Resolved Stellar Populations As Tracers of Outskirts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Messier Objects

Messier Objects From the Stocker Astroscience Center at Florida International University Miami Florida The Messier Project Main contributors: • Daniel Puentes • Steven Revesz • Bobby Martinez Charles Messier • Gabriel Salazar • Riya Gandhi • Dr. James Webb – Director, Stocker Astroscience center • All images reduced and combined using MIRA image processing software. (Mirametrics) What are Messier Objects? • Messier objects are a list of astronomical sources compiled by Charles Messier, an 18th and early 19th century astronomer. He created a list of distracting objects to avoid while comet hunting. This list now contains over 110 objects, many of which are the most famous astronomical bodies known. The list contains planetary nebula, star clusters, and other galaxies. - Bobby Martinez The Telescope The telescope used to take these images is an Astronomical Consultants and Equipment (ACE) 24- inch (0.61-meter) Ritchey-Chretien reflecting telescope. It has a focal ratio of F6.2 and is supported on a structure independent of the building that houses it. It is equipped with a Finger Lakes 1kx1k CCD camera cooled to -30o C at the Cassegrain focus. It is equipped with dual filter wheels, the first containing UBVRI scientific filters and the second RGBL color filters. Messier 1 Found 6,500 light years away in the constellation of Taurus, the Crab Nebula (known as M1) is a supernova remnant. The original supernova that formed the crab nebula was observed by Chinese, Japanese and Arab astronomers in 1054 AD as an incredibly bright “Guest star” which was visible for over twenty-two months. The supernova that produced the Crab Nebula is thought to have been an evolved star roughly ten times more massive than the Sun. -

CONSTELLATION TRIANGULUM, the TRIANGLE Triangulum Is a Small Constellation in the Northern Sky

CONSTELLATION TRIANGULUM, THE TRIANGLE Triangulum is a small constellation in the northern sky. Its name is Latin for "triangle", derived from its three brightest stars, which form a long and narrow triangle. Known to the ancient Babylonians and Greeks, Triangulum was one of the 48 constellations listed by the 2nd century astronomer Ptolemy. The celestial cartographers Johann Bayer and John Flamsteed catalogued the constellation's stars, giving six of them Bayer designations. The white stars Beta and Gamma Trianguli, of apparent magnitudes 3.00 and 4.00, respectively, form the base of the triangle and the yellow-white Alpha Trianguli, of magnitude 3.41, the apex. Iota Trianguli is a notable double star system, and there are three star systems with planets located in Triangulum. The constellation contains several galaxies, the brightest and nearest of which is the Triangulum Galaxy or Messier 33—a member of the Local Group. The first quasar ever observed, 3C 48, also lies within Triangulum's boundaries. HISTORY AND MYTHOLOGY In the Babylonian star catalogues, Triangulum, together with Gamma Andromedae, formed the constellation known as MULAPIN "The Plough". It is notable as the first constellation presented on (and giving its name to) a pair of tablets containing canonical star lists that were compiled around 1000 BC, the MUL.APIN. The Plough was the first constellation of the "Way of Enlil"—that is, the northernmost quarter of the Sun's path, which corresponds to the 45 days on either side of summer solstice. Its first appearance in the pre-dawn sky (heliacal rising) in February marked the time to begin spring ploughing in Mesopotamia. -

Annual Report 2005

Max Planck Institute t für Astron itu o st m n ie -I k H c e n id la e l P b - e x r a g M M g for Astronomy a r x e b P l la e n id The Max Planck Society c e k H In y s m titu no Heidelberg-Königstuhl te for Astro The Max Planck Society for the Promotion of Sciences was founded in 1948. It operates at present 88 Institutes and other facilities dedicated to basic and applied research. With an annual budget of around 1.4 billion € in the year 2005, the Max Planck Society has about 12 400 employees, of which 4300 are scientists. In addition, annually about 11000 junior and visiting scientists are working at the Institutes of the Max Planck Society. The goal of the Max Planck Society is to promote centers of excellence at the fore- front of the international scientific research. To this end, the Institutes of the Society are equipped with adequate tools and put into the hands of outstanding scientists, who Annual Report have a high degree of autonomy in their scientific work. 2005 Max-Planck-Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Wissenschaften e.V. 2005 Public Relations Office Hofgartenstr. 8 80539 München Tel.: 089/2108-1275 or -1277 Annual Report Fax: 089/2108-1207 Internet: www.mpg.de Max Planck Institute for Astronomie K 4242 K 4243 Dossenheim B 3 D o s s E 35 e n h e N i eckar A5 m e r L a n d L 531 s t r M a a ß nn e he im B e e r r S t tr a a - K 9700 ß B e e n z - S t r a ß e Ziegelhausen Wieblingen Handschuhsheim K 9702 St eu b A656 e n s t B 37 r a E 35 ß e B e In de A5 r r N l kar ec i c M Ne k K 9702 n e a Ruprecht-Karls- ß lierb rh -

MECATX October 2019 Sky Charts Remote Video Astronomy Group

MECATX October 2019 Sky Charts Remote Video Astronomy Group (1) Phoenix (FEE-nix), the Phoenix - October 4 (2) Andromeda (an-DRAH-mih-duh), the Princess of Ethiopia – October 9 (3) Cassiopeia (CASS-ee-uh-PEE-uh), the Queen of Ethiopia – October 9 (4) Cetus (SEE-tus), the Sea Monster (whale) – October 15 (5) Triangulum (try-ANG-gyuh-lum), the Triangle – October 23 (6) Hydrus (HIGH-drus), the Southern Water Snake - October 26 (7) Aries (AIR-eez), the Ram – October 30 Revised by: Alyssa Donnell 09.29.2019 MECA RVA October 2019 - www.mecatx.ning.com – Youtube – MECATX – www.ustream.tv – dfkott October 4 Phoenix (FEE-nix), the Phoenix Phe, Phoenicis (fuh-NICE-iss) MECA RVA October 2018 - www.mecatx.ning.com – Youtube – MECATX – www.ustream.tv – dfkott 1 Phoenix Meaning: The Phoenix Pronunciation: fee' niks Abbreviation: Phe Possessive form: Phoenicis (fen ee' siss) Asterisms: none Bordering constellations: Eridanus, Fornax, Grus, Sculptor, Tucana Overall brightness: 5.753 (64) Central point: RA = 00h54m Dec.= —49° Directional extremes: N = 400 S = —58° E = 2h24m W = 23h24m Messier objects: none Meteor showers: July Phoenicids (14 Jul) December Phoenicids (5 Dec) Midnight culmination date: 4 Oct Bright stars: a (79) Named stars: Ankaa (a) Near stars: L 362-81 (121) Size: 469.32 square degrees (1.138% of the sky) Rank in size: 37 Solar conjunction date: 5 Apr Visibility: completely visible from latitudes: S of +32° completely invisible from latitudes: N of +50° Visible stars: (number of stars brighter than magnitude 5.5): 27 Interesting facts: (1) This is one of 11 constellations invented by Pieter Dirksz Keyser and Frederick de Houtman, during the years 1595-7. -

Three Naked Eye Galaxies? Dave Eagle

Three Naked Eye Galaxies? Dave Eagle. Eagleseye Observatory. Star hopping to M31, The Great Andromeda Galaxy. In the autumn sky in the northern hemisphere, the constellations of Perseus and Andromeda are very proudly on display, located on the meridian around midnight, and visible from most of the world. The Great Square of Pegasus is a distinct asterism of four stars. Using just your naked eye, find this square of stars. Incidentally, the top left star (all instructions are now as seen from the northern hemisphere) Sirrah, is now actually Alpha Andromedae. From this square of stars take the top edge of the square and carry the line on towards the left (east) and up. Just under half the distance of the top of the square, you should come to another reasonably bright star. Slightly left and up again, taking a slightly longer journey, you will come to another star of similar brightness. This is Mirach or Beta Andromedae. When you have found this star, turn 90 degrees to the right. You will then see two fairly bright stars leading away. Aim for the second star and gaze at this star. If your skies are reasonably dark, just above and to the right of the second star you should be able to see a faint smudge. This marks the location of M31, The Andromeda Galaxy. In five hops we have found our quarry. Figure 1 – Star hopping from Sirrah to The Andromeda Galaxy. This is the most distant object you can see with the naked eye and is almost 2.5 million light years away. -

The Messier Catalog

The Messier Catalog Messier 1 Messier 2 Messier 3 Messier 4 Messier 5 Crab Nebula globular cluster globular cluster globular cluster globular cluster Messier 6 Messier 7 Messier 8 Messier 9 Messier 10 open cluster open cluster Lagoon Nebula globular cluster globular cluster Butterfly Cluster Ptolemy's Cluster Messier 11 Messier 12 Messier 13 Messier 14 Messier 15 Wild Duck Cluster globular cluster Hercules glob luster globular cluster globular cluster Messier 16 Messier 17 Messier 18 Messier 19 Messier 20 Eagle Nebula The Omega, Swan, open cluster globular cluster Trifid Nebula or Horseshoe Nebula Messier 21 Messier 22 Messier 23 Messier 24 Messier 25 open cluster globular cluster open cluster Milky Way Patch open cluster Messier 26 Messier 27 Messier 28 Messier 29 Messier 30 open cluster Dumbbell Nebula globular cluster open cluster globular cluster Messier 31 Messier 32 Messier 33 Messier 34 Messier 35 Andromeda dwarf Andromeda Galaxy Triangulum Galaxy open cluster open cluster elliptical galaxy Messier 36 Messier 37 Messier 38 Messier 39 Messier 40 open cluster open cluster open cluster open cluster double star Winecke 4 Messier 41 Messier 42/43 Messier 44 Messier 45 Messier 46 open cluster Orion Nebula Praesepe Pleiades open cluster Beehive Cluster Suburu Messier 47 Messier 48 Messier 49 Messier 50 Messier 51 open cluster open cluster elliptical galaxy open cluster Whirlpool Galaxy Messier 52 Messier 53 Messier 54 Messier 55 Messier 56 open cluster globular cluster globular cluster globular cluster globular cluster Messier 57 Messier -

DGSAT: Dwarf Galaxy Survey with Amateur Telescopes

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. arxiv30539 c ESO 2017 March 21, 2017 DGSAT: Dwarf Galaxy Survey with Amateur Telescopes II. A catalogue of isolated nearby edge-on disk galaxies and the discovery of new low surface brightness systems C. Henkel1;2, B. Javanmardi3, D. Mart´ınez-Delgado4, P. Kroupa5;6, and K. Teuwen7 1 Max-Planck-Institut f¨urRadioastronomie, Auf dem H¨ugel69, 53121 Bonn, Germany 2 Astronomy Department, Faculty of Science, King Abdulaziz University, P.O. Box 80203, Jeddah 21589, Saudi Arabia 3 Argelander Institut f¨urAstronomie, Universit¨atBonn, Auf dem H¨ugel71, 53121 Bonn, Germany 4 Astronomisches Rechen-Institut, Zentrum f¨urAstronomie, Universit¨atHeidelberg, M¨onchhofstr. 12{14, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany 5 Helmholtz Institut f¨ur Strahlen- und Kernphysik (HISKP), Universit¨at Bonn, Nussallee 14{16, D-53121 Bonn, Germany 6 Charles University, Faculty of Mathematics and Physics, Astronomical Institute, V Holeˇsoviˇck´ach 2, CZ-18000 Praha 8, Czech Republic 7 Remote Observatories Southern Alps, Verclause, France Received date ; accepted date ABSTRACT The connection between the bulge mass or bulge luminosity in disk galaxies and the number, spatial and phase space distribution of associated dwarf galaxies is a dis- criminator between cosmological simulations related to galaxy formation in cold dark matter and generalised gravity models. Here, a nearby sample of isolated Milky Way- class edge-on galaxies is introduced, to facilitate observational campaigns to detect the associated families of dwarf galaxies at low surface brightness. Three galaxy pairs with at least one of the targets being edge-on are also introduced. Approximately 60% of the arXiv:1703.05356v2 [astro-ph.GA] 19 Mar 2017 catalogued isolated galaxies contain bulges of different size, while the remaining objects appear to be bulgeless. -

The Messier Marathon Search Sequence

2/28/2020 Messier Marathon Search Sequence List This file presents the Messier objects in the order of the Marathon Search Sequence given by Don Machholz in his Messier Marathon Observer's Guide. The Messier Marathon Search Sequence compiled online by Hartmut Frommert, using work of Don Machholz. Depending on geographic location, it may be impossible to find them all, and may be better to slightly modify this list. In case of doubt consult Don Machholz's book. This list should be good for northern latitudes 20 to 40. 1. M77 spiral galaxy in Cetus 2. M74 spiral galaxy in Pisces 3. M33 The Triangulum Galaxy (also Pinwheel) spiral galaxy in Triangulum 4. M31 The Andromeda Galaxy spiral galaxy in Andromeda 5. M32 Satellite galaxy of M31 elliptical galaxy in Andromeda 6. M110 Satellite galaxy of M31 elliptical galaxy in Andromeda 7. M52 open cluster in Cassiopeia 8. M103 open cluster in Cassiopeia 9. M76 The Little Dumbell, Cork, or Butterfly planetary nebula in Perseus 10. M34 open cluster in Perseus 11. M45 Subaru, the Pleiades--the Seven Sisters open cluster in Taurus 12. M79 globular cluster in Lepus 13. M42 The Great Orion Nebula diffuse nebula in Orion 14. M43 part of the Orion Nebula (de Mairan's Nebula) diffuse nebula in Orion 15. M78 diffuse reflection nebula in Orion 16. M1 The Crab Nebula supernova remnant in Taurus 17. M35 open cluster in Gemini 18. M37 open cluster in Auriga 19. M36 open cluster in Auriga 20. M38 open cluster in Auriga 21. M41 open cluster in Canis Major 22. -

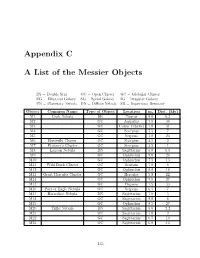

Appendix C a List of the Messier Objects

Appendix C A List of the Messier Objects DS=DoubleStar OC=OpenCluster GC=GlobularCluster EG = Elliptical Galaxy SG = Spiral Galaxy IG = Irregular Galaxy PN = Planetary Nebula DN = Diffuse Nebula SR = Supernova Remnant Object Common Name Type of Object Location mv Dist. (kly) M1 Crab Nebula SR Taurus 9.0 6.3 M2 GC Aquarius 7.5 36 M3 GC Canes Venatici 7.0 31 M4 GC Scorpius 7.5 7 M5 GC Serpens 7.0 23 M6 Butterfly Cluster OC Scorpius 4.5 2 M7 Ptolemy’s Cluster OC Scorpius 3.5 1 M8 Lagoon Nebula DN Sagittarius 5.0 6.5 M9 GC Ophiuchus 9.0 26 M10 GC Ophiuchus 7.5 13 M11 Wild Duck Cluster OC Scutum 7.0 6 M12 GC Ophiuchus 8.0 18 M13 Great Hercules Cluster GC Hercules 5.8 22 M14 GC Ophiuchus 9.5 27 M15 GC Pegasus 7.5 33 M16 Part of Eagle Nebula OC Serpens 6.5 7 M17 Horseshoe Nebula DN Sagittarius 7.0 5 M18 OC Sagittarius 8.0 6 M19 GC Ophiuchus 8.5 27 M20 Trifid Nebula DN Sagittarius 5.0 2.2 M21 OC Sagittarius 7.0 3 M22 GC Sagittarius 6.5 10 M23 OC Sagittarius 6.0 4.5 135 Object Common Name Type of Object Location mv Dist. (kly) M24 Milky Way Patch Star cloud Sagittarius 11.5 10 M25 OC Sagittarius 4.9 2 M26 OC Scutum 9.5 5 M27 Dumbbell Nebula PN Vulpecula 7.5 1.25 M28 GC Sagittarius 8.5 18 M29 OC Cygnus 9.0 7.2 M30 GC Capricornus 8.5 25 M31 Andromeda Galaxy SG Andromeda 3.5 2500 M32 Satellite galaxy of M31 EG Andromeda 10.0 2900 M33 Triangulum Galaxy SG Triangulum 7.0 2590 M34 OC Perseus 6.0 1.4 M35 OC Gemini 5.5 2.8 M36 OC Auriga 6.5 4.1 M37 OC Auriga 6.0 4.6 M38 OC Auriga 7.0 4.2 M39 OC Cygnus 5.5 0.3 M40 Winnecke 4 DS Ursa Major 9.0 M41 OC Canis -

Galaxy Group and Cluster Astronomy at RIT

Galaxy Group and Cluster Astronomy at RIT 23 Spitzer,)HST,)GALEX,)&)Chandra)Image) Green Bank 100M Hershel 3.5M Credit:)NRAO) Credit:)Chicago)University) Hubble Space Telescope (HST) Sloan Digital 2.4M Sky Survey 2.5M Credit:) Hubblesite ) In Space On Earth Astronomers at RIT want to learn about galaxy groups and clusters. They use a variety of ground- and space-based telescopes. 24 YOU ARE HERE Milky Way galaxy Artist’s representation Here’s where the sun lives! We are on the outskirts of the Milky Way. It takes the sun 200 million years to travel once around the galaxy. Credit:)NASA/JPLJCaltech/R) 25 Sometimes galaxies run past each other or even combine! ZOOM Antennae Galaxies This can jumpstart star formation and make irregularly shaped galaxies like the ones shown here. 26 Credit:)HubbleSite) Living as a group of galaxies, the Milky Way has neighbors: the larger Andromeda and the smaller Tr i a n g u l u m . The Milky Way s Home The Local Group Andromeda Galaxy This is an artist’s interpretation. NGC185 Not drawn to scale. NGC147 M32 Tr i a n g u l u m Galaxy NGC205 Pegasus Milky Way Galaxy IC1613 Draco Fornax WLM Ursa Minor Sculptor LEo I Leo II Sextans NGC6822 SMC LMC Carina Artist’s representation of the Local Group Around each larger galaxy there are dozens of dwarf galaxies. It takes light 2.5 million years to get to Earth from Andromeda. 27 Hundreds, or even thousands, of galaxies can live together in a cluster. A crowded neighborhood Abell 1689 shown here has over 2000 galaxies living far, far away from Earth. -

Messier Object Mapping System

Messier Object Mapping System Messier Object Constellation Map# Messier Object Constellation Map# M1 Taurus 1-6 M56 Lyra 3 M2 Aquarius 8 M57 Lyra 3 M3 Canes Venatici 4-10 M58 Virgo IN2-5 M4 Scorpius 2 M59 Virgo IN2 M5 Scorpius 10 M60 Virgo IN2-5-9-10 M6 Scorpius 2 M61 Virgo IN2-5-8 M7 Scorpius 2 M62 Ophiuchus 2 M8 Sagittarius 2-IN1 M63 Canes Venatici 4 M9 Ophiuchus 2 M64 Coma Berenices 4-5 M10 Ophiuchus 2 M65 Leo 5 M11 Scutum 2 M66 Leo 5 M12 Ophiuchus 2 M67 Cancer 6 M13 Hercules 3 M68 Hydra 9 M14 Ophiuchus 2 M69 Sagittarius 2-IN1-8 M15 Pegasus 8 M70 Sagittarius 2-IN1-8 M16 Serpens 2-IN1 M71 Sagittarius 2 M17 Sagittarius 2-IN1 M72 Aquarius 8 M18 Sagittarius 2-IN1 M73 Aquarius 8 M19 Ophiuchus 2 M74 Pisces 11 M20 Sagittarius 2-IN1-8 M75 Sagittarius 8 M21 Sagittarius 2-IN1-8 M76 Perseus 7 M22 Sagittarius 2-IN1-8 M77 Cetus 11 M23 Sagittarius 2-IN1 M78 Orion 1 M24 Sagittarius 2-IN1 M79 Lepus 1 M25 Sagittarius 2-IN1-8 M80 Scorpius 2 M26 Scutum 2 M81 Ursa Major 4 M27 Vupecula 3 M82 Ursa Major 4 M28 Sagittarius 2-IN1-8 M83 Hydra 9 M29 Cygnus 3 M84 Virgo IN2-5 M30 Capricornus 8 M85 Coma Berenices 4-5 M31 Andromeda 7-11 M86 Virgo IN2-5 M32 Andromeda 7-11 M87 Virgo IN2-5 M33 Triangulum 7-11 M88 Coma Berenices IN2-5 M34 Perseus 7-11 M89 Virgo IN2 M35 Gemini 1-6 M90 Virgo IN2-5 M36 Auriga 1-6 M91 Virgo IN2-5 M37 Auriga 1-6 M92 Hercules 3 M38 Auriga 1 M93 Puppis 1-6 M39 Cygnus 3-7 M94 Canes Venatici 4-5 M40 Ursa Major 4 M95 Leo 5 M41 Canis Major 1 M96 Leo 5 M42 Orion 1 M97 Ursa Major 4 M43 Orion 1 M98 Coma Berenices IN2-4-5 M44 Sagittarius 6 M99 Coma Berenices IN2-4-5 M45 Taurus 1-11 M100 Coma Berenices IN2-4-5 M46 Puppis 1-6 M101 Ursa Major 4 M47 Puppis 1-6 M102 Draco 4 M48 Hydra 6 M103 Cassiopeia 7 M49 Virgo 2-IN1-8 M104 Virgo 5-9-10 M50 Monoceros 1-6 M105 Leo 5 M51 Canes Venatici 4-10 M106 Canes Venatici 4-5 M52 Cassiopeia 7 M107 Ophiuchus 2 M53 Coma Berenices 4-5-10 M108 Ursa Major 4 M54 Sagittarius 2-IN1-8 M109 Ursa Major 4-5 M55 Sagittarius 2-8 M110 Andromeda 7-11 Messier Object List # NGC# Constellation Type Name, If Any Mag. -

September 1 2 3 4 2021

Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday September 1 2 3 4 2021 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Venus 4.1°S Moon 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Saturn 3.8°N Moon Jupiter 4.0°N Moon Helix Nebula NGC 7293 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 NASA, ESA, and C.R. O'Dell (Vanderbilt University) 4 Beehive 2.9°S of Moon 6 Mercury at Aphelion 26 27 28 29 30 11 Moon at Perigee: 368464 km 12 Moon at Descending Node 14 Mercury at Greatest Elong: 26.8°E 14 Neptune at Opposition 22 Autumnal Equinox Suggested DSOs for this month 26 Moon at Ascending Node 50mm-500mm 50mm-500mm 135mm-1250mm 135mm-1250mm 200mm-2000mm 300mm-2700mm 750mm-4000mm 26 Moon at Apogee: 404641 km Andromeda Galaxy Elephant Trunk Triangulum Galaxy Pacman Nebula The Hidden Galaxy Sculptor Galaxy Phantom Galaxy 30 Pollux 2.8°N of Moon 420mm-2800mm 700mm-4000mm 50mm-420mm 85mm-600mm 1200mm-4000mm 750mm-4000mm 500mm-4000mm Helix Nebula Dumbbel Nebula Heart Nebula Soul Nebula Nautilus Galaxy Galaxy NGC 891 Barred Spiral Galaxy Credits Andromeda Galaxy M31 All images in this calendar are the property of their respective owners and https://www.astrobin.com/55421/ Raúl López, Skyman have been used either with their permission or respecting their use license. All rights reserved --- The images of Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Neptune, Uranus and Moon Elephant Trunk IC 1396 https://www.astrobin.com/rl2rcs/ have been obtained from the posters of the "Solar System and Beyond Poster Set" Raúl López, Skyman https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/resources/925/solar-system-and-beyond-poster-set/ All rights reserved --- Triangulum Galaxy M33 The image of the Sun has been obtained from the Solar Dynamics Observatory https://www.flickr.com/photos/rvr/50391788676 https://sdo.gsfc.nasa.gov/ Víctor R.