom Events and Warner Bros. Records will present "JOSH GROBAN LIVE: All That Echoes." Broadcasting the superstar singer's new album release event to select movie theaters nationwide on Monday, Feb. 4 at 7:00 p.m. ET/6:00 p.m. CT and tape delayed at 7:30 p.m. MT/PT, this intimate one-night event will feature Groban as he performs hits from his 12-year career, highlighted by exclusive selections from his new album, "All That Echoes." Fans will be among the first to hear these new songs performed live, on the eve of the album's release as well as request songs to be included in Groban's playlist performed from New York's famed Allen Room which features a stunning 50' x 90' window overlooking Central Park. Groban will also answer fan questions submitted via Twitter and text messages prior to this live event. Tickets for "JOSH GROBAN LIVE: All That Echoes" are available at participating theater box offices and online at www.FathomEvents.com. For a complete list of theater locations and prices, visit the NCM Fathom Events website (theaters and participants are subject to change). -

Exclusive the Beastie Boy Behind the Bad Brains Comeback >P.5

AVRIL Rnirw Our EXPERIENCE THE BU EXCLUSIVE THE BEASTIE BOY BEHIND THE BAD BRAINS COMEBACK >P.5 4 li BRITNEYe BRANDING JAKES A 13EATING FINLAND: COLD COUNTRY, 91AR 10, 2007 HOT MARKET www.billboar > P.27 www.billboaru., ' r YOU US $6.99 CAN $8.99 UK £5.50 _at WOULD ****SCH 3-DIGIT 907 IA $6 991JS $8 99CAN 1113XACTCC ........... ..... C31.24080431 MAR08 REG A04 00/005 1 0> RD MONTY GREENLY 0074 RE 374D ELM AVE 1 A LONG BEACH CA 90807-3402 001261 > 11 P.15 o 71896 47205 9 J.T www.americanradiohistory.com soothing décor flawless design sublime amenities what can we do for you? AL_>(THE overnight or over time 203 impeccable guest rooms and deluxe suites interior design by David Rockwell flat- screen TVs in all bedrooms, bathrooms & living rooms 24 -hour room service from Riingo`' and award -winning chef, Marcus Samuelsson The Alex Hotel 205 East 45th Street at Third Avenue New York, NY 10017 212.867.5100 www.thealexhotel.com ©2007 The Alex Hotel The2eadimfiHotelsoftheWorld g www.americanradiohistory.com Billboard CON11 = \'l'S PAGE ARTIST/ TITLE NORAH JONES / THE BILBOARD 200 48 NOT TOO LATE NICKEL CREEK / TOP 3LUEGRASS 58 REASONS WHY (THE VERY BEST) KENNY WAYNE SHEPHERD I TOP BLUES 55 10 DAYS OUT BLUES FROM THE BfCKEJADi TOBYMAC / TOP CHRISTIAN 63 (PORTABLE SOUNDS) DIXIE CHICKS / TCP COUNTRY 58 TAKING THE LONG WAY GNARLS BARKLEY / TOP ELECTRONIC 61 ST ELSEWHERE J VARIOUS ARTISTS / -OP GOSPEL 63 WOW GOSPEL 2007 SILVERSUN PICKUPS / TOP HEATSEEKERS 65 CARNAVAS J THE SHINS / TOP INDEPENDENT 64 WINCING THE NIGHT AWAY VALENTIN ELIZALDE / TOP LATIN ' 60 VENCEDOR GERALD LEVERT / TOP R &B-HIP -HOP 55 IN MY SONGS UPFRONT WCINDA WILLIAMS / TASTE MAKERS 64 WEST 5 INSANE IN THE 16 Global CELTIC WOMAN / BRAINS Hardcore 18 The Indies TOP WORLD 64 A NEW JOURNEY legends get a lift 19 Legal Matters OSINGI_ES PAGE ARTIST / TITLE from a Beastie 20 On The Road JOHN MAYER / on new album. -

![The Poetical Works of Beattie, Blair, and Falconer by Rev. George Gilfillan [Ed.]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5551/the-poetical-works-of-beattie-blair-and-falconer-by-rev-george-gilfillan-ed-6945551.webp)

The Poetical Works of Beattie, Blair, and Falconer by Rev. George Gilfillan [Ed.]

The Poetical Works of Beattie, Blair, and Falconer by Rev. George Gilfillan [Ed.] The Poetical Works of Beattie, Blair, and Falconer by Rev. George Gilfillan [Ed.] Produced by Jonathan Ingram, Clytie Siddall, Charles Franks and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team. THE POETICAL WORKS OF BEATTIE, BLAIR, AND FALCONER. With Lives, Critical Dissertations, and Explanatory Notes, BY THE REV. GEORGE GILFILLAN. page 1 / 436 CONTENTS Beattie's Poetical Works The Life and Poetry of James Beattie The Minstrel; or, the Progress of Genius Miscellaneous Poems Ode to Hope Ode to Peace Ode on Lord Hay's Birthday The Judgment of Paris The Triumph of Melancholy Elegy Elegy, written in the year 1758 Retirement The Hermit On the Report of a Monument to be erected in Westminster Abbey, to the Memory of a late Author (Churchill) The Battle of the Pigmies and Cranes The Hares. A Fable The Wolf and Shepherds. A Fable Song, in imitation of Shakspeare's "Blow, blow, thou winter wind" To Lady Charlotte Gordon, dressed in a Tartan Scotch Bonnet, with Plumes, &c Epitaph: being part of an Inscription designed for a Monument erected by a Gentleman to the Memory of his Lady Epitaph on Two Young Men of the name of Leitch, who were drowned in page 2 / 436 crossing the River Southesk Epitaph, intended for Himself Blair's Poetical Works The Life of Robert Blair The Grave A Poem, dedicated to the Memory of the late learned and eminent Mr William Law, Professor of Philosophy in the University of Edinburgh Falconer's Poetical Works The Life of William Falconer The Shipwreck Occasional Elegy, in which the preceding narrative is concluded Miscellaneous Poems The Demagogue A Poem, sacred to the Memory of His Royal Highness Frederick Prince of Wales Ode on the Duke of York's second departure from England as Rear-Admiral The Fond Lover.