(Mis)Understanding the Cossack Icon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memory, Identity, and the Challenge of Community Among Ukrainians in the Sudbury Region, 1901-1939

Memory, Identity, and the Challenge of Community Among Ukrainians in the Sudbury Region, 1901-1939 by Stacey Raeanna Zembrzycki, B.A., M.A. A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario 27 June 2007 © Stacey Raeanna Zembrzycki, 2007 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Library and Bibliotheque et Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-33519-2 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-33519-2 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce,Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve,sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet,distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform,et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. -

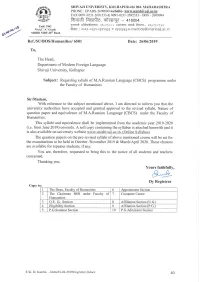

M.A. Russian 2019

************ B+ Accredited By NAAC Syllabus For Master of Arts (Part I and II) (Subject to the modifications to be made from time to time) Syllabus to be implemented from June 2019 onwards. 2 Shivaji University, Kolhapur Revised Syllabus For Master of Arts 1. TITLE : M.A. in Russian Language under the Faculty of Arts 2. YEAR OF IMPLEMENTATION: New Syllabus will be implemented from the academic year 2019-20 i.e. June 2019 onwards. 3. PREAMBLE:- 4. GENERAL OBJECTIVES OF THE COURSE: 1) To arrive at a high level competence in written and oral language skills. 2) To instill in the learner a critical appreciation of literary works. 3) To give the learners a wide spectrum of both theoretical and applied knowledge to equip them for professional exigencies. 4) To foster an intercultural dialogue by making the learner aware of both the source and the target culture. 5) To develop scientific thinking in the learners and prepare them for research. 6) To encourage an interdisciplinary approach for cross-pollination of ideas. 5. DURATION • The course shall be a full time course. • The duration of course shall be of Two years i.e. Four Semesters. 6. PATTERN:- Pattern of Examination will be Semester (Credit System). 7. FEE STRUCTURE:- (as applicable to regular course) i) Entrance Examination Fee (If applicable)- Rs -------------- (Not refundable) ii) Course Fee- Particulars Rupees Tuition Fee Rs. Laboratory Fee Rs. Semester fee- Per Total Rs. student Other fee will be applicable as per University rules/norms. 8. IMPLEMENTATION OF FEE STRUCTURE:- For Part I - From academic year 2019 onwards. -

The Annals of UVAN, Vol . V-VI, 1957, No. 4 (18)

THE ANNALS of the UKRAINIAN ACADEMY of Arts and Sciences in the U. S. V o l . V-VI 1957 No. 4 (18) -1, 2 (19-20) Special Issue A SURVEY OF UKRAINIAN HISTORIOGRAPHY by Dmytro Doroshenko Ukrainian Historiography 1917-1956 by Olexander Ohloblyn Published by THE UKRAINIAN ACADEMY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES IN THE U.S., Inc. New York 1957 EDITORIAL COMMITTEE DMITRY CIZEVSKY Heidelberg University OLEKSANDER GRANOVSKY University of Minnesota ROMAN SMAL STOCKI Marquette University VOLODYMYR P. TIM OSHENKO Stanford University EDITOR MICHAEL VETUKHIV Columbia University The Annals of the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the U. S. are published quarterly by the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the U.S., Inc. A Special issue will take place of 2 issues. All correspondence, orders, and remittances should be sent to The Annals of the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the U. S. ПУ2 W est 26th Street, New York 10, N . Y. PRICE OF THIS ISSUE: $6.00 ANNUAL SUBSCRIPTION PRICE: $6.00 A special rate is offered to libraries and graduate and undergraduate students in the fields of Slavic studies. Copyright 1957, by the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the U.S.} Inc. THE ANNALS OF THE UKRAINIAN ACADEMY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES IN THE U.S., INC. S p e c i a l I s s u e CONTENTS Page P r e f a c e .......................................................................................... 9 A SURVEY OF UKRAINIAN HISTORIOGRAPHY by Dmytro Doroshenko In tr o d u c tio n ...............................................................................13 Ukrainian Chronicles; Chronicles from XI-XIII Centuries 21 “Lithuanian” or West Rus’ C h ro n ic le s................................31 Synodyky or Pom yannyky..........................................................34 National Movement in XVI-XVII Centuries and the Revival of Historical Tradition in Literature ......................... -

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List Denotes new titles recently added to the list while the severity of her older sister's injuries Abuse and the urging of her younger sister, their uncle, and a friend tempt her to testify against Anderson, Laurie Halse him, her mother and other well-meaning Speak adults persuade her to claim responsibility. A traumatic event in the (Mature) (2007) summer has a devastating effect on Melinda's freshman Flinn, Alexandra year of high school. (2002) Breathing Underwater Sent to counseling for hitting his Avasthi, Swati girlfriend, Caitlin, and ordered to Split keep a journal, A teenaged boy thrown out of his 16-year-old Nick examines his controlling house by his abusive father goes behavior and anger and describes living with to live with his older brother, his abusive father. (2001) who ran away from home years earlier under similar circumstances. (Summary McCormick, Patricia from Follett Destiny, November 2010). Sold Thirteen-year-old Lakshmi Draper, Sharon leaves her poor mountain Forged by Fire home in Nepal thinking that Teenaged Gerald, who has she is to work in the city as a spent years protecting his maid only to find that she has fragile half-sister from their been sold into the sex slave trade in India and abusive father, faces the that there is no hope of escape. (2006) prospect of one final confrontation before the problem can be solved. McMurchy-Barber, Gina Free as a Bird Erskine, Kathryn Eight-year-old Ruby Jean Sharp, Quaking born with Down syndrome, is In a Pennsylvania town where anti- placed in Woodlands School in war sentiments are treated with New Westminster, British contempt and violence, Matt, a Columbia, after the death of her grandmother fourteen-year-old girl living with a Quaker who took care of her, and she learns to family, deals with the demons of her past as survive every kind of abuse before she is she battles bullies of the present, eventually placed in a program designed to help her live learning to trust in others as well as her. -

In the Lands of the Romanovs: an Annotated Bibliography of First-Hand English-Language Accounts of the Russian Empire

ANTHONY CROSS In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of The Russian Empire (1613-1917) OpenBook Publishers To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/268 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917) Anthony Cross http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2014 Anthony Cross The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt it and to make commercial use of it providing that attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that he endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Cross, Anthony, In the Land of the Romanovs: An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917), Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/ OBP.0042 Please see the list of illustrations for attribution relating to individual images. Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omissions or errors will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. As for the rights of the images from Wikimedia Commons, please refer to the Wikimedia website (for each image, the link to the relevant page can be found in the list of illustrations). -

Another History of Europe at War. Gendarmeries and Police Facing the First World War (1914-1918)

Another history of Europe at war. Gendarmeries and police facing the First World War (1914-1918) International Conference organised at the EOGN in Melun on the 4th , 5th and 6th February 2016 by : Le Centre de recherche de l'École des officiers de la Gendarmerie nationale and Le musée de la Gendarmerie, in cooperation with : Université Paris-Sorbonne the Centre d'histoire du XIXe siècle Labex EHNE Université catholique de Louvain-la-Neuve Le Pôle d'attraction interuniversitaire « Justice et populations : l'expérience belge en perspective internationale ») Dr. Guillaume Payen Chef du pôle histoire et faits sociaux contemporains du CREOGN, chercheur associé au Centre Roland Mousnier, université Paris-Sorbonne Dr. Jonas Campion Chargé de recherches du FRS-FNRS, Centre d’histoire du droit et de la justice, université catholique de Louvain-la-Neuve (Belgique) Dr. Laurent López Chercheur associé au CESDIP (université de Versailles/Saint Quentin) et au Centre d'histoire du XIXe siècle (universités Panthéon-Sorbonne et Paris-Sorbonne) The history of Europe into the First World War is still to be written from the police's point of view, in spite of the frequent claim of "constraint"1 in the conflict's historiography. Classically marking the break between the 19th and the 20th centuries, the First World War is more than a separation between two periods. It is a deep historiographic void on both national and European scales. From a Europe-wide perspective, while the comparative approach carried out by Jonas Campion and confronting the cases of the Belgian, French and Dutch gendarmeries focuses on the end of the Second World War2, the book published under G. -

Socialist Realism Seen in Maxim Gorky's Play The

SOCIALIST REALISM SEEN IN MAXIM GORKY’S PLAY THE LOWER DEPTHS AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By AINUL LISA Student Number: 014214114 ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAMME DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2009 SOCIALIST REALISM SEEN IN MAXIM GORKY’S PLAY THE LOWER DEPTHS AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By AINUL LISA Student Number: 014214114 ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAMME DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2009 i ii iii HHaappppiinneessss aallwwaayyss llooookkss ssmmaallll wwhhiillee yyoouu hhoolldd iitt iinn yyoouurr hhaannddss,, bbuutt lleett iitt ggoo,, aanndd yyoouu lleeaarrnn aatt oonnccee hhooww bbiigg aanndd pprreecciioouuss iitt iiss.. (Maxiim Gorky) iv Thiis Undergraduatte Thesiis iis dediicatted tto:: My Dear Mom and Dad,, My Belloved Brotther and Siistters.. v vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Firstly, I would like to praise Allah SWT for the blessings during the long process of this undergraduate thesis writing. I would also like to thank my patient and supportive father and mother for upholding me, giving me adequate facilities all through my study, and encouragement during the writing of this undergraduate thesis, my brother and sisters, who are always there to listen to all of my problems. I am very grateful to my advisor Gabriel Fajar Sasmita Aji, S.S., M.Hum. for helping me doing my undergraduate thesis with his advice, guidance, and patience during the writing of my undergraduate thesis. My gratitude also goes to my co-advisor Dewi Widyastuti, S.Pd., M.Hum. -

PDF File, 139.89 KB

Armed Forces Equivalent Ranks Order Men Women Royal New Zealand New Zealand Army Royal New Zealand New Zealand Naval New Zealand Royal New Zealand Navy: Women’s Air Force: Forces Army Air Force Royal New Zealand New Zealand Royal Women’s Auxilliary Naval Service Women’s Royal New Zealand Air Force Army Corps Nursing Corps Officers Officers Officers Officers Officers Officers Officers Vice-Admiral Lieutenant-General Air Marshal No equivalent No equivalent No equivalent No equivalent Rear-Admiral Major-General Air Vice-Marshal No equivalent No equivalent No equivalent No equivalent Commodore, 1st and Brigadier Air Commodore No equivalent No equivalent No equivalent No equivalent 2nd Class Captain Colonel Group Captain Superintendent Colonel Matron-in-Chief Group Officer Commander Lieutenant-Colonel Wing Commander Chief Officer Lieutenant-Colonel Principal Matron Wing Officer Lieutentant- Major Squadron Leader First Officer Major Matron Squadron Officer Commander Lieutenant Captain Flight Lieutenant Second Officer Captain Charge Sister Flight Officer Sub-Lieutenant Lieutenant Flying Officer Third Officer Lieutenant Sister Section Officer Senior Commis- sioned Officer Lieutenant Flying Officer Third Officer Lieutenant Sister Section Officer (Branch List) { { Pilot Officer Acting Pilot Officer Probationary Assistant Section Acting Sub-Lieuten- 2nd Lieutenant but junior to Third Officer 2nd Lieutenant No equivalent Officer ant Navy and Army { ranks) Commissioned Officer No equivalent No equivalent No equivalent No equivalent No equivalent No -

Contours and Consequences of the Lexical Divide in Ukrainian

Geoffrey Hull and Halyna Koscharsky1 Contours and Consequences of the Lexical Divide in Ukrainian When compared with its two large neighbours, Russian and Polish, the Ukrainian language presents a picture of striking internal variation. Not only are Ukrainian dialects more mutually divergent than those of Polish or of territorially more widespread Russian,2 but on the literary level the language has long been characterized by the existence of two variants of the standard which have never been perfectly harmonized, in spite of the efforts of nationalist writers for a century and a half. While Ukraine’s modern standard language is based on the eastern dialect of the Kyiv-Poltava-Kharkiv triangle, the literary Ukrainian cultivated by most of the diaspora communities continues to follow to a greater or lesser degree the norms of the Lviv koiné in 1 The authors would like to thank Dr Lance Eccles of Macquarie University for technical assistance in producing this paper. 2 De Bray (1969: 30-35) identifies three main groups of Russian dialects, but the differences are the result of internal evolutionary divergence rather than of external influences. The popular perception is that Russian has minimal dialectal variation compared with other major European languages. Maximilian Fourman (1943: viii), for instance, told students of Russian that the language ‘is amazingly uniform; the same language is spoken over the vast extent of the globe where the flag of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics flies; and you will be understood whether you are speaking to a peasant or a university professor. There are no dialects to bother you, although, of course, there are parts of the Soviet Union where Russian may be spoken rather differently, as, for instance, English is spoken differently by a Londoner, a Scot, a Welshman, an Irishman, or natives of Yorkshire or Cornwall. -

Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc

Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc. 7407 La Jolla Boulevard www.raremaps.com (858) 551-8500 La Jolla, CA 92037 [email protected] La Journee De Poltawa En Ukraine le 8e. julliet 1709; Entre l'Armee de sa Majeste Suedoise Charles XII, et celle de sa Majeste Csarienne Pierre I, Empereur de la grande Russie . 1714 Stock#: 29171 Map Maker: de Fer Date: 1714 Place: Paris Color: Hand Colored Condition: VG Size: 13.5 x 9 inches Price: SOLD Description: Detailed plan of the Battle of Poltava. The Battle of Poltava fought on June 27-28, 1709 was the decisive victory of Peter I of Russia over Charles XII of Sweden in the most famous of the battles of the Great Northern War. While the date given on the map reflects a July 8, 1709 battle, the modern date is given as June 27-28. After the Battle of Narva in 1700, Czar Peter I was reorganized his army, while Charles XII of Sweden fought for 6 years against Augustus II of Saxony-Poland. Peter first offensive move with his reorganized Russian Army was to establish the city of Saint Petersburg in Swedish territory. Charles attacked the Russian heartland with the intent on an assault on Moscow from Poland. The Swedish army of almost 44,000 men left Saxony on August 22, 1707 and marched eastwards. When they reached the Vistula River and crossed on December 30, then continued through Masuria and took Grodno on January 28, 1708. The Swedes continued to the area around Smorgon and Minsk ,where the army went into winter quarters. -

Jewish Cemetries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine

Syracuse University SURFACE Religion College of Arts and Sciences 2005 Jewish Cemetries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine Samuel D. Gruber United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/rel Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Gruber, Samuel D., "Jewish Cemeteries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine" (2005). Full list of publications from School of Architecture. Paper 94. http://surface.syr.edu/arc/94 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts and Sciences at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religion by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JEWISH CEMETERIES, SYNAGOGUES, AND MASS GRAVE SITES IN UKRAINE United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad 2005 UNITED STATES COMMISSION FOR THE PRESERVATION OF AMERICA’S HERITAGE ABROAD Warren L. Miller, Chairman McLean, VA Members: Ned Bandler August B. Pust Bridgewater, CT Euclid, OH Chaskel Besser Menno Ratzker New York, NY Monsey, NY Amy S. Epstein Harriet Rotter Pinellas Park, FL Bingham Farms, MI Edgar Gluck Lee Seeman Brooklyn, NY Great Neck, NY Phyllis Kaminsky Steven E. Some Potomac, MD Princeton, NJ Zvi Kestenbaum Irving Stolberg Brooklyn, NY New Haven, CT Daniel Lapin Ari Storch Mercer Island, WA Potomac, MD Gary J. Lavine Staff: Fayetteville, NY Jeffrey L. Farrow Michael B. Levy Executive Director Washington, DC Samuel Gruber Rachmiel -

NARRATING the NATIONAL FUTURE: the COSSACKS in UKRAINIAN and RUSSIAN ROMANTIC LITERATURE by ANNA KOVALCHUK a DISSERTATION Prese

NARRATING THE NATIONAL FUTURE: THE COSSACKS IN UKRAINIAN AND RUSSIAN ROMANTIC LITERATURE by ANNA KOVALCHUK A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of Comparative Literature and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2017 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Anna Kovalchuk Title: Narrating the National Future: The Cossacks in Ukrainian and Russian Romantic Literature This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of Comparative Literature by: Katya Hokanson Chairperson Michael Allan Core Member Serhii Plokhii Core Member Jenifer Presto Core Member Julie Hessler Institutional Representative and Scott L. Pratt Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2017 ii © 2017 Anna Kovalchuk iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Anna Kovalchuk Doctor of Philosophy Department of Comparative Literature June 2017 Title: Narrating the National Future: The Cossacks in Ukrainian and Russian Romantic Literature This dissertation investigates nineteenth-century narrative representations of the Cossacks—multi-ethnic warrior communities from the historical borderlands of empire, known for military strength, pillage, and revelry—as contested historical figures in modern identity politics. Rather than projecting today’s political borders into the past and proceeding from the claim that the Cossacks are either Russian or Ukrainian, this comparative project analyzes the nineteenth-century narratives that transform pre- national Cossack history into national patrimony. Following the Romantic era debates about national identity in the Russian empire, during which the Cossacks become part of both Ukrainian and Russian national self-definition, this dissertation focuses on the role of historical narrative in these burgeoning political projects.