Daily Life in New France

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State of Wisconsin

CONSTITUTION 0F THE STATE OF WISCONSIN. ADOPTED IN CONVENTION, AT xVIADISON, ON THE FIRST DAY OF FEBRUARY, IN THE YEAR OF OUR LORD ONE THOUSAND EIGHT HUN DRED AND FORTY-EIGHT. PREAMBLE. We, the people of Wisconsin, grateful to Almighty God fbr oar freedom, in order to secure its blessings, form a more perfect gorer:; • menu insure domestic tranquility, and promote the general weifars ; do establish this CONSTITUTION. ARTICLE I. DECLARATION OF RIGHTS. SECTION I. All men are born equally free and indepandent, ar;d have certain inherent rights, among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness ; to secure these rights, governments are insti tuted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of tha governed; SEC. 2. There shall be Heither slavery nor involuntary servitude m this State otherwise than for the punishment of crime, whereof the party shall have been duly convicted. SEC. 3. Every pjrson may freely speak, write and pubh'sh his sentiments on all subjects, being responsible for the abuse of that right, and no laws shall be passed to restrain or abridge the liberty of speech or of the press. In all criminal prosecutions or indictmentii for libel, the truth may be given in evidence, and if it shall appear to the jury, that the matter charged as libellous, be true, and was published with good motives, and for justifiable ends, the party shaii be acquitted ; and the jury shall have the right to determine the law and the fact. SEC. 4. The right of the people peaceably to assembly to consul': for the common good, and to petition the Government or any depa/t ment thereof, shall never be abridged. -

Living and Learning in New France, 1608-1760

CJSAEIRCEEA 23) Novemberlnovembre 2010 55 Perspectives "A COUNTRY AT THE END OF THE WORLD": LIVING AND LEARNING IN NEW FRANCE, 1608-1760 Michael R. Welton Abstract This perspectives essay sketches how men and women of New France in the 17th and 18th centuries learned to make a living , live their lives, and express themselves under exceptionally difficult circumstances. This paper works with secondary sources, but brings new questions to old data. Among other things, the author explores how citizen learning was forbidden in 17th- and 18th-century New France, and at what historical point a critical adult education emerged. The author's narrative frame and interpretation of the sources constitute one of many legitimate forms of historical inquiry. Resume Ce croquis d'essai perspective comment les hommes et les femmes de la Nouvelle-France au XVlIe et XV1I1e siecles ont appris a gagner leur vie, leur vie et s'exprimer dans des circonstances difficiles exceptionnellement. Cette usine papier avec secondaire sources, mais apporte de nouvelles questions d'anciennes donnees. Entre autres choses, I' auteur explore comment citoyen d' apprentissage a ete interdite en Nouvelle-France XVlIe-XV1I1e siecle et a quel moment historique une critique de ['education des adultes est apparu. Trame narrative de ['auteur et ['interpretation des sources constituent une des nombreuses formes legitimes d'enquete historique. The Canadian Journal for the Study of Adult Education/ La Revue canadienne pour i'ill/de de i'iducation des adultes 23,1 Novemberlnovembre 2010 55-71 ISSN 0835-4944 © Canadian Association for the Study of Adult Education! L' Association canadienne pour l' etude de I' education des adultes 56 Welton, ({Living and Learning in New France, 1608-1760" Introduction In the 1680s one intendant wrote that Canada has always been regarded as a country at the end of the world, and as a [place of] exile that might almost pass for a sentence of civil death, and also as a refuge sought only by numerous wretches until now to escape from [the consequences of] their crimes. -

Chapman's Bookstore 2407 St

'. , ~ ~- - - ---rom-: iii ,~-----.--- AMERICAN LIBRARY ASSOCIATION Montreal Conference AT McGILL UNIVERSITY JUNE 6 TO I2, I900 Programnle and Guide ISSUED BY THE LOCAL COMMITTEE MONTREAL THE HERALD PRESS eont~nts History of Montreal Description McGill University Montreal Libraries Sunday Services Summary of Points of Interest in and about Montreal Programme of Local Elltertainment Local Committee Wheelmen's Favorite Routes Map of Montreal Advertisers Published for the I,oca\ Committee By F. E. PHELAN, 2331 St. Catherine Street, lVIontreal HISTORY HE history of Montreal as a centre of population commences with the visit of Jacques Cartier to the Indians of the town of Hochelaga in 1535. The place was situated close to T Mount Royal, on a site a short distance from the front of the McGill College Grounds, and all within less than a block below Sherbrooke Street, at Mansfie1.d Street. It was a circular palisaded Huron-Iroquois strong hold, which had been in existence for seyeral generations and had been founded by a party which had broken off in some manner from the Huron nations at Lake Huron, at a period estimated to be somewhere about 1400. It was at that time the dominant town of the entire Lower St. Lawrence Valley, and apparently also of Lake Champlain, in both of which quarters numerous settlements of the same race had sprung from it as a centre. Cartier describes how he found it in the following words: " And in the midst of those fields is situated and fixed the said town of Hochelaga, near and joining a mountain which is in its neighbour hood, well tilled and exceedingly fertile; therefrom one sees very far. -

Women of New France

Women of New France Introducing New France Today it may be hard to imagine that vast regions of the North American continent were once claimed, and effectively controlled, by France. By 1763 some 70,000 French speakers based primarily in what is now the province of Quebec, managed to keep well over 1,000,000 British subjects confined to the Atlantic seaboard from Maine to Florida. France claimed land that included 15 current states, including all of Michigan. The early history of North America is a story of struggle for control of land and resources by Women in New France French settlers in Nouvelle France (New France in English), English settlers We know very little about the everyday lives of people in what in the Thirteen Colonies, and Native peoples who already lived in the areas was New France, particularly the women. Native women, from a that became the US and Canada. wide range of nations along the St. Lawrence and Great Lakes river system, had lived in North America for thousands of years before the arrival of French explorers. While there was a good deal of variety among Indian societies, most Native women lived more independent lives than did their European counterparts. In some societies, in addition to the usual child-rearing and household economy practices, Native women had real political power and could elect village and tribal leaders. New France 1719 European Women’s Roles European women’s lives, like those of their Native American counterparts, were shaped by the legal, cultural, and religious values of their society. -

New France from 1713-1800 by Adam Grydzan and Rebecca

8 Lessons Assignment Adam Grydzan & Rebecca Millar Class: CURR 335 For: Dr. Christou Lesson 1: Introduction Overview: This lesson is the introductory lesson in which we will overview the parties involved in “Canada” at the time exp: New France, Britian, First Nations. In addition, we will begin to explore the challenges facing individuals and groups in Canada between 1713 and 1800 and the ways in which people responded to those challenges. It will involve youtube clips showing an overview of where Canada was at the time and involve students using critical thinking skills to understand how the various parties felt during the time. Learning Goal: Critical thinking skills understanding the challenges people faced between 1713 and 1800 as well as knowledge of the structure of Canada in 1713 and the relationship between France, Britian and the First Nations during this time. Curriculum Expectations: 1. A1.2 analyze some of the main challenges facing individuals and/or groups in Canada between 1713 and 1800 and ways in which people responded to those challenges, and assess similarities and differences between some of these challenges and responses and those of present-day Canadians 2. Historical perspective Materials: Youtube Videos: Appendix A1: Video - A Part of our Heritage Canada https://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=O1jG58nghRo Appendix A2 Video – A Brief History of Canada https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ksYSCWpFKBo Textbook: Appendix A3 Textbook – Pearson History Grade 7 http://kilby.sac.on.ca/faculty/nMcNair/7%20HIS%20Documents/His7_Unit1.pdf Plan of Instruction: Introduction (10 minutes): The lesson will begin with playing the two videos that introduce the ideas of security and events and perspectives leading up to the final years of New France. -

The French Frontier of Settlement in Louisiana : Some Observations on Cultural Change in Mamou Prairie Gerald L

Document generated on 09/30/2021 10:28 a.m. Cahiers de géographie du Québec The French Frontier of Settlement in Louisiana : Some Observations on Cultural Change in Mamou Prairie Gerald L. Gold Le Québec et l’Amérique française : 2- La Louisiane Article abstract Volume 23, Number 59, 1979 Changes in Cajun culture of the Southwestem Prairies of Louisiana can best be explained through the ethnohistorical study of pre-1952 cotton sharecropping URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/021437ar communities, and the subsequent displacement of the tenant farmers to DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/021437ar service centres. Isolation of the sharecroppers was culturally-reinforced by a strong egalitarian ideology. From this milieu, Cajun music emerged as a See table of contents marker of an indigenous Louisiana francophone society. The decline of cotton cultivation reversed the demographic balance between countryside and village and favoured the emergence of merchant and service strata composed of former farmers. The new bourgeoisie sought means of cultural revival through Publisher(s) the reinterpretation of rural culture in a town context. Using radio, Département de géographie de l'Université Laval newspapers and the strong external support of folk "purists" they selectively cultivated ethnic differences. French was strengthened in a public context even though it continued to decline in private and familial contexts. ISSN The response to this transformation differs among occupation groups. Retired 0007-9766 (print) sharecroppers in Mamou, the most "Cajun" in their everyday retention of 1708-8968 (digital) "traditional" social and linguistic behaviour, are the least likely to advocate the survival of that culture and its transmission to another generation. -

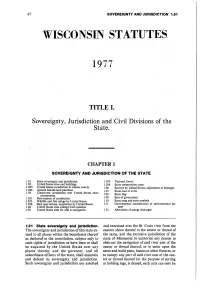

1977 Chapter 1

67 SOVEREIGNTY AND JURISDICTION 1 .01 WISCONSIN STATUTES 1977, TITLE I. Sovereignty, Jurisdiction and Civil Divisions of the State . CHAPTER 1 SOVEREIGNTY AND JURISDICTION OF THE STATE 1 01 State sovereignty and jurisdiction 1,055 Nationa l fores t . United States sites and buildings . 1.. .056 State conservation areas . 1 025- United States jurisdiction in Adams county , 1 .06 Surveys by United States ; adjustment of damages , . 1 026 . Apostle Islands land purchase . 1 07 State coat of arms : 1 03 Concurrent jurisdiction over. United States sites conveyances .: ; 1 .08 State flag ,g 1 031 Retr oces sion of jurisdiction 1 09 Seat of government 1 035 Wildlife a nd fish refuge by United States . 1 10 State song and state symb ols:, 1 .0.36 . Bi rd reser vations, acquisition by United States . 1 ll Governmental consideration of environmen tal im- 1 04 United States sites exempt from taxationn pact. 105 United States sites for aids to navigation 1 12 Alleviation of' energy shor ta ges 1.07. State sovereignty and jurisdiction . a nd exercised over the St.' C roix river from the The sovereignty and jurisdiction of th is sta te ex- eastern shore th ereof' to the center or t hread of tend to all pl aces within the bound aries thereof the same, and the exclusive jurisdiction of the as declared in the constitu tion, s ubject only to state of Minnesota to auth or ize any perso n to such rights of j urisdiction as have been or s hall obstruct the navigation of" said. river east of the be acquired by the United States over any cente r or thread thereof, -

Turcotte History of the Ile D'orleans English Translation

Salem State University Digital Commons at Salem State University French-Canadian Heritage Collection Archives and Special Collections 2019 History of the Ile d'Orleans L. P. Turcotte Elizabeth Blood Salem State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.salemstate.edu/fchc Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Turcotte, L. P. and Blood, Elizabeth, "History of the Ile d'Orleans" (2019). French-Canadian Heritage Collection. 2. https://digitalcommons.salemstate.edu/fchc/2 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives and Special Collections at Digital Commons at Salem State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in French-Canadian Heritage Collection by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons at Salem State University. History of the Ile d’Orléans by L.P. Turcotte Originally published in Québec: Atelier Typographique du “Canadien,” 21 rue de la Montagne, Basse-Ville, Québec City 1867 Translated into English by Dr. Elizabeth Blood, Salem State University, Salem, Massachusetts 2019 1 | © 2019 Elizabeth Blood TRANSLATOR’S PREFACE It is estimated that, today, there are about 20 million North American descendants of the relatively small number of French immigrants who braved the voyage across the Atlantic to settle the colony of New France in the 17th and early 18th centuries. In fact, Louis-Philippe Turcotte tells us that there were fewer than 5,000 inhabitants in all of New France in 1667, but that number increased exponentially with new arrivals and with each new generation of French Canadiens. By the mid-19th century, the land could no longer support the population, and the push and pull of political and economic forces led to a massive emigration of French-Canadians into the United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. -

Changes in Freshwater Mussel Populations of the Ohio River: 1,000 BP to Recent Times1

Changes in Freshwater Mussel Populations of the Ohio River: 1,000 BP to Recent Times1 RALPH W. TAYLOR, Department of Biological Sciences, Marshall University, Huntington, WV 25701 ABSTRACT. Through the use of literature records and new data, it was possible to compile a list of species of freshwater mussels that inhabited the upper Ohio River (Ohio River Mile [ORM] 0-300) around a thou- sand years ago. This information was derived from specimens found associated with Indian middens lo- cated along the banks of the Ohio. Analysis of these data indicates that at least 31 species of mussels were present in the river. Arnold Ort- mann recorded 37 species from the same area as a result of his many years of collecting around the turn of the 20th century. Thirty-three species have been collectively documented as currently residing in limited numbers in the river. The number of species present has remained essentially unchanged through time. There have been, however, significant changes in species composition and total numbers of individual mus- sels present. Occasionally, healthy populations can be found presently but much of the upper Ohio River is devoid of mussel life. Several large-river species have become established in this reach of the river as a con- sequence of damming and the resulting increase in depth, greater siltation and slowed rate of flow. Seven- teen species known to have previously inhabited the upper Ohio River are listed as presumed to no longer survive there. OHIO J. SCI. 89 (5): 188-191, 1989 INTRODUCTION and Dam in 1976, coupled with the current expansion For thousands of years, the Ohio River flowed freely of Gallipolis Locks and Dam, it appears that the present for nearly 1,000 mi — from its origin at the junction of series of high-rise dams (12 ft [3 m] navigation channel) the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers to its conflu- will meet the barge traffic needs well into the 21st cen- ence with the Mississippi River. -

William Henry Drummond's Habitants and the Quebec of My Youth

John Lepage William Henry Drummond’s Habitants and the Quebec of My Youth WAS BROWSING AMONG THE mildewed fare at Voltaire and Rous- I seau, purveyors of fine second-hand books, in Glasgow some years ago when I came across a rarity not likely to be appreciated by Scottish readers: The Habitant, And Other French-Canadian Poems, by William Henry Drum- mond, published by G.B. Putnam’s Sons, New York and London, 1897. Drummond (1854–1907) was an Irish immigrant to Canada, who received an MD from Bishop’s College in 1883 and practised medicine in Montreal and the Eastern Townships. He was made a fellow of the Royal Society of Canada in 1899 and received honorary degrees from the University of Toronto and Bishop’s College. The Habitant was the first of five books of verse produced by Drummond, including Phil-o-Rum’s Canoe (1898), John- nie Courteau (1901), The Voyageur(1905), and The Great Fight (1908). The ballad was in fashion at the time, and Drummond wrote ballads in heavily accented dialect English, mingled with colloquial French, on the character of rural life in Quebec. As I had not heard mention of Drummond in twenty-five years or more, the volume reached out to me like a fond remembrance of things past. In fact, it was a reminiscence of my childhood, and my lips curled into a parody of Jean Chrétien from a time of my life before I had heard of Jean Chrétien, as I reverently intoned, “On wan dark night on Lac St. Pierre, / De win’ she blow, blow, blow.” There was hardly a moment of hesitation on my part, and not a flicker of shame.O n the contrary, I wondered innocently what had become of this friend of my youth. -

Grand Portage As a Trading Post: Patterns of Trade at "The Great Carrying Place"

Grand Portage as a Trading Post: Patterns of Trade at “the Great Carrying Place” By Bruce M. White Turnstone Historical Research St. Paul, Minnesota Grand Portage National Monument National Park Service Grand Marais, Minnesota September 2005 On the cover: a page from an agreement signed between the North West Company and the Grand Portage area Ojibwe band leaders in 1798. This agreement is the first known documentary source in which multiple Grand Portage band leaders are identified. It is the earliest known documentation that they agreed to anything with a non-Native entity. Contents List of Tables ..................................................................................................................... ii List of Illustrations ............................................................................................................. ii Preface ............................................................................................................................... iii Introduction .........................................................................................................................1 Trade Patterns .....................................................................................................................5 The Invention of the Great Lakes Fur Trade ....................................................................13 Ceremonies of Trade, Trade of Ceremonies .....................................................................19 The Wintering Trade .........................................................................................................27 -

Economic Status and Reproductive Success in New France

ECONOMIC STATUS AND REPRODUCTIVE SUCCESS IN NEW FRANCE Gregory Clark, University of California, Davis and Gillian Hamilton, University of Toronto. Early Draft. Introduction It is often reported that at least in developing countries “fertility typically falls with education”1 Recently, macroeconomists in particular have taken note of this stylized fact and posited a relationship between this fertility gap and inequality and growth. For example, Kremer and Chen (1999 and 2000) illustrate that this type of fertility differential may compound inequality, assuming that the uneducated are less likely to invest in their children’s education. The uneducated population will grow more quickly than the educated and as a result the wage of the unskilled will fall. Because the opportunity cost of children falls for the uneducated, they have even more children. Hence the degree of inequality rises.2 Consistent with their model, they note that empirical evidence indicates that the fertility gap between the educated and uneducated is larger in countries with higher degrees of inequality.3 Dahan and Tsiddon (1998) have a similar approach but focus on the demographic transition. In their model, they also assume that the uneducated will have more children than the educated and the educated will be more likely to educate their children. As a result, the uneducated population experiences relatively rapid growth (hence a rising fertility rate overall and growing income inequality—the first phase of the demographic transition). This will eventually increase the return to skill, causing some unskilled to educate their children. This transition will lead to lower overall fertility rate (as more young are educated and 1 Kremer and Chen (1999: 155).