Historic Resources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The York River: a Brief Review of Its Physical, Chemical and Biological Characteristics

W&M ScholarWorks Reports 1986 The York River: A Brief Review of Its Physical, Chemical and Biological Characteristics Michael E. Bender Virginia Institute of Marine Science Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/reports Part of the Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons, Marine Biology Commons, Natural Resources and Conservation Commons, and the Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons Recommended Citation Bender, M. E. (1986) The York River: A Brief Review of Its Physical, Chemical and Biological Characteristics. Virginia Institute of Marine Science, William & Mary. https://doi.org/10.21220/V5JD9W This Report is brought to you for free and open access by W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Reports by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The York River: A Brief Review of Its Physical, Chemical and Biological Characteristics ·.by · Michael E. Bender .·· Virginia Institute of Marine Science School ofMar.ine Science The College of William and Mary Gloucester, Point; Virginia 23062 The York River: A Brief Review of Its Physical, Chemical and Biological Characteristics by · Michael E. Bender Virginia Institute of Marine Science School of Marine Science The College of William and Mary Gloucester Point, Virginia 23062 LIST OF FIGURES Figure Page 1. The York River . 5 2. The York River Basin (to the fall line) .. 6 3. Mean Daily Water Temperatures off VIMS Pier for 1954- 1977 [from Hsieh, 1979]. • . 8 4. Typical Water Temperature Profiles in the Lower York River approximately 10 km from the River Mouth . 10 5. Typical Seasonal Salinity Profiles Along the York River. -

Nomination Form

UPS Form 10-WO LRI 16. tucr-uul (Oct. 1990) United States Doparbent of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM I. Name of Property ---. - ----I- ---. historic name Dam Number One Battlefield Site other namesfsite number -Lee's Mill Battlefield; Newport News Park; VDIiR File No. 121-60 ------ ---- -- -- ----.--. 2. Location --- -------- - ----.--. street & number- 13560 Jefferson Avenue not for publication x city or town -Newport News vicinity N/f state Virginia code OA county Newport News (independent code 700 zip code 2360. citvl -- -- - .- - - - 3. State/Federal Agency Certification - - - - - - - - - As the designated authority uder the National Historic Preservatim Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this -x- nminati request for determination of eligibility wets the doc-tatim standards for registering prowrties in the NatimaI Register -Historic Places and meets the procedural ard professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my Opinion, the Property -x - mets does mt imt the National Register Criteria. I recumem that this property be considerea significant - nationai -x - staten=- locally. ( - See cmtimation sheet for additimal camnents.) '.L- ,!-;'&,; <. ,- -/ - L : -. , . ,, flk'~- c. ' -. Sfgnature -of certifying official/Title Date , > L..fl. -, ,J , -..., ,.-.-<: ,LA- ,,,,: L ',' /.. / 2:1 L ,i.&~&.~/,/,s 0*A: i 2.74 ," - .- .-- L, ,, Virginia Department of Historic Resources State or Federal agency and bureau In my opinion, the pro~erty- meets - does not meet tne Nationai Register critsia. ( See cmtiowrim sheet for addiricnai cmrs.) signature of carmenring or omer official Dare State or FederaL agency am bureau -------- --------------- --------------- ------- ------------- --4. National Park Service-------------------- Certification ------------- ----------- I, hereby certify that this property is: entered in the Naticnal Register - See cmtirrJarion sheet. -

From August, 1861, to November, 1862, with The

P. R. L. P^IKCE, L I E E A E T. -42 4 5i f ' ' - : Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from The Institute of Museum and Library Services through an Indiana State Library LSTA Grant http://www.archive.org/details/followingflagfro6015coff " The Maine boys did not fire, but had a merry chuckle among themselves. Page 97. FOLLOWING THE FLAG. From August, 1861, to November, 1862, WITH THE ARMY OF THE POTOMAC. By "CARLETON," AUTHOR OF "MY DAYS AND NIGHTS ON THE BATTLE-FIELD.' BOSTON: TICKNOR AND FIELDS. 1865. Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1864, by CHARLES CARLETON COFFIN, in the Clerk's Office of the District Court for the District of Massachusetts. University Press: Welch, Bigelow, and Company, Cambridge. PREFACE. TT will be many years before a complete history -*- of the operations of the armies of the Union can be written ; but that is not a sufficient reason why historical pictures may not now be painted from such materials as have come to hand. This volume, therefore, is a sketch of the operations of the Army of the Potomac from August, 1861, to November, 1862, while commanded by Gener- al McOlellan. To avoid detail, the organization of the army is given in an Appendix. It has not been possible, in a book of this size, to give the movements of regiments ; but the narrative has been limited to the operations of brigades and di- visions. It will be comparatively easy, however, for the reader to ascertain the general position of any regiment in the different battles, by con- sulting the Appendix in connection with the narrative. -

OFFICIAL BULLETIN Penna.' Militia, Delegate to State Constitutional Convention of 76

Ol"l"ICIAL BULLETIN N y k C't N y (35648). Son of Samuel and Aurelia EDWARD DALY WRIGHT, ew or 1 Yd C j- (Wells) Fleming· great-grandson of (Fleming) Wright; grandson of H~nry an • aro t~e f John and 'Mary (Slaymaker) Henr! and ~titia ~~p::k:1onFl:t~~~osgr~!~~:;er:onpr~vate, Lancaster County, Penna. Flemmg, Jr. • great gr f H Sl ker Member Fifth Battalion, Lancaster County, 1t-1ilitia · great'· grandson o enry ayma , . , OFFICIAL BULLETIN Penna.' Militia, Delegate to State Constitutional Convention of 76. ALVIN LESKE WYNNE Philadelphia, Penna. (35464). Son of Samuel ~d Nettle N. ~J--j OF THE Wynne, Jr.; grandso; of Samuel Wynne; great-grandson of_ !~mes ynne; great -gran - son of Jonatluln Wynne, private, Chester County, Penna, Mthtla. y k c· N y (35632) Son of Thomas McKeen and Ida National Society THO:AS BY~UN~~u~=~ gra~~son '~· Wiilia~ and Reb~cca (Goodrich) Baker; great-grandson /YE~-:h e:~d Rachel (Lloyd) Goodrich; great•-grandson of Jol•n !:loyd,. Lieutenant, of the Sons of the American Revolution 0New ~ork Militia and Cont'l Line; greatl..grandson of Miclwel Goodrtch, pnvate, Conn. Militia and Cont'l Troops. R THOMAS RINEK ZULICH, Paterson, N. J. (36015). Son of Henry B. and Emma · (Hesser) Zulicb; grandson of Henry and Margaret (_S_h.oemake~) Hesser; great-grandson of Frederick Hesser. drummer and ~rivate, Penna. Mthtla, pensiOned. President General Orsranized April 30, 1889 WALLACE McCAMANT Incorporated by Northwestern Bank Buildinsr Act of Consrress, June 9, 1906 Portland, Orellon Published at Washinsrton, D. C., in June, October, December, and Marcb. -

Coast Guard Awards CIM 1560 25D(PDF)

Medals and Awards Manual COMDTINST M1650.25D MAY 2008 THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK. Commandant 1900 Half Street, S.W. United States Coast Guard Washington, DC 20593-0001 Staff Symbol: CG-12 Phone: (202) 475-5222 COMDTINST M1650.25D 5 May 2008 COMMANDANT INSTRUCTION M1625.25D Subj: MEDALS AND AWARDS MANUAL 1. PURPOSE. This Manual publishes a revision of the Medals and Awards Manual. This Manual is applicable to all active and reserve Coast Guard members and other Service members assigned to duty within the Coast Guard. 2. ACTION. Area, district, and sector commanders, commanders of maintenance and logistics commands, Commander, Deployable Operations Group, commanding officers of headquarters units, and assistant commandants for directorates, Judge Advocate General, and special staff offices at Headquarters shall ensure that the provisions of this Manual are followed. Internet release is authorized. 3. DIRECTIVES AFFECTED. Coast Guard Medals and Awards Manual, COMDTINST M1650.25C and Coast Guard Rewards and Recognition Handbook, CG Publication 1650.37 are cancelled. 4. MAJOR CHANGES. Major changes in this revision include: clarification of Operational Distinguishing Device policy, award criteria for ribbons and medals established since the previous edition of the Manual, guidance for prior service members, clarification and expansion of administrative procedures and record retention requirements, and new and updated enclosures. 5. ENVIRONMENTAL ASPECTS/CONSIDERATIONS. Environmental considerations were examined in the development of this Manual and have been determined to be not applicable. 6. FORMS/REPORTS: The forms called for in this Manual are available in USCG Electronic Forms on the Standard Workstation or on the Internet: http://www.uscg.mil/forms/, CG Central at http://cgcentral.uscg.mil/, and Intranet at http://cgweb2.comdt.uscg.mil/CGFORMS/Welcome.htm. -

Species at Risk on Department of Defense Installations

Species at Risk on Department of Defense Installations Revised Report and Documentation Prepared for: Department of Defense U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Submitted by: January 2004 Species at Risk on Department of Defense Installations: Revised Report and Documentation CONTENTS 1.0 Executive Summary..........................................................................................iii 2.0 Introduction – Project Description................................................................. 1 3.0 Methods ................................................................................................................ 3 3.1 NatureServe Data................................................................................................ 3 3.2 DOD Installations............................................................................................... 5 3.3 Species at Risk .................................................................................................... 6 4.0 Results................................................................................................................... 8 4.1 Nationwide Assessment of Species at Risk on DOD Installations..................... 8 4.2 Assessment of Species at Risk by Military Service.......................................... 13 4.3 Assessment of Species at Risk on Installations ................................................ 15 5.0 Conclusion and Management Recommendations.................................... 22 6.0 Future Directions............................................................................................. -

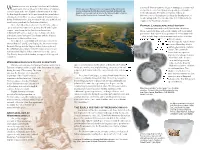

Werowocomoco Was Principal Residence of Powhatan

erowocomoco was principal residence of Powhatan, afterwards Werowocomoco began to emerge as a ceremonial paramount chief of 30-some Indian tribes in Virginia’s A bird’s-eye view of Werowocomoco as it appears today in Gloucester W and political center for Algonquian-speaking communities coastal region at the time English colonists arrived in 1607. County. Bordered by the York River, Leigh Creek (left) and Bland Creek (right), the archaeological site is listed on the National Register of Historic in the Chesapeake. The process of place-making at Archaeological research in the past decade has revealed not Places and the Virginia Historic Landmarks Register. Werowocomoco likely played a role in the development of only that the York River site was a uniquely important place social ranking in the Chesapeake after A.D. 1300 and in the during Powhatan’s time, but also that its role as a political and origins of the Powhatan chiefdom. social center predated the Powhatan chiefdom. More than 60 artifacts discovered at Werowocomoco Power, Landscape and History – projectile points, stone tools, pottery sherds and English Landscapes associated with Amerindian chiefdoms – copper – are shown for the fi rst time at Jamestown that is, regional polities with social ranking and institutional Settlement with archaeological objects from collections governance that organized a population of several thousand of the Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation and the Virginia – often include large-scale or monumental architecture that Department of Historic Resources. transformed space within sacropolitical centers. Developed in cooperation with Werowocomoco site Throughout the Chesapeake region, Native owners Robert F. and C. Lynn Ripley, the Werowocomoco communities constructed boundary ditches Research Group and the Virginia Indian Advisory Board, and enclosures within select towns, marking the exhibition also explores what Werowocomoco means spaces in novel ways. -

Winter 2005-2006

Vol. 23 No. 4 WINTER 2005-2006 PPuullaasskkii AA HHeerroo’’ss FFiinnaall RReesstt Report from the 2005 Board of Managers General Pulaski’s Body by Edward Pinkowski Lecture presented at the Pulaski Museum in Warka, Poland in October 1997 If one may want to know exactly where the work, as was seen in 1853 and 1996, the officers Polish general of the American War of and crew prepared to bury Pulaski's body in Independence died and trace his body from his military uniform with a flag draped over then on, one must start by imagining to be on him. a dirty, smelly, 14-gun privateer, known as the Then the Polish General fell into a vacuum. Wasp, owned by Joseph Atkinson, a merchant Historians didn't pay much attention to of Charleston, South Carolina, and privately Pulaski in America until Jared Sparks, who manned under Captain Samuel Bulfinch, who left the pulpit of a Unitarian church in April, took up sailing in Boston at an early age. One 1823, to edit the North American Review in must also forget most of what was ever said Boston, received a 38-page pamphlet from Paul about this ship. Bentalou, a French captain in the Pulaski For at least two days the black-painted Legion. After reviewing it, Sparks quoted sec- Wasp, sails furled, was tied up at the wooden tions from the pamphlet and tied it with pier of the Bonaventure plantation in Georgia, General Lafayette's return to America at that where Vice Admiral Charles-Henri d'Estaing, time.1 For the next two decades, until he com- who commanded a French squadron of forty- pleted the biography of Pulaski in 1844, Sparks three ships and an army of 4,456 men, set up picked up where Bentalou left off, questioned a field hospital and based his artillery in survivors of the American Revolution, visited September, 1779. -

NALF Fentress SSA U.S. District Court FBI Camp Peary Colonial National

Camp Peary Army Corps Naval of Engineers Weapons Station Yorktown Colonial National SSA Yorktown National Naval Station Historic Park SSA Cemetery/Battlefield Norfolk Cheatham Plum Tree Naval Support Annex USCG U.S. District Island NWR Activity Court Training Center Hampton Roads Yorktown Hampton National Camp Elmore/ Cemetery Camp Allen Ft. Monroe Maritime Administration National NATO SSA National Defense Monument VA Allied Command Reserve Fleet Medical Center Animal & Transformation Plant Health Joint Forces Inspection DEA U.S. District Staff College Service GSA Court Animal & JEB Jefferson Plant Health Little Creek-Ft Story Joint Base Laboratory Inspection Langley-Eustis Service Colonial EEOC National U.S. Customs Historic Park NASA House Veterans Langley GSA Research NOAA Marine USCG Shore Center Center Ops Center Infrastructure FBI USCG Station Jamestown GAO National Atlantic Logistics Center Little Creek Historic Site Hampton Roads Naval Museum ATF Cape Henry USCG Craney Island OPM Memorial Atlantic Area USCG Base Lafayette SSA Portsmouth River Annex Secret USCG GSA U.S. Service 5th District Navy Exchange Additional NOAA Nansemond Customs House St. Helena Command Sites and offices NWR Annex NAS Oceana Joint Staff NRTF LEGEND Animal & St. Juliens Hampton Roads Driver DEA Dept. of the Interior Plant Health Creek Annex Camp Pendleton Dept. of Agriculture Inspection Dam Neck Dept. of Defense Service DOL Area Maritime Office Annex Dept. of Homeland Security Administration Maritime Administration GSA Dept. of Justice SSA Dept. of Energy Dept. of Commerce Naval Medical Back Bay Dept. of Veterans Affairs Farm Center NWR Norfolk Naval NALF Fentress Dept. of Labor Services Portsmouth Shipyard NASA Agency Farm Prepared by: Center Great Dismal Services Naval Support Activity Swamp GSA Agency Northwest Annex Center NWR SSA Updated 11-13 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Colonial National Yorktown National Historic Park Cemetery/Battlefield Plum Tree Island NWR Ft. -

Success Stories

SUCCESS STORIES PLANT NAME AND LOCATION YORK RIVER TREATMENT PLANT (HAMPTON ROADS SANITATION DISTRICT) - YORK RIVER, VA DESIGN DAILY FLOW / PEAK FLOW 0.5 MGD (1893 M3/DAY) / 0.5 MGD (1893 M3/DAY) AQUA-AEROBIC SOLUTION SINGLE-BASIN AquaSBR® SYSTEM, 4-DISK AquaDisk® FILTER AQUA-AEROBIC TECHNOLOGIES CHOSEN FOR FIRST MUNICIPAL- INDUSTRIAL WATER REUSE PROJECT IN VIRGINIA! Hampton Roads Sanitation District (HRSD) was created in 1940 to reduce pollution in the Chesapeake Bay. It currently serves a population of approximately 1.6 million with nine regional wastewater treatment plants in Hampton Roads and four smaller plants on Virginia’s Middle Peninsula. HRSD set the goal to reuse its treated wastewater for nonpotable purposes in the 1980s. An oil refi nery located next to their York River Treatment Plant (YRTP) approached HRSD in 1996 to supply reclaimed water for the refi nery’s cooling and process water. Previously, the refi nery utilized increasingly expensive potable water and upgrading its own treatment facilities was too large an investment. In December 2000, HRSD signed a 20-year agreement to provide the refi nery with 0.5 MGD of reclaimed water. This was Virginia’s fi rst municpal-industrial water reuse project! York River’s AquaSBR® basin in operation. Since the existing activated sludge treatment process at water can be fed to the AquaDisk fi lter from either the full- HRSD’s York River Treatment Plant couldn’t reliably meet the scale plant effl uent or the sidestream AquaSBR system. refi nery’s special target requirements for both low turbidity and year-round ammonia concentration, other treatment HRSD sells the reclaimed water to the refi nery at cost, processes had to be investigated. -

Coast Guard Miniature/Microminiature (2M) Module Test and Repair (Mtr) Program

Commandant US Coast Guard Stop 7710 United States Coast Guard 2703 Martin Luther King Jr Ave SE Washington, DC 20593-7710 Staff Symbol: CG-6811 Phone: (202) 475-3509 Fax: (202) 475-3927 Email: [email protected] COMDTINST 4790.2C 27 NOVEMBER 2018 COMMANDANT INSTRUCTION 4790.2C Subj: COAST GUARD MINIATURE/MICROMINIATURE (2M) MODULE TEST AND REPAIR (MTR) PROGRAM Ref: (a) Certification Manual for Miniature/Microminiature (2M) Module Test and Repair (MTR) Program, NAVSEA TE000-AA-MAN-010/2M (b) Supply Policy and Procedures Manual (SPPM), COMDTINST M4400.19 (series) (c) Naval Engineering Manual, COMDTINST M9000.6 (series) (d) Naval Supply Publication 485 (NAVSUP P-485), Volume I, Afloat Supply (series) (e) Cutter Capital Asset Management Plan (CCAMP), COMDTINST 4700.1 (series) (f) Ordnance Manual, COMDTINST M8000.2 (series) (g) Electronics Manual, COMDTINST M10550.25 (series) 1. PURPOSE. This Instruction defines the maintenance policies and procedures for test and repair of Electronic Assemblies (EAs) and circuit card assemblies (CCAs) contained in Hull, Mechanical, and Electrical (HM&E), Navy-Type/Navy-Owned (NT/NO), Navy-Type/Coast Guard-Owned (NT/CGO) equipment, and applicable Commercial Off the Shelf (COTS) equipment. It applies to Coast Guard (CG) activities involved in the maintenance and material support of this equipment. 2. ACTION. All Coast Guard unit commanders, Commanding Officers, Officers in Charge, Deputy/Assistant Commandants, and Chiefs of Headquarters staff elements must ensure that the provisions of this Instruction are followed. 3. DIRECTIVES AFFECTED. Coast Guard Miniature/Microminiature (2M) Module Test and Repair (MTR) Program, COMDTINST 4790.2B is cancelled. DISTRIBUTION – SDL No.169 a b c d e f g h I j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z A X X X X X X X X X X X X B X X X X X X X X X X X C X X X X D X E X F G X H X X NON-STANDARD DISTRIBUTION: B:a CG-64, CG-6811, CG-41, CG-444, CG-451, CG-9335, CG-751 B:b LANTAREA, PACAREA; B:c (NAVAIR N98), (SPAWAR N2N6),(NAVSEA N96) COMDTINST 4790.2C 4. -

Over 55 Years Ago, the United States Entered World War II. to Most Americans, Now, It’S Something That Happened “Over There” and Is Far Removed from Home

by Mike Prero Over 55 years ago, the United States entered World War II. To most Americans, now, it’s something that happened “over there” and is far removed from home. We frequently read books and see movies about our soldiers in Japanese or German prisoner-of-war camps, but few members of the younger generation realize that between 1942 and 1946, the United States held almost 400,000 German, more than 50,000 Italian, and 5,000 Japanese soldiers in P.O.W. camps right here in the United States. I’ve been a Military collector ever since I entered the hobby, but my interest was really drawn to P.O.W. camps during a game of bridge a number of years ago. Our opponents, an elderly couple, had actually met and fallen in love in a Japanese P.O.W. camp in the Philippines. Fascinating! And so are P.O.W. camp covers. There were over 500 such P.O.W. camps in America during the war. One of them was right down the road from here, in Stockton, CA. Not surprisingly, most were located in the western and central states that had wide-open spaces: California, Texas, Idaho, Arizona, Nebraska, Kansas, Wyoming, etc. Although, there were a few in places like Maryland, Wisconsin, and Michigan. As with most World War II U.S. installations, there are a variety of covers from these P.O.W. camps, although they are definitely scarce compared to the number of camps that existed. I currently have 6,842 U.S. Military covers, but Major P.O.W.