History of Captive Management and Conservation Amphibian Programs Mostly in Zoos and Aquariums

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gibbs Thesis Final Revised Final

Species Declines: Examining patterns of species distribution, abundance, variability and conservation status in relation to anthropogenic activities Mary Katherine Elizabeth Gibbs Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the PhD degree in the Ottawa-Carleton Institute of Biology Thèse soumise à la Faculté des étude supérieures et postdoctorales Université d’Ottawa en vue de l’obtention du doctorat de L’institut de biologie d’Ottawa-Carleton Department of Biology Faculty of Science University of Ottawa © Mary Katherine Elizabeth Gibbs, Ottawa, Canada, 2012 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my supervisor, Dr. David Currie. Most importantly, you gave me the freedom to work on questions that I’m passionate about. You never stopped challenging me and always asked that I push a little bit farther. I really think your commitment to scientific rigor goes above and beyond the average. And thank you for the many, many cups of tea over the years. My committee members, Dr. Scott Findlay and Dr. Mark Forbes, your feedback made this a better thesis. Scott, thank you for being scary enough to motivate me to always bring my A-game, and for providing endless new words to look up in the dictionary. By the end of this, I may actually know what ‘epistemological’ means. I would also like to thank Dr. Jeremy Kerr for his insight and not being afraid to be a scientist and an advocate. I need to thank all the lab mates that have come and gone and added so much to the last six years. -

Conserving the Hip Hoppers: Amphibian Research at Greater Manchester Universities

REVIEW ARTICLE The Herpetological Bulletin 135, 2016: 1-3 Conserving the hip hoppers: Amphibian research at Greater Manchester Universities ROBERT JEHLE1*, RACHAEL ANTWIS1 & RICHARD PREZIOSI2 1School of Environment and Life Sciences, University of Salford, M5 4WT Salford, UK 2Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Manchester, M13 9PT Manchester, UK *Corresponding author Email: [email protected] Characterising Greater Manchester is not an easy task. As a hotbed of radical ideas, the rise of Greater Manchester during the industrial revolution was followed by a significant economic and population decline. As one of the fastest-growing regions in the United Kingdom of the 21st century, contemporary Greater Manchester is shaped by a conglomerate of different influences. The dynamic history of the area is also reflected in emerging herpetological research activities. Without a pronounced tradition in organismal herpetology, Greater Manchester has recently developed into a national hotspot for academic research on amphibian conservation. Perhaps most importantly, the emerged activities are largely shaped through efforts led by postgraduate students. The present overview summarises Figure 1. Participants of the 2015 Amphibian Conservation these developments. Research Symposium in Cambridge. The conference series A main home of amphibian research activities in Greater started in Manchester in 2012. Manchester is represented by the Manchester Amphibian Research Group (MARG, http://amphibianresearch.org), with a main goal to “advance both ex situ and in situ amphibian conservation through evidence-based research”. Table 1. Amphibian conservation-related research outputs The first MARG meeting took place at the University (indexed journal articles) produced at Greater Manchester of Manchester in 2010, and convened the principal Universities since the first MARG meeting in 2010. -

Managing Diversity in the Riverina Rice Fields—

Reconciling Farming with Wildlife —Managing diversity in the Riverina rice fields— RIRDC Publication No. 10/0007 RIRDCInnovation for rural Australia Reconciling Farming with Wildlife: Managing Biodiversity in the Riverina Rice Fields by J. Sean Doody, Christina M. Castellano, Will Osborne, Ben Corey and Sarah Ross April 2010 RIRDC Publication No 10/007 RIRDC Project No. PRJ-000687 © 2010 Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation. All rights reserved. ISBN 1 74151 983 7 ISSN 1440-6845 Reconciling Farming with Wildlife: Managing Biodiversity in the Riverina Rice Fields Publication No. 10/007 Project No. PRJ-000687 The information contained in this publication is intended for general use to assist public knowledge and discussion and to help improve the development of sustainable regions. You must not rely on any information contained in this publication without taking specialist advice relevant to your particular circumstances. While reasonable care has been taken in preparing this publication to ensure that information is true and correct, the Commonwealth of Australia gives no assurance as to the accuracy of any information in this publication. The Commonwealth of Australia, the Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation (RIRDC), the authors or contributors expressly disclaim, to the maximum extent permitted by law, all responsibility and liability to any person, arising directly or indirectly from any act or omission, or for any consequences of any such act or omission, made in reliance on the contents of this publication, whether or not caused by any negligence on the part of the Commonwealth of Australia, RIRDC, the authors or contributors. The Commonwealth of Australia does not necessarily endorse the views in this publication. -

Anura, Rhacophoridae)

Zoologica Scripta Patterns of reproductive-mode evolution in Old World tree frogs (Anura, Rhacophoridae) MADHAVA MEEGASKUMBURA,GAYANI SENEVIRATHNE,S.D.BIJU,SONALI GARG,SUYAMA MEEGASKUMBURA,ROHAN PETHIYAGODA,JAMES HANKEN &CHRISTOPHER J. SCHNEIDER Submitted: 3 December 2014 Meegaskumbura, M., Senevirathne, G., Biju, S. D., Garg, S., Meegaskumbura, S., Pethiya- Accepted: 7 May 2015 goda, R., Hanken, J., Schneider, C. J. (2015). Patterns of reproductive-mode evolution in doi:10.1111/zsc.12121 Old World tree frogs (Anura, Rhacophoridae). —Zoologica Scripta, 00, 000–000. The Old World tree frogs (Anura: Rhacophoridae), with 387 species, display a remarkable diversity of reproductive modes – aquatic breeding, terrestrial gel nesting, terrestrial foam nesting and terrestrial direct development. The evolution of these modes has until now remained poorly studied in the context of recent phylogenies for the clade. Here, we use newly obtained DNA sequences from three nuclear and two mitochondrial gene fragments, together with previously published sequence data, to generate a well-resolved phylogeny from which we determine major patterns of reproductive-mode evolution. We show that basal rhacophorids have fully aquatic eggs and larvae. Bayesian ancestral-state reconstruc- tions suggest that terrestrial gel-encapsulated eggs, with early stages of larval development completed within the egg outside of water, are an intermediate stage in the evolution of ter- restrial direct development and foam nesting. The ancestral forms of almost all currently recognized genera (except the fully aquatic basal forms) have a high likelihood of being ter- restrial gel nesters. Direct development and foam nesting each appear to have evolved at least twice within Rhacophoridae, suggesting that reproductive modes are labile and may arise multiple times independently. -

Character Assessment, Genus Level Boundaries, and Phylogenetic Analyses of the Family Rhacophoridae: a Review and Present Day Status

Contemporary Herpetology ISSN 1094-2246 2000 Number 2 7 April 2000 CHARACTER ASSESSMENT, GENUS LEVEL BOUNDARIES, AND PHYLOGENETIC ANALYSES OF THE FAMILY RHACOPHORIDAE: A REVIEW AND PRESENT DAY STATUS Jeffery A. Wilkinson ([email protected]) and Robert C. Drewes ([email protected]) Department of Herpetology, California Academy of Sciences, Golden Gate Park, San Francisco, California 94118 Abstract. The first comprehensive phylogenetic analysis of the family Rhacophoridae was conducted by Liem (1970) scoring 81 species for 36 morphological characters. Channing (1989), in a reanalysis of Liem’s study, produced a phylogenetic hypothesis different from that of Liem. We compared the two studies and produced a third phylogenetic hypothesis based on the same characters. We also present the synapomorphic characters from Liem that define the major clades and each genus within the family. Finally, we summarize intergeneric relationships within the family as hypothesized by other studies, and the family’s current status as it relates to other ranoid families. The family Rhacophoridae is comprised of over 200 species of Asian and African tree frogs that have been categorized into 10 genera and two subfamilies (Buergerinae and Rhacophorinae; Duellman, 1993). Buergerinae is a monotypic category that accommodates the relatively small genus Buergeria. The remaining genera, Aglyptodactylus, Boophis, Chirixalus, Chiromantis, Nyctixalus, Philautus, Polyp edates, Rhacophorus, and Theloderma, comprise Rhacophorinae (Channing, 1989). The family is part of the neobatrachian clade Ranoidea, which also includes the families Ranidae, Hyperoliidae, Dendrobatidae, Arthroleptidae, the genus Hemisus, and possibly the family Microhylidae. The Ranoidea clade is distinguished from other neobatrachians by the synapomorphic characters of completely fused epicoracoid cartilages, the medial end of the coracoid being wider than the lateral end, and the insertion of the semitendinosus tendon being dorsal to the m. -

Amphibian Alliance for Zero Extinction Sites in Chiapas and Oaxaca

Amphibian Alliance for Zero Extinction Sites in Chiapas and Oaxaca John F. Lamoreux, Meghan W. McKnight, and Rodolfo Cabrera Hernandez Occasional Paper of the IUCN Species Survival Commission No. 53 Amphibian Alliance for Zero Extinction Sites in Chiapas and Oaxaca John F. Lamoreux, Meghan W. McKnight, and Rodolfo Cabrera Hernandez Occasional Paper of the IUCN Species Survival Commission No. 53 The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN or other participating organizations. Published by: IUCN, Gland, Switzerland Copyright: © 2015 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation: Lamoreux, J. F., McKnight, M. W., and R. Cabrera Hernandez (2015). Amphibian Alliance for Zero Extinction Sites in Chiapas and Oaxaca. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN. xxiv + 320pp. ISBN: 978-2-8317-1717-3 DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.CH.2015.SSC-OP.53.en Cover photographs: Totontepec landscape; new Plectrohyla species, Ixalotriton niger, Concepción Pápalo, Thorius minutissimus, Craugastor pozo (panels, left to right) Back cover photograph: Collecting in Chamula, Chiapas Photo credits: The cover photographs were taken by the authors under grant agreements with the two main project funders: NGS and CEPF. -

Amphibiaweb's Illustrated Amphibians of the Earth

AmphibiaWeb's Illustrated Amphibians of the Earth Created and Illustrated by the 2020-2021 AmphibiaWeb URAP Team: Alice Drozd, Arjun Mehta, Ash Reining, Kira Wiesinger, and Ann T. Chang This introduction to amphibians was written by University of California, Berkeley AmphibiaWeb Undergraduate Research Apprentices for people who love amphibians. Thank you to the many AmphibiaWeb apprentices over the last 21 years for their efforts. Edited by members of the AmphibiaWeb Steering Committee CC BY-NC-SA 2 Dedicated in loving memory of David B. Wake Founding Director of AmphibiaWeb (8 June 1936 - 29 April 2021) Dave Wake was a dedicated amphibian biologist who mentored and educated countless people. With the launch of AmphibiaWeb in 2000, Dave sought to bring the conservation science and basic fact-based biology of all amphibians to a single place where everyone could access the information freely. Until his last day, David remained a tirelessly dedicated scientist and ally of the amphibians of the world. 3 Table of Contents What are Amphibians? Their Characteristics ...................................................................................... 7 Orders of Amphibians.................................................................................... 7 Where are Amphibians? Where are Amphibians? ............................................................................... 9 What are Bioregions? ..................................................................................10 Conservation of Amphibians Why Save Amphibians? ............................................................................. -

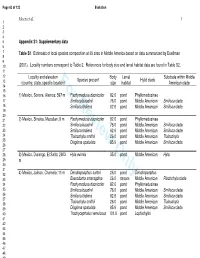

For Review Only

Page 63 of 123 Evolution Moen et al. 1 1 2 3 4 5 Appendix S1: Supplementary data 6 7 Table S1 . Estimates of local species composition at 39 sites in Middle America based on data summarized by Duellman 8 9 10 (2001). Locality numbers correspond to Table 2. References for body size and larval habitat data are found in Table S2. 11 12 Locality and elevation Body Larval Subclade within Middle Species present Hylid clade 13 (country, state, specific location)For Reviewsize Only habitat American clade 14 15 16 1) Mexico, Sonora, Alamos; 597 m Pachymedusa dacnicolor 82.6 pond Phyllomedusinae 17 Smilisca baudinii 76.0 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 18 Smilisca fodiens 62.6 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 19 20 21 2) Mexico, Sinaloa, Mazatlan; 9 m Pachymedusa dacnicolor 82.6 pond Phyllomedusinae 22 Smilisca baudinii 76.0 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 23 Smilisca fodiens 62.6 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 24 Tlalocohyla smithii 26.0 pond Middle American Tlalocohyla 25 Diaglena spatulata 85.9 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 26 27 28 3) Mexico, Durango, El Salto; 2603 Hyla eximia 35.0 pond Middle American Hyla 29 m 30 31 32 4) Mexico, Jalisco, Chamela; 11 m Dendropsophus sartori 26.0 pond Dendropsophus 33 Exerodonta smaragdina 26.0 stream Middle American Plectrohyla clade 34 Pachymedusa dacnicolor 82.6 pond Phyllomedusinae 35 Smilisca baudinii 76.0 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 36 Smilisca fodiens 62.6 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 37 38 Tlalocohyla smithii 26.0 pond Middle American Tlalocohyla 39 Diaglena spatulata 85.9 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 40 Trachycephalus venulosus 101.0 pond Lophiohylini 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Evolution Page 64 of 123 Moen et al. -

Pedal Luring in the Leaf-Frog Phyllomedusa Burmeisteri (Anura, Hylidae, Phyllomedusinae)

Phyllomedusa 1(2):93-95, 2002 © 2002 Melopsittacus Publicações Científicas ISSN 1519-1397 Pedal luring in the leaf-frog Phyllomedusa burmeisteri (Anura, Hylidae, Phyllomedusinae) Jaime Bertoluci Departamento de Zoologia, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais. Caixa Postal 486, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil, 31270-901. E-mail: [email protected]. Keywords - Phyllomedusa burmeisteri, Phyllomedusinae, Hylidae, Anura, pedal luring, prey capture, feeding behavior. Luring behavior as a strategy of prey cap- the frog was maintained in a 60 × 30 × 37-cm ture has evolved independently in several glass terrarium containing soil and a bromeliad. squamate lineages, including pygopodid lizards On the fourth day of acclimation at 2300 h and (Murray et al. 1991), and boid (Murphy et al. under dim light, pedal luring was observed in 1978, Radcliffe et al. 1980), viperid (Greene response to offering the frog an individual adult and Campbell 1972, Heatwole and Dawson cricket (Orthoptera); the same observations were 1976, Henderson 1970, Sazima 1991), elapid made the next night. During the next three days, (Carpenter et al. 1978), and colubrid snakes the frog fed on domestic cockroaches (Sazima and Puorto 1993). Bavetz (1994) (Blattaria), but pedal luring was not observed in reported pedal luring related to predation in these circumstances. Larval mealworms ambystomatid salamanders. In anurans, this (Tenebrio sp.) also were offered to the frog, but feeding behavior has been described only for the always were refused. terrestrial leptodactylid frogs Ceratophrys Phyllomedusa burmeisteri is a sit-and-wait calcarata (Murphy 1976) and C. ornata predator that typically perches with its hands (Radcliffe et al. 1986). Pedal luring apparently and feet firmly grasping the substrate while does not occur in the terrestrial leptodactylids searching for prey. -

Near the Himalayas, from Kashmir to Sikkim, at Altitudes the Catholic Inquisition, and the Traditional Use of These of up to 2700 Meters

Year of edition: 2018 Authors of the text: Marc Aixalà & José Carlos Bouso Edition: Alex Verdaguer | Genís Oña | Kiko Castellanos Illustrations: Alba Teixidor EU Project: New Approaches in Harm Reduction Policies and Practices (NAHRPP) Special thanks to collaborators Alejandro Ponce (in Peyote report) and Eduardo Carchedi (in Kambó report). TECHNICAL REPORT ON PSYCHOACTIVE ETHNOBOTANICALS Volumes I - II - III ICEERS International Center for Ethnobotanical Education Research and Service INDEX SALVIA DIVINORUM 7 AMANITA MUSCARIA 13 DATURA STRAMONIUM 19 KRATOM 23 PEYOTE 29 BUFO ALVARIUS 37 PSILOCYBIN MUSHROOMS 43 IPOMOEA VIOLACEA 51 AYAHUASCA 57 IBOGA 67 KAMBÓ 73 SAN PEDRO 79 6 SALVIA DIVINORUM SALVIA DIVINORUM The effects of the Hierba Pastora have been used by Mazatec Indians since ancient times to treat diseases and for divinatory purposes. The psychoactive compound Salvia divinorum contains, Salvinorin A, is the most potent naturally occurring psychoactive substance known. BASIC INFO Ska Pastora has been used in divination and healing Salvia divinorum is a perennial plant native to the Maza- rituals, similar to psilocybin mushrooms. Maria Sabina tec areas of the Sierra Madre Oriental Mountains of Mexi- told Wasson and Hofmann (the discoverers of its Mazatec co. Its habitat is tropical forests, where it grows between usage) that Salvia divinorum was used in times when the- 300 and 800 meters above sea level. It belongs to the re was a shortage of mushrooms. Some sources that have Lamiaceae family, and is mainly reproduced by cuttings done later feldwork point out that the use of S. divinorum since it rarely produces seeds. may be more widespread than originally believed, even in times when mushrooms were abundant. -

The Most Frog-Diverse Place in Middle America, with Notes on The

Offcial journal website: Amphibian & Reptile Conservation amphibian-reptile-conservation.org 13(2) [Special Section]: 304–322 (e215). The most frog-diverse place in Middle America, with notes on the conservation status of eight threatened species of amphibians 1,2,*José Andrés Salazar-Zúñiga, 1,2,3Wagner Chaves-Acuña, 2Gerardo Chaves, 1Alejandro Acuña, 1,2Juan Ignacio Abarca-Odio, 1,4Javier Lobon-Rovira, 1,2Edwin Gómez-Méndez, 1,2Ana Cecilia Gutiérrez-Vannucchi, and 2Federico Bolaños 1Veragua Foundation for Rainforest Research, Limón, COSTA RICA 2Escuela de Biología, Universidad de Costa Rica, San Pedro, 11501-2060 San José, COSTA RICA 3División Herpetología, Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales ‘‘Bernardino Rivadavia’’-CONICET, C1405DJR, Buenos Aires, ARGENTINA 4CIBIO Research Centre in Biodiversity and Genetic Resources, InBIO, Universidade do Porto, Campus Agrário de Vairão, Rua Padre Armando Quintas 7, 4485-661 Vairão, Vila do Conde, PORTUGAL Abstract.—Regarding amphibians, Costa Rica exhibits the greatest species richness per unit area in Middle America, with a total of 215 species reported to date. However, this number is likely an underestimate due to the presence of many unexplored areas that are diffcult to access. Between 2012 and 2017, a monitoring survey of amphibians was conducted in the Central Caribbean of Costa Rica, on the northern edge of the Matama mountains in the Talamanca mountain range, to study the distribution patterns and natural history of species across this region, particularly those considered as endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. The results show the highest amphibian species richness among Middle America lowland evergreen forests, with a notable anuran representation of 64 species. -

Ceratophrys Cranwelli) with Implications for Extinct Giant Frogs Scientific Reports, 2017; 7(1):11963-1-11963-10

PUBLISHED VERSION A. Kristopher Lappin, Sean C. Wilcox, David J. Moriarty, Stephanie A.R. Stoeppler, Susan E. Evans, Marc E.H. Jones Bite force in the horned frog (Ceratophrys cranwelli) with implications for extinct giant frogs Scientific Reports, 2017; 7(1):11963-1-11963-10 © The Author(s) 2017 Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Originally published at: http://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-11968-6 PERMISSIONS http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 19th of April 2018 http://hdl.handle.net/2440/110874 www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Bite force in the horned frog (Ceratophrys cranwelli) with implications for extinct giant frogs Received: 27 March 2017 A. Kristopher Lappin1, Sean C. Wilcox1,2, David J. Moriarty1, Stephanie A. R. Stoeppler1, Accepted: 1 September 2017 Susan E.