Paradigm Shift in Evangelism. a Study of the Need for Contextualization in the Mission of Southern Baptists

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Declaration Signatories

DECLARATION SIGNATORIES HEADS OF PARTNER ORGANIZATIONS MOST REV. FRANK J. DEWANE BISHOP OF VENICE & CHAIRMAN, COMMITTEE ON JAMES ACKERMAN DOMESTIC JUSTICE & HUMAN DEVELOPMENT PRESIDENT & CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER United States Conference of Catholic Bishops Prison Fellowship Ministries (Lansdowne, VA) DHARIUS DANIELS DR. LEITH ANDERSON SENIOR PASTOR PRESIDENT Kingdom Church (Ewing, NJ) National Association of Evangelicals (Washington, DC) DR. JOSHUA DARA SR. DR. RUSSELL MOORE PASTOR PRESIDENT Zion Hill Baptist Church (Pineville, LA) Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission of the Southern Baptist Convention (Washington, DC) REV. CANON DR. ALLISON DEFOOR CANON TO THE ORDINARY JOHN STONESTREET Episcopal Diocese of Florida (Jacksonville, FL) PRESIDENT The Colson Center for Christian Worldview REV. DR. SCOTT N. FIELD (Colorado Springs, CO) SENIOR PASTOR First United Methodist Church (Crystal Lake, IL) DR. JIM GARLOW JUSTICE DECLARATION PROJECT WRITER SENIOR PASTOR DR. C. BEN MITCHELL Skyline Wesleyan Church (San Diego, CA) PROVOST, VICE PRESIDENT FOR ACADEMIC AFFAIRS, & GRAVES PROFESSOR OF MORAL PHILOSOPHY DAVID R. HELM Union University (Jackson, TN) LEAD PASTOR Holy Trinity Church of Hyde Park (Chicago, IL) HEADS OF CHRISTIAN DENOMINATIONS, BISHOP GARLAND R. HUNT ESQ. SENIOR PASTOR CLERGY & PASTORS The Father’s House (Norcross, GA) THE MOST REV. DR. FOLEY BEACH ARCHBISHOP AND PRIMATE DR. JOEL C. HUNTER Anglican Church in North America (Loganville, GA) SENIOR PASTOR Northland – A Church Distributed (Longwood, FL) CHRISTOPHER BROOKS PASTOR Evangel Ministries (Detroit, MI) HARRY R. JACKSON, JR. PRESIDING BISHOP OF INTERNATIONAL COMMUNION OF EVANGELICAL CHURCHES DAVID E. CROSBY Senior Pastor of Hope Christian Church (Beltsville, MD) SENIOR PASTOR First Baptist New Orleans (New Orleans, LA) JOHN JENKINS THE MOST REV. -

James P. Eckman, Ph.D

———————————————— THINK AGAIN EXPLORING CHURCH STUDY NOTES L HISTORY ———————————————— ———————————————— James P. Eckman, Ph.D. PERSONA 1 LIVING WORD AMI CHURCH HISTORY ———————————————— ———————————————— CONTENTS THINK AGAIN Introduction 1 Foundation of the Church: The Apostolic Age 2 The Apostolic Fathers L STUDY NOTES STUDY NOTES L 3 Defending the Faith: Enemies Within and Without 4 The Ancient Church and Theology 5 The Medieval Church 6 The Reformation Church 7 The Catholic Church Responds 8 The Church and the Scientific Revolution 9 The Church, the Enlightenment, and Theological Liberalism 10 The Church and Modern Missions 11 The Church and Revivals in America 12 The Church and Modernity Glossary Bibliography1 PERSONA 1 Eckman, J. P. (2002). Exploring church history (5). Wheaton, Ill.: Crossway. 2 LIVING WORD AMI CHURCH HISTORY ———————————————— ———————————————— INTRODUCTION THINK AGAIN In general most Christians are abysmally ignorant of their Christian heritage. Yet an awareness of the history of God’s church can help us serve the Lord more effectively. First, knowledge of church history brings a sense of perspective. Many of the cultural and doctrinal battles currently being STUDY NOTES L fought are not really that new. We can gain much from studying the past. Second, church history gives an accurate understanding of the complexities and richness of Christianity. As we realize this diversity and the contributions many individuals and groups have made to the church, it produces a tolerance and appreciation of groups with which we may personally disagree. Finally, church history reinforces the Christian conviction that the church will triumph! Jesus’ words, “I will build My church,” take on a richer meaning. -

A Rationale for an Independent Baptist Church to Clarify Its Mission, Analyze Its Program, Prioritize Its Objectives and Revitalize Its Ministry

LIBERTY BAPTIST THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY A RATIONALE FOR AN INDEPENDENT BAPTIST CHURCH TO CLARIFY ITS MISSION, ANALYZE ITS PROGRAM, PRIORITIZE ITS OBJECTIVES AND REVITALIZE ITS MINISTRY A Thesis Project Submitted to Liberty Baptist Theological Seminary in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOcrOR OF MINISTRY By Richard T. Carns Lynchburg, Virginia March, 1993 LIBERTY BAPTIST THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY THESIS PROJECT APPROVAL SHEET 11 ABSTRACT A RATIONALE FOR AN INDEPENDENT BAPTIST CHURCH TO CLARIFY ITS MISSION, ANALYZE ITS PROGRAM, PRIORITIZE ITS OBJECTIVES AND REVITALIZE ITS MINISTRY Richard T. Carns Liberty Baptist Theological Seminary, 1993 Mentor: Dr. William Matheny Reader: Dr. James Freerksen The purpose of this thesis project is to provide a rationale for the pastor of an independent Baptist church to lead his church into a revitalization program. The author selected the topic for two reasons: (1) Church stagnation/decline has become a spiritual disease of epidemic proportions and (2) The author pastored a church which was experiencing decline and viable strategies needed to be understood, accepted and implemented. The main body presents the reasons a church needs to clarify its mission, analyze its program, prioritize its objectives and revitalize its ministry. The appendices delineate the steps taken in the author's church to pursue the above objectives. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES .............................................VI INTRODUCTION ..............................................1 Chapter 1. "WHY ARE WE HERE?" CLARIFYING TI-IE MISSION .........................7 The Local Church as God's Design The Local Church Having a Distinct Purpose The Local Church Identifying Its Purpose Through a Mission Statement 2. "HOW ARE WE DOING?" ANALYZING THE PROGRAM ........................ -

"Strength for the Journey": Feminist Theology and Baptist Women Pastors

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2014 "Strength for the Journey": Feminist Theology and Baptist Women Pastors Judith Anne Bledsoe Bailey College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the History of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Bailey, Judith Anne Bledsoe, ""Strength for the Journey": Feminist Theology and Baptist Women Pastors" (2014). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623641. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-0mtf-st17 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Strength for the Journey”: Feminist Theology and Baptist Women Pastors Judith Anne Bledsoe Bailey Richmond, Virginia Master of Arts, The College of William and Mary, 2000 Master of Religious Education, Union Theological Seminary, NY, 1966 Bachelor of Arts, Lambuth College, 1964 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy American Studies Program The College of William and Mary May 2014 © Copyright by Judith Anne Bledsoe Bailey, 2014 All Rights Reserved APPROVAL -

The Future of Southern Baptists: Biblical Mandates for What We

1 The Future Of Southern Baptists: Mandates For What We Should Be In The 21st Century Southern Baptists have a colorful and fascinating history by any standard of measure. From the Convention’s humble beginnings in Augusta, Georgia on May 8, 1845 (only 293 persons attended the Inaugural Convention and 273 came from 3 states: Georgia, South Carolina and Virginia),1 the Convention’s 2004 Annual could boast of 40 State Conventions, 1,194 Associations, 43,024 Churches and a Total Membership of 16,315,050. There were 377,357 Baptisms, and other additions totaled 422,350. Cooperative Program Giving for 2002-2003 was $183,201,694.14, and Total Receipts recorded was $9,648,530,640.2 This is quite impressive any way you look at it, and for all of this and more Southern Baptists give thanks and glory to God. We are grateful to our Lord for what He has done for us and through us. However, it is to the future that we must now look. In spite of periodic blips on the cultural and moral screen, our nation grows more secular and our world more hostile to “the faith once for all delivered to the saints” (Jude 3). Southern Baptists, in the midst of the swirling tides of modernity, have attempted to stake their claim and send a clear message on who we are. The Conservative Resurgence initiated in 1979 charted the course, and I would argue the Baptist Faith and Message 2000 was something of a defining moment.3 Still, I am not convinced we have a clear 1 Leon McBeth, The Baptist Heritage (Nashville: Broadman, 1987), 388. -

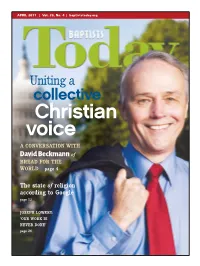

BT April11 Nat V4:2011 Baptists Today 3/15/11 4:19 PM Page 1

BT_April11_Nat_v4:2011 Baptists Today 3/15/11 4:19 PM Page 1 APRIL 2011 | Vol. 29, No. 4 | baptiststoday.org Uniting a collective Christian voice A CONVERSATION WITH David Beckmann of BREAD FOR THE WORLD page 4 The state of religion according to Google page 13 JOSEPH LOWERY: ‘OUR WORK IS NEVER DONE’ page 26 BT_April11_Nat_v4:2011 Baptists Today 3/15/11 4:19 PM Page 2 BT_April11_Nat_v4:2011 Baptists Today 3/15/11 4:19 PM Page 3 John D. Pierce BAPTISTS TODAY APRIL 2011 | Vol. 29 No. 4 Executive Editor [email protected] Jackie B. Riley “To serve churches by providing a reliable source of unrestricted news coverage, thoughtful analysis, Managing Editor helpful resources and inspiring features focusing on issues of importance to Baptist Christians.” [email protected] Julie Steele Chief Operations Officer [email protected] PERSPECTIVES Tony W. Cartledge Contributing Editor > A better way than escalating the politics of marriage ..............9 [email protected] By John Pierce Bruce T. Gourley An autonomous national Online Editor [email protected] > Godsey’s new book focused on moral quality ........................14 Baptist news journal By Fisher Humphreys Vickie Frayne Art Director Jannie Lister Constructive approaches Office Assistant IN THE NEWS Bob Freeman, Kim Hovis to calling a minister > National debt new hot issue for evangelicals..........................12 Marketing/Development Associates By Jack Causey Walker Knight Jack U. Harwell Publisher Emeritus Editor Emeritus > The state of religion according to Google ..............................13 10 Board of Directors By Bruce Gourley Gary F. Eubanks, Marietta, Ga. (chairman) Kelly L. Belcher, Spartanburg, S.C. > Georgia pastor Bill Self announces succession ......................23 (vice chair) Reflections on the first plan to congregation Z. -

The Southern Baptist Convention “Crisis” in Context: Southern Baptist Conservatism and the Rise of the Religious Right

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Masters Theses & Specialist Projects Graduate School Spring 2017 The outheS rn Baptist Convention “Crisis” in Context: Southern Baptist Conservatism and the Rise of the Religious Right Austin R. Biggs Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses Part of the Christianity Commons, Cultural History Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the New Religious Movements Commons Recommended Citation Biggs, Austin R., "The outheS rn Baptist Convention “Crisis” in Context: Southern Baptist Conservatism and the Rise of the Religious Right" (2017). Masters Theses & Specialist Projects. Paper 1967. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses/1967 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses & Specialist Projects by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE SOUTHERN BAPTIST CONVENTION “CRISIS” IN CONTEXT: SOUTHERN BAPTIST CONSERVATISM AND THE RISE OF THE RELIGIOUS RIGHT A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History Western Kentucky University Bowling Green, Kentucky In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts By Austin R. Biggs May 2017 THE SOUTHERN BAPTIST CONVENTION “CRISIS” IN CONTEXT: SOUTHERN BAPTIST CONSERVATISM AND THE RISE OF THE RELIGIOUS RIGHT Dean, Graduate School Date ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are several people who, without their assistance and support, this project would not have been possible. I would first like to thank my thesis committee. I would like to thank my committee chair, Dr. Tamara Van Dyken. It was in her History of Religion in America course that I stumbled across this topic and she has provided me with vital guidance and support from the very beginning. -

Anabaptism: the Beginning of a New Monasticism

[A paper given at “Christian Mission in the Public Square”, a conference of the Australian Association for Mission Studies (AAMS) and the Public and Contextual Theology Research Centre of Charles Sturt University, held at the Australian Centre for Christianity and Culture (ACC&C) in Canberra from 2 to 5 October 2008.] Anabaptism: The Beginning of a New Monasticism by Mark S. Hurst Introduction Wolfgang Capito, a Reformer in Strasbourg, wrote a letter to the Burgermeister and Council at Horb in May 1527 warning about the Anabaptist leader Michael Sattler. He was worried that Sattler was bringing about “the beginning of a new monasticism.” (Yoder, 87) Both Anabaptism and “new monasticism” are being explored today as relevant expressions of the Christian faith in our post-Christendom environment. The connections between these two movements will be examined in a conference sponsored by the Anabaptist Association of Australia and New Zealand in January 2009 as they were in a recent conference in Great Britain called “New Habits for a New Era? Exploring New Monasticism,” co-sponsored by the British Anabaptist Network and the Northumbria Community. (See http://www.anabaptistnetwork.com/node/19 for papers from the conference.) The British gathering raised a number of questions for these movements: “We hear many stories of ‘emerging churches’ and ‘fresh expressions of church’, but Christians in many places are also rediscovering older forms of spirituality and discipleship. Some are drawing on the monastic traditions to find resources for a post- Christendom culture. ‘New monasticism’ is the term many are using to describe these attempts to re-work old rhythms, rules of life and liturgical resources in a new era. -

Wednesday Morningjune 16, 2021

2021 ANNUAL MEETING OF THE SOUTHERN BAPTIST CONVENTION DAILY BULLETIN 97TH VOLUME | MUSIC CITY CENTER, NASHVILLE, TENNESSEE | JUNE 15–16, 2021 ORDER OF BUSINESS WEDNESDAY MORNING JUNE 16, 2021 8:00 Worship // Branden Williams, Convention music director; worship pastor, The Summit Church, Durham, North Carolina REPORT OF THE TUESDAY PROCEEDINGS 8:15 Prayer // Sarah Farley, student mobilization associate, OF THE SBC ANNUAL MEETING International Mission Board, Richmond, Virginia TUESDAY, JUNE 15, 2021 8:20 Send Relief TUESDAY MORNING, JUNE 15, 2021 8:30 Committee on Order of Business Report (Third) // 1. Branden Williams (NC), Convention music director; worship Adam W. Greenway, chair; president, The Southwestern leader, The Summit Church, Durham, led congregational praise Baptist Theological Seminary, Fort Worth, Texas and worship. 8:40 Previously Scheduled Business 2. Randy Davis (TN), executive director-treasurer, Tennessee Baptist Mission Board welcomed the messengers and led in 8:50 Committee on Committees Report // Meredith Cook, prayer for the Convention and president J. D. Greear (NC). chair, Neartown Church, Houston, Texas 3. President J. D. Greear (NC) announced he would be using the 9:00 Committee on Nominations Report // Andrew Hopper, Judson Gavel, while presiding the Annual Meeting. Greear chair; lead pastor, Mercy Hill Church, Greensboro, called to order the one hundred sixty-third session of the North Carolina Southern Baptist Convention in the one hundred seventy- sixth year of its history at 8:29 a.m. in the Music City Center, 9:15 Joint Seminary Reports // Nashville, Tennessee. Jeff Iorg, president, Gateway Seminary of the Southern 4. President Greear (NC) welcomed messengers and introduced Baptist Convention, Ontario, California; the chief parliamentarian, Barry McCarty (GA), along with Jason K. -

Evangelicals and DACA PRESS RELEASES

Evangelicals and DACA PRESS RELEASES: EVANGELICALS’ SUPPORT FOR DREAMERS HIGHLIGHTS URGENT NEED FOR ACTION Dec. 1, 2017 EVANGELICAL LEADERS CALL FOR LEGAL PATH FOR DREAMERS Nov. 29, 2017 FAITH, LAW ENFORCEMENT, BUSINESS LEADERS CALL FOR DREAMER LEGISLATION Sept. 13, 2017 LOCAL LEADERS TARGET CONGRESS FOLLOWING DACA RESCISSION Sept. 6, 2017 DREAM ACT DRAWS BIPARTISAN SUPPORT AROUND THE COUNTRY July 21, 2017 MEDIA HITS AND OP-EDS: BAPTIST PRESS: Time ticking to protect Dreamers, Baptists tell media By Tom Strode Dec. 1, 2017 http://bpnews.net/50000/time-ticking-to-protect-dreamers-baptists-tell-media CHRISTIAN POST (Liz Dong Op-Ed): Dreamers Are Thankful By Liz Dong Nov. 22, 2017 https://www.christianpost.com/voice/dreamers-are-thankful.html CBN NEWS: Evangelical Leaders Call for Congress to Act on Behalf of Dreamers By Caitlin Burke Oct. 6, 2017 http://www1.cbn.com/cbnnews/politics/2017/october/evangelical-leaders-call-for-congress-to- act-on-behalf-of-dreamers BAPTIST PRESS: Evangelical leaders call for help for Dreamers By Tom Strode Oct. 5, 2017 http://www.bpnews.net/49670/evangelical-leaders-call-for-help-for-dreamers CHRISTIAN POST: Evangelical, Latino Leaders Urge Trump, Congress Not to Punish Dreamers With Deportations By Stoyan Zaimov Oct. 6, 2017 http://www.christianpost.com/news/evangelical-latino-leaders-urge-trump-congress-not-to- punish-dreamers-with-deportations-201928/ CHRISTIANITY TODAY (Stetzer Op-Ed): DACA Done Right: A Moment We All Can Stand with DREAMers By Ed Stetzer Sept. 5, 2017 http://www.christianitytoday.com/edstetzer/2017/september/daca-trump-obama-congress- evangelicals.html CHARISMA NEWS: Evangelical Leaders Plead Administration for Swift Action Following DACA Termination Sept. -

April 25, 1990 90-37

NAIivnmw -. ..- SSExsoulive Comminr 801 Commerce #7' Nashville, Tonnesass 372( (615) 244-23 &In C. Shaokleford, Direct Dan Marlin. News Ed\' Maw Knox. Feature €dlc BUREAUS ATLANTA Jim Newton, Chiel. 1350 Spring St.. N.W, Atlanta, Ga. m67, Telephone (401) 873-4011 DALLAS Thomas J. Brannon, Chis( 51 1 N. Akard. Dallaa Texas 75201. Telephone (214) 720-0550 NASHVILLE (8*pNst Sunday School Board) Lloyd T, HwsehoMer. Chiel. 127 Ninth Am. N.. Nashville, fenn. 37234 Telephone 1675) 251-23W RICHMOND (Foreign) Robert L Stanley, Chiel. 3806 Monumanl Ave., Richmond, Va. 23230, Telephom (W)353-0151 WASH1NGtON 200 Mayland AmN.E, Warhirrgton, D.C. W,Tel8phone @02) 544-4226 April 25, 1990 90-37 Executive Committee, board nominees are recommended NASHVILLE (BP)--People to serve on the Southern Baptist Convention Executive Committee and the four denominational boards -- Foreign Mission Board, Home Mission Board, Sunday School Board and Annuity Board -- have been nominated by the 1990 Committee on Nominations. To serve, the nominees must be elected by messengers to the 1990 annual meeting of the SBC, scheduled June 12-14 in the Louisiana Superdome in New Orleans. Three of the boards -+ Foreign, Home and Sunday School -- each received an additional member from Texas. The Baptist General Convention of Texas moved past the 2.5 million member level, entitling it to 10 representatives on the boards. The Annuity Board received an addition member frorn New York. The Baptist Convention of I New York moved past the 25,000 member level, thus entitling it to representation an the Annuity Board and the commissions and institutions of the convention. -

Johnny Hunt Papers Ar

1 JOHNNY HUNT PAPERS AR 914 SBC President Johnny Hunt gives the president’s address at the SBC annual meeting, June 15, 2010, in Orlando, Florida Southern Baptist Historical Library and Archives September, 2015 2 JOHNNY HUNT PAPERS AR 914 Summary Main Entry: Johnny M. Hunt Papers Date Span: 2008 – 2010 Abstract: Southern Baptist minister and denominational leader. Hunt served as president of Southern Baptist Convention (SBC) from 2008 to 2010. The collection contains correspondence and subject files related to his tenure as president of the Southern Baptist Convention. The papers include opinions and questions concerning issues such as abortion, the Great Commission Resurgence Task Force (GCRTF), the King James Version of the Bible, young pastors, and agencies of the Convention, including the International Mission Board and Woman’s Missionary Union. The collection also includes sermons Hunt delivered at his church during his tenure as president of the SBC. Size: 3 linear ft. (6 document boxes) Collection #: AR 914 Biographical Sketch Southern Baptist minister and denominational leader Johnny Hunt was born July 17, 1952, in Lumberton, North Carolina. He is a member of the Lumbee Native American Indian tribe based in North Carolina. He earned a B.A. in religion from Gardner-Webb College (1979) and M.Div. from Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary (SEBTS) (1981). In 1997, SEBTS named the Chair of Church Growth in Johnny Hunt’s honor. He married Janet Allen Hunt, and the couple has two daughters and several grandchildren. Hunt has served as pastor of Lavonia Baptist Church in Mooresboro, North Carolina (1976 – 1979), Falls Baptist Church in Wake Forest, North Carolina (1979 – 1980), Longleaf Baptist Church in Wilmington, North Carolina (1981 – 1986), and First Baptist Church, Woodstock, Georgia (1986 –).