Kenya VI: Tax Administration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Kenya Gazette

oe RN t_¢ A THE KENYA GAZETTE Published by Authority of the Republic of Kenya (Registered as a Newspaperat the G.P.O.) Vol. CXVITI—No. 132 NAIROBI, 28th October, 2016 Price Sh. 60 CONTENTS GAZETTE NOTICES PAGE PAGE Government Appointments........... .... 4392-4399, 4400 The Physical Planning Act—Completion of Part Development Plan ..........cecccecccseecssecssseessseessseecsseesssesssteesseense 4424 The Births and Death Registration Act—Declaration............ 4399 The Environmental Management and Co-ordination Act— Task Force on the Establishment of Tourism Protection Environmental Impact Assessment Study Repott............ 4424-4426 Service—Appointment 0.0... eeeceeeccecccccssessseessteesstecsseeenee 4400 Disposal of Uncollected Goods....... 4426 Task Force on the Operationalization of the National Loss of Share Certificates ......cc.ccccccecccceecsssesssseesssessseeessessseesseess 4426 Convention Bureauee eecceeccsseecccsseeecnseseecsneeesnsneeecnneees 4400 Lossof Policies 4426-4436 The Land Control Act—Appointment ...0....0..00...cceceeceeeeee 4401-4406 Change of Names 4436-4437 The Land Registration Act—Issue of Provisional Certificates, CC oeeeccecccecccessesssesssessessseessesssessessseessesseeeseeese 4406-4422 The East African Community Customs Management Act, SUPPLEMENTNos. 171 and 172 2004—Appointment and Limits of a Transit Shed, Customs Area, etc—Amendment..... 4422 Legislative Supplement County Governments Notices ..........ccceecceecceccssesesseeeseessteeeseees 4422 LEGAL NOTICE No. The Human Resource Management Professionals -

National Assembly

October 27, 2016 PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES 1 NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OFFICIAL REPORT Thursday, 27th October, 2016 The House met at 2.30 p.m. [The Speaker (Hon. Muturi) in the Chair] PRAYERS COMMUNICATION FROM THE CHAIR MEDIATION COMMITTEE ON ASSISTED REPRODUCTIVE TECHNOLOGY BILL Hon. Speaker: Hon. Members, you may recall that yesterday, Wednesday, 26th October 2016, I conveyed a Message from the Senate regarding its decision on the Assisted Reproductive Technology Bill, National Assembly Bill No.36 of 2014. In the Message, it is noted that the Bill was lost at the Second Reading on 19th October 2016 in the Senate. The effect of this is that the Bill now stands committed to a Mediation Committee in accordance to the provisions of Article 112 of the Constitution. Indeed, the Senate has already nominated five Senators to the aforesaid Mediation Committee. Hon. Members, arising from the above and in consultation with the leadership of the Majority Party and Minority Party in the House, I have appointed the following Members to represent the National Assembly in the Mediation Committee: Hon. Millie Odhiambo Mabona, MP. Hon. John Sakwa, MP. Hon. (Dr.) James Nyikal, MP. Hon. (Ms) Cecilia Ngetich, MP. Hon. (Ms) Florence Kajuju, MP. Hon. Members, the Mediation Committee is advised to expeditiously commence the process of developing an agreed version of the Bill in line with the provisions of Article 113 of the Constitution. Hon. Members, knowing that the House may be proceeding for some short recess, the Committee is encouraged to remember that it has a maximum of 30 days within which to complete its function. -

Experimental Evidence on the Economics of Rural Electrification*

Experimental Evidence on the Economics of Rural Electrification* Kenneth Lee, University of Chicago Edward Miguel, University of California, Berkeley and NBER Catherine Wolfram, University of California, Berkeley and NBER April 2019 ABSTRACT We present results from an experiment that randomized the expansion of electric grid infrastructure in rural Kenya. Electricity distribution is a canonical example of a natural monopoly. Our experimental variation in the number of connections, combined with administrative cost data, reveals considerable scale economies, as hypothesized. Randomized price offers indicate that demand for connections falls sharply with price, and is far lower than anticipated by policymakers. Among newly connected households, average electricity consumption is very low, implying low consumer surplus. Moreover, we do not find meaningful medium-run impacts on economic and non-economic outcomes. We discuss implications for current efforts to increase rural electrification in Kenya, and highlight how credit constraints, bureaucratic red tape, low reliability, leakage, and other factors may affect interpretation of the results. Acknowledgements: This research was supported by the Berkeley Energy and Climate Institute, the Blum Center for Developing Economies, the Center for Effective Global Action, the Development Impact Lab (USAID Cooperative Agreements AID-OAA-A-13-00002 and AIDOAA-A-12-00011, part of the USAID Higher Education Solutions Network), the International Growth Centre, the U.C. Center for Energy and Environmental Economics, the Weiss Family Program Fund for Research in Development Economics, the World Bank DIME i2i Fund, and an anonymous donor. We thank Francis Meyo, Susanna Berkouwer, Victor Bwire, Elisa Cascardi, Corinne Cooper, Stephen Harrell, Eric Hsu, Radhika Kannan, Anna Kasimatis, Tomas Monárrez, Emma Smith, Felipe Vial, and Catherine Wright for excellent research assistance, as well as colleagues at Innovations for Poverty Action Kenya and Remit Kenya. -

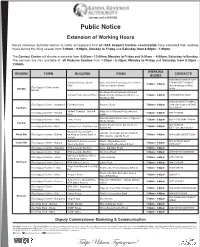

Itax Support Center Working Hours

ISO 9001:2015 CERTIFIED Public Notice Extension of Working Hours Kenya Revenue Authority wishes to notify all taxpayers that all iTAX Support Centres countrywide have extended their working hours during this filing season from 7:00am - 9:00pm, Monday to Friday and Saturday from 8:00pm - 1:00pm. The Contact Centre will also be accessible from 6:00am - 12:00am, Monday to Friday and 9:00am - 4:00pm, Saturday to Sunday. The services are also available at all Huduma Centres from 7:30am - 6:00pm, Monday to Friday and Saturday from 8:00pm - 1:00pm. WORKING REGION TOWN BUILDING ROAD CONTACTS HOURS 0202398534/8897/8470/8 Nairobi Railways Sports Haile Selassie Road adjacent to Uhuru 526/8472/0771628105 7:00am - 9:00pm Club Park, processional way dtdonlinesupport@kra. iTax Support Centre within Nairobi go.ke Nairobi Mombasa Road between Standard Sameer Park - Ground Floor Media Group and General Motors on 7:00am - 9:00pm 391099/0202429081 Mombasa Rd 2312927/30-EXT: 2006 & iTax Support Centre - Mombasa Forodha House Nyerere Road 7:00am - 9:00pm 2118 /2631128/ 2397060/ Southern 077135644/ Malindi Complex - Ground Adjacent to Nakumatt Supermarket, iTax Support Centre - Malindi 7:00am - 9:00pm 042-2130955 Floor Lamu Next Murata Farmers Sacco, Opposite iTax Support Centre - Thika Thika House 7:00am - 9:00pm 067-21705/30812/21834 Hindu Temple Central Kanisa Road ,next to Ibis Hotel, on 061-2030726 iTax Support Centre - Nyeri Premier Plaza Ground Floor 7:00am - 9:00pm Kanisa Rd EXT: 124,106,136,121 Kiptagich House (Same Uganda Road adjacent to Nakumatt -

Kenya V: Laws Governing Taxes and Tax-Like Contributions

Draft version, not yet officially authorized for quoting. James Kanali Kwatemba SJ, MA Kenya V: Laws governing taxes and tax-like contributions With contributions by Dr. Jörg Alt SJ, MA, BD Joerg [Wählen Sie das Datum aus] 1 Draft version, not yet officially authorized for quoting. Inhalt List of Graphics .......................................................................................................................... 4 List of Tables .............................................................................................................................. 4 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 5 1.1 Tax environment .......................................................................................................... 5 1.2 Tax policy and system ................................................................................................. 5 1.3 Long term development strategy and tax policy formulation process ......................... 6 1.4 Stakeholder participation, lobbyism ............................................................................ 8 2 Main tax categories ............................................................................................................ 8 2.1 Definitions ................................................................................................................... 8 2.2 National and County Legislation ................................................................................ -

Provision of Hired Transport Services for Kra Offices Countrywide: Framework Agreement for Two (2) Years

PROVISION OF HIRED TRANSPORT SERVICES FOR KRA OFFICES COUNTRYWIDE: FRAMEWORK AGREEMENT FOR TWO (2) YEARS TENDER NO.KRA/HQS/NCB-071/2018-2019 TIMES TOWER BUILDING P.O. BOX 48240 – 00100 TEL: +254 02 310900 www.kra.go.ke NAIROBI, KENYA. June, 2019 PREBID DATE: 11TH JUNE, 2019 TIME: 10.00 AM CLOSING DATE: 26TH JUNE, 2019 TIME: 11:00 AM Page 1 of 57 Tender Notice 1. The Kenya Revenue Authority invites sealed bids from eligible candidates for the following tenders: ELIGIBILITY PRE- BID - DATE, NO DESCRIPTION CLOSING DATE TIME, AND VENUE AND TIME KRA/HQS/NCB-071/2018-2019: OPEN 11th JUNE, 2019 1. TENDER DOCUMENT FOR PROVISION 26th JUNE, 2019 OF HIRED TRANSPORT SERVICES 10.00. AM 11.00 AM UNDER FRAMEWORK AGREEMENT (TIMES TOWER) 2. Tender documents detailing the requirements of the above tenders in English may be obtained from KRA E-Procurement portal available on the KRA website www.kra.go.ke. Prospective bidders should register for E-Procurement to enable them access the KRA portal under “New Supplier Registration” found under the E - Procurement Tab. 3. Existing KRA suppliers (see list on KRA website) who have not updated their records in SRM System MUST do so Not later than 11th June, 2019 to continue receiving RFxs invitations. For assistance visit any KRA Procurement office countrywide or email: [email protected]. 4. Addenda / clarifications will be posted posted in Kra Website (www.kra.go.ke) and also sent to all prospective tenderes that have registered for the tender in the KRA supplier Portal. 5. -

I EFFECT of CORPORATE GOVERNANCE PRACTICES ON

EFFECT OF CORPORATE GOVERNANCE PRACTICES ON PERFORMANCE OF KENYA FOOTBALL PREMIER LEAGUE PAUL KIPRUTO TUITOEK A Research Project Submitted to School of Business And Economics In Partial Fulfillment of The Requirement For the Award Of Master Of Business Administration of Kabarak University November, 2016 i DECLARATIONAND RECOMMENDATIONS This project report is my original work and to the best of my knowledge, it has not been submitted to any institution or university for examination. PAUL TUITOEK GMB/M/ 0346 /09 /09 Signature ……………………………………………………………Date………………………… Recommendations This project report has been submitted for examination with our recommendation as university supervisors. Dr. Simon Kipchumba School of Business………………………………………..Date………………… Egerton University Dr. Koima Joel School of Computing ………………………………………..Date..………….……. and Bioinformatics Kabarak University ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First and foremost, I would like to thank the almighty God for giving me the strength during the entire compilation of this project. I would like to recognize the tireless efforts by my able lecturer Dr. Simon Kipchumba and Dr. Joel Koima for their invaluable time. I thank sincerely my Dear wife Emily for her unwavering support and love. iii ABSTRACT Football is an “industry” and clubs “businesses” characterized by competition for resources. The opportunities presented by expanding markets and the challenges of an environment characterized by increasing competition require that clubs successfully position themselves to build sustainable, competitive advantage. The main aim of the study was to analyze the effects of corporate governance on performance of soccer management in Kenya Premier League. Particularly the study analyzed; the effect of board composition on performance, board structure on performance, corporate reporting practices on performance of Kenya Football Premier League and to find out the effect of corporate leadership structure on performance of Kenya Football Premier League. -

THE KENYA GAZETTE Published by Authority of the Republic of Kenya (Registered As a Newspaper at the G.P.O.)

SPECIAL ISSUE THE KENYA GAZETTE Published by Authority of the Republic of Kenya (Registered as a Newspaper at the G.P.O.) Vol. CXXI—No. 84 NAIROBI, 28th June, 2019 Price Sh. 60 GAZETTE NOTICE NO. 5861 REPORT OF THE AUDITOR-GENERAL ON THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS OF THE KE NYA REVENUE AUTHORITY FOR THE YEAR ENDED 30TH JUNE, 2018 KEY INFORMATION AND MANAGEMENT (a) Background Information Kenya Revenue Authority (KRA) is a statutory body established by an Act of Parliament, KRA Act Cap 469 of 1995. MISSION - Building Trust through Facilitation so as to foster Compliance with Tax and Customs Legislation. VISION - A globally trusted revenue agency facilitating tax and customs compliance. CORE VALUES § Trustworthy § Ethical § Competent § Helpful (b) Principal Activities The Authority’s objectives are the assessment and collection of revenue, administration, enforcement of laws relating to and accounting for revenue collected under the Act. (c) Key Management The Authority’s day-to-day management is under the following key organs; - Office of the Commissioner General - Domestic Taxes Department - Customs & Border Control Department - Corporate Support Services Department - Investigations and Enforcement Department - Strategy Innovation & Risk Management Department - Legal Service & Board Coordination Department (d) Fiduciary Management The key management personnel who held office during the financial year ended 30th June 2018 and who had direct fiduciary responsibility were: - Commissioner General John K. Njiraini - Domestic Taxes Department Benson Korongo [2405 24062406 THE KENYA GAZETTE 28th June, 2019 - Customs Border Control Department Julius Musyoki - Corporate Support Services Department Ezekiel Saina - Investigations and Enforcement Department David Yego - Strategy, Innovation & Risk Management Department Mohamed Omar - Legal Services & Board Coordination Department Wairimu Nganga - Intelligence & Strategic Operations James Mburu (e) Headquarters Times Tower Building, Haile Selassie Avenue, P.O. -

Chapter 8B1 Judicial Power, Structure, And

CHAPTER 8B1 JUDICIAL POWER, STRUCTURE, AND INDEPENDENT ACCOUNTABILITY IN KENYA AND AFRICA: INTERESTS, FUNCTIONS, PROCESS AND OUTCOMES2 This Chapter may be cited as: Ben Sihanya (forthcoming 2020) “Judicial power, structure, and independent accountability in Kenya and Africa: Interests, process and outcomes,” Part 2, Chapter 8B, in Ben Sihanya (2020) Constitutional Democracy, Regulatory and Administrative in Kenya and Africa Vol. 1: Presidency, Premier, Bureaucracy and Administrative Justice in Kenya, Sihanya Mentoring & Innovative Lawyering, Nairobi & Siaya. 8.15 Commissions and Independent Offices as Quasi-Judicial Tribunals in Kenya and Africa?3 What are Commissions and Independent Offices? Quasi-Judicial tribunals? What are the similarities and differences? What are the merits and demerits as compared to the three arms, branches, or organs of Government? The Semi-Autonomous Governmental Agencies (SAGAs)? Ministries departments and agencies (MDAs)? Constitutional Commissions andIndependent Offices (CCIOs)? What are their relevant quasi-judicial powers and functions...? 8.15.1 Quasi-Judicial Tribunals, Public Enquiry, and Commission of Inquiry in Kenya and Africa Does Kenya still need administrative, quasi-judicial tribunals and commissions of inquiry in light of a restructured judiciary (courts, tribunals, and bodies) as well as the establishment of constitutional4 commissions and independent offices? Are such tribunals still necessary in the light of stricter rules on the establishment of public offices? Significantly, to establish a public office (like tribunals), there should be needs assessment, popular participation, and a recommendation of the Public Service Commission (PSC) (Arts. 1, 10, 47, 132(4),….).5 These also exercise public power. These are now subject to the 2010 Constitution especially with respect to presidential.6 The establishment and the regulation of the conduct and effect of the proceedings of quasi- judicial tribunals are not clearly stipulated under Kenya’s Constitution and public law. -

KRA Customer SATISFACTION SURVEY

CUSTOMER SATISFACTION SURVEY 2017/2018 REPORT Prepared By: SBO Research Ltd Kindaruma Road off Ring Road P.O Box 10567-00400 Nairobi Tel: 020-2145668/2101916/7 Email: [email protected] For: ISO 9001:2015 Certified DECEMBER,2017 Contents 1. CHAPTER ONE: BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 The Organizational Governance and Management ................................................................... 1 1.3 Current Situation at KRA .............................................................................................................. 1 1.4 Research objectives ....................................................................................................................... 3 1.5 Scope of Work ................................................................................................................................. 3 2. CHAPTER TWO: LITERATURE REVIEW ............................................................................................ 4 2.0 Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 4 2.1 Overview of the literature .............................................................................................................. 4 2.2 Customer Satisfaction Theory ..................................................................................................... -

Sandlanders & Supporters Direct

SANDLANDERS & SUPPORTERS DIRECT FIRST AFRICA FOOTBALL REPORT: CLUB STRUCTURES AND LICENSING DURBAN, NOVEMBER 2014 3 Contents Contact Us 1. FOREWORD – LINKING CLUB STRUCTURES AND CLUB LICENSING 4 SANDLANDERS 2. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 5 For further information about Sandlanders, please contact: 3. ABOUT 5 Paul Jones Sandlanders Football 4. PART I - CLUB STRUCTURES 8 1st Floor CAN Mezzanine 49-51 East Road London, N1 6AH 5. PART II - CLUB LICENSING 14 [email protected] 6. PART III - SD CASE STUDY: CLUB LICENSING IN GERMAN FOOTBALL 18 Facebook: facebook/sandlanders.com Twitter: @sandlanders 7. PART IV - COUNTRY CASE STUDIES SUPPORTERS DIRECT 7.1 EGYPT 24 For further information about Supporters Direct, please contact: 7.2 NIGERIA 28 Antonia Hagemann Head of Supporters Direct Europe 7.3 KENYA 32 1st Floor CAN Mezzanine 49-51 East Road London, N1 6AH 7.4 SOUTH AFRICA 36 [email protected] James Mathie 8. PART V - CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 40 SD Club Development Manager 1st Floor CAN Mezzanine 49-51 East Road 9. REFERENCES 42 London, N1 6AH [email protected] SANDLANDERS & SUPPORTERS DIRECT SANDLANDERS & SUPPORTERS DIRECT © FIRST AFRICA REPORT: CLUB STRUCTURES & LICENSING FIRST AFRICA REPORT: CLUB STRUCTURES & LICENSING 4 5 “This report will provide an insight into how African football clubs are Foreword - Linking Club Structures and Licensing currently organised.” are often asked but the answers, despite ABOUT SANDLANDERS NOTE ON METHODOLOGY being crucial to understanding how Sandlanders works with African African football operates, are difficult The four countries featured as case football clubs, supporters’ groups to find. We have therefore provided an studies represent a geographical spread and associations. -

Embodied Performances in Nairobi Underground Hip Hop

Imperfect Resistance: Embodied Performances in Nairobi Underground Hip Hop DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By RaShelle Ranae Peck, M.A. Graduate Program in Comparative Studies The Ohio State University 2014 Dissertation Committee: Barry Shank, Advisor Nina Berman Maurice Stevens Copyright by RaShelle Ranae Peck 2014 Abstract My dissertation project, Imperfect Resistance: Embodied Performances in Nairobi Underground Hip Hop, explores how hip hop practitioners in Kenya enact agentive subjectivity through the creative maneuverability of bodily performances. Non- commercial rappers operate from a post-Mau Mau underground cultural aesthetic of resistance, which harnesses the long trajectories of narrativized political struggles and underground hip hop culture to challenge categories of difference and circumvent disciplinary regimes that encode bodies. Underground performances materialize out of long trajectories of the performative practices of Congolese dance, US rap, dancehall, and Kenyan Benga, which include the knotty transnational history of the black body as propertied and commodified. Hip hop gestures and stances contest an environment where state repression, a restrictive music industry, and the struggle for economic security all work to create constraining conditions for many practitioners. These embodied enactments are heavily masculinized, and male and female artists use this embodied knowledge to both celebrate and challenge hip hop’s gendered spaces. Artists develop creative gestures and movements that are in conversation with both larger historic, cultural, and economic realities, as well as their racial, national, and gender subjectivities. Rappers create music videos, which espouse their subjectivities as artists and allow them to participate in a global rap culture.